Читать книгу The Polio Hole - Shelley JD Mickle - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

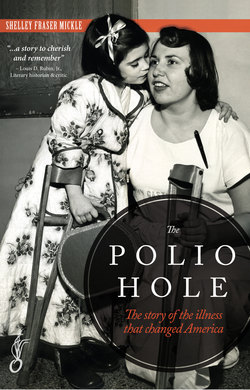

2 PARALLEL LIVES

ОглавлениеThat year, I am among 33,267 falling down the Polio Hole. But I do not know this. I am six; I still think a woman called the Tooth Fairy comes at night to buy my baby teeth, when they fall out. I have heard the word epidemic, and I now have a sneaking suspicion I am in one. But what else I do not know could stretch across the outfield at Yankee Stadium.

I do not know that the virus that has attacked me is as old as Moses. I do not know of the stone found in Egypt, 2000 years old, with a picture etched on it of a boy with a withered leg. I do not know the virus has lain underground, mostly asleep for thousands of years, claiming few, but awakening now with a vengeance that no one understands, but, in time, will puzzle out: in our heavily industrialized nation, our ability to disinfect almost everything has brought rewards and problems. Babies have a smaller chance of “catching” the poliovirus earlier in life when the infection is mild and when maternal antibodies provide temporary protection. Therefore, infants are not immunizing themselves with a mild case when the virus is no stronger than a cold. Infantile paralysis—its name was once apt, but now infants are no longer its only prey.

An old virus has awakened and is sweeping across America.

In fact, in August of 1921, when Franklin Roosevelt, who would become the 32nd President of the United States, contracted the illness, doctors suspected the virus was changing—searching out older victims. For the next twenty years, what was known about the illness could have been written on the back of an envelope. About all doctors knew for sure was that it was a virus and, therefore, impervious to the miracle antibiotics, penicillin, and sulfa. Now in the 1950s it has become a national nightmare—not because it kills great numbers of children, but because its effects are so hideous. Paralyzed children can be seen everywhere.

Now I am one of the ones tonsil-free who, mysteriously by being so, fall in greater numbers down the Hole. To get it absolutely right, the poliomyelitis virus makes lesions in the gray matter of the spinal cord and brain stem, attacking the neurons of the spinal cord, affecting nerves that go to muscles of arms and legs but, unlike spinal cord injuries, leave touch and all other sensations. Or, the virus goes to the brain and nerves of the upper body, grabbing hold of breathing and swallowing. For years, no one even knew how someone “caught” it. What was its portal of entry? The mouth? The nose? How was it passed from child to child? Why did it come in the hottest months? Why did boys seem to get it more often than girls?

Rumors spread: Flies carry it. It lives in the toilet. It’s carried in water. Close all the swimming pools. Shut down the movie houses. Stop holding hands. Stop using library books. Spray all the mosquitoes. And, why in the ever-loving world couldn’t someone stop it?

In the 1930s, some tried. A vaccine was crudely made. But because a virus cannot live outside of a body, researchers began injecting the virus into the nervous system of monkeys and letting it grow there, then killing the monkeys and grinding up their nerve tissue to use in a vaccine. No one knew that nerve tissue from an animal injected into a human causes encephalomyelitis—a deadly inflammation of the brain and spinal cord. The results were disastrous.

Later, researchers tried a live-virus vaccine, inactivating it with chemicals and supposedly leaving just enough to give a mild form of the illness; but when they used it on children, the results were equally catastrophic. Some died; others were left paralyzed. Simply, no one understood enough about the poliovirus to prevent it, and the hope for a vaccine began to fade.

Now in 1950, when the virus gets me, hopes for a vaccine have revived. But, which one? In Pennsylvania, Dr. Jonas Salk believes in a dead-virus vaccine that will contain just enough of an inactivated virus to trick the body into thinking it has already had the illness, should it try to invade again. But, how to kill the virus effectively? How to grow it to harvest for a vaccine if not in an animal’s nerve tissue? And, can it be used in the bloodstream?

This last question is especially puzzling, for the virus did not seem to have a viremic phase, which would make a vaccine useless, since the bloodstream is where the polio battle must be waged. It is there where antibodies are built in the lymph system, then secreted into the bloodstream to attack an invading virus. Instead, the poliovirus seemed to bypass the bloodstream and go straight to the nervous system to do its dirty work, paralyzing muscles, sometimes even the ones that breathe. At the Polio Unit at Yale University, Dr. Dorothy Horstmann is working on just this crucial part of the puzzle.

