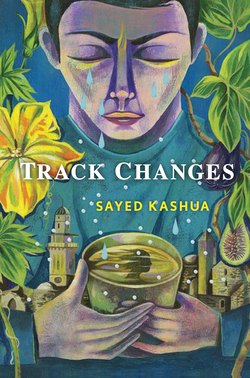

Читать книгу Track Changes - Sayed Kashua - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

ОглавлениеWhenever people ask me: “What are you doing in Illinois?” I always say that I’m writing a book, even though ever since we’ve arrived I’ve not written a single word.

To be honest, I’ve only been asked this a few times, mostly at social events held by the department where my wife is teaching, events that family and spouses are specifically invited to and that she, having told her colleagues that she’s married, was compelled to request I accompany her to, knowing full well that I would not pass on an opportunity to feel like we were in a relationship.

“So, you’re a writer?”

I lie because I have nothing better to say.

Albeit I’ve written thirty books but only as a hired hand. Aside from one short story, less than a page long and featured in the Hebrew University students’ journal some fifteen years ago, I’ve not published a single piece of writing under my own name, and even then the editor misspelled my first name, adding a guttural vowel where there was none.

Sometimes I think about my book, the one I promised I would never write, and I imagine the protagonist in a furnished one-room apartment in the University of Illinois dorms.

Around here they only count bedrooms when specifying the number of rooms in an apartment. He lives alone, this protagonist, in the married-student dorms. He has a small bedroom, in the middle of which sits a queen-size bed on an appropriately sized box mattress, with no headboard. He has a closet, which is nothing more than an accordion-like door that opens to a narrow, carpeted, shelf-less space that houses a single hanging bar, fixed at the protagonist’s eye level, five foot seven.

In his apartment there’s also a living room and a three-seater couch, an old TV with cable access, and a desk made out of sturdy wood. In that same open space there is also a small kitchen and a refrigerator, a stove and an electric stovetop, a microwave and a coffee machine. It was all there when I moved in; I bought no new furniture aside from some plastic shelves that I got at one of the giant hardware stores, a translucent set of storage drawers that are bought individually and can be assembled any which way, like Lego. I placed them one on top of another and shoved them into my bedroom closet. The bottom one is for socks, the top for underwear.

That’s where I wake up almost every morning. That’s where I have my first coffee and my first cigarette.

I brush my teeth, wash my face, dress, and wait to leave the house. Usually I click through the Hebrew and Arabic Israeli news sites, and sometimes I flip on the TV and passively watch the local news or the Weather Channel. It is during those mornings, from the moment I open my eyes until the moment I leave the house, that I am assailed by the sharpest pangs of longing for Palestine.

At six thirty I head out to the bus stop near the dorms. Usually I am the first passenger on the bus. I nod at the driver, whom I see almost every day, and sometimes she nods back. Off campus more passengers board—mostly gas station attendants and salespeople coming off night shifts at one of the twenty-four-hour stores. There are no college kids on the buses at that time of day and no students on their way to school.

At a quarter to seven I reach the house. I have a key and don’t have to ring the bell or ask my wife’s permission to enter. She’s already awake, seated at the kitchen table with her coffee. Palestine drinks cappuccinos. She told me she once used to cook coffee in a pot over an open flame. When she left Tira, she turned to instant coffee, and once we could afford it she bought herself a coffee machine.

My arrival is a sign that it’s time to wake the boys. Palestine no longer asks if I’d like coffee. I take my shoes off by the door, shed my winter layers, and take the wooden steps, padded with a gray American carpet, to the bedroom level. The two boys share a single room with matching beds and a desk for the eldest, who is ten. He’s the one I wake first. I stroke his hair, say good morning, give him a kiss. He gets up quickly, says good morning, and gets to his feet, ready to wash his face, brush his teeth, and get dressed. Then I sit on the edge of my younger son’s bed, stroke his hair, kiss his cheeks, whisper gentle words in a soft voice. He refuses to rise. He doesn’t like going to kindergarten. Two years have passed and the first words out of his mouth every single day are: “I don’t want to go to school.” At first he said that sentence in Hebrew, but after three months in the United States he started to protest in English. The door to my daughter’s room, when she’s at home, is perpetually locked. She wakes up alone, wishes no one a good morning, and responds to no one when she is greeted but is always ready on time.

I head over to the garage through a side door connected to the kitchen, open the door by pressing a button, raising it a couple of feet off the ground so that the exhaust fumes don’t gather inside, and start the car so that it warms up, at least slightly, while the boys slurp down the last of their cereal. Then they struggle with their shoes.