Читать книгу Shodo - Shozo Sato - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBokki: The Spirit of the Brush

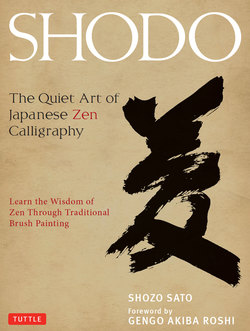

The combination of sumi (black ink) and brush used to create Chinese ideograms is called shodo or “The Way (do) of Writing (sho).” To create sho as an art form requires not only physical preparation but also mental preparation. The sho creator must learn breathing control and how to concentrate energy or ki (chi) in the lower part of the abdomen. (Since ancient times, the martial arts disciplines of Asia have required this same centering of a person’s ki energy in the lower abdomen.) The sho creator, by concentrating and internalizing energy, can then pick up the brush and in a matter of seconds execute an ideogram. But those preparations are not needed when using the same tools for writing personal letters or business documents; for those prosaic tasks one can casually pick up a brush or pen and write.

In shodo it is considered sacrilege to go back and touch up the work. Any adjustment or touch-up would be apparent, and would interrupt the ki, and therefore the created work wouldn’t be an honest representation of the artist’s energy and personality.

In the preface it was mentioned that sho exposes the personality of the writer. (This phenomenon is not limited to ideograms, of course, as handwriting analysts in the West attest.) The act of grinding sumi ink on a stone is another way of transferring human energy to the writing of an ideogram. Sumi is created by burning oils of various kinds, and the soot is collected and mixed with animal glue. Because the soot is basically carbon molecules, when a stick of sumi is ground on the suzuri (grinding stone) with water, the extensive back and forth movements create static electricity in the liquid. Sumi ink that has been ground on a suzuri thus becomes charged with human energy (similarly, recall that our nervous system conducts electric messages to the brain) and when a sho artist who is using concentrated energy writes an ideogram using this ink, it is said that the lines contain bokki (bo=black ink, sumi; [k]ki=energy).

A very significant study connecting this type of energy and its physical manifestation was done by the highly respected Tanchiu Koji Terayama, director of Hitsu Zendo. The English translation of his book’s title is Zen and the Art of Calligraphy (transl. by John Stevens; Penguin Group, 1983). In an effort to understand the importance of bokki, Terayama enlisted the assistance of scientists. He had small sections of shodo masterpieces from centuries past magnified to a value of 50,000x with an electron microscope. The researchers discovered that the carbon particles of sumi in a masterpiece showed a distinct alignment, while in a look-alike forgery of the same work, the carbon particles were instead scattered.

Down through the ages, the concentrated energy or ki of certain individuals has been transferred to their art, and that energy of the artist is called kihaku. A common expression in Japan is that “unpitsu no kihaku”: power in the movement of the brush can be permanently recorded in a brush stroke. When an artist creates a work in a state of kihaku with the use of sumi ink, that work continues to provide strong impact and emotional appeal to receptive viewers across the ages.

When you visit a museum and see ideograms on display, bokki might not necessarily be obvious at first glance. The artwork may seem to be quiet in appearance. But when ki is present in an ideogram, it will spiritually affect the viewer. Each line or dot containing the full power of bokki will impact the viewer and add to his or her understanding of the statement and the source from which it comes. For this reason, bokuseki that is written by Zen monks focuses on the beauty of the ideogram, but also endeavors to reach the viewer’s heart and soul with the power of potentially opening or expanding an individual’s realization.

Obviously, such powerful ideograms filled with “the spirit of the brush” are not written easily. Students of shodo must constantly practice the strokes in the required order using kaisho, so that writing the ideogram correctly becomes second nature. Finally, then, without striving for the perfection, form and order of the strokes, the sho artist can create an ideogram that is permeated with spiritual beauty rather than merely visual beauty. This is the ultimate goal for all sho artists.

Many years ago when I was a preteen, my sumi-e teacher took me to a museum to see historic, famous sumi-e and sho. I still remember his admonition: “In order to appreciate the work, one’s heart must be pure and receptive and then this ancient calligraphy will speak to you.” This comment was strange to a naïve young boy. Seventy years ago the understanding of how molecules and carbon electrons worked was not common knowledge; however the great artists from centuries ago must nonetheless have recognized that their power of ki did impact their work.

Look at the example on page 2, “Bokki, Spirit of the Brush” by Zakyu-An Senshō. It was written to convey the foundation of bokki. It depicts the ideogram for ichi, meaning “one.”

