Читать книгу Richard Rive - Shaun Viljoen - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPart I: 1930 – 1960

Chapter 1

The great influenza pandemic of 1918 and 1919, ‘the Spanish flu’ as it was called, is thought to have started in military camps in Kansas, in the United States. From there, it rapidly spread to the rest of the world killing, it is estimated, between 20 and 40 million people, more than had died in the five years of the First World War.1 The plague reached South Africa within months. In Cape Town, a vital stopover on the route of humans and goods between East and West, a young, married, working-class couple, Nancy and Joseph Rive, ‘coloured’ in the racialising language of the time,2 had started a modest home in the area of District Six, abutting the centre of the burgeoning port town at the base of the monumental Table Mountain. The area was created as Cape Town’s sixth municipal district in 1867 and by the time Nancy and Joseph moved there, it was less of the edgy area once known for its crime and prostitution and was developing into a vibrant, cosmopolitan and mainly working-class residential area.3 District Six was, however, like all land in the newly formed Union of South Africa, a contested space where white supremacy and resistance to racial oppression did battle. The ANC had been formed a few years earlier, in 1912, by African intellectuals, ‘bitter and betrayed’ by their exclusion from the common voters’ roll, while the white leadership of the new union divided the country into wealthier white and impoverished black areas with their 1913 Natives Land Act.4

It was the District, as it was commonly known to locals, that was to become home to the young Richard Rive in the 1930s and early 1940s, but from which he quickly fled as a teenager to escape the constraints of his family circumstances and to make something of himself. It was the District, however, which would prove to be a perennial preoccupation of his imagination and would be intimately associated with his best work.

In 1918 Nancy Rive gave birth to her seventh child, a little girl she called Georgina, most likely after the British monarch at the time, King George V. Like vast numbers of residents of the District, the Rives were great admirers of British royalty, whose portraits were displayed in their homes. The other six Rive children were Joseph, the eldest boy, and then came David (known also as Davey), Arthur, Harold, Douglas and another girl, Lucy. Soon after Georgina’s birth, tragedy struck the family and Joseph Rive (senior) died, a victim of the Spanish flu that, quite strangely for influenza, afflicted mainly younger people in their twenties and thirties.5 In the wake of her husband’s death, in a world ravaged by war and a country ruled by white supremacists, and with seven mouths to feed, the young widow was in for a long and hard time.

Twelve years after Joseph’s death, in 1930, when Nancy was thirty-eight-years-old and Georgina almost a teenager, the single mother gave birth to a laatlammetjie (Afrikaans, a child born many years after its siblings). Richard Rive’s birth, on the first of March that year, was shrouded in controversy and secrecy, and marked him as exceptional from the beginning. Interestingly, in Writing Black, Rive gives his date of birth as 1931. However, his birth certificate states clearly 1 March 1930. There is wide discrepancy in published texts – 1930, 1931, 1932 and 1933 are all given as dates of birth. At Hewat College, where Rive worked, it was rumoured that he gave a false (later) date to make himself appear slightly younger. It is strange that, for someone as fastidious about detail as Rive, so many dates of birth prevailed even while he lived. He often got dates wrong, for no apparent reason.6

The sizeable age gap between Richard and his siblings was to contribute to the young boy’s acute sense of alienation from the family as he grew up. He was very much a part of the family yet also very apart from it. The United States was the source of the tragedy that had robbed Nancy of her husband; it was also the place of origin of the man with whom she had had a fleeting affair, who was to father her eighth and last child. His father was a ship’s hand called Richardson Moore, who abandoned him and his mother when Rive was just three months, and was not seen again by either. As an adult, Rive tried on a number of occasions to track down his father in the United States. The only trace of his father was in Richard’s name, for his mother had given the name ‘Richard Moore Rive’ on his birth certificate. In his memoir Writing Black, published when he was fifty-one years old, Rive says of his father: ‘About my father and his family I know almost nothing. He died soon after I was born and was seldom mentioned in family circles. Perhaps a dark secret lurks somewhere.’7 Is Rive using ‘died’ here metaphorically to account for the absent father? For, as is clear from Rive’s correspondence with writer Langston Hughes in the late 1950s, the father had not in fact died but rather disappeared leaving no trace whatsoever. Hughes (1902–1967), the iconic black American intellectual, poet, fiction writer and dramatist, and a leading figure of the black American literary explosion of the 1920s, the Harlem Renaissance, was to play a seminal role in Rive’s writing life.

In Writing Black Rive, for some reason, cannot say directly that his father was a black American but instead suggests this circuitously by recounting an incident at an athletics meeting at which he had performed particularly well, and where a black American woman, an intimate friend of his mother’s, commented affectionately to him: ‘“They can’t beat an American boy, can they?” … So possibly the Black strain came from my father and came from far over the Atlantic.’8 Rive was clearly tentative, even reluctant, about revealing this aspect of his life, revealing only certain details to particular audiences. He was restrained not only about his father it seems; in his adult life he rarely spoke about his mother, even to close friends.

