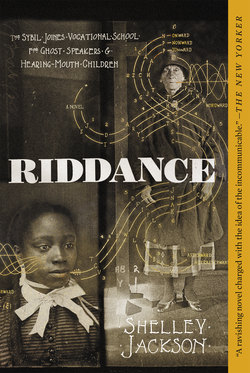

Читать книгу Riddance - Shelley Jackson - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEditor’s Introduction

I owe my discovery of the Sybil Joines Vocational School to a bookstore and a ghost.

Afternoon in a then-unfamiliar city, some years ago—heavy, overcast sky—the almost continuous grumble of distant thunder. I was in town for an academic conference, but had slipped out of the warren of little rooms in the ugly and prematurely dilapidated “new building” where the conference was being held and walked rapidly off campus into the deserted streets of the business district, feeling a little guilty about missing my colleague’s presentation, but unable to stand a moment more of our special brand of fatheadedness.

It was one of those melancholy downtowns not meant for walking, where the buildings take up whole blocks and there is nothing to be seen from street level except the stray sheet of paper listlessly turning itself over and over, or a street sign that suddenly starts vibrating and then as suddenly stops. It was with relief that I turned onto a block of small shops, though they were unprepossessing enough: a shuttered cigar store, a bodega in which an exhausted-looking man in a stained polo shirt consented to sell me a bottle of warmish water, and an unlit bookstore whose door yielded to an experimental push, revealing dark narrow aisles between leaning shelves, blocked here and there by jumbled landslides of books among which were many comfortable little hollows furry with what was probably cat hair—the place had an animal smell. A ragged floral towel curtained a doorway into the back of the shop, where something bumped and rustled.

I stooped to pluck out a book from a tightly packed bottom shelf, then withdrew my hand with a cry. A bead of blood was forming on the back of my finger. The impression that one of the books had bit me faded as the scrabbling sounds of a retreat made itself heard in the lower reaches of the shelves: the cat, no doubt, surprised in one of its hideaways. I stooped again and hooked a finger in the cloth binding at the top of the spine; the volume was stuck fast; I pulled harder and jerked it out, along with a neighboring book and a thin pamphlet, but felt the binding rip under my finger; guiltily I shoved it back in without looking at it, but had to get to my knees to retrieve the pamphlet (a 1950s-era educational brochure on hydroelectric dams) and the other book (an elocution handbook from the 1910s or ’20s), which had fallen open to a page where a newspaper clipping must have been used as a bookmark, printing the pages it was pressed between with its phantom image. Ghosting, it is called in the rare-book business, and that is apt, for this image was only the first of the ghosts that from this moment on would throng to me.

The clipping itself had slipped out. I looked for it, found it, brown and brittle with age, under my own knee, replaced it against its fainter double, and only then saw what it was.

Shocking Murder Latest Death at School for Stammerers

The Cheesehill, Massachusetts, school for stammerers that has been so much in the news lately can add another death to its grim tally, and this time the verdict is murder.

It is our unpleasant duty to report the discovery of a charred body on the grounds of the Sybil Joines Vocational School for Ghost Speakers & Hearing-Mouth Children, recently in the news for the accidental death of a student, the second this year. The victim has been tentatively identified as Regional School Inspector Edward Pacificus Edwards, who had been reported missing the previous night after his duties took him to the Vocational School, his vehicle having been discovered empty some hours after he had been believed to have gone home. An autopsy confirmed the police detective’s opinion that the victim was already dead when immolated, having been struck with a blunt object from behind with enough force to stave in the skull. Observing no particular abundance of blood near the site, the police detective gave his opinion that the fatal blow was struck elsewhere, the body having been transported at some point during the night to this low-lying and densely wooded part of the school grounds and there set alight. The clothes and personal effects of the victim were presumably consumed by the fire. A bottle of paraffin was found beside the body.

To add to the macabre circumstances surrounding this grisly find, the Headmistress of the school, Miss Sybil Joines, was discovered deceased of natural causes in the early morning hours of the night in question. A representative of the school, Jane Grandison, stenographer, denied any knowledge of the Regional School Inspector’s whereabouts after about 4 p.m. when he left the Headmistress’s office to conduct a final inspection of the grounds.