The Chinese Roots of Shodo

The Chinese roots of Japanese calligraphy have a long history. Some 3,500 years ago in China, the hard surfaces of animal bones, tortoise shells and stones began to be inscribed with sharp instruments to produce documents for administrative purposes or with statements or predictions from the gods. These pictograms, chiseled in the form of a script based on squares of uniform size and using a limited number of angular lines or strokes administered in a particular order, were gradually systematized into ideograms similar to Egyptian hieroglyphics. Over successive centuries, the ideograms changed and evolved, becoming more abstracted. Ideograms began to be inscribed on the smooth surfaces of bamboo, boards, animal skins and handmade cloth. Often two or three of the original simple pictographs were combined to create a new ideogram with a special meaning. These multiple combinations, in turn, led to a more complex writing system. A single ideogram composed of modified pictograms now might carry with it a new special meaning.

The traditional and contemporary kanji in use today in academic writing number some 40,000. In modern Japan, some 2,000 to 3,000 kanji are used daily in newspapers, magazines, and other general reading materials.

Around 100 CE, China began to produce paper; sumi ink became more readily available, and a new kind of soft brush was created by combining types of animal hairs. It was a milestone: the incised version of writing could be replaced by the characters formed on smooth expanses of paper, with sumi ink and a soft flexible brush. The development of this latter tool, whose flexibility allowed variations in the thickness and curve of the lines of ideograms, brought about another style of writing, one that is similar to what we commonly see today. The writer was now free to write creatively in a personalized style.

Since then, generations of Chinese court nobles, government officials, priests and literati have left a multitude of writing styles whose nuances are a unique reflection of their individual characters and personalities. These writing styles, with their special brush movements, have been collected, systematically categorized and published in encyclopedic form. This tome is still commonly referred to today in China, Korea and Japan, as a guide for students of shodo to the variety of ways of writing individual ideograms. In the book, first published in Japan in 1917 (see the Appendix for info on the 2009 edition, the “Shin Shogen”), the name of the writer and the time period is noted alongside each ideogram. This publication is a must in the library of anyone who practices shodo or other literary writing.

Calligraphy in the Chinese tradition was introduced to Japan around 600 CE where it became an essential part of the education of members of the ruling families. Royalty and the aristocracy studied the art by copying Chinese poetry in an artistic manner, developing it into a highly refined art. At the same time, a style of calligraphy that was unique to Japan emerged, primarily to deal with elements of pronunciation that could not be written with the characters borrowed from Chinese. Calligraphers in Japan still fitted the basic characters, which they called kanji, into the square shapes or block form that the Chinese had determined centuries earlier, but also developed a less technical, more cursive and freer style called hiragana and katakana (see page 16). Over the centuries, other influences came to bear on Japanese calligraphy. One was the flourishing of Zen Buddhism beginning in the Kamakura period (1185–1333 CE) and Zen calligraphy practiced by Buddhist monks. Another was the elevation of Zen calligraphy as an integral part of the tea ceremony, itself connected to Zen Buddhism, in the fifteenth century. Indeed, an essential step in the preparation for a tea ceremony is looking at a work of shodo to clear one’s mind.

The Artistry and Philosophy of Bokuseki

As with other cultural arts in Japan, learning shodo begins with copying or following the Master’s art. Schoolchildren use ideogram copybooks, while those who take shodo lessons outside of school also use these copybooks. Advanced students often obtain direction from the works of great shodo artists from across the centuries—or create their own.

The approach I have taken in this book is to expose students to shodo via the artistry and philosophy contained in bokuseki— writings such as documents, statements, essays and treatises that have been handwritten by Zen priests—and, more specifically the one-line statements from Zen philosophy known as zengo. In China, the term bokuseki means any handwritten document as opposed to materials printed with woodblocks, whereas in Japan it refers specifically to the writings of Zen priests. Moreover, in Japan there are nine categories of bokuseki, among them statements written by historically famous Chinese Zen high priests. Examples of these include certificates issued after disciples have completed their studies in Zen practice, or when disciples have received their Buddhist names and titles. Because there is a limited number of historically important bokuseki in Japan, today many living Zen monks, tea ceremony masters and professional calligraphers continue to create unique calligraphic styles and expressions.

One-line zengo encapsulate the essence of statements extracted from bokuseki essays, treatises and other writings. In essence, they are a crystallization or summation of the underlying meaning of Zen writings. They are expressed in a great variety of styles. A single ideogram may be written very large accompanied by smaller ideograms to complete the statement. Occasionally, a sumi ink painting may accompany the zengo. More unusually, a single ideogram or a short statement may be written in a horizontal manner as opposed to the more usual vertical presentation.

The way in which a zengo Zen statement is written vertically and mounted as a hanging scroll, as well as the way in which it is displayed in a Japanese tea room, is called ichigyo mono, a term which emerged in the sixteenth century. Ichigyo mono wall hangings containing zengo are the most revered of all the items on display in the tokonoma or alcove of a tea room. The one-line statement sets the tone for a particular tea ceremony and all accompanying items are selected to harmonize with it. Indeed, both the tea ceremony and Zen share the basic philosophy that all extraneous or redundant activities should be removed and in spirit and action the whole environment should reflect economy and minimalism.