By the time the older Rive comes to write this account of his life, he undoubtedly knows more about his father than he lets on, choosing to embed even these spare facts in circumspect and suggestive narrative in his memoir. However, in a letter to Hughes in 1962, almost twenty years before the publication of Writing Black, he is much more candid about the silence that attended the question of his paternity in his District Six home, a silence clearly stemming from his mother’s deep sense of shame at the affair – a shame compounded by Rive’s dark skin:

A very interesting feature of my life is that my father is an American Negro, but he left home when I was a mere 3 months old. I never saw him. I believe that he might still be frequenting the New York waterfront. He was apparently a ships [sic] cook. Name Richardson Moore. Interesting if we should ever meet again. My mother is from an upper class family, and the subject of my father is never brought up.9

The question of Rive’s paternity, with all its unarticulated proscriptions, shame and even disgust within the family (perhaps even within himself), was the first instance in his life where the equation between shame and silence was a mark on the psyche of the young boy. He is clearly reluctant to reveal the full extent of this ‘dark secret’ in his memoir. Was it just too shameful? Was it too private? Was it of no import in a memoir that, like his fiction, was primarily concerned with exposing the injustices of racial oppression? In the very first line of Writing Black, Rive insists on the selective nature of his autobiography: ‘Some [incidents] are locked away in that private part of my world which belongs only to myself and perhaps one or two intimates.’10 Perhaps the deliberate silence Rive acknowledges, as ‘locking away’ particular incidents and emotions, is not simply a choice to edit out certain details but a multiple, more complex silence – silence about both the world of his family and, later, the very private and closed world of his sexuality.

The young Richard grew up in a ‘huge, dirty-grey, forbidding, double-storied’ tenement building in Caledon Street, at number 201. Rive’s detailed, filmic description of the place is reminiscent of Dickens’s descriptions of inner-city settings:

[It] housed over twelve family units … with a rickety wooden balcony that ran its entire length. There were three main entrances, numbered 201, 203 and 205. All faced Caledon Street. Behind it and much lower, running alongside, was a concrete enclosed area called The Big Yard into which all occupants of the tenement threw their slops, refuse and dirty water.11

The photograph by Clarence Coulson is of this double-storey tenement building in Caledon Street, taken from William Street across the square. Aspects of the photograph were explained to me by Noor Ebrahim and Joe Schaffers in June 2012. Both Ebrahim and Schaffers grew up in the District and knew the young Rive well. Each window represents the living quarters of a separate family and the Rives rented the first dwelling on the left on the top floor, with only a bedroom and a small kitchen, according to Ebrahim and Schaffers who visited the Rive house. The square served as a playground for the pupils from the nearby St Mark’s Primary School during the week. On the left is the community hall, which was also used by the school. The image here is of a Sunday morning, in the early or mid-1960s according to Ebrahim, with the uniformed lads from the St Mark’s Church brigade preparing for their march, which would begin with the tolling of the church bell. An intensely curious audience of dozens of children and adults can’t wait for the show to begin. The evident physical density and dilapidation of the space is overwhelmed by the sense of bustle and expectation, of adults and children living the rituals of a special time and day, a Sunday morning in the District.

Caledon Street, District Six (photographer: Clarence Coulson)

This row of dwellings was, fifty years later, transformed by Rive’s memory and imagination into the row of five conjoined, bustling homes called ‘Buckingham Place’, the locus of communal life portrayed in his novel ‘Buckingham Palace’, District Six. A more realistic and possibly more accurate picture of the domestic life of the family in their home is suggested by Andrew Dreyer, the protagonist in Rive’s first novel Emergency (first published in 1964). The description of Andrew’s home reflects the cramped, overcrowded, Victorian conditions in which Rive’s own working-class family lived in the District:

They occupied three dingy rooms on the first floor of a double-storied tenement flat at 302 … One first entered a landing which smelt damp and musty and echoed eerily when the wind blew through it …Then up a pitch-dark staircase till one fumbled at the knob at No. 3 and entered a shabby bed-sitting room grandiloquently called the dining-room. This was dominated by a huge four-poster bed with brass railings, an old-fashioned couch with chairs to match, and a side-board cluttered with Victorian bric-à-brac. A cheap but highly polished table was squeezed between the bed and the sideboard. A bedroom led off this, occupied by James and Peter-boy. Here another fourposter bed was situated in the centre, with an ancient tallboy leaning against the wall, adorned with a pink and white basin and picture. Two broken French doors led to an unsafe, wooden balcony. One had to go back to the upstairs landing to reach the Boys’ Room which Andrew, Danny and Philip occupied. It contained two beds and a chest of drawers and had the musty smell of stale air and perspiration.12

Growing up in such conditions, confining and dilapidated yet with a sense of respectability and even grandeur, with Nancy’s ambiguous love and care, and an intimacy with only some of his siblings, Rive undoubtedly, like many other youngsters with talent entrapped by circumstance, often retreated into the world of the mind – to books. He also found refuge in the friendship of neighbourhood boys who accepted, admired and were intrigued by his way with words and his wit.

Rive’s brother-in-law Freddie Josias, husband to Georgina, the sibling to whom Rive felt the closest (possibly because they were the two youngest), describes Rive’s family as existing in circumstances that forced them ‘to live from hand to mouth’.13 A schoolmate of Rive’s, Gilbert Reines, says Rive did not have shoes at one time (like many of the children in the Coulson photograph) and that he came from ‘a really poor family’.14 Rive himself talks of their living ‘in an atmosphere of shabby respectability’, playing down somewhat the level of poverty but putting his finger on the quest for middle-class respectability and a ‘decent’ life.15 As a single mother, Nancy struggled to make ends meet, but the cost of keeping the household going by the time Richard was growing up and going to school was supplemented from the wages of older siblings like Georgina, who worked at a city printing firm, Herzberg and Mulne, and the second-eldest brother, Davey, who worked at Flack’s furniture store in the city.