Her offer to attempt to contact the deceased, employing the method of spirit communication taught at the school, was declined by the authorities, who called it a “tasteless publicity stunt.”

The student who discovered the body was not available for interview but we have learned that her mother has withdrawn her from enrollment at the school, citing extreme emotional distress.

The police are interested in questioning a drifter seen loitering around the grounds earlier in the week.

I read, then reread the clipping, from which little polygonal shards kept drifting down to settle in the nap of the stained and smelly carpet. I had never heard of the Sybil Joines Vocational School. That alone would have pricked my curiosity, since I had flattered myself that I knew quite everything there was to know about the spiritualist movement in late nineteenth- to early twentieth-century America. But my discovery also resonated with another of my research interests, the proliferation and popularization of what one might call speech studies: stuttering “cures”; elocution; orthoëpy; Major Beniowski’s “anti-absurd” or “phrenotypic” orthography (it luks lyk this), Pitman and Gregg shorthand, and other methods of supplanting the arbitrary signs of written language with a sort of “score” based on the sounds of speech. I am only human: the murder intrigued me too. Had the mystery been solved? Suppose I could solve it?—with the methods of scholarship, of course!

I closed the book on its interesting passenger and pressed it to my chest. I had the sudden feeling that someone was looking over my shoulder: not another ghost but an up-and-coming scholar in my own discipline, slavering to take from me the “lead” that was—but for how long?—mine, all mine.

But I think I felt something more than greed, even then: the sensation that a hole had suddenly gaped in a world that had hitherto seemed decently if not prudishly buttoned up. Most of us avert our eyes when this happens, but I looked. And saw . . . A flutter of aquamarine and viridian, a pounce of stripes, a spatter of—molten ice, frozen fire—the smell of music! I express myself clumsily, and yet I believe some of you at least will know what I mean when I say that my first thought was Yesss and my second, I remember this. How indeed could I have forgotten that time I burrowed under the covers to read by flashlight past my bedtime in that warm and golden tent-cave—delicious illicitry—and then, thinking I was crawling back up toward the head of the bed, actually made my way deeper, through a tunnel that went on and on, from whose roof fine roots stretched down to fascinate my forehead, until I came up in the center of a snow-thick forest, where some mechanical angels were rehearsing a hymn of clicks and chirps before an audience of spiders? I had longed for such another opening my whole life.

I suddenly noticed a pair of eyes shining back at me from a gap in the opposite bookcase and started, dropping the book. Doubtless it was again the cat. The proprietor jerked aside the towel-curtain and stood looking at me without enthusiasm. “None of these books are at all valuable,” he said. “Please feel free to toss them around.”

“Don’t worry,” I said, “I’ll be buying this one.” He worked out the tax with bad grace and a pocket calculator, but took my money, though he watched the book vanish into my satchel with evident regret.

My subsequent researches did nothing to dispel my amazement. Even today I find myself marveling that an institution that in its heyday raised a public scandal on more than one occasion, and whose theoreticians pursued a vigorous debate with notable intellectuals of the time, should have been effectively forgotten for so many decades. The decline of the spiritualist movement explains it only in part. I believe the memory was actively repressed: If the dead do live on, the public would prefer, on the whole, not to know about it.

Once I began to look, however, I found references to the Vocational School everywhere. Other articles about the murder turned up on microfiche, and I assembled enough supporting material for a modest paper. It was well received. I began another, more substantial paper, aware that other scholars’ interest had been piqued, but confident that I had staked my claim.

