Читать книгу Richard Rive - Shaun Viljoen - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

In a commemorative article on Richard Rive in the Mail & Guardian Review on 7 February 1991, a year and a half after he was brutally murdered, Nadine Gordimer begins: ‘When someone of marked individuality dies and those who knew him give their impressions of him, a composite personality appears that did not exist simultaneously in life.’ This biography attempts to depict Rive as ‘a composite personality’ but from partial and selective vantage points. My account of Rive’s life assembles a multitude of voices and perspectives to compose a man who lived many lives simultaneously and who was a larger-than-life presence, an exceptional teller of stories who engendered not merely memories of encounters with him, but memories recast almost always as exceptional and entertaining stories.

This biography is primarily concerned with the way Rive embodied a vision of non-racialism in his often angry protest fiction, his literary scholarship, his interventions in education, sport and civil society, as well as in an inner life that battled contradiction between vocal assertiveness and tense silences. It tries to identify and delve into some of these strange but not atypical contradictions that pervaded his public and private personae, especially those related to colour and sexuality that have marked or masked his sense of self. Even while facets of this biography will be familiar to many readers, it is a portrait that I suspect not even the few who knew him well will recognise in all its aspects. Our experience of others is always only partial. ‘His cultivated urbanity,’ Gordimer continues in her tribute, ‘glossed over but couldn’t put out a flowing centre of warmth and kindness within’. Others could find at his centre only arrogance, self-centredness and abusiveness. Milton van Wyk, an admirer and younger friend of Rive’s, highlighted these contraries when he described how many responded to Rive: ‘Richard was a generous man if he liked you, scathing and arrogant if he didn’t. He enjoyed belittling people and loved attention, but there was a side to Richard very few people saw and that was of a man wallowing in loneliness.’1

Rive’s main body of work between 1954 and 1989 – twenty-five short stories, three plays, three novels, numerous critical articles on literature, three edited collections of African prose, an edited collection of Olive Schreiner’s letters, poems and a memoir – recounts, in a range of tones, the iniquity, brutality and absurdity of life under apartheid. His counter to apartheid backwardness was a strident and articulate egalitarianism that, in his later years, became somewhat muted and refracted through an introspective rather than a declamatory voice. Even his edition of Schreiner’s letters reflects his interest in a writer who opposed colonial oppression with an insistent and, in her context, radical liberalism. In some of his earlier short stories, the cry against injustice is too strained and obvious but, even here, his flair for telling a dramatic, clever and crafted story is clearly apparent.

District Six, where Rive was born and raised, was a colourful, cosmopolitan residential area adjacent to the centre of Cape Town. It was declared a ‘whites only’ area on 11 February 1966 by the Nationalist government, in terms of the 1950 Group Areas Act, and razed to the ground by the early 1970s. Just a decade later, it had become a symbol of all forced removals of people of colour throughout South Africa, an iconic space of contestation and memorialisation. It was symptomatic of a larger resurgence of resistance in South Africa and on the subcontinent after 1976, which resulted in the birth of new, defiant narratives reclaiming space, memory, rites of passage and return. Rive’s ‘Buckingham Palace’, District Six was one such story and it played a significant role in exposing a new generation of younger readers to his work, ensuring his continued prominence as a South African writer and public intellectual nationally and internationally in the late 1980s and beyond.2

The novel ‘Buckingham Palace’, District Six has been a popular prescribed text for high school learners at various grades in the Western Cape, as well as elsewhere in South Africa and in other countries. Nine years after his death, in 1998, the District Six Museum in Cape Town hosted a retrospective workshop on Richard Rive and District Six for teachers, writers and academics.3 These occurrences reflect the continued interest in Rive and his work, particularly as part of a broader national and regional preoccupation with the processes of reconciliation and reclamation. The memorialisation by the District Six Museum of past and present contestations over District Six, as iconic of cityscape, ownership and rights of habitation and access, includes a memorialisation of Rive as one of the writers born in and concerned with the District. The museum and its educational programmes have attracted thousands of young local students and international visitors to its exhibitions, programmes and archives annually. This has played a major role in recreating and sustaining interest in the life and history of the area, and the associated forced removals and current fraught process of return. As a result, wide interest in Rive’s life and work has been guaranteed, it seems, for at least the next few generations, not only in Cape Town and the Western Cape, but also nationally and internationally.