As a respectable churchgoing Anglican, Nancy Rive had her baby boy baptised and later, in his early teens, confirmed at St Mark’s Church on Clifton Hill in the District, just a short walk from their Caledon Street home. One of the few fleeting references to his mother comes in Rive’s memoir and is prompted by his visit, in 1963 while on an extended tour of Africa and Europe, to the Piazza San Marco in Venice. Th ere, he recalls accompanying his mother to present the family Bible to the church and remembers St Mark’s in terms that suggest the church was a refuge from the hostilities of the outside world for the young boy: ‘And the cosily lit warm interior on a Sunday evening when the south-easter howled outside … I was a boy in St Mark’s on the Hill, comfortably dozing through the warm monotony of Evensong.’16

While St Mark’s Church was to feature prominently as a site of communal ritual and resistance in Rive’s work, as it did in the history of resistance to forced removals in the District, he turned his back on religion in his adult life, becoming an atheist – as were many of his left-wing mentors and friends who defended their atheism by, for example, quoting Karl Marx’s dictum about religion being the opium of the people and circulating Bertrand Russell’s polemical essay ‘Why I Am Not a Christian’, which attacked Christian hypocrisy and mystification. The fact that the policies of segregation pre-1948 and those of apartheid after that were rationalised using Christian doctrine increased the alienation of many intellectuals of the time from Christianity (in particular) and religion in general. Many others, though, were drawn to religion and the church as part of their lives; some of Rive’s close friends in his youth – Albert Adams and John Ramsdale – were active churchgoers. One of Rive’s early short stories, ‘No Room at Solitaire’ (1963), exposes the hypocrisy of the Afrikaner characters who profess to be Christian but rudely turn away a sick and pregnant black woman and her husband from their inn. Although a jarringly obvious allegory on the plight of Mary and Joseph on Christmas Eve, the story ends with the racist Afrikaner men having an epiphany of the import of their inhumane act – an ending that reflects Rive’s persistent belief in the possibility for good in everyone, a quality present in all his creative work. Unlike his contemporaries Alex La Guma and Dennis Brutus, Rive was impelled not by a strong sense of anti-imperialist or anti-capitalist ideology, but rather by more liberal convictions about individual and human rights. In this sense, Rive shared more common ground as a writer with his friends and fellow writers Es’kia Mphahlele and James Matthews.

Surrounded by ‘dirty, narrow streets in a beaten-up neighbourhood’, his family, Rive claims, was marked by an obsessive hankering after respectability: ‘We always felt we were intended for better things.’17 The gently parodic tone in which this is said in his memoir, written forty years after this period of childhood, indicates a measure of distancing from these familial aspirations. As a young man in his twenties, though, Rive still identified with them, needing to be ‘respectable’ and ‘civilised’, able to transcend the ‘decrepit’ place he inhabited. He would, in his second letter to Langston Hughes in 1954, excitedly and assertively introduce himself: ‘Age 23 years. I was born in District Six (one of the most terrible slums in Cape Town, although I come from a cultured family).’18 The early letters to Hughes are clearly trying to impress the older, internationally acclaimed figure with the young writer’s knowledge of place and his sense of being ‘cultured’. In this description of himself and his origins, Rive interestingly distances himself from District Six, calling his birthplace a ‘terrible slum’, unlike the affirmative and often nostalgic portrayal in the later novel ‘Buckingham Palace’, District Six. In this description to Hughes of the District and of himself, it is interesting that the qualifier ‘although’ is used to separate the District from the notion of being ‘cultured’. ‘Culture’ was elsewhere and, like his sister Lucy and his brother Joseph, Rive ‘fled the District as soon as possible’.19 Thirty years later, however, when the resistance to forced removals had reached a pitch in the struggles of the oppressed, District Six, like numerous other residential areas (for example, Sophiatown in Johannesburg and South End in Port Elizabeth), became, for him, the country and the world, an iconic space of unjust displacement and of justified reclamation; a place of reinvented and celebrated pasts textured as both real and imagined.

The young Richard sensed himself on the margins of the family – not only was he much younger than his siblings, but he was much darker in complexion and had a different father. This sense of estrangement from family is only fleetingly dealt with in his autobiography where he says that ‘in [his] loneliness’, he cultivated friendships with down-and-out, working-class boys whom his family derogatorily called his ‘skollie friends’ (gangster friends).20 Writing Black is particularly silent on family; Rive’s main focus is to fashion his young self as a reader, budding writer and metonymic voice against racism, an individual who simultaneously represents and transcends the oppressed condition. Above all, Rive’s memoir is protest, an indictment of racial tyranny and its attempts to categorise, to confine and silence him, and to erase the spaces that define him. But of his inner life as a child in a family, the work is remarkably silent. There is no mention, for example, of the death of his mother or what it meant to him. There is more descriptive detail in the portrayal of the character of Mary, ‘proprietor’ of the local brothel that the four-year-old Rive stumbles upon in his neighbourhood. As is the case in the later fictional work, the memoir is marked by the invocation of alternative forms of family and intimacy constituted by fellow writers, work colleagues, sportsmen, a few friends and the young men he befriends. The twenty-four photographs that open Writing Black carry not a single image of the family – there is one of the District and the rest are images of Rive himself in the company of or, through the mechanism of photographic collage, associated with prominent South African and African writers.

Writing Black recounts Rive’s childhood primarily through eyes that see the racial conflicts and dilemmas in South Africa as pervasive. His father’s side provided ‘the Black strain’, the ‘strain’ Rive insisted in his adult life on proclaiming and defending in contrast to the marked silence about it within his family.21 Nancy Rive, who was born into the Ward family from Klapmuts, a small settlement in the Boland area on the outskirts of Cape Town, proudly displayed her father in a mounted photograph (showing him in a cheese-cutter hat with a droopy moustache next to his champion racehorse) which had a special place on the dining-room wall. He is described by Rive as ‘unmistakably white’. Stephen Gray, a fellow writer and long-standing friend of Rive’s, describes Rive’s hair as ‘Saint Helenan kinky’, suggesting that some of Rive’s forebears were from the South Atlantic island.22 One wonders if Gray heard this bit of family genealogy from Rive himself. Nancy’s father was, it seems, a descendant of the Ward family on the island of St Helena. The St Helenan diaspora in the Cape and in other coastal areas of South Africa – Port Elizabeth, Durban, Port Nolloth – often asserted their connection to Britain and were generally resistant to being pigeonholed into racial categories, particularly under apartheid, as ‘Cape Coloureds’. While this attitude marked a progressive resistance to apartheid’s grand plan, there was also among some an attitude that having St Helenan ancestry made you ‘a better coloured’. Nowhere is there any textual reference by Rive to these island origins. If Nancy’s father’s side was fair-skinned, his maternal grandmother, however, Rive guessed, was dark-skinned, as Nancy turned out to be ‘beautifully bronze’ and ‘little was ever mentioned … other than that she [his maternal grandmother] came from the Klapmuts district’.23 There was no proudly displayed photograph of Nancy’s mother. As was the case with vast numbers of South African families living with the intensely colour-conscious and hierarchical legacy of a colonial and segregationist history, darker-skinned relatives were often regarded as shameful and personae non gratae, and were marginalised or completely excised from memory, or relegated to the realm of taboo and silence.