It is a common occurrence, and not just among scholars, for a new obsession to awaken reverberations in the most unlikely places. Probably there is nothing really uncanny about it; the observer is newly alert to these echoes, that’s all. But it was pretty peculiar, all the same, how rapidly my archives grew. In a thrift store in Madison I found a Vocational School yearbook (containing some very interesting photographs of school activities). Walking down a street in Philadelphia, I was dealt a blow on the temple by a paper airplane that had spiraled down from some open window above me, accompanied by muffled laughter; it proved to be a page from a book about the spiritualist community Lily Dale on which the Vocational School was mentioned in passing. And in one of a number of bags of interesting old books and papers left on a New York curb, as by indiscriminate and probably illiterate housecleaners clearing an apartment whose former occupant had died, I found, tied up with twine, a sheaf of yellowing papers covered in the characters of an unfamiliar alphabet, each page numbered, dated, and labeled in a childish hand, “Betty Clamm, SJVSGSHMC”!

The Internet contains, it sometimes seems, all stories that have been and will be told. It is like that mythical Interstitial Library whose stacks readers sometimes wander in dreams, and whose itinerant librarians sometimes leave on your pillow astronomical bills for library fines levied on overdue books that you have never heard of, bills written in the already faint and soon to disappear stains of those mysterious night sweats from which you awaken terrified and out of breath. So I was not too surprised to stumble upon a reference to the Vocational School in the moribund listserv of a group of scholars whose common interest and broader topic was the work of a French philosopher whose name I did not recognize and cannot now recall but who seemed to employ a great number of obscure but wonderfully poetic terms composed of unlikely combinations or odd usages of otherwise ordinary words. I was skimming the discussion, which got quite heated, enjoying the feeling that I didn’t know what was going on, when I caught a phrase in passing: “. . . like those turn-of-the-century concerns that lined their pockets through the spiritualist fad, e.g., the SJVS.” Naturally other scholars would have come upon references to the Vocational School somewhere in their reading, just as I had. What surprised me a little more was the reference I spotted a few days later in a customer review of a pair of waterproof loafers I was considering. Well, one does not expect to find reference to obscure cultural institutions of another century (“like something an SJVS student would wear”) in the context of protective footwear! Still, they were of a conservative style and it was not really difficult to imagine a middle-aged scholar—say, one of the members of the aforementioned listserv—pulling them on and trudging off through the winter slush to his library kiosk.

That pedestrian image banished all frisson of the uncanny until a few days later, when I received a cease-and-desist letter from a party representing herself as the Headmistress of the Sybil Joines Vocational School for Ghost Speakers & Hearing-Mouth Children, and threatening legal action if I did not immediately cancel plans for an anthology of “pirated” documents produced by and about the early Vocational School, to all of which she claimed exclusive rights. Plans I had not yet confided to anyone. No—plans I had not yet made!

I suspected a prank, though I was struck in passing by certain arcane phrases and archaic usages characteristic of early Vocational School writings, and, somehow, found that my breath quickened as I read on. But when my eyes, swiftly and still scornfully descending the page, came to rest on the signature at the bottom, I thrust back my chair (scoring four claw marks in the varnish—I would lament those later) and strode into the kitchen to stare into the sink with unseeing eyes, a mad conviction growing in me that not only did the Vocational School live on, but so did that exceptional, rather dreadful, and indubitably deceased woman whose acquaintance I had made through a pile of yellowing papers, dreams, and the whispers of drainpipes and dead leaves. That the letter writer’s claims were true. Oh, not her claims to copyright, those certainly had no legal merit, but her claims to be the fourth-generation reincarnation—in the special sense of a person channeling another’s ghost—of Sybil Joines.

Of course, any halfway competent forger could reproduce the capsizing loops and botched cloverleafs of that unmistakeable signature. My conviction was not rational. Let us say that I was possessed by it.

Below the signature was a URL; I typed it into my browser and found myself regarding a plausible academic website. Vintage photograph of the Vocational School on the masthead, stock images of alleged students with pencils poised, application instructions for would-be distance learners. You may ask why I did not turn up this website in my initial research, and indeed I asked myself the same question. Later I learned that it had only just been launched; I must have been one of its first visitors. Once again I had the uncanny feeling that the SJVS was created expressly for me, was summoned forth by my interest in it, towing its history behind it like a placenta.