A one-man play on Rive’s life and work, A Writer’s Last Word, written by Sylvia Vollenhoven and Basil Appollis, premiered at the Grahamstown Festival in 1998 and was restaged at the One City, Many Cultures festival in Cape Town in 1999. Appollis also directed a stage adaptation of ‘Buckingham Palace’, District Six (for which he and I wrote the script) for the Drama department at the University of Cape Town in March 2000, and for Artscape Theatre in Cape Town in 2001. The South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) has considered serialising the novel for television and Appollis is working on a film version of the book. Rive insists on continually resurfacing in the decades after his death.

In the period approaching the twentieth anniversary of the 1994 elections, sometimes referred to as the period of post-transition, the field of literary studies is intensely preoccupied with the literature of the present, of the ‘now’, and with attempts to characterise post-1994 South African literature and culture, particularly with regard to the new forms and subjects of writing that have emerged. This, in part, has resulted in diminished interest in pre-1994 literature, especially in the work of black South African writers. Less attention seems to have been paid to the way the post-1994 period has freed up the act of reading. Just as writing has been freed of the obligatory social and political protest, reading has also been unhinged from old black and white thematics and allowed to proliferate in hugely variegated, exploratory and eccentric ways. New kinds of reading frames will allow us to revisit our literary legacy and find in it new meanings, new pertinence. Certain interpretations of Rive’s work in this biography would never have been possible under apartheid. Comrades (and I) would have seen my queer reading of ‘The Visits’ as defaming Rive, and would have dismissed it as self-indulgent and individualistic, detracting from the priorities of the struggle.

In compiling this biography, particular strands of Rive’s life, thought, work and times are continuous refracting lenses in the narrative, skewing the biography into idiosyncratic angles – looking at those parts that interest me. The first of these is a preoccupation with the idea of non-racialism to which Rive not only subscribed, but which I suggest is at (as Yeats puts it in ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’) ‘the deep heart’s core’ of his being, of his private, civic and writing life. This belief in non-racialism coexisted, often in tense fashion, with his angry humanism and, paradoxically, with his own peculiarly racialised self-fashioning. Large swathes of the past from which Rive comes, and which he also helped to form, are fast disappearing.4 Invaluable and luminous moments of personal memory are thus rapidly fading as his family, associates, colleagues and comrades die or forget. The past of Rive’s era is currently being fiercely contested on a multitude of levels.5

Rive, in his educational, civic and literary work, entered the conflicts of apartheid South Africa from a consistently nonracial position, to defend people of colour from imposed ignominy and deprivation. This way of envisioning human relations is undervalued and even devalued in post-1994 South Africa because neo-liberal economic and attendant social policies of the South African government, its global partners and corporations, despite the rhetoric of non-racialism, have reinforced old intersecting racial and class barriers which suit their profit-driven agendas.6 While the term ‘non-racial’ has been widely adopted currently as nomenclature for the state’s position and as a description of the African National Congress (ANC) policy in the days of struggle, what the ANC, now the ruling national party in South Africa, draws on and practises post-1994 should in effect be called ‘multiracialism’. Even the liberal 1996 Constitution of South Africa, which insists on the equality of all races, nevertheless continues to use the term ‘race’ in an unqualified way. Neville Alexander puts this contradiction we live with cogently: ‘The fact that the relationship be tween an unavoidable national South African identity and the possible sub-national identities continues to constitute the stuff of political contestation in post-apartheid South Africa today demonstrates clearly how tenacious the hold of history is on the consciousness of the masses of people.’7

