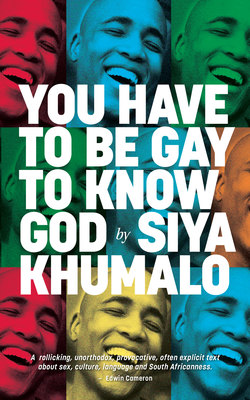

Читать книгу You Have to Be Gay to Know God - Siya Khumalo - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 2

ОглавлениеGrowing Up in a Funeral Home

We had so many funerals at my maternal grandmother’s house, we could have recovered the money we spent on them by sourcing supplies and services for other families’ funerals. It was unusual that I lived there in the first place. Maybe some background on how that came about would help.

In Zulu custom, it’s normal for a young couple to live with and be ‘incubated’ by the husband’s family. My parents tried that. Between them, Mom and Dad now have three daughters and two sons on earth. While we were at Dad’s parents’ home, my paternal step-grandmother accused my mother of witchcraft. Mom shot back something along the lines of, ‘That’d be the pot calling the kettle black’, which suspiciously, wasn’t a real denial …

Anyway, our family had to up and leave. Dad’s mom had passed away giving birth to her nth child — a number guesstimated to be in the teens — and his remaining siblings died one by one, leaving one sister. My paternal grandfather remarried often. One of these wives controlled the money bag when Grandpa was away working. With that, she controlled his children’s access to food, medication, schooling and everything else they needed, prioritising her children over Grandpa’s. My dad and his siblings told their dad about it, but times were tough and he appeared to choose her over them.

In a suspicious show of concern just after they started planning to get married, paternal stepmother V4.0 nit-picked all the ways Mom was bad for Dad. Traditionally, a marriage is incomplete until there’s a first child. A son, if the couple can see to it. As if in rebellion against the stepmother’s resistance, my mother and father saw to it. Quite unaware of the controversy I was stepping into and all the expectations that come with being a son, I made a deal with the devil and agreed to be born.

My first name, Siyathokoza, means ‘we are happy’. My second name is Thabani. That means, ‘be happy’. I was my mother’s victory cackle made flesh, padding about on two infant feet. Incidentally, Thabani is also the name of a gentleman who scooped my toddler body out of the way of a speeding construction truck. Doesn’t the Lord have a funny way of making his providence known?

‘Doesn’t he just?’ I replied to Mom as she told me these stories, saying nothing about her emphasis on her own fabulousness. I was a teenager of an age I won’t disclose, and she was trying to get me drunk because I was highly-strung and could go a worrying number of years without doing anything rebellious. What happened instead was she got drunk, spilled the beans, and I was too busy hanging on to every word to touch my drink.

I also had an older brother through Mom’s prior engagement with a now late gentleman. That baby passed away before she and Dad were a couple. Mom described the baby as tall. When she speaks about him, she becomes a different person animated by a set of costumes she never got to try on out in the world. When I was born with difficulty swallowing, she panicked and thought I was also plotting an early exit, which I’d have given good thought to had I known better. She was especially freaked out when I, infant of days, yanked the feeding tube out of my nose. I distinctly remember doing this. The nurses at the hospital thought she’d done it and had undiagnosed psychiatric issues that caused her to blame the baby for her actions. So, I’ve been landing Mom in trouble since I was born.

As unconscious as they were, I’d sensed my spiritual and sexual awareness was intertwined by the time I was a pre-teen. At eight, my GP recommended that I get circumcised. My parents and I were as excited about it as anyone can be about the Abrahamic cut, but the procedure was postponed for months because I had a dream. When I woke up and told them about it, I didn’t anticipate the disruption it would cause.

My dream day began like any other school day. I was helping pack my lunch into a hard-cardboard briefcase with metal fasteners when I realised I hadn’t seen it in years. Jesus Christ, why was my old baggage popping out of nowhere?

