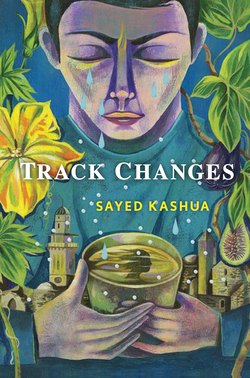

Читать книгу Track Changes - Sayed Kashua - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

Оглавление“What’s your earliest memory?”

That was the question I asked interviewees as soon as I hit the red Record button on the recorder.

What’s my earliest memory? Sometimes I ask myself, too.

I remember my mother waking me up in the middle of the night, frightened and stressed, hoisting me onto her shoulders. And I remember insisting on taking my new box of crayons with me, stretching my hand out toward the place under my pillow where I’d hidden them, but I couldn’t reach. We’ve got to hurry. The buses are heading out soon, and we must drive my grandmother to the center of the village, to the square outside the old Bank Hapoalim, where we’ll wave goodbye to her and the others as they set out on the haj, the first group to be granted exit visas to Mecca.

Or maybe it’s a memory of my back pressed against the low wall that surrounded the first kindergarten in Tira, in a part of the neighborhood far from my home, which my parents decided to send me to because of their jobs. I’m leaning against the wall and staring at some kids playing with metal toy cars with small seats and squeaky steering wheels that can spin endlessly in either direction. Close to me are seesaws in the shape of a horse and a plane, and a sandbox. I look at the other kids and cry, waiting for the moment when my parents will come and get me and failing to understand why the other kids are not, like me, standing with their backs to the wall and wailing until their parents arrive. Slowly I discover that the kindergarten teacher is standing beside me, looking over the wall. It takes me some time to realize that she is talking about me when she says, “He’s always like this. He doesn’t play or listen to stories or speak to any of the other kids.” And I look back and see that she is talking to my father, who is standing right behind me on the other side of the white brick wall. I turn to look at him and he smiles at me, tousles my hair, and waves the gray handkerchief that we are all required to carry. “You forgot this,” he says and smiles at me.

I have no doubt that both of these events took place. I don’t know which came first but I regurgitate them often. I don’t have a lot of childhood memories other than those two, and I haven’t been able to bring up new ones, aside from those that have been carved into the walls of my mind, in a spot where the beam of my memory repeatedly falls. Those things happened; I will not even entertain the notion that they did not, even though it is unclear to me how it is that I see myself in both of those distant memories. How is it that I see the kid crying rather than being there myself, my back against the wall; how is it that I watch the kid with the leaping heart see his father, a kid that is no longer me?

Soon, when we get close to Tira, I’ll smell the trees, the clouds, the strawberries, and the figs that I used to pick with my father, even though it is not fig season and the place where the trees once stood is now home to a row of exhaust pipe garages.