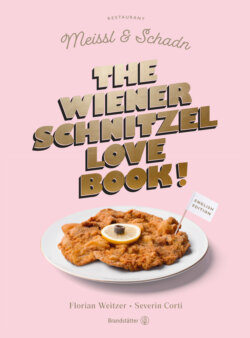

Читать книгу The Wiener Schnitzel Love Book! - Severin Corti - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTrue Viennese have a genuinely religious relationship with their schnitzel – argues

SEVERIN CORTI

Schnitzel is a religion

When a priest celebrates the rite of transformation at Mass on a Sunday, he will hold up the bread and state: “This is my flesh.” Proper Viennese Catholics – and the overwhelming majority of the population has at least grown up in the faith – will certainly tend to view this transubstantiation with a lesser degree of wonder than the rest of humanity. After all, one of the essential aspects of the dish which defines their home city is a capacity to look like bread whilst actually being meat. The central tenet of Christianity becomes reality in the Wiener Schnitzel, at least from a culinary point of view. Turning meat into bread – or vice versa – is part of the daily business of life for a chef in Vienna.

There was, however, another reason why Catholicism’s numerous fasting rules and its inherent aversion to joys of the flesh made Vienna an ideal breeding ground for the emergence of a delicacy such as the schnitzel. The sins of the flesh come mercifully wrapped in a shell of egg and breadcrumb. They thus reward the palate of the connoisseur in a chaste and yet crispy manner. Meat is by no means the only thing to be baked in a concealed way within such a coating. In Vienna, fish, meat loaf, sausage, thick slabs of Emmental cheese, various kinds of vegetables including cauliflower, asparagus, mushrooms and sliced and blanched celeriac and even goulash and rissoles are all likely to find themselves rolled in breadcrumbs. The same goes for virtually anything else which does not move. This opened up plenty of opportunity for deliberate confusion during times when the fasting laws were still taken seriously. When a neighbour lustfully swallowed a golden brown parcel on a prescribed fasting day, who could really tell whether it contained meat or not?

The Wiener Schnitzel consists of veal, flour, egg and white breadcrumbs (plus the highly important addition of a large amount of cooking fat). It is a living legend of Austro-Hungarian cuisine and therefore also constitutes an object of religious debate in its own right. Quite a few Viennese even advocate that status of a separate religion should be conferred on the schnitzel. This notion would include blasphemy, schism and all other related elements. Simply to state that a Wiener Schnitzel must be made of veal and should exhibit a rich sheen when correctly breaded is an insufficient explanation for the rationale behind this particular biblical dance around the Golden Calf. Whereas the rest of the world indulges in schnitzel on two or three occasions a year only, an average inhabitant of Vienna is likely to do so twice or three times a week. The Viennese are thus able to deal with this Holy Sacrament in a highly familiar way. The Wiener Schnitzel is often derided in common turns of phrase used in everyday speech (“breadcrumb carpet”). But the power of faith becomes apparent once such defamation descends into blasphemy.

It is now high time to define what this object of adoration actually represents and to consider its orthodox preparation. The starting point is a piece of meat from the leg of a suckling calf. This needs to weigh around 140 grams and should not be sliced too thinly. It should also definitely not be too thick. Traditional Viennese butchers will refer to these cuts as Fricandeau, Nuss or Schale (thick flank, flank or topside). A metal meat flattener or the non-corrugated end of a schnitzel beater (commonly known as a hammer) is then used to thump this schnitzel to a thickness of around half a centimetre. Under no circumstances should it be beaten any thinner. The schnitzel will otherwise dry out during the cooking process and merely become a fibrous carrier for the flour, egg and breadcrumb coating. The correct Viennese term for this coating is the “Panier”. The feeling is that uncoated meat is uncomfortably naked. Indeed, the locals still make use of the expression “Einser-Panier” (a really crisp coat) to describe a particularly becoming suit of clothes.