Anyway, I had to go to school. It was a sunny day, and I walked past dream-trees waving in the wind, haloed in liquid sunlight. They looked like slow-motion fireworks’ displays of chlorophylled life dancing in the sun. Along the way, I met an old lady. She dropped her walking stick and asked me to pick it up for her. As I began reaching for it, it stretched out of my reach. It also expanded to dominate my field of vision, becoming the tilted focal point of a dolly-zoom effect. It looked dark, viscid, alive — an electric nimbus around it warning me to come no closer.

Naturally, everything in my being was drawn towards it. I was shifting, its gravity calling to the cells within my cells — a part of me that had been clothed and hidden as far out of sight as possible. But now it was emerging, right there, in the open.

The old lady looked expectantly at me. Conflicted, I pushed my hand through the field surrounding the stick. It pulled me in and annihilated me with a powerful charge. No, I realised, I hadn’t been annihilated. I’d been split in two, one part of me dead on the ground, school things and lunchbox tumbled out of the school bag; the other part of me had been wrenched up into the air where it was flailing.

I was barely through the whole story, and in far less detail than I’ve shared here when my parents figured they didn’t need to hear more. As soon as the sun was up, they phoned the GP to postpone the circumcision.

‘These two sides of yourself …’ Dr Govender would say years later, his hands up in the air like mine. I would see him shift them closer together, slowly — and I’d panic. He couldn’t do that! They couldn’t be allowed to meet. That would be a disaster. Didn’t he understand?

But his face was peaceful; his voice was reassuring. So, I let him finish his question. ‘Is there any way these two sides could ever … merge?’ He let the suggestion hang. ‘Can you imagine them ever being at peace with each other? Wouldn’t that alleviate a lot of tension?’

‘No,’ I replied, and he seemed to respect that.

But something about how he’d asked the question told me I didn’t have to know how it would happen. I just had to let it happen when it was ready to. His words had softened some ground. Although dear God, what was trying to sprout from there?

My paternal step-grandmother was our family’s fall-back suspect for all domestic witchcraft. Her broomstick’s runway was probably the arid dirt strip in her backyard where tough, hawk-like neighbourhood chickens — proper local and free range — scavenged leathery worms. One of my nephews said the lady kept thirteen roses on her mantelpiece. That was one for each of us in the extended family born to her late husband. Each time someone died, one of those roses would fall over.

‘I don’t think grandmothers normally do that,’ I replied, bug-eyed.

In black township and farm lore, a witch’s job is to keep things interesting. If you don’t secure your bloodline through at least one son, you’ve handed your legacy over to them for annihilation. I was Dad’s first son and how his bloodline was to triumph over the reign of his evil stepmother. According to my grandfather I was to meet a nice girl, get married and raise 2.4 kids in a house with a white picket fence. But I had to be careful about the family she came from. There were ancestral feuds to remember; there was inbreeding to avoid and undercover sorceresses to watch out for.

‘Yes, Grandpa; I’ll make sure to remember that,’ I’d reply, my eyes meeting with his greying ones. Both pairs silently said we were bullshitting each other, but we had to perform this ritual to give his hopes an outlet. After he passed, a neighbour told me he’d requested that on my wedding day (to a woman), ‘amusinele’ — that she perform the traditional Zulu dance on his behalf. He didn’t see me getting married in his lifetime. I also found out he asked for change when he gave offering money in church (good!).

A few years ago, my mother fired a helper who saw it fit to say, ‘Akukho makoti ozoza la’; you’re not going to get a daughter-in-law from this son. I had mixed feelings as I was told this story. My mother couldn’t see how it cut me to the quick to find out. Maybe she saw but thought I needed to know. Who knows what else she’s shielded me from?

Back then, if I had a health issue — if I knew in my gut I was fundamentally different — and the doctors said it was the psychosomatic symptom of an unexplored anxiety, my shrewd elders would nod submissively before saying amongst themselves, in Zulu, ‘Westerners don’t know what they’re talking about. It’s ancestors. If not them, it’s sorcerers. Those bastards are trying to kill the children so their houses are never established.’

