Читать книгу Discovering Japanese Handplanes - Scott Wynn - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

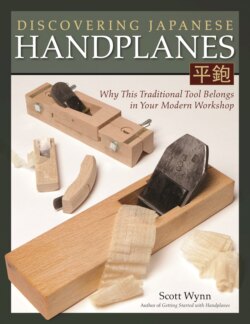

The Dai

ОглавлениеThe block of wood that holds the blade—it’s a single block, not a laminate—is called the dai. It’s a very dense oak, called kashi either white or red, though one reliable source (only one) says it is a type of cherry; perhaps this discrepancy may be due to a confusion over scientific names. White kashi is generally preferred as it tends to be denser and heavier, but I have experienced pieces of red kashi dai that were far denser than almost any wood I’ve worked; my chisel almost bounced off one piece I worked with. The trees are 40 to 70 years old and are felled between late December and early March; trunk diameters are from 30cm to 50cm. Until the 1920s the blanks for the dai were split, giving material that last better and is resistant to warping, but now it is all sawn to size. The dai-maker buys his blanks from the sawmill and stores them for two to three years before fitting blades to them. Incidentally, the dai-maker has no part in the production of the blade or chipbreaker; that is another trade. He merely fits them individually to the block.

Figure 1-4. How to Hold the Plane The Japanese-style plane is normally pulled in use, though it can, of course be pushed, and the smaller planes are surprisingly comfortable when used like this. I sometimes push the plane on the jobsite when holding is awkward and I have to remove a lot of wood. Here, a Japanese-style compass plane, its sole shaped to a gentle curve, smoothes the sweep of a bench seat.

The whole concept of the Japanese plane with its wedge shaped blade is based on the resiliency of the wood block that holds it. The wood must not give too much as this may result in blade chatter or the blade losing its adjustment. But it must give some—just the right amount—or the blade would not be adjustable. If you’re making your own planes, finding a substitute for the woods traditionally used in Japan is tricky.

The plane is meant to be pulled rather than pushed (see Figure 1-4), and the Japanese apparently are virtually the only woodworking culture where this is true. Many woodworking traditions have a few pulled tools, but not even their Asian neighbors, from whence their tools were derived, have major planes that are pulled. This may have evolved because the majority of Japanese craftsmen sit while they work, the cabinetmakers and furniture makers using an inclined planing board set on the floor. The board has a stop on the near end and slopes toward the user, allowing an efficient, ergonomic movement. On a wide piece, the work is shifted along the stop with the foot in between strokes of the plane. (See The Workbench Book by Scott Landis, Taunton Press, 1987, for more details on Japanese benches and working style.)