In his first novel, Emergency, Rive bestows on his main character, Andrew Dreyer, elements from his own life. Andrew has a tense and ambivalent relationship with his mother, feeling both intimacy and alienation at the same time. The novel accounts for the estrangement from the mother because of colour:

She had always been strange in her attitude towards him. Sometimes gay and maternal and then suddenly cold and impulsive. He wondered whether it had anything to do with colour. She was fair, like James and Annette, whereas he was dark, the darkest in the family. Sometimes when they walked together in the street, he had a feeling that she was ashamed of him, even in District Six.24

Added to this, the young boy in Emergency gets blamed for his mother’s death from a stroke after she had to brave the wind and cold as Andrew refused to run an errand for her. His elder brother accuses him of being a lying ‘black bastard’ and a murderer, violently beating up the younger Andrew, who then runs away from home, never to return.25

Rive’s brother-in-law Freddie Josias remembers him as a clever, even brilliant boy at school. One of the teachers at St Mark’s Primary School, Ursula Reines (née Strydom), who later became a close friend, remembers that ‘in those days there was the famous old composition that you had to write. Give you a title and sit down and write a composition. And Richard just excelled. I think he had a gift for words.’26 It was Georgina and Davey’s wages that helped keep Richard at St Mark’s until Standard 4 and then at Trafalgar Junior School until Standard 6.27 In Emergency Daniel, an echo of Davey it seems, is the only brother with whom Andrew feels some kinship in the home:

Andrew got on well with Daniel. He was quiet and an introvert, something like himself, without the bitterness and resentment. Daniel was good-looking, soft-spoken and understanding. A regular church-goer, he had very little in common with the rest of the family other than his mother and Andrew. They often spoke, Danny and he, in the quiet hours of the morning while they lay next to each other. His brother was appreciative and honest in his opinions. He liked Danny best of all.28

Josias remembers the young Richard as a very independent boy, even at this early age, who did exceptionally well at primary school. Alf Wannenburgh, another fellow writer and a friend until their relationship soured after decades, believes that St Mark’s, which was Anglican, ‘instilled Anglo-Saxon virtues’ in the mind of the young boy.29 These, however, were already present in Rive’s home and the connection to St Mark’s Church and in the royalist sympathies both at home and in the community, so perhaps it is more true to say that the school cemented the values of his home environment. Rive’s own experiences at the primary school are transmuted into fiction in Emergency, as were other aspects of his outer and inner life. Andrew Dreyer fondly reflects on his origins in District Six in an early flashback:

The boys played games during the first lunch-break, but he was too self-conscious to join in. He stared with wide, black eyes at the teachers and the classrooms and the Biblical pictures on the wall and the miniature tables and chairs and the neat pile of worn readers in the cupboard. See me, Mother, can you see me? And life was beautiful and golden-brown on those apricot days when he was seven.30

What he describes here as the boy’s ‘wide, black eyes’ reflects quite literally Rive’s striking dark eyes but also prefigures the title of his memoir Writing Black. Rive’s alluring eyes are described by his old friend Ursula Reines as ‘doleful’.31 In this passage from the novel, the young boy is sensitive, self-conscious, very observant, immersed in texts and on the outside of the throng, often distanced from family yet immersed in neighbourhood, and with a deep subliminal longing to recreate an ideal mother-child bond. His childhood was not only a dreary and often trying time, but equally ‘beautiful and golden-brown’. The image of the time as ‘apricot days’, the sweet and sour of growing up in the District, is more fully and successfully portrayed in ‘Buckingham Palace’, District Six.

While there are echoes in his fiction of his strong sense of alienation from his family, especially after the death of his mother, while he was still at high school, Rive did not write about this in his non-fiction or in reflections on his childhood or his adult years. He shared the more private aspects of his life with only a very few close colleagues and friends. Interestingly, in Emergency, after Andrew has just left his home following the traumatic death of his mother, his fraught relationship with his siblings is described: ‘He had a kind of revulsion about hearing the news of his family, yet his curiosity got the better of him. He would have preferred to wipe out their existence from his mind.’ Earlier in Emergency, we hear that Andrew ‘was afraid of his elder brother; James had beaten him for breaking one of the dining-room chairs. James was very fair-skinned, a play-white, always cold and aloof’ and ‘[James] … despised Andrew, whose dark skin he found an embarrassment’.32 Rive, like his creation Andrew, felt the internalised racism that was prevalent in his family and caused untold strife and disruption, apparently leading to lifelong animosity between him and many in his family. Josias, however, denies that family members who were only ‘a shade lighter’ than Rive were prejudiced against him because of his dark skin. Long-standing friends of Rive’s, Ariefi and Hazel Manuel, recall Rive’s sisters who lived in Woodstock and that Richard was the darkest of the siblings and that this was patently an issue in the family. Much of the time Rive was raised by his maternal grandmother rather than by his mother and, by his teens, he had left home to board elsewhere. He maintained some contact with Georgina, who kept in touch with him throughout his life.33

