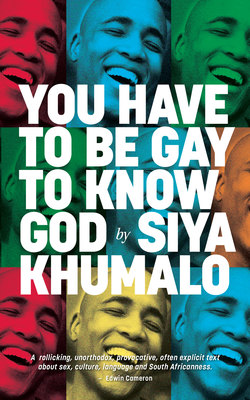

Читать книгу You Have to Be Gay to Know God - Siya Khumalo - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Awakening

ОглавлениеThere was a boy, also seven, who lived in the house across the street from where we were staying. Picture Taye Diggs at that age. He had a new bike. I walked across his yard one afternoon and saw him on it.

I didn’t give this a second thought until I dreamt about him a few nights later in high definition, slow-motion, full colour detail. My mind replayed the moment he glanced up at me, his eyes arresting mine. Sparrow chirps echoed in my ears — high-pitched, fitful. Demanding. They matched my heart hammering in my chest like it was being chased by his flexing legs. And the slower those legs pumped, the harder my heart beat — like there was somewhere I wanted him to get to but he was taking so damn long. My eyes stopped moving at the shaded place along his inner thighs where his skin was its darkest; a different darkness gradated into the shadow where his pants hung loose over his upper legs before tightening over his crotch. There, the fabric bulge folded under him onto the saddle. It strained, like my breath trapped in my chest; like the tubular growth in my groin as it pressed into the bed mattress that pushed back. I dimly sensed I was dreaming, my body sleeping front-down.

The sight of bike-boy’s legs pumping in slow circles matched itself with an instinctive, rhythmic pressing from inside me; I felt my hips, groin and torso grinding into mattress. The pressing feeling was concentrated, almost painfully, to a raging, bone-like hardness that searched for more pushback, more aggression, from the tickly demon fingers squeezing their way up me. Their pressing pulled me, insides-first, down that shaft as it throbbed between my legs, extending, engorging away from me, aching for someone to press against.

Was he cycling, or was he rocking and grinding himself on that saddle? My limbs restless, I realised I wanted to be the bike so those terrifyingly smooth limbs could clamp down on me with their boyish voluptuousness. I’d want him, not to pedal as loosely as he was doing, but to really squeeze himself against that bike; to use it. To crush it; to wear it out. The languid way he was cycling was torture; I felt like he was teasing me.

With all my will I squeezed the duvets between my knees; I rocked and bucked myself into the bed, running my groin up and down over it, feeling through the sheets the ribbing, the give and the springs of the mattress many of us cousins shared. Breathy and breathless, I was climbing towards something — and I woke up before I could quite figure what, exactly.

Too awake to black out and too tired from wrestling myself to get up, I realised I had a secret to keep buried and indoors. I was different. The other boys had sensed it, too. My mother had promised to get me a BMX with 20-inch wheels but she never had to: I never asked for one again, and I stopped spending enough time outdoors with other boys to need it.

It was 1994. The country, too, was undergoing an awakening. Black people were set to participate in the first democratic elections. In view of the conflict in KZN, everyone in our house was warned never to go outdoors with any political material — not a nipped election ballot sheet, nor a party flag, nothing. We kids were warned those things were not toys. And no matter if our peers were repeating things their parents had said, we were allowed nowhere near discussions on political leaders like Nelson Mandela or Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

Between 1990 and 1994, I also discovered there were neighbours who kept fireworks for special occasions. Like they had when Nelson Mandela was released, they launched those when the ANC won the general elections. Our newly-minted freedom was pretty pops of colour against the night sky. Not having fireworks, Mom burnt steel wool and waved it about, throwing sparks to the cool, darkened ground. The scourer looked like loopy joy scratching glow marks that quickly faded off the skin of the night.

She was dancing in the black-and-white polka dot maternity gown she wore when she was pregnant with my younger brother. My sister and I initially peeped out at her from behind the closed lower half of the stable door to the kitchen. I’m sure we hoisted our brother up to see; Mom swung past and picked him up, planting him on the ground. His subsequent fat-calved imitation of her dancing suggested he knew less than we did about the occasion. On Mom’s invitation to join her witch’s dance, we unbolted the door, swung it open and plunged ourselves into the cool night livened by her sisters’ ululation.

We’d danced to the front yard, my mother and aunts chanting, ‘We’re free!’ when a new kind of firework exploded — bone-rattling, rapid gunfire.

‘Mariya Ocwebileyo!’ Holy Mary! Mom’s shoulders jumped in shock, confused frown lines crossing the parts of her back I could see through the dress’s rip on the right shoulder. Steel wool tossed aside, she swept the youngest up while driving us towards the front door. Neighbours’ voices screamed in panic; adult feet thudded and little feet pitter-pattered into the house.

