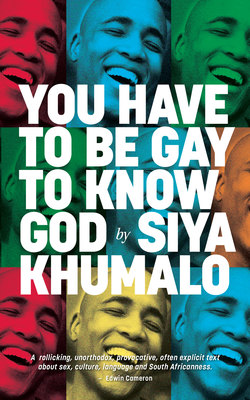

Читать книгу You Have to Be Gay to Know God - Siya Khumalo - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PROLOGUE

ОглавлениеConfession of Faith

At about 5:20 pm on 31 December 2012, a colleague picked up a steak knife from a cutlery tray. He yelled, ‘Angi-gay, mina!’ — I’m not gay! — and came at me with it.

I froze, the takeaway package rustling in my trembling hands. The kitchen staff erupted like a banshee choir into shrieks that he not hurt me. The bar-lady burst through the two-leaf swing doors to see why our chit-chat had turned to yelling. She saw; the colour drained from her face.

A sound I thought was him moving made me jump — it was the chopsticks my elbow had knocked off the counter, bouncing like drumsticks on the floor. I jumped again when I realised that jump could have startled him into stabbing me. My knees wobbled. I had the presence of mind not to reach for the counter for support. ‘I’m not gay! Don’t you ever think I’m gay. Do you hear me?’ he was yelling.

My eyes searched the room’s woks, its fridges and its crackling bug-zappers for something I could grab. Nothing. ‘Yes,’ I said, swallowing the hot gravel in my throat. ‘You’re not gay.’

He calmed down enough for the others to take the knife from him and pull him away.

We were waiters at a restaurant north of the Durban CBD. No customers had arrived because it was early in the shift. The takeaway order had come through over the mushroom-coloured telephone at the end of the bar. When the meal’s owner picked it up in person, nobody gave away that something had happened while we were wrapping it up. He was cheerfully wished a ‘Happy New Year!’ and sent off into the rainy night.

The colleague had arrived late and inebriated (a dismissible offence) as I finished wiping chairs in the dining section. But he’d worked well drunk before. ‘It’s too late to call one of the others to fill in,’ the manager had sighed wearily. ‘I’ll take this up with him after the shift. I must put an end to it.’

Seconds before, we’d been yakking in the kitchen. When I try to recall what we were joking around about, my mind goes numb. I do know those jokes weren’t malicious, about him or even gay-themed. Then wham! At knifepoint, I was reciting a creedal confession of his heterosexuality.

Afterwards, the manager spoke with me as I swept some dust up onto the scoop. ‘We can report this to the police,’ he said. ‘We can have him sent home. Whatever you feel is necessary. It’s your call.’

I thought of suggesting he tell the police captain who lunched at our restaurant about the incident. Beyond that, I didn’t want to open it up to strangers. I could imagine my colleague out on bail, drunk and angry again. I could hear some disdainful police officer dog-whistle say to him, You idiot, when you threaten to stab a moffie you do them a favour bigger than offering them your cock to suck on — you give them something to run here and whine about. Don’t threaten; just do. You pay the right money, case dockets get lost. But people you threaten? Not so much.

I couldn’t tell which decision would be better. ‘I’m okay with whatever,’ I replied, feeling like a lost child who’d peed himself and didn’t want strangers to know.

He peered into my eyes. ‘Are you sure?’

‘Yeah,’ I lied, smiling light-heartedly, turning to pour the sweepings into the bin next to the bar. I think I even threw in a joke for effect: ‘We needed some New Year’s excitement around here.’

He left me to my work and silently gestured to the bar-lady to mix him a strong drink. ‘Everyone knows that you’re just you,’ he added. ‘You have your sense of humour but you never mean anything by it.’

Those well-intentioned words sent me going over every interaction I’d had with the colleague up until that night, starting from when I was a newbie and he was giving me shit. I physically lifted him up and put him some distance away from where I was so I could finish my work. Our colleagues had laughed themselves into a stupor.

Though my rational mind said it wasn’t my problem, another part of me needed to know whether I’d done something to provoke him. I believed in the unspoken promise that if I ‘behaved’ and passed for straight, the world owed it to me not to treat me the way it ordinarily treated ‘other gay guys’. That incident left me feeling betrayed and feeling guilty for feeling betrayed.

I had my first crush on a boy was when I was twelve. His face was a geometric flower of sharp jawlines and smouldering eyes that twinkled when he smiled. He was classically handsome, a young Indian version of the Welsh actor, Luke Evans. When I saw him, I froze like a deer before the headlights of his outrageous beauty. I needed for him to know he had lit up that part of me. But how could I tell him without freaking him out? I was in a limbo of perpetual yearning.

One high holy lunch break, I was looking at pigeons on one of the school buildings when I felt a pair of hands, his, grab and lift me up. ‘I wanted to feel whether you’re as light as you look,’ he explained, laughing. ‘You have lost weight!’ My head certainly felt lighter.