In Rive’s short story ‘Resurrection’, first published in 1963, there is a similarly fraught family scenario. Mavis, the main character with whom we empathise, has fair-skinned, play-white brothers and sisters who refuse to acknowledge the existence of their dark-skinned sibling. This story dramatically recounts the terrible pain and humiliation felt by Mavis, spurned and ignored as if she did not exist by those supposed to be closest to her – intense emotions that peppered Rive’s relations with his mother and his siblings. And while these emotions undoubtedly affected him in deeply personal ways, he seemed able to confront them only from the distance provided by fiction, rather than in the closer-to-home autobiographical accounts of his childhood and adult life. In this regard, Rive embodies what Virginia Woolf suggests about the almost impossible act of capturing the momentous social and personal forces that constitute one, the ‘invisible presences’ that elude self-memorialisation: ‘How futile life-writing becomes. I see myself as a fish in a stream; deflected; held in place; but cannot describe the stream.’34

Another factor that kept Rive at a distance from his family, particularly beyond his teenage years and throughout his adult life, was his sexuality. He attempted to conceal his homosexuality from family members and most of his friends for as long as he lived. Many, especially those of his generation or older, only realised he was gay because of the circumstances of his murder which, especially after the trial of the two accused, pointed to the murder of a gay man by young boys with whom he had or intended to have sex. Some of his friends, colleagues and fellow writers suspected that he was gay, while a few knew that he had had relations with younger men. As if out of respect to Rive the influential public figure and educationist, the son of the community who had made a name for himself locally as well as internationally and did them proud, and also perhaps respecting his own obvious wish to remain closeted, combined with the conservative ethos of the times in South Africa, there was, during Rive’s lifetime, a public silence about his homosexuality. Josias claims that Georgina would have been horrified had she known he was gay. She never did realise he was gay or, like many of her generation, possibly refused to recognise something that was beyond her comprehension or moral universe. Josias also says that Rive became especially estranged from his sister Lucy because her husband was hostile to him – perhaps, Josias speculates, because they were jealous of his achievements or perhaps his homosexuality became evident at a later stage and so the hostility increased. Rive must have sensed even at a very early age this fairly widespread socially encrypted disgust for homosexual men and this increased the distance between him and his family. At what age he realised he was gay, or what the terms he used to think about his own sexuality were, remain unknown.

One of Rive’s enduring friends was the artist Albert Adams. They met as fellow students at Hewat College, where Adams was a year ahead of Rive. Adams was much more comfortable with being a gay man at that stage than Rive was and accounted for the difference in the following terms:

I think even in ’53 I knew Richard was gay … Dennis Bullough was a gay chap who lived in Bree Street and he had a partner, John Dronsfield, who was an artist, and Bullough and Dronsfield kept a kind of open house for artists and the like. And Bill Currie was a close friend of Dennis Bullough, and if you knew Bill [as Richard did] you were invited to Bree Street … it was a group of gay people and, you know, if you were … there, you were gay … Already then I knew that Richard was gay; we all knew that he was gay. Although our gayness, I think, was a little bit more open than Richard’s. Richard had this macho-image of course, he was also a sportsman … So he was involved with sports and young people, and I suppose … I don’t know to what degree that also [kept] a halter on him to keep his gayness under cover … It would really not have, not have been accepted had he worked with young men, you know, on the sports field … it was also simply part of Richard’s insecurity. I’m thinking … underneath all this kind of bravado, and this really extrovert, public image that he gave, I think there was a, a real sense of … insecurity on Richard’s part. I’m … almost sure about that.35

Adams was one of the very few friends with whom Richard was open about his gayness, but even with Adams he was reticent about revealing any details of his private sexual affairs.

Rive decided, it seems, not only to keep his sexuality an intensely private matter, but to deflect it by recreating heterosexual stances that could be perceived as indicating his ‘normality’. Writer Es’kia Mphahlele, who first met Rive in 1955 and became a lifelong friend and mentor, was bothered by Rive’s lack of family attachments and also wondered whether his father was from Madagascar because the name ‘Rive’ is so close to ‘Rivo’ or ‘Rivero’. Mphahlele also remembers that Rive did not relate to his brothers because they were not from his father. There was clearly a distance between him and his family, Mphahlele says, and Rive seemed to have cut all family ties, claiming he would leave his house to his nephew instead.36 Rive left his house to Ian Rutgers, who was not a relative but the man to whom Rive was extremely close for a long, long time. Ian lived in a room in Rive’s flat and then house for many years. He was the brother of Andrew Rutgers, whom Rive had befriended when Andrew was a young student of his. Rive became very friendly with the Rutgers family. Ian regarded Rive as a mentor and even father figure and did not or could not reciprocate the physical attraction Rive felt for him. ‘Nephew’, unbeknown to Mphahlele, was not indicative of a blood relative but was, instead, often a code word used by Rive for a young man he felt close to, and to whom he might have been sexually attracted or involved with, and whose presence he had to explain away, ironically by invoking conventional familial relations.

Those of us who worked with Rive during his years as a lecturer at Hewat College remember being introduced, during suppers at his home in Windsor Park or on the sports field, to a number of his ‘nephews’ and many of us knew what that meant. In a short story that partially fictionalises my attempts to create a biography of Rive, I focus on the attempts of the character called Richard to disguise the boys he surrounds himself with, and to whom he is attracted, as ‘nephews’.37 The story questions Rive’s silence and secrecy about his sexual life and his need to disguise real relations with fictitious familial ones.38

While Rive did on occasion consciously enact what Judith Butler calls ‘parodic replays’ of heterosexual convention, at other times he used these conventions to disguise his secret life as a homosexual man.39 These heteronormative peformances can be read as symptomatic of his deep yearning to be ‘normal’ – part of conventional, mainstream social existence and, as a sporty man, to assert what Adams calls the ‘macho image’. Yet at the same time these performances by Rive can be read as poking fun at these very conventions and their language.

