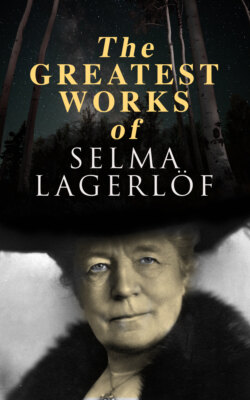

Читать книгу The Greatest Works of Selma Lagerlöf - Selma Lagerlöf - Страница 116

II

ОглавлениеThis is how the old woman came to live in the vine-dresser’s hut. And she conceived a great friendship for the young people. But for all that she never told them whence she had come, or who she was, and they understood that she would not have taken it in good part had they questioned her.

But one evening, when the day’s work was done, and all three sat on the big, flat rock which lay before the entrance, and partook of their evening meal, they saw an old man coming up the path.

He was a tall and powerfully built man, with shoulders as broad as a gladiator’s. His face wore a cheerless and stern expression. The brows jutted far out over the deep-set eyes, and the lines around the mouth expressed bitterness and contempt. He walked with erect bearing and quick movements.

The man wore a simple dress, and the instant the vine-dresser saw him, he said: “He is an old soldier, one who has been discharged from service and is now on his way home.”

When the stranger came directly before them he paused, as if in doubt. The laborer, who knew that the road terminated a short distance beyond the hut, laid down his spoon and called out to him: “Have you gone astray, stranger, since you come hither? Usually, no one takes the trouble to climb up here, unless he has an errand to one of us who live here.”

When he questioned in this manner, the stranger came nearer. “It is as you say,” said he. “I have taken the wrong road, and now I know not whither I shall direct my steps. If you will let me rest here a while, and then tell me which path I shall follow to get to some farm, I shall be grateful to you.”

As he spake he sat down upon one of the stones which lay before the hut. The young woman asked him if he wouldn’t share their supper, but this he declined with a smile. On the other hand it was very evident that he was inclined to talk with them, while they ate. He asked the young folks about their manner of living, and their work, and they answered him frankly and cheerfully.

Suddenly the laborer turned toward the stranger and began to question him. “You see in what a lonely and isolated way we live,” said he. “It must be a year at least since I have talked with any one except shepherds and vineyard laborers. Can not you, who must come from some camp, tell us something about Rome and the Emperor?”

Hardly had the man said this than the young wife noticed that the old woman gave him a warning glance, and made with her hand the sign which means—Have a care what you say.

The stranger, meanwhile, answered very affably: “I understand that you take me for a soldier, which is not untrue, although I have long since left the service. During Tiberius’ reign there has not been much work for us soldiers. Yet he was once a great commander. Those were the days of his good fortune. Now he thinks of nothing except to guard himself against conspiracies. In Rome, every one is talking about how, last week, he let Senator Titius be seized and executed on the merest suspicion.”

“The poor Emperor no longer knows what he does!” exclaimed the young woman; and shook her head in pity and surprise.

“You are perfectly right,” said the stranger, as an expression of the deepest melancholy crossed his countenance. “Tiberius knows that every one hates him, and this is driving him insane.”

“What say you?” the woman retorted. “Why should we hate him? We only deplore the fact that he is no longer the great Emperor he was in the beginning of his reign.”

“You are mistaken,” said the stranger. “Every one hates and detests Tiberius. Why should they do otherwise? He is nothing but a cruel and merciless tyrant. In Rome they think that from now on he will become even more unreasonable than he has been.”

“Has anything happened, then, which will turn him into a worse beast than he is already?” queried the vine-dresser.

When he said this, the wife noticed that the old woman gave him a new warning signal, but so stealthily that he could not see it.

The stranger answered him in a kindly manner, but at the same time a singular smile played about his lips.

“You have heard, perhaps, that until now Tiberius has had a friend in his household on whom he could rely, and who has always told him the truth. All the rest who live in his palace are fortune-hunters and hypocrites, who praise the Emperor’s wicked and cunning acts just as much as his good and admirable ones. But there was, as we have said, one alone who never feared to let him know how his conduct was actually regarded. This person, who was more courageous than senators and generals, was the Emperor’s old nurse, Faustina.”

“I have heard of her,” said the laborer. “I’ve been told that the Emperor has always shown her great friendship.”

