Читать книгу Shodo - Shozo Sato - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

Communication through writing began in ancient times with pictographs and petroglyphs, and has continued down through the ages in many forms. Ideographs developed in ancient China are still being used for communication today, through the use of brushes, pens or the latest electronic devices, in countries that use the Chinese language such as The People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, and others.

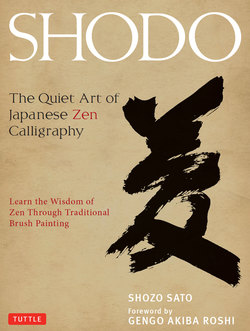

However, these same ideograms, when written with a brush under certain circumstances, are also used as artistic and philosophic expressions. This book is about how artistry and philosophy are transmitted through shodo (sho=writing; do=way), or the Japanese study of calligraphy.

Handwriting, whether used for ideogram-based languages, Roman-character based languages like English, or for any others, is uniquely individual, just as human oral expressions are. This unique expression of a human personality, which goes beyond “right” or “wrong,” is seen in the variety of examples in this book. They range from fundamentally classic to abstract, from gentle to energetic.

Ichigyo mono (ichi=one; gyo=line; mono=category) in this book refers to the one-line statements from Zen philosophy that are used in the practice of shodo. These one-line statements have mostly been taken from treatises written by Zen monks and are considered to be the “core spirit” of their works. Because the statements are such brief abstractions, however, they often appear obtuse and incomprehensible. Through the practice of writing ichigyo mono over and over again, a student may gain a greater and deeper understanding of the philosophical meaning. These statements are universal in nature and can have interpretations that go beyond the boundaries of any one religion.

Two very important phases in my life, spanning two vastly different countries, influenced the writing of this book. As a young man I lived in Kamakura, Japan, the home of many temples of the Rinzai sect of Zen, built during the Kamakura period (1185–1333 CE). Living in the vicinity of Kenchoji, Engakuji and many other famous Zen temples, I became well acquainted with their occupants, from the young monks to the abbots, who taught me much about Zen philosophy. The seeds that led to my interest in Zen philosophy thus began in those early years. When I was nineteen, I also began to take lessons in chado, “The Way of Tea,” under Kosen Kishimoto Sensei of Tokyo. I passed all the rigorous tests to obtain a certificate as Master of Tea at the young age of 21. I was able to obtain such a degree at this age because even before preschool days in early childhood, my total focus was in the arts.

In 1964, I was invited to teach in the College of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Campus. My brief was to develop a curriculum for the School of Art and Design on comparative cultures through the traditional arts of Japan. One part of the curriculum involved activities in the two-dimensional arts of sumi-e and shodo using the brush, ink and handmade paper (the first step was for the students to understand the fundamental differences between using a ballpoint pen and a brush and to observe how one line created with a brush had so much more visual impact). Another part focused on the study of Zen aesthetics through chado, “The Way of Tea.” An ichigyo mono—a hanging scroll bearing a zengo, a one-line statement from Japanese philosophy—was always on display in the tokonoma or alcove of the tea room where I met my students, and discussion on the meaning of the ichigyo mono was an integral part of each lesson. The zengo selected for display were drawn from the 1,500 official statements in Japan, but were chosen based on their relative simplicity as well as their relevance to the occasion and contemporary American life. The paradoxical nature of these enigmatic statements always led to a great deal of meaningful discussion. The wall hanging was changed each week, which necessitated a very large collection. As budgetary restrictions made the purchase of such scrolls prohibitive, I began to write suitable zengo myself. Some fifty years have passed since then, but clearly the seeds for this publication were sown in those early teaching days. I still receive letters from former students thanking me for “sharing the treasure in a moment of enlightenment” and sometimes suggesting a new meaning for a particular zengo. Over the years, Zen statements in ichigyo mono have personally given me much spiritual encouragement and helped me develop a deeper understanding of the meaning of life. It is my hope that the zengo in this book will also be a guide leading to a moment of enlightenment for readers beyond the walls of a university course. This book has been written from the viewpoint of my capacity as a tea master, where all of the arts (including the craft arts) are a part of the discipline of chado, many of them living arts such as cooking and landscape gardening.