Rive had numerous friendships with young men, often stemming from his keen desire to help the youth, especially those who came from poor backgrounds like he did, to realise their academic or sporting talent. A number of these friendships must have been sexually charged but remained clandestine and silent; perhaps these unspoken relationships were unintentionally encoded in Writing Black where he fleetingly describes these moments of taboo friendship with ‘the local guttersnipes’ in the poetic line which is also prophetic of the despair that marked his love life: ‘We used to sit in darkened doorways, and our silence was full of the hopelessness of our lives.’40 While Rive here also notes that ‘discovery by my socially insecure family was fraught with danger’, he does not acknowledge, even in the most subtle or euphemistic way, that there might have been taboos other than crossing class lines that were implicated in his attraction to boys marginalised by conventional society.

Despite the dominant thread of deep disaffection with family, Rive certainly had moments of intimacy with certain members of his family, which he hardly mentioned and rarely wrote about in his autobiographical writings. He seemed particularly close at times to his mother, as can be gauged from the rare references to her in his work and from the accounts of close friends. Georgina was the sister with whom Richard had most contact; the character of Miriam in his novel Emergency has shades of Georgina – the sympathetic, supportive and, significantly, ‘dark’ sister who never quite gives up on Andrew, in contrast to the hostile, fair-skinned sister, Annette: ‘Miriam was easier to get on with than Annette. She was almost as dark as himself, quiet and detached. He had never really known her. She had married a bus driver when Andrew was eight and had gone to stay in Walmer Estate, seldom visiting District Six.’41 In later years, Rive visited Georgina and her husband at least once a year, and they in turn visited his Selous Court flat in Claremont where he lived for a long time. Rive wrote to Georgina on a regular basis when he travelled and Josias remembers her receiving letters from Rive when he was visiting Japan in the mid- 1980s.

One of the nieces whom Rive had time for was Georgina Retief, the daughter of the eldest of the Rive children, Joseph Rive. Retief says she was named after one of Richard’s sisters – ‘his favourite, Georgina Rive’.42 She has fond memories of her Uncle Richard, who brought her to St Mark’s Primary School in District Six and insisted she went into an English-medium class even though she was Afrikaans-speaking. He was also a student-teacher at her school, a fact she was very proud of as a young pupil. Retief also mentions that Rive stayed with Georgina and Freddie for a short while. She confirms that most of the family distanced themselves from Rive because of his homosexuality and he in turn had very little to do with them. Retief does not make any reference to colour prejudice within the family, but it is probably easier for families, in post-1994 South Africa, to admit to homophobia than to internalised racism in order to account for intra-familial hostility. The opposite seems true of Rive’s early years – it was ‘easier’ to blame the distance in his family on his ‘darkness’, rather than on his mother’s shaming affair or his homosexual ‘difference’ – both things that were much more taboo in those days than race.

As a top-performing pupil at Trafalgar Junior School, Rive was awarded a municipal scholarship at the age of twelve to fund his studies at the prestigious Trafalgar High School in the District, where he studied ‘subjects with a ring about them’ – Latin, Mathematics and Physical Science.43 Richard Dudley, a leading intellectual, educationist and member of the Teachers’ League of South Africa, remembers encountering the teenager at Trafalgar. Dudley was doing research at the school in 1944 when Rive was fourteen and in Standard 7: ‘[The young Rive was] an earnest, bustling, bright young lad, as yet unsure of himself … Among a group of really gifted pupils, he was one who drew attention to himself.’44 Dudley here shows glimpses of the larger-than-life character that Rive was to become – articulate, sharp-tongued, with an impish sense of humour.

There are disappointingly few details about Rive’s school days at Trafalgar High, where he matriculated in 1947. The only mention of the school that played a seminal role in developing his thought and politics is in a chapter of Writing Black called ‘Growing Up’:

Much of what I wanted to know about myself I later found out in books written by people who were able to articulate their experiences better than I ever could. From my primary school days at St Marks and Trafalgar Junior I read avidly and indiscriminately anything I could lay my eyes on. By the time I was at Trafalgar High my reading was partially to escape from the realities of the deprivation surrounding me.45

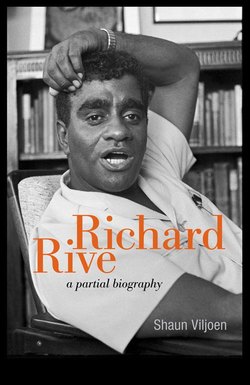

In the photograph from his high school days, Rive appears reticent, reserved, almost shy, hands just touching the shoulders of his classmate kneeling in front of him. Kneeling just to the left of Rive, in the centre, is my father, Ian Viljoen. This was the most uncanny moment of my research into Rive’s life. It was only sometime after I came across this photograph that I recognised my father. I had no idea he had been in the same class as Rive and he had died long before I embarked on this research. Julia Williams, the young woman kneeling on the far left, married Ivan Abrahams, who was a fellow student with Rive at Hewat College and later a colleague at the college (it was she who helped to compile information about this photograph in June 2012). Abu Desai, standing on the far right, became vice-rector at Hewat College while Rive lectured there. (How segregation and apartheid created these intimately connected colour-coded villages within the city!) The mathematics teacher, Mr Roux, stands at the centre.