A couple of phone calls connected me to someone who, in a hoarse, imperious voice that crackled like an old Edison recording, identified herself as Sybil Joines. I addressed her with awed courtesy and agreed to everything she said. Placated, she eventually warmed to me. Not only did she consent to the publication of this anthology,1 but she gave me access to a great deal of immensely valuable material in the Vocational School’s own archives—much more material, in fact, than I can include here. (I hold out hope for an omnibus edition.)

A note to scholars: Any historian of the Vocational School is faced with peculiar difficulties. Its scribes and archivists alike were in agreement that a self is a mere back-formation of a voice that itself belongs to no one, or to the dead. Thus authorship would be a vexed question even if all Vocational School documents were signed, as many were not. The current headmistress of the Vocational School, for instance, derives her authority from the demonstration that she is the mouthpiece for the previous headmistress, who was the mouthpiece for the previous headmistress, and so on. In a sense, she is who she is precisely because she is not who she is, and to insist too stringently on biographical “fact” is to miss the point.

It is a fault of our age to consider all that is eccentric—and by eccentric I mean merely and precisely what lies farther than usual from a certain, conventionally defined, probably illusory center—as representing only one of two things: the symptom of a malady whose cure would restore the patient to a place in the center; or a new center, toward which all must hasten. What is true, we nearly all agree on; what we nearly all agree on must, we think, be true. But I would suggest that there are minority truths, never destined to hold sway over the imagination of the entire human race, and furthermore, ideas—less defensible, but to me, even more precious—that are neither true nor false but (I have sat here this age trying to compose a marrowsky better than fue or tralse, but hang it:) crepuscular. One might even say, fictional. Entertaining them, we feel what angels and werewolves must feel, that between human and inhuman there is an open door, and a threshold as wide as a world.

Because I am a—faintly regretful—member of the majority, and know my way back to the center, despite my excursions to its fringes, I can speak to something that interests true eccentrics not at all: the utility of the crepuscular. For no one has ever got to a new majority truth, a new center, without passing through these twilight zones and thus eccentrizing themselves.

But for every colonist there are countless expeditionists who will wander forever through deliciously ineffable sargassos, and when they write home, communicate both less and more than their correspondents would wish. For in the crespuscular every word is a marrowsky, if it is not one of those stranger compounds, those werewords, for which there is no name (word-ferns, word-worms, word-mists and -algae). What we know as meaning is not the principle cargo of such words. The Headmistress speaks this language like a native, for while the Vocational School may have appeared on county maps in the vicinity of Cheesehill, Massachusetts, its real address was in the crepuscular zone.

Because the eccentric troubles the center like a lingering dream, there has been a great deal of nonsense written in recent years about the Headmistress of the SJVS. Some have gone so far as to doubt her existence (“And quite right, too,” I can hear her say). But she did exist, was as sane as any person of original views passionately held, and whatever fugitive pains urged her on, her central motivation was and always would be the hunger for understanding. Though it is necessary to stress that for her the deepest understanding would feel like incomprehension, and would be communicable only in the way that a disease is.

So although there are mysteries to interest both philosophers and policemen in these pages, I do not propose to offer any solutions. My vision of a scholarly work with the popular appeal of a crime novel has exposed itself for the mercenary fantasy it was. The eccentric, muscled back into the white light of judgment, is just so much more center. Its value, however, is in the darkness that it radiates from the farthest reaches of the spectrum, discovering, in the black-and-white page, shades of imperial violet.

Anyone who has visited the land of the dead, in fact or fancy (and there is not as great a difference between the two as you might suppose), will have guessed that this book can be entered at any point. For less experienced travelers, I have planned a route. Its reduplicate tracks, laid down over a single evening—one by the Headmistress, one by her stenographer—will convey the reader surely, if not safely, to the end. Interspersed between these two interwoven strands, according to a strictly repeating pattern, are additional readings of a more scientific, sociological, or metaphysical nature. Those who, lacking a scholar’s interest in minutiae, want to get to the end more quickly, may wish to skip over these parts, and who knows, may even be wise to do so. But true eccentrics may find in them something—a map, a manual—that they have long been seeking.