The assumed existence of different ‘races’ or ‘sub-national identities’ makes reconciliation between groups the most urgent task in contemporary South Africa, rather than, as is implicit in Rive’s brand of ‘non-racialism’, the abolition of the very notion of race. The current terms of the national census and mechanisms of employment equity and redress, particularly the national policy of affirmative action, serve to entrench notions of ‘race’ and of racialised perceptions and consciousness. These operate on the basis of racial profiling, which serves to advance a minority of black middle-class citizens rather than address much more fundamental questions of poverty, land and employment. This fairly hegemonic ‘racialised’, ‘multicultural’ mindset – ‘we are different but equal’ – common in contemporary South Africa and prevalent elsewhere globally, is identified by Cornel West as perpetuating fraught social relations in the United States in recent years. He instead suggests that, unlike the ‘othering’ positions of the American conservatives and liberals, we need ‘to establish a new framework … to begin with a frank acknowledgement of the basic humanness … of each of us’.8 Rive’s notion of non-racialism would completely concur with West’s emphasis on a human and national commonality, rather than primarily on racial distinction and ethnic difference.9

Does Richard Rive have anything to say to us in the twenty-first century in a markedly changed South Africa, so implicated in a firmly neo-liberal and rapidly fomenting global order and with a persistent, viral residue of the old colonial apartheid past? The prominence of the ‘race question’ in contemporary South Africa has resulted in renewed debate on questions of race, division, perception and racism in our society. This is not peculiar to South Africa, of course: one finds parallel concerns in other parts of the world, especially in North America, Britain and Europe. A re-examination of Rive’s life and work entails a reflection on his fight against racialism and for a well-defined non-racialism. This book, and the continued interest in Rive’s work and life, will, it is hoped, contribute to current debates about what kinds of knowledge we need to generate about ourselves and others to establish a truly ‘new’ non-exploitative South Africa.

Renewed interest in notions of ‘coloured identity’, part of an increasing trend in South Africa, which interrogates and/or affirms particular constructions of personal, ethnic and national identity, or what Desiree Lewis eloquently calls ‘“new” fictions of freedom and selfhood’, has ironically resulted in a resurgence of interest in Rive’s life and work.10 Rive himself resisted the notion that he was coloured and his non-racialism saw this classification as a creation by colonialism and apartheid, as part of the divide-and-rule politics of European domination. In so far as this position was a direct ideological retort by a segment of the oppressed intelligentsia, Crain Soudien’s classification of it as ‘counter official’ is useful, since this stresses the oppositional genesis of this stance to the notion of being coloured.11 If he were still alive, Rive would probably not only have baulked at being seen as a ‘coloured’ writer but would in all likelihood have decried attempts to give credence and respectability to this kind of racialised identity.

The subtitle refers to my wanting to go beyond Rive’s declarations about his life and struggle. I am interested in the silences in his life and work, and what I find to be encodings of homoerotic desire and alterity, and deeply personal anxiety about the self in his world, in his fiction and some of the other work. Alongside the anger against injustice that sometimes made his authorial voice gratingly obvious, Rive is remarkably silent, in both life and fiction, on questions of homosexual desire and his own homosexuality. The exploration of sexuality and my queer readings of various works are the parts of this biography that Rive undoubtedly would have deplored. Yet these are dimensions of the man and his work that I found engaging and which have not yet been explored, except to a limited extent in a chapter on ‘Buckingham Palace’, District Six by Brenna Munro in her recent work South Africa and the Dream of Love to Come.

Exploring issues of homosexuality raises ethical considerations about making public the private, particularly because of the absence of any direct link between Rive’s homosexuality and his creative output, and also because of his own very evident silence about his homosexuality throughout his life. Alf Wannenburgh remarks in his memoir of Rive that ‘there were large areas of his own inner life that he was not prepared to disclose, even to those who knew him well’.12 Rive’s friends and associates had widely differing opinions about addressing the topic of his homosexuality, from ‘tell everything’, as advocated by Stephen Gray, to Es’kia Mphahlele, who ‘had no idea’ about Rive’s being gay, implying, it seems, as many did in interviews, that his sexual preference was never known to them or, by implication, of no consequence as far as they were concerned.13 Yet others refuse to talk about it and one senses the extent to which for many, even in our own time, homosexuality remains a taboo subject or ‘irrelevant’ – an invasion, it is felt, of the person’s right to privacy. Yet, as William McFeely insists, ‘as either the writer or the reader engages in a biography or autobiography, there is a conjunction of the private and the public’.14