Richard Rive (back row, fifth from the right) with some of his Standard 10 classmates at Trafalgar High in 1947 (photographer: unknown) Reprinted by permission of UCT Libraries (BC1309: Richard Rive Papers. A3. Photograph of the matric class of Trafalgar High, 1947)

Rive’s high school years coincided with the reign and fall of Nazism and the renewed vigour of worldwide debate about freedom, equality, democracy and national independence. His years at Trafalgar High were to be formative intellectually and ideologically. Dudley captures the decisive intellectual influence the school had on Rive’s outlook on life:

At Trafalgar a climate and ethos had been created which was unequalled in any institution for the oppressed at that time. For among the teachers were distinguished scholars like Ben Kies, Jack Meltzer, Suleiman (Solly) Idros, George Meisenheimer, Cynthia Fischer and the equally distinguished science teacher, H.N. Pienaar. This generation of teachers … were the articulate bearers of a new outlook in education, a team dedicated to excellence and selfless in their service to their pupils … It is here where the teachers brought into the classroom, from all corners of the world … writers and their works to [nurture] the minds of their pupils … Th rough these teachers … these scholars learnt that oppression was created by mankind, could be ended by mankind, and that a new society could be created too by mankind.46

Many of the teachers Dudley refers to were part of an intellectual tradition coming out of the left-wing reading and discussion circles and broad social movements in South Africa at the time.

Ben Kies was the most influential of these scholars and teachers at Trafalgar High. He was regarded as the leader among the Non-European Unity Movement (NEUM) leadership. His tall and sturdy bearing complemented his incisive intelligence, encyclopedic knowledge and frank, forthright manner. Kies was part of the leadership that propagated the notion of a principled, programmatic struggle propounded by the All African Convention (AAC) and its constituent organisations, formed in 1936, and later by the NEUM, formed in 1943. Both these organisations propagated a struggle against racial oppression and economic domination on the basis of a minimum programme of demands, aimed at breaking with the dependence on ruling-class concessions that was the premise of the nationalist politics of negotiation adopted by the ANC at the time. These more radical intellectuals saw the limitations of narrow nationalism and were inspired by the ideals of the French and Russian revolutions, by the works of Marx, Lenin and Trotsky and by the ideas stemming from the internationalist, anti-colonial movement emerging from the period after the Bolshevik revolution. The NEUM, a broad front of civic and political organisations, reached the peak of its popularity in the late forties and early fifties but then fragmented and was eclipsed by the more popular ANC and later Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC). The ideology of the NEUM, however, remained influential in the 1950s and beyond and was marked by subscription to a radical anti-imperialist internationalism and to a policy of ‘non-racialism’. Non-racialism challenged the existence of the category of ‘race’ and insisted on a common humanity of all people and on a definition of national identity that stressed common interests rather than differences among South Africans. This particular conceptualisation of non-racialism was to be at the heart of Rive’s work as a teacher, sports activist and writer. Ironically, while Rive revered him as a teacher and an intellectual, Kies was later disparaging of Rive’s character and dismissive of his creative work. In the mid-1970s, Kies told me that he felt that Rive tended to be an opportunist and a poseur and that his work was trite and reinforced stereotypes.

The far-reaching ideas seeded during his high school years were further developed when Rive went to study at Hewat Teacher Training College on the Cape Flats after high school and then again during his years as a teacher at South Peninsula High School in the southern suburbs of Cape Town, where a number of his colleagues were NEUM intellectuals. Later in his career, as lecturer and eventually senior lecturer and head of the English department at Hewat College, he was also among colleagues who were leading and active members of the Teachers’ League of South Africa. At South Peninsula, Rive made his mark as an English and Latin teacher. Th rough his friendship with fellow Latin and Mathematics teacher Daphne Wessels, Rive became a very close friend to Daphne’s husband, Victor Wessels. It was largely through Wessels, but later also under the influence of prominent NEUM members such as Ivan Abrahams, a colleague at Hewat College during the 1970s and 1980s, and Harry Hendricks, with whom Rive worked in the Western Province Senior School Sports Union and in the South African Council on Sport, that Rive consolidated and refined the intellectual leitmotifs of his life – commitment to the underdog, non-racialism, progressive nationalism, principled struggle, universal equality. While ‘Rive never publicly belonged to any national liberation organisation in South Africa’,47 he was a product of, and consciously aligned himself to, the ideological positions of his political teachers and mentors in the NEUM. For most of his adult life, Rive was at one time or another a founding or leading member of civic organisations such as school-level and national sports bodies.

In a letter of 30 July 1954, Rive, a highly articulate and well-read twenty-four-year-old teacher at South Peninsula High, committed to the struggle and to the ambition of becoming a writer, describes to Langston Hughes, in the understandably overblown terms of a wide-eyed and overawed young writer in the making, himself and his political ideas:

… [I] am avidly fond of reading and fanatical about politics.

I belong to a school of thought, Trotskyite and Leftist in its outlook (shades of Senator McCarthy) who believe in non-collaboration as a political weapon. After becoming a gold-chorded [sic] King Scout in the Boy Scout Movement I was almost forced out because of speeches and reports attacking Imperialistic indoctrination and the division of the movement on racial lines. I’m out of it now.48

While at school, Rive joined the Scouts movement rather than the church brigade, as the family thought the former more respectable than membership of the church lads’ brigade, which entailed ‘marching through the streets behind a blaring, tinny band’.49 It was while he was in the Second Cape Town Boys’ Scout Troop that Rive first met artist Peter Clarke, who was to become a good friend and fellow writer. Rive’s already developed sense of the iniquities of racialism and his courage to speak out against injustice, which he relates to Hughes, were hallmarks of his outlook and character even in these early years. In slightly later correspondence with Hughes, Rive gives more revealing detail about the incident in the Scouts:

