Читать книгу Discovering Japanese Handplanes - Scott Wynn - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

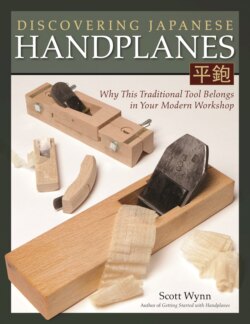

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеI began woodworking in the late 1960s, a move to be expected, I suppose, because I was raised in a family of cabinetmakers, patternmakers, turners, gunsmiths, and house builders. I felt it was a logical extension of the hands-on building design work I was doing at the time. I picked up what tools I could from the local hardware store and what tips I could from my relatives and a few scattered, scarce written sources. The tools available at that time were immediately disappointing. These were not the tools that built the works of art in the museums. Certainly over the course of 3,000 or more years of woodworking, our predecessors, who did all of their work by hand, had developed effective ways to maximize their efforts to produce flawless work. The hand tools available to me at that time were not capable of flawless work by any means, and what they could do took backbreaking, hand-blistering effort.

I began to look further afield, searching the available sources. In the early 1970s, I drove across the country from my home in Ohio to Berkeley, Calif., to search out an obscure Japanese-tool dealer to look at what were then exotic tools. (The drawings of them in the Whole Earth Catalog looked too bizarre to be real!) Those tools were a revelation—and a validation. Japanese tools were meant to be used, used hard, and to produce rapid, excellent results. Well-made hand tools could be a joy to use and be highly productive! I began experimenting with any I could get my hands on, identifying strengths and weaknesses, and the work for which were best suited. Moreover, I used them daily to make my living.

Clearly, I was not alone in my frustration with the quality and availability of Western tools during the rebirth of woodworking that began in the late 1970s. At that time in the San Francisco Bay Area there were a number of highly skilled craftsmen formally trained in Japan doing work and training scores of woodworkers in Japanese carpentry and the care and use of Japanese tools. The woodworking community shared this knowledge back and forth, bolstered by demonstrations of visiting craftsmen that were promoted by Japanese manufacturers and the two importers of Japanese hand tools in the Bay Area. This tradition continues today.

There has since been a resurge in the quality of Western hand tools, planes in particular. These tools are more familiar to us and now are capable of producing better work than in previous decades. In addition, James Krenov was one of those who spearheaded the woodworking revival, and his handmade planes have a great allure. Norris-style planes were rediscovered; who could resist the beautiful combinations of steel, brass, and exotic hardwoods? But none of these planes have the blades. The blades are nearly an afterthought; they’re like an excuse to build an elaborate, expensive mechanism. You can spend a week’s salary on a Norris reproduction and the blade you get is cut from common flat stock; and the chipbreaker, un-hardened and not for hard use, is used more to attach the adjuster. And the elaborate mechanism is just that: elaborate, often awkward, sometimes ungainly. Or, if you’re interested in productivity, you might say—slow—and expensive. Are these forms just a result of marketing? We all are attracted to the handsome pieces of machinery these tools are, but many of us use them so little we can’t tell the difference in the performance of the blades, so why bother, perhaps the manufacturers are asking, to put the extra time and effort into a better blade?

If you use your planes a lot and you expect them to perform, take a look at Japanese planes.

Japanese planes are a delight to use. They are fast, efficient, effective. They sit low on the work giving great feedback and a relaxed stability. Despite the clean, lean geometric, almost modernist aesthetic of the block and blade, they accommodate the hands quite well and in a multitude of planing positions, and are quite comfortable to use for long periods. And of course the blade: individually worked to achieve a balance of resilient structure, fine grain, and a hardness that maximizes the life of the edge, the blade’s cutting abilities and ease of resharpening.

Additionally, Japanese planes also can be highly effective for shaping work, because they can be easily modified or fabricated in an hour or two for same-day use. They are easy to adjust, and the adjustment is precise. Because the chipbreaker is not attached to the blade, it can be easily adjusted up or down to accommodate a variety of work, or even left off if need be. Also, partially for this reason, the blade removes quickly for re-sharpening and re-installation. Taking the blade out for sharpening requires only a few taps of a hammer; no loosening and tightening of very tight screws or tedious adjustment of the chipbreaker that tends to shift as that screw is tightened. If the blade is not particularly dull, I can knock it out, sharpen, reinstall, and adjust to use in three to four minutes. Taking the blade out, putting it back in, and adjusting it to use—without sharpening it—takes about 45 seconds. And the results from use of the plane can be stunning, as the blades available are arguably the best in the world.

Though the form is very dissimilar to Western planes, Japanese planes use the same anatomical “tactics” to do their work as do the Western planes. In this sense, they are familiar. These tactics are then altered in the same way according to the work the plane is intended to do. Unlike Western planes, however, Japanese planes are elegantly simple in concept, but complex and refined in execution. The basic plane consists of only two pieces: blade and block.

Because of the wedge-fit of the blade, and the independence of the chipbreaker, initial set-up requires instruction and perhaps some patience, but this is true of any plane from which you expect good results. Getting half-decent instruction in how to do this, does greatly speed things up (the intention of this book). I find the plane, being made of wood, does require you to pay attention to it, but otherwise, I find it to be to be surprisingly reliable and once set up, it will perform consistently with only some attention to detail. Storing the plane in a cabinet or drawer with the blade loose when not in use reduces the amount of tuning-up of the dai you may have to do because of temperature and humidity swings.

Some of the information I present here may break from tradition. I have been working with the planes for four decades and have made some adaptations and have experimented to better accommodate Western woods and projects, but the amount of variation from tradition is minimal, and from what I can observe, no different than you might find among individual Japanese craftsmen.