We all draw the line between the private and the public but at different points. How far do you go? And why go there? A tension of competing interests marks where the border should be, as recognised by Gray when he says that ‘all literary biography is a tug-of-wishes between the private being’s will to reticence and the publicist’s to disclosure’.15 As a biographer, I am convinced by the idea that the personal and historical are inextricably linked. I nod at Robert M Young when he says that ‘one of the things I most like about biography is that it celebrates … the history of ideas, narrative, will, character and the validity of the subject’s subjectivity’.16 I am curious about the connection or apparent absence of connection between the private and the public, the subjective and the social, in particular with regard to questions of desire and sexuality. This biography does not ‘out’ Rive – his being gay was widely suspected, whispered about or guessed at and even known about, especially in his adult years, and his murder and the subsequent widely reported trial of the two young men accused of killing him finally established his homosexuality as public fact. Unlike the dominant notion of ‘being homosexual’ that pervades Western ideas of identity, Rive’s precarious simultaneous state of being and not being gay is far more dynamic, all the more fraught, a space of sexual being that prevails widely, especially in postcolonial contexts where fixed categorisation is often resisted and alien to lived experience.

In writing this book, I have attempted to walk a line between empathy for Rive’s own desire for privacy and my own curiosity about silences, queer literary encodings or readings and sexuality. A constant image throughout the project has been an awareness of Rive looking over my shoulder as I write his life; not infrequently I have had to remind him this is my version of his story, not his. Rive’s sexual life comes into focus to explore possible meanings of these tense, visible or veiled intersections, rather than appearing for their own sake or merely for reader titillation.17 What level of detail is used and to what end? The exploration of sexuality is carried out, it is hoped, with contextual and ethical considerations constantly in mind. As I explored aspects of Rive’s public and private life over the years, I realised how partial I had become to his ideas, his convictions and the way he navigated the trauma, doubt and dilemmas in his work and life. The nature of Rive’s strained relationship with his family, his unspoken homosexuality and proclivity for young men and the violent and mysterious circumstances of his death were matters some interviewees found sensitive and chose to avoid, explain away or refuse to talk about altogether. While responses to these questions were formulated and refined and redefined during the process of transcription and writing, I kept falling back on the response that, while attempting to maintain empathy with Rive and his assumed sensibilities, I needed to make the narrative my own, pursuing lines of inquiry I could justify as valid, useful, informed and considered. This work attempts a historically accurate account of Rive’s life as far as possible, but combines this with the particular lenses I chose in order to refract his life. I had hoped to unearth some of the fascinating enmeshing of the intensely personal and private on the one hand and the macro socio-economic on the other, but, for the most part, the nature of such entanglements continues to baffle.

Lastly, I read Rive’s life and fiction as distorting echo chambers of each other. Reading real authorial life from clues in the fiction – reading the fiction as symptomatic of authorial consciousness and life facts – and inversely reading fiction in the light of that life, risks downplaying the mysterious interconnectedness and often autonomous existence of these two realms. Placing them side by side to compose a fuller portrait of Rive’s life is helped by his own insistence that his life and fiction were closely linked; on many occasions he insisted that his stories and novels were ‘faction’. Biographer Michael Holroyd believes that the main business of the literary biographer is to ‘chart illuminating connections between past and present, life and work’, typifying the strong and very productive empiricist tradition of anglophone biography.18 Such attempts at mapping between life and work are not simple one-to-one matches but are instead intricately threaded conjoining and disjunctures, in constant tension and often contradictory, mediated by the dynamics within and between such diverse domains as individual imagination and macro socio-economic contexts.