Concerning the Boy Scouts, in South Africa it is divided into racialistic groups. When Lord Rowallen, chief scout of the world, visited South Africa, a preliminary meeting of Scouts was called to ‘decide on the questions he was to be asked’. People started asking silly questions like official length of garter-tabs and colours of scarves. Everyone shirked the political issue till I asked ‘whether the division of Scouts into racialistic groups as practised in South Africa was in accordance with true Scouting principle and tradition’! Complete chaos. When we met Rowallen I asked the same questions and of course things were made so hot for me that I resigned. My troop threatened to resign in protest. But I objected.50

We glimpse in this letter, in both the actual event recalled as well as in the rhetorical representation of himself in the narrative, with its evident sense of rhythm, drama and climax, the fearless, outspoken leader of the troop, the irrepressible and just voice of a leader of the silent, oppressed masses. The young Rive is keenly, even boastingly aware of the transgressive nature of his ideas, of his talent for words and courage to speak out, and of his ability to play leader.

His fearless breaking of the silence on racial issues must have been spurred on by his own experiences of racist attitudes because of his dark skin. While the progressive teachers at Trafalgar High were to help him formulate his non-racialism, there were others whose bigotry must have wounded him deeply. Gilbert Reines, who was a fellow pupil at Trafalgar and later the husband of Rive’s primary school teacher Ursula Reines, remembers one such Standard 6 teacher they had at the school:

You know, in those days, you had to bring your mug to school to receive milk, and if you’ve forgotten it, [this teacher] used to put a saucer on the floor with milk in it, and make you lick it, you know, lap it up like, like a cat … And … he always tried to catch Richard out, I think, for something or other. But one day … he said to Richard very seriously, ‘Oh d’jys ʼn slim kaffir’ [‘Oh, you’re a clever kaffir’].51

In the classroom, on the sports field, inside the home – wherever he turned, it must have seemed to the young Richard Rive, he was being assaulted by soul-destroying hatred based on the colour of his skin.

Besides highlighting the racial situation of the time of his childhood, the early chapters in Writing Black focus on two other areas of his youth so fundamental to Rive’s whole life – sport and his ambition to be a writer. Even at an early age, Rive was a superb athlete (as he revelled in recounting when he was an older, rotund and quite out-of-shape man), winning prizes at amateur competitions organised by the well-meaning social workers in District Six. Peter Meyer, a long-standing colleague in the sporting world and fellow educationist, traces Rive’s development as a sportsman:

His interest in athletics started at primary school and developed under the guidance of physical education teacher ‘Lightning’ Smith at Trafalgar High School … He excelled particularly in the four-hundred-yards hurdles … and the high jump. During the late 1940s he became the South African champion in these events, participating in the colours of the Western Province Amateur Athletics Union and in competitions of the South African Amateur Athletics and Cycling Board of Control.52

According to Joe Schaffers, Smith was a well-known wrestler and a member of the ‘exclusive, upper-class “Coloured”’ Aerial Athletics Club, which Rive also joined. Even his earliest aspirations of developing his talent as a sportsman were frustrated by the politics of racism and prejudice: ‘At first the members, all fair-skinned, were worried about my dark complexion, but relented because not only was I a mere junior but I attended Trafalgar High School.’53 This attitude, which tempers overt racism with overlays of class considerations, encountered by Rive early on in life, surely increased his determination to get the best education he could and, in addition, to flaunt it as a retort to people judging him by the colour of his skin.

Besides his participation in organised sport, Rive was also keen on mountain hiking, often walking up the numerous tracks on Table Mountain with friends and students. The walks through the mountains above Kalk Bay and the paths up Table Mountain from the Pipe Track were favourite routes. He loved swimming and the sea, and occasionally went spear-fishing. One of his spear-fishing friends was Jim Bailey, owner of Drum magazine. Rive knew Bailey even before he made a long trip in 1955 to Johannesburg to meet the staff of Drum and Es’kia Mphahlele in particular.

Every other aspect of life selected for display by Rive in Writing Black – childhood, sport, teaching, studying, travelling – is consciously and demonstratively linked to the colour question and oppression in South Africa. The autobiography is as much protest literature, or ‘anti-Jim Crow’ as he calls it, as it is memoir. In fact Writing Black grew out of a keynote paper Rive delivered at the conference of the African Literature Association of America held at the University of Indiana in Bloomington in 1979. His paper was called ‘The Ethics of an Anti-Jim Crow’ and used the story of his childhood in District Six and young adult life to emphasise the complete exclusion of people who were not white from civil society in South Africa.

In both the paper and the memoir, Rive links his drive to be a writer to his being a keen reader as a child, a connection commonly made by many other writers when recounting memories of childhood, as documented in Antonia Fraser’s edited volume The Pleasure of Reading. Rive read voraciously and indiscriminately everything he could get his hands on ‘to escape from the realities of the deprivation surrounding me’.54 He also insists on capturing the racialised assumptions about the world of books embedded in the perceptions of his young self: ‘I never questioned the fact that all the good characters, the hero figures, were White and that all the situations were White … Books were not written about people like me. Books were not written by people like me.’

The initial chapter, which covers the period between 1937 and 1955, is in fact primarily about Rive becoming a writer. It is noteworthy that a number of aspects of his childhood reading are foregrounded and conflated in his recreation of these early years. He establishes that he was a keen reader as a high school student and states that he was drawn to the classics of English literature. He names Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Scott and Haggard in particular. Rive was not only genuinely inspired by these writers, but was also consciously establishing and asserting his credentials as a cosmopolitan intellectual and writer. In addition, he has an acute awareness of how the received literary tradition was constructed and functioned as a Eurocentric way of seeing the world. The United States was not only the place of origin of Rive’s enigmatic father but also, ironically, the source of the inspiration to be an ‘African’ writer; to feel that his life, his place and his times were worthy subjects for serious literature.