At a cursory glance, the ichigyo mono on display appears to be a simple statement, but upon greater examination and reflection can reveal a profound philosophical truth. Guests who enter a tea room will first approach the tokonoma, study the ichigyo mono on display, then bow out of respect for both the meaning they glean from the statement and the thoughtfulness of the host for making such a fine selection. The bow of respect is symbolically the way to clear the mind of all extraneous thoughts in order to receive the full impact of the statement. Unsurprisingly, the spirituality imbued in the statement has given rise to the dictum “Tea and Zen are the same taste.” But while the Zen philosophical approach is to simplify and remove unnecessary elements, in reality this is easier said than done. It is not simply a matter of indiscriminately removing one element or another; rather, each component must be evaluated carefully before elimination. This same Zen aesthetic concept can be found in the Noh drama, haiku, Zen gardens, black ink paintings and the tea ceremony. All these arts focus on stripping away unnecessary elements, retaining only what is salient and fundamental.

Spiritual enrichment through the practice of shodo is not the prerogative of well-trained Zen monks. Anyone who practices writing a Zen statement over and over again with a brush, learning to control the seemingly unpredictable outcome, eventually should gain greater insight into the meaning of the aphorism. This could be the moment when the enigmatic statement suddenly begins to make sense and through shodo a greater depth in understanding ichigyo mono realized. This is the main purpose of this book—practice as a prerequisite to understanding.

Professional shodo practitioners follow a daily schedule of writing ideograms that employs their artistic visual sense to the highest degree possible. They seek to produce extraordinary beauty in the art of shodo in their careful selection of the type of sumi ink, the kind of handmade paper and the quality of “singularity” of the brush so that the desired effects can be achieved. Their skill in using the brush is, of course, the most significant. If a viewer at first glance feels that there is leftover space, careful examination will show that this is active empty space. The refined beauty on all levels that is the pursuit of the professional shodo artist, when combined with spirituality, will create works that will undoubtedly have an impact on the viewer. On the other hand, students of shodo obviously cannot compete with professional shodo artists in their skill and technique with the brush. Therefore, when an ichigyo mono is carefully scrutinized, the background and character of the creator must be taken into consideration. The respect and honor given to the work is because all aspects of personality and character are im-bedded in the brush strokes. The viewer must retain an open mind and purity of heart and spirit to appreciate the ichigyo mono hanging in the tokonoma.

Generally speaking, people who have had little experience in reading zengo often struggle to comprehend their meaning. Not only do most zengo used in ichigyo mono come from ancient sources, written by famous Chinese or Japanese priests and teachers of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism and others, but the one important line singled out from long sutras and treatises requires some knowledge of the whole. Without prior knowledge of the historical background and context in which the line was taken, interpreting zengo can be a challenge. Indeed, taken out of context, ichigyo mono can be as ambiguous as the contemporary conversation of couples or grandparents. Exchanges such as “I’m for fish” or “ I’m for chicken” can be puzzling unless understood that these are comments made on the way to a restaurant. “My daughter’s is a boy” or “My son’s is a girl” is equally enigmatic unless one understands that this conversation is between two sets of grandparents discussing the gender of their grandchildren.

Since ancient times, literature in Japan has always been regarded as secondary to the practice of Zen. This is reflected in the expression furyu monji (fu=not; ryu=standing; monji=literature), meaning that literature should not stand out and was secondary in Zen practice. Zenki (zen=silent meditation; ki=opportunity) was of paramount importance. In the process of constantly pursuing an answer to a koan—an enigmatic Zen conundrum—the sudden moment of the breaking point or “realization” would come at unexpected times, often during common daily activities or during training. Whether such deep and significant meaning can be found in the practice of shodo is subject to speculation. Certainly, this is not universal for all practitioners of shodo. However, in writing Zen statements and in the attempt to understand their meaning, spiritual energy is expended and vital forces allow an individual to create a work that goes beyond the craft of the brush. The works of these individual artists borders on abstract art.

This book is about how to read and develop some understanding of zengo. Detailed explanations, guidance and notes on how the statements can be perceived are therefore included. Although the bokuseki samples in the book are works by well-known Japanese Zen priests called zenji (zen=silent meditation; ji=master), a title bestowed only by the Imperial court on priests who have been outstanding in dedicating their life to Zen Buddhism, a professional, contemporary shodo artist was specially commissioned to reproduce the bokuseki in the kaisho style to allow ordinary people to read and write the statements in either the formal, square kaisho or the informal, cursive gyosho style.

This book also incorporates, in Chapter 9, the work of neophytes from a variety of backgrounds who take weekly lessons in shodo in my studio. For many of them, practicing shodo is an extension of their practice of zazen. Their work has been deliberately incorporated so that a wide variation in individual styles and nuances can be seen in the writing of the ideograms. Included in the book are instructions for writing these ideograms if the reader so chooses.

If a greater perception or insight into understanding the essence of Zen is gained from either reading about or practicing the shodo in this book, all who have participated in its compilation will be greatly honored.