In Ohio, Dr. Albert Sabin argues that only a live-virus vaccine will have the potency to build long-term immunity to prevent epidemics altogether. In Maryland at Johns Hopkins University, Dr. Isabel Morgan has just walked out of her lab and shut the door. Being a woman in the hard world of science has been too difficult; she hungers for a different lifestyle. But as she walks away, she leaves a blueprint that, in time, Dr. Salk will pick up, and, in it, find possibilities. She has been successfully killing the virus by using formaldehyde, then inoculating monkeys with it and finding none are getting sick.

Salk, Sabin, Horstmann, and I—and, yes, even the one hundred thousand monkeys that will become the unsung heroes in the fifty-year search for a cure—are all leading parallel lives. Yet, we are living the same story.

•

I wake up and am moved downstairs into a ward. As the nurse wheels me on a stretcher past the monster iron lung machine, I see it so closely that I have to shut my eyes. But I have escaped it. It has not had to be turned on, even though in each foot the virus-vine has stolen muscles. I am as stiff as a child made out of fence wire. Nothing on me will bend, but I can breathe and swallow. The virus-vine has now backed off and run on to find someone else to be its host.

The room seems so large. Beds with rails are against walls, and mine is pushed beside a big window that looks out onto the hospital lawn. There is nothing to see there except grass and trees and a bench where visitors, when they come, can sit. My mother and grandmother are not allowed inside this part of the Isolation Hospital where I am now. They have gone home; but before they left, my mother told me she would be back tomorrow. She has found a room in a boarding house where she can stay.

The nurses change from day to night and then to day again. There are morning sounds in the hall, the tinkling of carts, the sound of footsteps. I sit up, my legs twisted under me in an odd way, because if I fold them this way, I can sit up. Then the room floods with men in white coats. Doctors, making rounds, circle my bed. They marvel at the way I have discovered to bend myself so I can sit up. “Look at this! Oh, my!” Sounds of celebration float across the ward; but then, one of them says, “Don’t do this anymore. It might make you worse.”

I lie down, and a board is put at the foot of my bed. “Push against this,” one says. “Keep your feet flat against this,” they all say. Keep your feet against the board. Hold them there. Sleep, eat, stay with your feet against the board. It will help them to stay straight.

Never in all of my life have I slept on my back. I want to be good, but I see no real use in this. The white coats walk out; the ward is now a sound of rattling breakfast trays. What can I do lying flat with my feet up against a board, especially when they are like cold taffy, twisted in odd shapes that cannot be straightened?

Now an urgent need pounds in my head. Back when I was four and had my tonsils out, my mother gave me half a cup of coffee mixed with milk to soothe my throat. And I drank so much that now I can’t seem to do without it. I’m the only kid in first grade who has to have a cup before doing math, opening a reader, or even answering the roll. If I can have a cup of coffee, I might make it through this. But then, the breakfast cart rattles next to my bed, and “Coffee please,” I say, which only makes the nurse laugh. “Coffee isn’t for children.”

Now I have a full-blown headache from caffeine withdrawal. I’m as unbendable as a coat rack. Sneaking a sit-up, I find only a ward full of children whom I cannot see. They are bodies in beds pushed against the walls. I have the torture-board at my feet and am chided for sleeping on my stomach.

When lunch comes, I know I am in real trouble. I ask for ketchup, and the nurse plops one little circle about the size of a quarter on my plate. At home, I poured ketchup on everything, at every meal. My grandfather laughed at my popping the bottom of the ketchup bottle to deliver a glob onto mashed potatoes, green beans, yellow squash, even Jell-O. “That’s enough. Stop now.” But I kept going, dousing peas, lettuce, carrots, bread. I could rattle my family, and yet, they could not think of a good reason for not letting me do it. My ketchup bottle became a symbol: me versus the ways of the world. Now, here, I desperately need my own bottle, gun-slinger close.

As the nurse walks by, she is writing on a clipboard, and I call out, “Can I have paper? And a pencil? Please?”

I have to get a message out to my mother.