“Yes, Tiberius knew how to prize her affection and loyalty. He treated this poor peasant woman, who came from a miserable hut in the Sabine mountains, as his second mother. As long as he stayed in Rome, he let her live in a mansion on the Palatine, that he might always have her near him. None of Rome’s noble matrons has fared better than she. She was borne through the streets in a litter, and her dress was that of an empress. When the Emperor moved to Capri, she had to accompany him, and he bought a country estate for her there, and filled it with slaves and costly furnishings.”

“She has certainly fared well,” said the husband.

Now it was he who kept up the conversation with the stranger. The wife sat silent and observed with surprise the change which had come over the old woman. Since the stranger arrived, she had not spoken a word. She had lost her mild and friendly expression. She had pushed her food aside, and sat erect and rigid against the door-post, and stared straight ahead, with a severe and stony countenance.

“It was the Emperor’s intention that she should have a happy life,” said the stranger. “But, despite all his kindly acts, she too has deserted him.”

The old woman gave a start at these words, but the young one laid her hand quietingly on her arm. Then she began to speak in her soft, sympathetic voice. “I can not believe that Faustina has been as happy at court as you say,” she said, as she turned toward the stranger. “I am sure that she has loved Tiberius as if he had been her own son. I can understand how proud she has been of his noble youth, and I can even understand how it must have grieved her to see him abandon himself in his old age to suspicion and cruelty. She has certainly warned and admonished him every day. It has been terrible for her always to plead in vain. At last she could no longer bear to see him sink lower and lower.”

The stranger, astonished, leaned forward a bit when he heard this; but the young woman did not glance up at him. She kept her eyes lowered, and spoke very calmly and gently.

“Perhaps you are right in what you say of the old woman,” he replied. “Faustina has really not been happy at court. It seems strange, nevertheless, that she has left the Emperor in his old age, when she had endured him the span of a lifetime.”

“What say you?” asked the husband. “Has old Faustina left the Emperor?”

“She has stolen away from Capri without any one’s knowledge,” said the stranger. “She left just as poor as she came. She has not taken one of her treasures with her.”

“And doesn’t the Emperor really know where she has gone?” asked the wife.

“No! No one knows for certain what road the old woman has taken. Still, one takes it for granted that she has sought refuge among her native mountains.”

“And the Emperor does not know, either, why she has gone away?” asked the young woman.

“No, the Emperor knows nothing of this. He can not believe she left him because he once told her that she served him for money and gifts only, like all the rest. She knows, however, that he has never doubted her unselfishness. He has hoped all along that she would return to him voluntarily, for no one knows better than she that he is absolutely without friends.”

“I do not know her,” said the young woman, “but I think I can tell you why she has left the Emperor. The old woman was brought up among these mountains in simplicity and piety, and she has always longed to come back here again. Surely she never would have abandoned the Emperor if he had not insulted her. But I understand that, after this, she feels she has the right to think of herself, since her days are numbered. If I were a poor woman of the mountains, I certainly would have acted as she did. I would have thought that I had done enough when I had served my master during a whole lifetime. I would at last have abandoned luxury and royal favors to give my soul a taste of honor and integrity before it left me for the long journey.”

The stranger glanced with a deep and tender sadness at the young woman. “You do not consider that the Emperor’s propensities will become worse than ever. Now there is no one who can calm him when suspicion and misanthropy take possession of him. Think of this,” he continued, as his melancholy gaze penetrated deeply into the eyes of the young woman, “in all the world there is no one now whom he does not hate; no one whom he does not despise—no one!”

As he uttered these words of bitter despair, the old woman made a sudden movement and turned toward him, but the young woman looked him straight in the eyes and answered: “Tiberius knows that Faustina will come back to him whenever he wishes it. But first she must know that her old eyes need never more behold vice and infamy at his court.”

They had all risen during this speech; but the vine-dresser and his wife placed themselves in front of the old woman, as if to shield her.

The stranger did not utter another syllable, but regarded the old woman with a questioning glance. Is this your last word also? he seemed to want to say. The old woman’s lips quivered, but words would not pass them.

“If the Emperor has loved his old servant, then he can also let her live her last days in peace,” said the young woman.

The stranger hesitated still, but suddenly his dark countenance brightened. “My friends,” said he, “whatever one may say of Tiberius, there is one thing which he has learned better than others; and that is—renunciation. I have only one thing more to say to you: If this old woman, of whom we have spoken, should come to this hut, receive her well! The Emperor’s favor rests upon any one who succors her.”

He wrapped his mantle about him and departed the same way that he had come.