Читать книгу Discovering Japanese Handplanes - Scott Wynn - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 ANATOMY OF THE JAPANESE PLANE The Blade

ОглавлениеThe blade is the heart of a Japanese plane; in contrast to a Western plane, often a complex and weighty construct of machined metal where the cost of the body is 10 times the cost of the blade or more, in a Japanese plane the blade may be 10 times the cost of the body, and sometimes much more. Traditionally, the blade is forge laminated and, on any plane of quality, hand-forged. This is something you will not find on a contemporary Western plane of any quality. The hand-forged blade is what sets the Japanese plane above its overelaborate competitors. Its production is the result of nearly 1,000 years of metallurgical tradition. Much of the Japanese plane’s ability to cut cleanly comes from this singular ability of the blade to get incredibly sharp, and to shear without tearing. This blade, at an appropriate angle and combined with a fine throat and/or a well-set chipbreaker, will smooth the most difficult of woods.

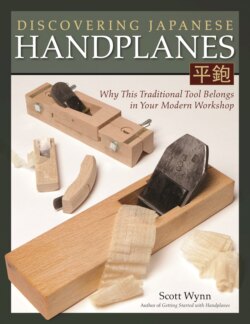

Japanese-Style Smoothing Planes.

Only two components constitute a complete plane: the blade and the wood block that holds it. Or four if you add a chipbreaker and its retaining pin. The plane’s conceptual simplicity, however, belies its great sophistication and structural refinement. The blade itself is thick and wedge shaped and fits into a precisely cut escapement in that block of wood. (Contrary to a popular misconception, except in the occasional specialty plane and some new, modern variations, the chipbreaker is not traditionally used to wedge the blade into position.) However, many nuances to the shape of the blade and details of the block that are not readily apparent must be attended to when setting up the plane. Besides the blade being wedge-shaped, the top face of the blade (the side opposite the bevel) is hollow ground. Much of this hollow is formed at the forge, so not much steel is removed when the blacksmith finishes it on the grinder. This hollow makes flattening the back of the blade easier, something that all blades (not just Japanese blades) must have done to them when they are first sharpened. I am always thankful the hollow is there because the steel of the laminated blade is so hard.

Figure 1-1 Japanese-Style Smooth Plane This blade has harder pieces of steel inlaid into the top and corners to reduce mushrooming from being adjusted with a hammer; Independent chipbreaker; Tapered blade wedges into custom-fit bed and abutments; Cross pin to wedge chipbreaker

Figure 1-2. The traditional Japanese blade is always laminated with hard edge steel and softer backing steel. If you look closely at the backing steel here, you can see some layering and variations that reveal its handworked origins.

The blade is also concave along its length on the bottom (bed side) and the plane bed must be made convex and fitted to this bevel side of the blade (and since most blades are virtually handmade, this is a custom fitting). This shaping of the blade and body is done to reduce lateral shifting of the blade during use.

The blade is also tapered across its width, being slightly narrower at the edge than at the top. This is to allow room for lateral adjustment, while still maintaining a good grip on the blade.

The blade angle most commonly available is about 40°, or more accurately 8 in 10 (the Japanese use a rise and run based on 10 rather than degrees. This explains some of the odd degree settings sometimes encountered.) Some suppliers will have planes with 47.5° (11 in 10). On rare occasion you might encounter 43° (9 in 10). The Japanese believe a really sharp blade is more effective than use of higher blade angles, though mainly I think it’s because the vast majority of their market works softer woods. The advent of 47.5° blade angle was largely a result of one of the American suppliers requesting it from the maker for his American market. I also think the Japanese woodworker does not hesitate to make his own planes at whatever angle he thinks he needs; up until the 1930s all craftsmen made their own planes, buying the blade and the block separately.

While recently some planes have been made available with alloy and even high speed steel blades, often aimed at the less experienced or the home owner, and there have been some experiments with hi speed steel for use in difficult woods, the vast majority of blades you will encounter will be basically fine-grain carbon steel. The two most common types are what are called white steel and blue steel (or white paper steel and blue paper steel). They derive their name from the color of the identifying paper label applied by the steel maker (usually Hitachi). Both have carbon in the 1% to 1.4% range with .1% to .2% silica and 0.2% to 0.3% manganese. Blue paper steels technically are alloy steels with .2% to .5% chromium and 1% to 1.5% tungsten, with up to 2.25% tungsten in the super blue steel.