Other kids grew up and dated. I retreated into books and TV, choosing those over the Matric Dance. I’d spent five years looking at unreachable boys in different iterations of their school uniforms. I hate window shopping, so I wasn’t about to subject myself to seeing them in fancier outfits if looking was all I’d get from it.

I already knew which guys’ chest hair showed, almost glistening with perspiration, under their collars when they wore their shirts with the top buttons undone in summer. I knew who cut the hottest, sharpest figures in winter blazers and who the hot nerds were before nerds were hot. One guy in biology class wore metal-rimmed glasses and the girls ridiculed him because he collected snakes. I’ll spare you snake-themed puns and leave it at this: he was a smart, decent gentleman. Was it him I was thinking of when, asked to read from the textbook, I mispronounced ‘organism’ as ‘orgasm’? The class burst into laughter. The biology teacher had the decency to reply, ‘It’s understandable. You must have at least one orgasm in your lifetime otherwise you should spend the rest of your life meditating in The Himalayas.’

However telling my Freudian slips were, I had the presence of mind to stay far away from the rugby players and the obscenely short shorts on their maddeningly muscled legs. But every attempt at clamping down on those thoughts stirred phantom sensations — spinning zodiacs of breath-snatching visions; legs clamped on and around my throat while their angelic faces grinned down at me with delicious cruelty; constellations of bent joints, impossibly strained positions and embarrassingly needed no-holds-barred intimacy.

The most troublesome rugby players were those who doubled as hot nerds. They not only picked up that I liked them, but far from following respectable custom and humiliating me about it they drew me in to sophisticated mind-games with piercing gazes and whispered innuendo — just for shits and giggles.

As puberty developed the guys further, they adopted girlfriends who grazed very fussily at those luscious pastures. For reasons then beyond my comprehension, some of the girls felt comfortable confiding in me about their relationships with those guys. I suspected they knew about me and were playing the same game as the hot nerd rugby players.

‘After I told him how upset I was and that I never wanted to see him again, he took me in his arms and kissed me. What the hell is up with that, Siya? After he stood me up for our first date, and kept me waiting on our second, he thinks he can make it up with a kiss?’

‘How dare he!’ I’d snap. Then I’d thirstily ask, ‘What was it like?’

‘He held me in his tender arms …’

I’d think, I’ve seen the guy you’re talking about. How can his arms be tender when they look so hard and yummy, with those veins clinging so lightly to those beastly bulging biceps …?

‘His lips on mine were so firm …’

I’d be thinking, But they look so soft!

‘You know the kind of kiss I’m talking about, Siya? Have you ever kissed like that?’

I’d pull my drooling jaw back up to the rest of my face and reply, ‘Of course!’ while berating myself in my head: Siya, look at your life! Why can’t you be stood up and have it made up with a kiss like that?

‘Oh yeah?’ The girlfriend of whichever guy I liked would flash me a killer smile before asking, ‘Who’s this lucky lady you’ve been kissing like that?’

‘… Someone I would never stand up!’ I’d reply, my voice ringing with truth.

‘Exactly, Siya. You’re such a sweet guy. Unlike these jerks. For a moment, I suspected you were … never mind. I’ve got a friend who’s looking for a man. Are you sure you aren’t single?’

‘No, it’s okay, I promise I’m not looking for a girlfriend. Focusing on the books, hey.’ More accurately, I was focusing over the books at some of the boys in class, and on the books when I scribbled journal entries complaining that Satan took too long to come at me with all the worldly temptations and fleshly pleasures I’d been warned to guard myself against. But I could imagine the devil’s reason: the longer he made me wait, the more gusto I’d sin with when I was unleashed. That, or I wanted those pleasures so badly, I was already a confirmed sinner and there was no need for him to waste any of his resources on proving it.

Up until the night at the restaurant, I was a ‘good’ gay, complimented often for not being as ‘bad as the other gays’ who were ‘over the top’ about their sexual orientation. I’d been complimented also for not being ‘that bad’ a black person. I never whined about apartheid and I ‘spoke so well’. Another co-worker paid me both ‘compliments’ at once when he explained that I wasn’t really gay; the problem was I’d mostly known black women. But seeing I wasn’t ‘that bad’ a gay or ‘that bad’ a black, all I needed to find my heterosexual spark was one night with a white girl because ‘white girls have class’. The issue was one of taste.

He and I once saw a mixed-race couple cross the street. The man was Indian; the woman, white. He remarked that no white man would ever date that woman again because she’d been ‘chowed by that Indian oke’.

I don’t share these stories about my colleagues for judgment’s sake. When we weren’t whipping out knives or racial slurs at one another, we were developing a shared sense of unconditional acceptance. It was what it was.