The door was bolted behind us as the grown-ups waited with bated breath for the head count to account for all the brats and adults — amen! And we, too, were under the furniture but because we were small we didn’t have to stick our bums in the air. We could disappear completely under the dining room table where we’d always played hide-and-seek indoors. It had always been safer to play indoors.

One day in 1994 the rain tried to wash our seven-year-old bodies off of the township streets. By the time I arrived at school, classrooms were half-flooded and half-littered with rain jackets and kiddie umbrellas. The teachers were talking among themselves. We all hoped they’d let us go home early, but we wouldn’t put much stock in it in case we were disappointed.

‘Bazosigodukisa,’ some kids were saying. ‘Ngeke, abasoze,’ others replied. They’ll let us go home; No, they won’t.

One of the teachers stepped forward to talk to us. They were announcing their decision sooner than I’d expected. ‘Children,’ she called. ‘Due to the weather, we’ve decided that we’re cancelling the whole day. You can all go home right now.’

The Rapture couldn’t have gotten us out of there faster. All I wanted to was watch cartoons on TV and eat food.

The wind picked up as we braved the hills to our different streets. But the gusts became strong enough to lift me off the ground, bits of people’s yards hitting my face so fast I could barely see the way forward. I was on the open road without a lamppost to hold on to.

Luckily, there was a church along the way. I pushed against the wind and the rain to get to it, running for the door because the clean, stark-white edifice had nothing to hold on to. And as I tried to push it open, I discovered something my seven-year-old mind couldn’t compute: it was locked. I’m not trying to be cheesy but I asked myself, ‘If church doors can be locked, then where do people run to from the storm?’ because that, in a nutshell, was the start of my journey with religion.

The wind was so bad I wouldn’t move away from the doorway. Which was also how I would deal with the prospect of losing religion. I decided better the devil I knew than the one I didn’t even as I silently prayed for divine assistance. Not two seconds passed before a boy I didn’t trust very much came running by, promising to get me through the winds and floods in one piece if I went with him. Much to my surprise, I got home with his hand holding mine as he’d promised (he also made it home safely)! And that, symbolically, is my current journey with faith and spirituality as opposed to religion.

When I got to my grandmother’s house, I was duly fussed over and fed. Dry, warm and full-stomached, I lay under some blankets, drifting off to sleep with my extended family members chatting and eating soup with bread around me. I woke up later and noted the sun was out and the world scrubbed so sparkly it could have starred in its own toothpaste commercial.

One of my cousins had also gotten home from high school. He was telling a story about how he’d put a guy in his place. He described the guy as is’tabane.1 The scene he was describing flashed before me; I envisioned it happening in a dip on the road where kids walking from high school passed people coming from town in the afternoons. I cringed in embarrassment at the intimations that this gentleman failed to act like a ‘real man’. I shuddered with disappointment as I sensed that my extended family members’ compassion for all living creatures was tempered by this idea that this guy could and should have made life easier for himself by not being in danger’s path; by not acting so … gay.

The boy on the bike rolled, uninvited, into the darkness under the blanket over me. The vision was not just the product of the sleepy dimness I was wrapped in, nor of the pinpricks of rain-flossed sunlight threading through the fabric. He was projected by a piercing desire in my soul; a dreaded yearning that threatened to push up from inside to erupt over my body. This time, I was lying facing up on the same bed I’d first dreamt of him, feeling a bittersweet need to mean as much to him as he did to me. With voices talking around us, he climbed on me, his bike tossed aside. His ghost hands pinned my joints down; his weight crushed me in a way that was relieving and deepened the need for release. That climbing feeling crept up through me again; I fought my body’s urge to stretch up; I pulled the overwhelming longing to erupt back in; I resisted the urge to draw a breath.

I didn’t know whether to stay hidden with the vision of him or throw the blanket off and expose us to the soup-eaters and gay-bashers. He would probably disappear because not being flesh and blood and passions, he was more sensible than I; I was in this all alone. He’d never acknowledge what he’d called forth in me and until then, there wasn’t enough room in the world to hide us.

All that, from a story about is’tabane. Why was I feeling all these things?

If I tried to turn over, I would overturn him while calling attention to myself. So I lay still, not knowing whether the boy on the bike was really there or just my fantasy. Either way, anyone who looked in my direction would see the unaccounted-for lump of him on me sticking up from under the blanket.