The legendary chef Franz Ruhm was the author of a standard work entitled “What shall I cook today? Viennese recipes”. One of the sections in this book, which ran into countless editions, provided highly precise instructions on how to prepare a schnitzel. This description was couched in Ruhm’s own inimitable (if slightly laborious) style. “The sequence of the breading is as follows. Salt the schnitzel and dredge both sides in flour. It should then be dipped in a whisked egg mixture which contains half an eggshell of water and a teaspoon of oil for each egg used. The schnitzel should then be coated in breadcrumbs, preferably of the same size. The crumbs should only be lightly pressed into place. Many people like to tap or knock the coating into position, but this is something which should never be done. The coating should always be applied shortly before the dish is due to be served. If a breaded schnitzel sits around for too long, the crumbs will start to absorb the juices of the meat. A tender and crispy result will then be impossible to achieve. One frequent outcome in such cases is that the coating will completely soften during the cooking process and fall off. (…) The cooking fat must be very hot. Test the temperature by dipping a moistened fork. A furious hissing noise should ensue. There must be enough fat in the pan to allow the schnitzel to “float”. The minimum height of the oil in the bottom of the pan is the thickness of a thumb. A schnitzel placed in well heated fat can become golden brown on the underside in as little as a minute and a half. Turn it over and bake on the other side for the same period of time. Drain well and garnish with a slice of lemon and a few sprigs of parsley. Serve as quickly as possible. When preparing more than one schnitzel, these should not be laid on top of one another. Do not cover a schnitzel to keep it warm because this will cause the breadcrumb coating to go soft. The best way of keeping your schnitzels hot is to put them into a medium oven with the door open.”

The instructions above offer especially detailed guidance. They are quite unlike Ruhm’s other recipes, which are mostly only a few lines long. This approach is taken because Ruhm views the schnitzel as the very centrepiece of Viennese cuisine. At the same time, however, the recipe also features a number of astonishing omissions. Ruhm is well aware of the controversial territory in which he is operating and does his very best to avoid any of the traps which could call his authority into question.

In Vienna, fish, meat loaf, sausage, thick slaps of Emmental cheese, various kinds of vegetables including cauliflower, asparagus, mushrooms and celeriac are all likely to find themselves rolled in breadcrumbs.

Which sort of fat should be used? What accompaniment should be served? Given the fact that schnitzel is a dish which generates the kind of notoriety which shapes national identity, issues such as these should really have been clarified a long time ago. One of the consequences of the personally close relationship which the Viennese enjoy with the schnitzel is that they insist on individuality with regard to some essential details. Although the orthodoxy of the recipe is of doubtless importance as a mediator of truth, the reality of the faith is recompiled in an entirely individual manner in the stillness of the kitchen. Clarified butter is the cooking fat of choice amongst representatives of high-end Viennese cuisine. As far as some people are concerned, however, the resultant taste of the “Panier” is simply too reminiscent of a cake. For this reason, most restaurants in Vienna have now made the switch to vegetable oil. At the very most, chefs will cheat by brushing the cooked schnitzel with a little brown butter in order to bring a note of butteriness to the overall composition. Lard is still preferred out in the countryside and by many families cooking at home. This was by far the most common cooking fat until a few decades ago and is still capable of adding a decidedly rustic and incomparably sumptuous nuance. Serious and protracted discussions on the right cooking fat to use take place at the tables of Viennese pubs. These debates are likely to continue until into the distant future.

Although the Austrians no longer have an Emperor, somehow they still hanker for the golden age of the monarchy. At least the Wiener Schnitzel still enjoys worldwide fame and is held in high esteem by the crowned heads of the world. This all helps. Some of the known facts regarding Elvis Presley are as follows. He was the “King” and famously learned only four words of German whilst completing his military service in the country. But, alongside “Auf Wiedersehen”, these also included “Wiener Schnitzel”. This has remained a source of pleasure for the Viennese down to the present day. Elvis sometimes confused the phrases and was prone to taking his leave with an “Auf Wiener Schnitzel”. In Vienna, this is viewed as a particular compliment.

This aside, however, there is certainly some room for improvement in our American friends’ understanding of the schnitzel. One particularly odd indication of this can be found on the website www.wienerschnitzel.com, which uses Gothic lettering to promote its delivery service. This alone would be enough to flatter the good folk of Vienna. They might, however, be unsettled by the fact that “Wienerschnitzel” actually sells only hot dogs. Sometimes people stray from the path of true faith in a way which is completely unforgivable!