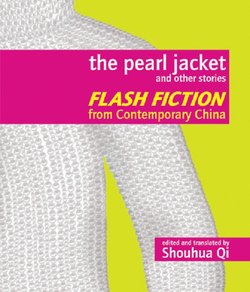

Читать книгу The Pearl Jacket and Other Stories - Shouhua Qi - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

preface

ОглавлениеFlash fiction, or wei xing xiao shuo,as it is known in Chinese literature, also goes by the name of Minute Story (yi fen zhong xiao shuo) (most likely for the amount of time required to read one); Pocket-Size Story (xiu zhen xiao shuo) or Palm-Size Story (zhang pian xiao shuo) (alluding to its small size); and, perhaps most evocatively, a Smoke-Long Story (yi dai yan xiao shuo), where one can imagine the reader taking a drag from a delicious cigarette in some smoky salon, while relishing a few lines from some make-believe world.

In the West, flash fiction can be found in the story of the boy who cried “Wolf!” on that Grecian isle over 2,600 years ago, as well as in other Aesop fables and parables. The earliest examples of Chinese flash fiction are in the remarkably “grand” creation myths of Nuwa (ca. 350 BC), Fuxi, and Pangu. The story of Pangu, for example, which first appeared in written form during the Warring States period (AD 220–63), has a word count of 350 Chinese characters.

The stories in this anthology represent the achievements in flash fiction in modern to contemporary China, that is, early 20th century to the present day. Taking root in China’s fertile native cultural soil and drawing nourishment from influences inside and outside China, flash fiction has matured as a literary form. The birth of the Microfiction Association of China in 1992, and the popularity of literary journals devoted to such fiction exclusively, e.g., Journal of Microfiction, Journal of Short-Short Story, etc., attest to the popularity of flash fiction in China in recent years. New technologies such as text messaging and blogging and extensive (though still tightly controlled) use of the internet in China make it possible for millions of people to dally with writing their own stories and “publishing” them to family, friends, and, often, complete strangers. There is instant satisfaction when the desire to be heard, and to be known, is met (“Sir, I exist!”). Imagine a nation of tens of millions of story-tellers! The future of flash fiction, it seems, is as bright and hopeful as enthusiasm (and technology) can carry it.

If writing flash fiction is exciting, translating such stories is just as so, if not more. Each of the stories in this book comes from a distinctive time and place; each has a distinctive beginning, middle, and end; each speaks with a distinctive cadence of voice; each showcases a distinctive style, whether simple, minimalist, folksy, erudite, ornate, or elegant. No two stories are alike. Therefore, instead of trying to conquer a 130,000-meter tall mountain (the approximate word count of the original stories in Chinese), I instead had to climb 130 1,000-meter high hills; each time I barely had time to utter “I came, I saw, I translated” before I had to plunge ahead again and start climbing the next hill, which, more often than not, revealed quite different topography altogether.

Among these stories are a few not so contemporary ones by the great masters of modern fiction such as Lu Xun, Lao She, Guo Morou, and Yu Dafu, all of which are exemplary in freshness of idea, depth of meaning, and intensity of feeling, as well as in execution (flow of story, character development, use of language). Other writers, such as Shen Congwen, known for his vernacular style of writing that blends the strong influence of both classical Chinese and Western literature, and Wang Meng (1934–), the writer and essayist and one of the first to experiment with the stream of consciousness technique in Chinese fiction, serve as the anchoring point for works to be written generations later. The absence of stories since the great masters (until around 1980) can be attributed to China’s turbulent history: The Great Proletariat Cultural Revolution of 1966–76 nearly wiped Chinese literature off the map. Then, in the 1980s, flash fiction re-emerged on China’s literary scene with a vengeance. Among my favorite of the stories produced since the 1980s are: “A Hawk in the Sky,” “A Serious Speech to Promote Mark Twain’s Humorous Speeches,” “White Gem,” “To Kill the Sister-in-Law,” “Precious Stone,” “Immortality,” “Straw Ring,” “Merchant of Wills,” “Concerned Departments,” “Floral Shorts,” “Mosquito Nets,” “‘Oh, Isn’t This General Manager Gao?’” “The Same River Twice?” “A Caterpillar on Your Shoulder!” and “The Outside World.” Some of these stories are traditional in their narrative mode and appear to be politically innocuous enough, but embedded in them are critical barbs no reader familiar with Chinese irony and satire will miss. In Ling Dingnian’s “Cat and Mouse Play” (2004), the historical lesson the General taught his Second-in-Command may, ostensibly, have to do with China’s distant imperial past, but the story’s political subtext, its pungent satire directed at the political life of modern China, especially what Mao Zedong did to his Long March comrades-in-arms during the Cultural Revolution, becomes apparent when one considers the fact that “Using Ancient History to Satirize the Here and Now” has been a favorite trope among Chinese writers (and dissident intellectuals) since time immemorial.

Some of the stories treat their historical source material rather playfully and give well-known, classic stories a postmodern twist with delightful, refreshing effect. Such is the case of “To Kill the Sister-in-Law” by Jia Pingwa, a writer known in the West for his Turbulence (2003), Fei Du (Defunct Capital, which was banned in China when first published in 1993), and other fictional works. Jia draws from the classic Chinese novel Water Margin (Shuihuzhuang): the story of Wu Song—the tall, handsome hero famed for having killed a fierce tiger with his bare hands—avenging the death of his ugly, midget brother poisoned by his sister-in-law Pan Jinlian (the infamous Golden Lotus) and her rakehell lover Ximen Qing. The heroic and righteous Wu Song, who had earlier rebuffed the adulterous advances of the ravishingly beautiful sister-in-law, never wavers for a second in meting out justice. Here, Jia adds a playful revisionist twist.

Whether drawing from the here and now of contemporary China or from the nation’s collective memory of its long and distant past, whether traditional, experimental, or avant-garde in their narrative modes, these and many other stories resonated with me intellectually and emotionally while I was trying to render them into English. They not only capture the pulse of life of a given time and place but also have something profound to say about the human condition, which transcends the bounds of time and place.

Of the stories featured in this book, nineteen (some of which are undated in the anthology) are from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau. These stories enrich the thematic, emotional, and stylistic tapestry of the anthology in no small ways. If I feel the “yang” force pulsing restlessly in stories from mainland China, I find myself drawn to the quiet “yin” force in these stories, pleased by their well-tuned sensitivity, ease of flow, and the satisfying yet disquieting sensation that lingers long after the reading. Stories such as “My Bride,” “Wrong Number,” “Feelings,” and “Time” read like prose poems, too. “Parrot,” the last story in this book, is fable, myth, and nightmare all in one.

The stories in this anthology tell the truth; a tall order indeed. Truth, big or small, emotional as well as intellectual, gives each story life and makes the minutes (the time it takes to finish a smoke, for example) spent by the reader a fascinating and rewarding experience.

Finally, I want to say that as a translator of these stories I have invested enough time, effort, and emotions in them to feel they have become my stories, too. Therefore, any imperfections readers may find are as much mine as the original authors’.