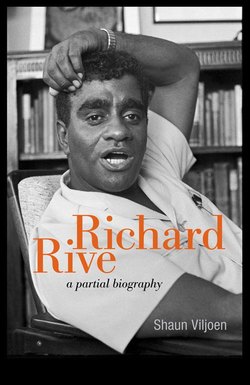

This biography proceeds chronologically from shortly before Rive’s birth in 1930 to his death in 1989 and slightly into the posthumous period. I give greater prominence to momentary images – large photographs that mark parts of Rive’s life on which I reflect closely in an attempt to cohere the narrative around the specific image. I place the photographs in positions where they talk to a segment of the text, rather than, as is more conventional in many biographies, interspersing the photographs, chronologically ordered, in a few compressed folders which form an impressionistic visual narrative illustrative of the story in the text. I do close readings of the images to echo, contribute to or interrogate the main narrative in the text. I use nine images, all but four by George Hallett, a world-renowned photographer who was a pupil and lifelong friend of Rive’s, and who believes it was Rive who opened him up to the idea of becoming an artist. These particular photographs also suggest their own mute narrative that Hallett imparts to us about Rive. Only very particular, fleeting moments and gestures become visible, but all other times of Rive’s life remain visually unseen.

The cover photograph was taken by George Hallett in 1966 or 1967, when Rive was in his late thirties, just before he left for Oxford to do his doctorate and Hallett himself went into exile. Taken in Rive’s flat in Selous Court, Claremont, Cape Town, the image, with the backdrop of books ordered on bookshelves and framed artwork on the walls, features in the foreground the comfortable, confident, even cocky man in a typical gesture of his, arm over the head as if to frame himself as he is framing his words, fingers containing the temple in a gesture associated with thought. He is seated and, with his eyes overlined by those distinctive fulsome eyebrows, he stares directly at the photographer, his protégé, and beyond at us, not smiling but holding forth, claiming a point, loud, yet, as is the way of a photograph, silent and therefore forever ambiguous. He talks to us but he is mute.

Late twentieth century and early twenty-first century work on biography (Paula Backscheider, Michael Holroyd, Hermoine Lee and, in a South African context, Mark Gevisser, John Hyslop and Roger Field, among others) reveals a much greater degree of self-consciousness about its project than earlier work from the late nineteenth century onwards, which reflected more confident, unquestioned assumptions about epistemology and objectivity. What film-maker and photographer Errol Morris says of photography is equally true of biography – photographs (biographies) edit reality; they ‘reveal and they conceal’ and tell us something of the real but never the whole story; they can document, but they also skew; they can tell us something, a partial truth, but simultaneously remain a mystery.19

I have used archival documentation, Rive’s own work, writings on Rive, personal interviews and my own memories of the man. Facts of his life matter in the biography, and in this regard I have drawn heavily on Rive’s memoir, Writing Black, as well as other sources, but why specific details have been chosen and how I then make sense of them matters equally. What does one select, why, and then how to connect or resist connecting these chosen facts, and to what end? I have used a combination of conventional third-person narration, with occasional more intrusive first-person narration (particularly in those times when my life overlapped with Rive’s in the 1980s and when I worked with him at Hewat College of Education) with interlocking narratives by Rive himself and anecdotes and stories by those who remember him.

I came to know Rive in the mid-1970s through his association with Non-European Unity Movement (NEUM) intellectual Victor Wessels at discussions and parties at Victor’s home in Fairways and then in Walmer Estate. I also encountered him in this period at forums like the Cape Flats Educational Fellowship, where he often gave workshops on English and African literature for high school students. I also saw and heard him in meetings on civic and sports issues during the late 1970s and early 1980s, but we were by no means friends. In fact, I thought little of his work and disliked his pompous and affected manner; he in turn thought little of me (or so it seemed), sensing perhaps my reservations about his work (I have not a single signed copy of any of his books), my natural reserve generally and my preference, unlike him, for remaining in the shadows, away from public glare.