But I think we all knew on some level that born as my parents’ answer to a witch, I was a form of witchcraft all of my own.

After my mother and her stepmother-in-law had their spat, we left for my maternal grandparents’ house on the small block off of Main Road in another section. This house was ‘the funeral home’.

While there, I managed to get my chubby little one-year-old hands on a home-made ice lolly we called is’qeda. Before anyone knew what had happened, the ice blew a minor cold into bronchitis or pneumonia. It seemed the sorceress’s muti had followed me across the township, landing me in hospital with more pipes going in and out of my body than my family thought was possible. To Mom, this was frighteningly like the time my older brother died. The prognosis was hopeless. Then she heard the step-grandmother intended to visit me in hospital — ‘She wants to do what?’ She wasn’t allowed to come roaring up on her broomstick.

I survived the medical odds stacked against me, inadvertently proving I was the son who would triumph over whatever battles our family was involved in. That wife and 2.4 kids were determined to happen. My more immediate concern, as I vaguely recall, was relearning eating and walking. I was skin and bones. My panicked mother took me to the doctor. He insisted I was healthy. ‘What’s healthy about this?’ she protested. He gave me something to help me gain weight and it worked! She took me back to complain, ‘He’s swollen!’

The doctor said I’d been fine before and I was fine then; that’s just what the food supplement did. Add that to everyone’s fear of letting me do anything in case I got sick again, you’ll see why I became a fat, sheltered kid whose weight yo-yoed up and down. My face probably screamed, ‘Bully me!’

I had been born in 1987, my younger sister followed practically holding my heel in 1988, and my younger brother holding hers in 1989. His name translates to something like, ‘That’s all folks!’

When I was about four or five my parents moved us to a house in another corner of the township. We’d been there for months or years when one afternoon, I got a strong urge to go to my grandmother’s house. I pestered up a storm. A family friend agreed to take me. I was quiet the whole way. When we arrived, it was crowded and rowdy. My maternal grandparents ran an in-house shebeen to make extra money. One of their sons was a cop who did things by the book but they’d somehow made it work since apartheid days. There was a soccer match on TV, which took my discomfort with the scene above my normal tolerance. I hated sports, an oddity my maternal grandmother found infuriating. ‘What use is a grandson,’ she’d joke affectionately, ‘that I can’t watch sports with?’

I wanted to go back to my parent’s house. I must have been crazy, asking to come here! Not caring about losing credibility, I prepared to pester someone to take me back when a stern voice in my head said, ‘Sit!’ Startled, I planted myself on the chair next to the front door and stared at the ceiling fan to pass the time.

The next morning, we woke up to hear my parents’ house had been robbed and my family held hostage at gun and knifepoint. One of the burglars had slapped my four-year-old sister out cold. No one in my family felt safe in that part of the township after that. Dad had previously been mugged on his way home from work. The expression for this baffled me. ‘Ngibanjwe inkunzi,’ he reported, with pent-up tears in his bloodshot eyes. My siblings and I repeated these words amongst ourselves, baffled and shaken. Ngibanjwe inkunzi literally means, ‘My bull was grabbed’; you say it when you’ve been mugged.

Years down the line, our family life was racked with more traumatic incidents. My parents’ house was burgled twice while Dad was away working the night shift. He once drunkenly asked me why I hadn’t defended the house like a man. I must have been ten? Eleven? I eventually realised that beneath that outburst was his fear that I wouldn’t survive as who I was, and it would be on him as a father. Love has funny disguises like that.

The question that repeatedly came up was, were all these troubles coming from the witch Satan had assigned to our family? Just as every black township family has a ‘family farm’ in its background, each of those has a resident witch. And witches don’t sleep.

After the hostage situation, my parents moved us back to my maternal grandparents’ house where they’d gone after being chased out of my paternal grandparents’ house. I changed schools from the one my father went to when he was a kid to the one my mother went to when she was a kid. At seven, my life was reaching its first full circle. It was then, before the dream about the walking stick, that I first had a dream confrontation with my sexual interest in boys.