Читать книгу The Polio Hole - Shelley JD Mickle - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3 THE UPSIDE - DOWN LETTER

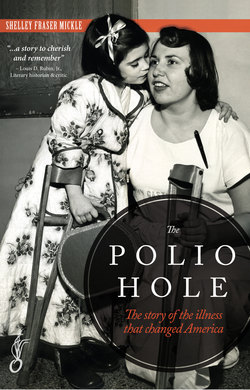

ОглавлениеAlong with baseball scores and cotton prices, the polio list appears in the newspaper every week. All those who have recently fallen to the illness are named: A boy 7, a boy 16, a boy 3, and me.

Where I am, there is no sense of time; days and nights are barely separated. My mother comes every morning to stand at the window. She waves; I wave. She dresses like a movie star in fashionable tweed suits, flat-brimmed hats, gloves, and heels. We wave again, and then she makes the shape of a banana, a glass of milk, eggs and toast, and I nod yes or no, acting out what I have had for breakfast. We are comics in full flower, mimes in everyday dress. By way of a nurse I send my message out to her: I need catchup, a big botle. Reading it, she nods, then sends back in a toy train and a hunk of mail. I hook the train up and choo-choo it around my bed. But on rounds, doctors say, “Don’t do that. Stay on your back. Move as little as possible. Keep your feet against the board.”

In the afternoon, I open the mail. Every kid in my class has sent me a homemade get-well card. They all say how sorry they are I am going to miss the Halloween shebang, and remembering this now becomes a big deal, since I’d forgotten that. I’d been nominated weeks before to be in the school-wide King and Queen Contest. I was running with Richard Key who resembles Hopalong Cassidy and can make a yo-yo do “Around the World” and “Walk the Dog.” We were going to set up collection jars all around town to collect votes. One penny was one vote. Whichever couple collected the most votes would be crowned in the school auditorium with the girl wearing an evening dress and the boy a suit and tie. There is no way I cannot admit I was hot to be the Queen.

But now my schoolmates’ letters tell me that Gloria H. has been elected to take my place. She and Richard Key will do the Halloween thing together. Maib you will nx tim, Ruth Anne B. sweetly writes on her card. There, too, unexpectedly among the mail is a letter from Verna Mae.

Verna Mae comes three times a week to our house on foot and by way of the back door. Custom in southern culture requires that she not come in the front. She stays all day, washing and ironing, snapping beans and shelling peas. Her skin is as dark as roast coffee; mine is Dairy Queen light, which has taught me my first anthropology lesson—that people can come in different colors. This fascinates me as much as my grandmother’s teeth, which click when she eats. And though I do not know it at the time— because everyone who is not a child seems old to me—Verna Mae is only twenty-seven. She looks strong, has a full, round face with bright, teasing eyes, and a voice that is like liquid warmed on the stove.

But what really strikes me about Verna Mae is the way she can tell a story. She is so good at the sound effects that you can feel your skin prickling and your eyes water. She and I have each been making up disgusting stories about ghosts slinking around in chains, dripping pus and spilling blood, and mumbling things in throaty whispers—each of us trying to scare the holy baloney out of the other. We swap our efforts, me sitting on a stool in the kitchen and Verna Mae frying up our supper.

Hold this up to a mirror is written across the top of the letter Verna Mae has sent to me.

The nurse brings me a small mirror. I put it in my hand while lying on my back, then spread out the letter on my chest. In the hand mirror, each of Verna Mae’s backward letters rights itself so I can read the words. They are simple first-grade words she must have guessed I could read.

The letter tells me what is happening at home. Not much, it turns out: a cake baked for my grandparents, a load of wash, the front yard being raked, I am missed. Then she adds a riddle, How can you tell if an elephant is in bed with you?

I turn her letter, holding it up to the mirror again to read the answer, written backwards and upside down on the bottom of the note. You smell the peanuts on its breath. I smile. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything so clever. It occurs to me, too, what a long time it took for her to write it this way. And, she wouldn’t have gone to this much trouble unless I needed it.

When the nurse comes to straighten my bed and take my temperature, I look up into her face. I study the way her eyes will not meet mine. There, yes, I see it. How do you know that something very serious is happening to you? You see it in the faces of those who take care of you.

•

But what I do not know is what this serious thing is doing to America. I do not know that since the birth of our country, American medical schools have focused on turning out bedside physicians. Break-through medical discoveries were the pride of Europe, where basic research was encouraged. France, in particular, became renowned for discovering cures for horrible diseases. But in America, it was not until John D. Rockefeller’s three-year-old grandson was dying of scarlet fever—which had no known treatment or cure—that the value of research was made indelibly clear. Rockefeller offered a physician half a million dollars to save his grandson and then poured his grief into opening the first private research institute in the country. Now polio, another untreatable illness, was driving thousands of parents to insist on finding a cure.

On the counters of stores, I had seen cards with dimes fitted into slots. I had been in plenty of movies when the lights had come up and the plate passed for the March of Dimes. But what I do not know is how, for the first time in American history, citizens are banding together—everyday, ordinary people, not the government, not private, wealthy individuals, but instead mothers and fathers of regular kids like me—to go door-to-door, calling on neighbors, collecting the means to fund a cure. This time, ordinary citizens are funding scientists to solve the mysteries. The poliovirus is changing America.

Mysteries—such as in an epidemic in Connecticut, in l943, when a nine-year-old girl who is barely sick comes into the hospital. Dr. Dorothy Horstman, curious about her, finds— much to her astonishment—evidence of the poliovirus in the girl’s bloodstream. So, over the next seven years, Dr. Horstman conducts research on chimpanzees, figuring out, finally, that doctors have simply been looking for the virus in the bloodstream too late. Its viremic phase exists only before physical symptoms appear. Now one of the most important parts of the polio puzzle has been solved, meaning the possibility of making a vaccine is, indeed, more than a hunch. And the search for one takes on the feel of a race.

•

In studies of childhood it is said that the years of six to twelve are Latency—a period of supposed calm when the base instincts of early childhood are under control so the child is pronounced educable and sent to school. It is the time when fantasy and dreams are weapons to undo humiliations and hard knocks. Deprive a child of his fantasies and dreams, and he is forever stunted. The business of six to twelve is to latch onto the idea of who we will become: Indian, Cowboy, Gangster, Thief, Fireman, Housewife, Movie Star, Chief. Supposedly symbols shepherd our sanity. It is the symbols in our stories that thread our lives together so the fabric can hold. My mind was holding onto its symbols like a modern-day fist wrapped around a credit card.

•

My father comes to stand outside the window of the ward. Dressed in a tan suit and wearing a hat like a leading man in a movie, he smiles and waves. His teeth are as white as an unmailed envelope. He hates what is happening to me. He’d rather stay home, tending to my brother. And from now on, he mostly will. I know that if I ask him to slip in to me a bottle of ketchup, he will. And he’d never say a word about it, either.

He is a typical father of the 1950s—as solid as a rock, as silent as granite.