Читать книгу The Polio Hole - Shelley JD Mickle - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

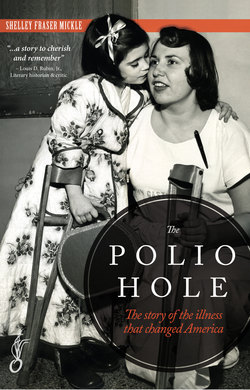

5 MY NIGHT VISITOR

ОглавлениеI am no longer contagious. It’s been a few weeks. I am safe now for anyone to be around, but I am weak; muscles have been robbed. The nurse says I have to stay here until I am strong enough to go home. Boy! That’s the pits. And what about the coffee and ketchup? But I know better than to ask. I know, too, my mother is working on it.

I am moved upstairs to a small room. This is the children’s section. The adults are all somewhere else. Farther down the hall, children the color of Verna Mae stay in rooms of their own. My new room is next to a large ward where young children live in iron lungs. The virus is finished with them, but they still cannot breathe on their own.

My mother walks into my new room. Her auburn hair, lightened to the shade of a ripening tomato, is carefully fixed. The freckles that decorate her skin look as if a cinnamon bottle has been shaken over her. She carries a whopping big bottle of Heinz Ketchup and a thermos of hot coffee. She laughs. She sets the ketchup on the table beside my bed, pours me a cup of coffee in the thermos lid, and then hands me a Sears Catalog and Zip.

Zip! My strange little stuffed toy with rubber hands: good to sleep with, good to punch when I am mad, good to whisper secrets to, good for listening to my singing with nary a word of complaint. In one of his hands is a rubber banana, ready for me to pop into his smiling mouth.

My mother stays with me through the afternoon. On other days during her visit, she wheels me into the iron-lung room to visit.

The sound of the machines is enough to make me think I am in a horror film. Heads stick out, surrounded by rubber collars. Portholes, like on a ship, are what the nurses open to reach the bodies of the kids. And there is that constant hiss.

My mother and I make friends there. A young boy, four, in his iron lung that is three times longer than he is, is a budding artist. He cannot breathe on his own, but with his mother’s and the nurses’ help, he can scribble a picture with crayons inside the iron lung and send it out.

He makes pictures to give to me every week. We swap our handiwork, and our mothers become friends, too, sometimes even going together down to the cafeteria for coffee and a smoke.

One week no picture comes. I ask my mother, as she sits beside my bed, “Where is it?” I mean his art work. “Will you go see?”

But she doesn’t get up. She fiddles with her purse. She pulls out a handkerchief. The boy has left, she tells me. He has gone home. He is no longer here.

I get the itchy feeling she is not being straight with me. She is lying. She covers her eyes. I hear the sound of her crying; then finally, she whispers the truth.

Dead? How? He was only four. He drew great pictures. He used a lot of red; there were sometimes even red trees and red cats and red airplanes and red fish. And then the thought comes: Where am I, exactly? What does all this have to do with me? I think I know. But I need it named.

I don’t ask my mother. I know she’s not up to it; besides, visiting time is almost over. When the night nurse brings my supper, I decide she’s the one. I watch her bustling around, putting the rattling tray down and pushing it near my bed.

“What is wrong with me?” I ask, but she pretends she does not hear. She is silent. She doesn’t move. Her eyes fill with tears. “Why am I here?” She ducks her head and rushes from the room.

For some time I’ve known that what I cry over is rarely what makes an adult cry; yet, my curiosity is raised to a whole new level. I’m now ready to pick on someone else. But the nurses are careful. They are quick and bubbly when they walk into my room, which doesn’t give me a chance to ask anything. Maybe the word has spread that I’m getting nosy. I’m also certainly lonely. After all, I’m here in a room all by myself where the hours are endlessly flat. TV’s not even known yet. And no radio— nothing but walls, a few toys, and the torture board at my feet.

At night I hear carts rolling down the hall, and outside, cars moving with engine noises and an occasional squeal of brakes. The glass at the window is a black mirror, giving back to me a horror snapshot of myself in a hospital bed as high off the floor as a table. Then, unannounced, a nurse rolls a stretcher into my room. “Thought you might want a visitor.” The nurse pushes a girl next to my bed.

I look over at her. She is obviously older than I am. About twelve, I guess. Her eyes flicker over at me and then stare back up at the ceiling. Nothing on her can move.