It was only during a meeting in London in 1986, when I was a student at London University and he was passing through to secure a visiting professorship at Harvard, that we really spoke to each other over supper in North London at the home of Maeve Heneke, a mutual friend. It was then that he recruited me to take up a teaching post at Hewat College of Education, in fact to take his place while he was on leave teaching at Harvard. He was head of the English department at the college, where I worked closely with him from 1987 to his death in 1989. A friendship of sorts developed, but there always remained a measure of distance between us. Tension increased between us at certain times, such as during my participation in a Hewat College stage production by colleague Colleen Radus of his novel ‘Buckingham Palace’, District Six in 1988, when he disliked the way I had rescripted parts of his own script. He nevertheless remained generous and at times very warm towards me, asking me to housesit on occasion, and on his last birthday before he died, we had supper together with two other Hewat colleagues, Marina Lotter and Martin Dyers, both of whom he liked and who in turn really liked him. At the time of his death, my admiration for him as a writer and a man had grown, but I remained sceptical of the literary value of much of his work. The more I thought and uncovered about him and the work over the next twenty years, the larger he has grown in my esteem, tempering an initial ambivalence about him as a writer and a person and learning to understand the limitations of my then narrower notions of what constitutes literature. I began to grasp his immense courage, drive and vision as a writer.

Ten years after his death, I decided to undertake this project while working at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. There was no existing biography of Rive. It was also becoming clear that that old racism was persisting in the ‘new’ South Africa at the turn of the century and taking on new, often insidious forms. A biography of Rive would allow me to share more widely our joint commitment to non-racialism as we had known it and perhaps contribute to local and national debate. It was in the course of this research for more than a decade that I started to rethink some of my harsher and decontextualised judgements about Rive’s work and character and came to realise how large he loomed, and still does, as a character with his acerbic wit and humour, how lonely and troubled he was and, above all, what a compelling teller of tales.

There are other overlaps between my own and Rive’s life. We were both classified by apartheid as coloured and styled by the times as ‘coloured intellectuals’ despite our resistance to this; we were the products of the political outlook of the NEUM and felt compelled to assert a (Western) cosmopolitanism that stemmed from resistance to the balkanising tribalism and racism being fostered by the South African ruling classes; like Rive, I have ended up being markedly ‘anglophilic’ in a certain sense (teaching in English departments, for example) and yet, at the same time, we both found ourselves countering that very impulse and propagating African literature and local writing through our work at secondary and tertiary educational institutions; like Rive, although for different reasons (and a few of the same?), I am uneasy with the label of being ‘gay’ as definitive of who one is.

Finally, a biography of Rive needs to capture something of the spirit of the man most of those interviewed remember – his wit, sometimes scathing, sometimes entertaining, sometimes self-parodying; his natural ability as a raconteur, making him a memorable teacher, colleague and friend. In the end, I hope the Rive I have refracted is what Virginia Woolf hoped for in her fictional characters: ‘I dig out beautiful caves behind my characters … I think that gives exactly what I want: humanity, humour, depth.’20 Reading Richard Ellmann’s biography of Oscar Wilde, one wonders to what extent Rive echoes dimensions of Wilde – the dandy, the raconteur, the Magdalen graduate, the aphorisms, the drive to write, the love that dare not speak its name, the changing of dates of birth to make himself a little younger, the tragic ending – were these a strange case of fate, or perhaps, in part at least, coincidences cultivated by Rive?

In 2011 I found myself in Berlin trying to delve into Rive’s connection with the old East Berlin, which was where his first book, African Songs, was published in 1963. It was then that I had, for the first and only time, a dream in which Richard appeared.

He visits me in my small townhouse in Wynberg (as he did not long before he was killed) and I am showing him a passage from my biography. He thrusts back the book and sneers, ‘That is wrong! You’ve got it completely wrong.’ I am about to say, ‘But … I got that part from … Colleen’ then choke on my words. We descend the narrow stairs with him behind me. I turn to look over my shoulder and catch Richard about to push me down the stairs. I wake up.