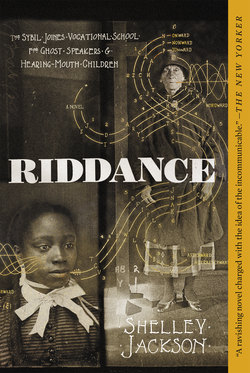

Читать книгу Riddance - Shelley Jackson - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLetters to Dead Authors, #1

In April 1919, seven months before her death, the Headmistress wrote the first of a series of letters to deceased authors. We know the date because the envelope in which it was returned, stamped undeliverable, is postmarked. It appears from her own testimony (Letter #2) that she was not initially aware that the addressee of her first letter was dead, but once this was brought home to her, she recognized the merit of the practice, and was to continue writing to him and other deceased authors until the end of her life. Dating of these subsequent letters is infuriatingly approximate, since we possess only undated copies (the originals are presumably still lost in the mail), but they seem to have appeared with increasing frequency as time went on, approaching the function of a daily journal, and providing an invaluable record both of the clouds then gathering over the Vocational School and of Joines’s declining health, mental as well as physical. She herself notes (Letter #11) that she has addressed herself to a fictional character (Letter #10), though subsequent lapses go unremarked.

Like the Final Dispatch and other materials here assembled that register the passage of time, these letters will be distributed at regular intervals throughout the volume, but readers should keep in mind that they are not contemporaneous with the Final Dispatch, but conduct us up to the point where it began.

Incidentally, there is no evidence that any of her addressees ever wrote back. —Ed.

Dear Mr. Melville,

You will not have heard of me, as I am of small account by the great world’s reckoning. Nevertheless I have made discoveries that should interest any man of imagination—and you have imagination, Mr. Melville, do you not? When I read Captain Ahab’s vow to strike through the “pasteboard mask” of visible things, I knew that I had to do with a man who had run an inky finger down the chinks in the Wall, and had wondered what wind it was that blew through it.

Mr. Melville, I have found the door in that wall.

Having caught your attention, as I hope, I will now tell you about myself.

I am a woman no longer young, tall, gaunt, with a strong brow. My dress is somber and guided by scientific principles (specifically, acoustics), not by fashion; I am no Lucy-Go-Lightly. I was born in the small town of Cheesehill, Massachusetts, and grew up odd and lonesome, since I had a stutter, and was shy to boot. Nor were my parents sympathetic, but sought, my father did, to scare my tongue straight. You may imagine what efficacy that had. Only my rabbits—

A fit of coughing has disordered my thoughts. But I was speaking of my childhood. I was an ardent reader, Mr. Melville, and one of your books concealed providently in a flowerpot eased many a desolate hour spent locked in the garden shed with the potatoes, though I do not mean to asperse the potatoes, whose company, on balance, I preferred to that of most of Cheesehill’s other inhabitants. I feel a special affinity to writers, even though, to tell the truth, it seems a silly sort of life, making up stories. While I too work with words, it is as an explorer and a scientist. Nonetheless I write to you, and not to Mr. Tesla, Mr. Roentgen, Mrs. Curie, or even Mr. Edison, for it seems to me that writers have made greater progress than scientists (myself excepted) on a venture of the highest importance to our world today, tomorrow, and yesterday: communication with the dead.

Which brings me to my point. I am the Founder and Headmistress of a boarding school and research facility, the Sybil Joines Vocational School for Ghost Speakers & Hearing-Mouth Children, where we teach children to channel the dead and, finally—though a little less finally than everyone else—to travel to their realm. My pupils are all stutterers. Why? Because stuttering, like writing, is an amateur form of necromancy.

I was myself a child when the first ghost spoke through the frozen moment in my mouth. The study of the dead became my passion. In playground games of school, I taught the other children everything I learned. As a young woman, I sought out the notable spirit mediums of the day, and eagerly applied to them for instruction, but was disappointed; if they had answers (and most of them were mountebanks), they guarded them closely. I was thrown back upon the dead, who did not fail me. I developed my own methods, and having seen firsthand the need for vocational training in the trade, resolved to found a school for spirit mediums.

Returning to Cheesehill, I poured my funds into the purchase and rehabilitation of a derelict property well suited to my needs, and with my childhood companions as talent scouts, scraped together an entering class—each and every one a stutterer like me. Their speech was broken; they were cracked vessels; I would make them perfect. Not by sealing the cracks! By sweeping away the last remaining shards. I would raise a new Eden, in which a primordial silence would rise again, and the din of human voices would no longer drown out the quiet confidences of the dead.

The first time I traveled to the land of the dead, it was an accident, and I nearly lost my life. It was also by accident that, crying out, I found my voice and with it, eventually, the way home. For to travel there one must summon up in words, not just the ground one walks upon, but even oneself, walking. My life’s work, like yours, depends on my ability to construct a convincing fiction. Indeed, I would welcome any “tips” you might have for me! But I am seeking more material help as well.

I have recently lost a student. It will happen, given the natural vivacity of children and the nature of our studies. But now my school is under seige. Philistines with no more understanding of Eternity than may be gleaned from the platitudes carved on tombstones are baying at the gates. Save the children! is their rallying cry. Rank hypocrisy, as these children are those same “stuttering imbeciles,” “degenerates,” and “mental defectives” they were so eager to pack off to any quack who promised to cure them or keep them out of sight. Emily herself (not a prepossessing child) would be amazed to hear the fanciful terms in which she is described in the press. Precious bundle? Little lamb? A big bundle, more mutton than lamb! Her doting parents’ treasure, their pearl without price? She knew exactly what she was worth to them.

But as a result of this rhetoric (for the land of the living is also shaped by words), some of our more excitable parents have already withdrawn their children from their studies, with a catastrophic loss of revenue to the school.

May I press you for a donation? Even a loan would be of signal service. I have poured the whole of my inheritance into outfitting my school and now must scrimp and scrape to buy necessities. I know your means are modest, but the need is great, the cause honorable. And one day the world will flock to my door, and then this grateful recipient of your patronage will have the wherewithal to make you very comfortable indeed.

At present, I confess, the case is otherwise. To put it baldly, I am broke.

Expecting your imminent reply, I am,

Very sincerely yours,

Miss Sybil Joines

Postscript: If you are not in the position to lend me money, could you lend me, instead, your name? A testimonial from a great man like yourself could do much to warm the frigid public eye toward this earnest Seeker.