The nurse says my night visitor is being weaned from the dreaded pumping machine. Every few hours, she is taken out to let her lungs work on their own. Supposedly her lungs are being built up to an all-day outing. The nurse turns my visitor’s head on the pillow so she can comfortably see me.

We stare at each other. Her skin is black, and the strangeness of this sits in front of both of us. Our world outside would work at every turn to separate us, but no one here is saying anything about any of that. Here, the ways of our outside world are as withered as the parts of us the virus has killed. At home, Jim Crow laws would make her go to a school separate from me. At the movie theater, she’d sit upstairs while I sit downstairs. Even the candy counter would separate us with its two sides–the back for her, the front for me. And in a bus, she would never be allowed to ride in the front with me, nor drink from the same water fountain. Outside this room, we’d be kept apart as surely as the cotton gin separates white fiber from the hull. To me, none of this has ever made sense; but now, it seems especially dumb.

The nurse leaves the room. I’m scared. Will we be all right? What if she stops breathing? Will I have to fix her? This is all so strange.

“That your paper doll?” Her voice is like somebody’s with a cold. I giggle. She smiles. Her eyes follow me as I walk my paper dolls across our beds and then set Zip on my shoulder. I give him a voice, like a ventriloquist. I try not to move my lips, but I’m mostly talking out of one side of my mouth.

I hop Zip back and forth from my stomach to hers, then ask, “What do you think is wrong with us?”

“Polio. We both have it.” Quickly she says it, as if she does not have to think.

The word fills the room like a marble dropping on the tile floor, cold and hard. Then I remember where I first heard it, the year before when I was five. It was soon after my family moved to Hot Springs, Arkansas, where often we’d go downtown to buy an ice cream or go to a movie on the main street. And there, on the undulating sidewalk, going up and down hills, past the bath houses, filled with the hot water from the springs that give the town its name, was a child. Every once in a while, a child, walking past, holding onto the arm of his or her mother. Going slow, working hard. Steel braces down their legs, sometimes crutches on their arms like sticks. They were of different sizes, different ages, almost always bigger than I. The steel of their braces was silver, yet came off as heavy dark lines wired to their bodies, like dolls mounted on displays. They moved like snails. They did not seem happy. They were bumbling.

You could always see them coming, working hard to get up the hills. Probably their families brought them for the hot springs baths. And I was afraid of them. My mother explained they’d had polio, which I had to think hard to pronounce. A disease that came to them on a germ and took them over and left them wearing the steel things on their legs like new clothes. It was a hand, I decided, that reached up from an underworld to choose certain children to wall off into its world. It was like a land in a story. It was a hole one fell into and then slid down, like the one in Alice in Wonderland, or like the funnel hole that Dorothy flew through to the Land of Oz. Yet no one ever came back from this world whole. They all returned marked.

After these children passed, I glanced back at them. I did not want to get close. I learned the name for what had made them the way they were and then dismissed it. I thought of what had happened to them as the dark side in a story that careened and sped to what was bound to be a satisfying end. All stories had dark sides, hard struggle, and then satisfying ends.

I skipped down the street in my white sandals. I ate ice cream in the drugstore and bought new crayons in the dimestore. I returned to our wood-sided station wagon to ride home in the third seat.

•

So. I look back at my night visitor. This is what this is.

Her eyes watch me. They are liquid and calm. It seems she has practiced knowing what she knows for a long time. The Polio Hole. Both of us have fallen into it. I am now one of them.

The thought slides down into the core of me. In an echo of sadness, it lands. No, I do not want to go through life like this. I do not want to be one of them. Yet, as I look over at my visitor, it is clear. For us, this is not a choice.

And then, I think again, So. So what? I pick up Zip. I set him against my visitor’s shoulder, and we sing, “I love you a bushel and a peck, a bushel and a peck and a hug around the neck.” We sing loudly, raucously, brilliantly, as if we are on the way to our own radio show and a gold album.

•

Ask any geologist, and he or she can tell you: The earth is made up of many layers. The core existed long before dust and lava and stone rained down on it. Currents, wind, or waves transform the surface at every turn. The new layers are to be tilled or folded; so they, too, will be changed, day by day, minute by minute, second by second, always. The surface is forever in flux. But the core stays just as it was on the first day.

We are not different from the earth. I was who I was long before I was changed into who I was to become.