Читать книгу Many Blessings - Sonnee Weedn PhD - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

I am the great, great granddaughter of a man who fought for the North in the Civil War. “He was with the Wisconsin Regiment,” Grandmother Delight would tell me with great pride. She added a little more to the story by saying that he and his compatriots were without food for many days. They stopped at a farmhouse and asked to be fed. The farmer not only fed them, but also said that they could sleep in the barn, where his wife brought them a provision of grain to take with them. She had packed the grain in several of her long, black woolen stockings; the only containers she was willing to part with.

As a child, growing up in a white, middle-class family, I had only a few encounters with African Americans. As Minnesotans, we were the white subjects of de facto segregation, though my parents wouldn’t have understood this or thought about it at all. Blacks, or “colored people,” as they were called then, were simply unknown to us. In 1950, when I was four, my father was called up for the Korean War. He was a fighter pilot, and we were sent to the Marine Corps base at Cherry Point, North Carolina, our first experience with the segregated South.

My mother was told by the neighbors that she should hire a “colored girl” to help keep house. And so entered a sweet, silent woman, named Willie Whitehead. I was only four, but I can see her face today: shiny dark skin, and a halo of fluffy hair. She was young, I think. My mother, who was only twenty-six, was told that she must keep a separate set of dishes and silverware for Willie. She didn’t really understand the reasoning, but did as she was told, marking each plate and utensil that Willie would use with red fingernail polish on the bottom.

Within weeks my mother decided that the whole idea of these separate dishes was ridiculous. “Willie Whitehead is cleaner than we are,” she said. And that was the end of that.

We only stayed in North Carolina for nine months before heading to California, as my father was sent to Korea. But, the red marks on the dishes served as a reminder of Willie Whitehead for all the decades of their use.

In 1956, my family transferred to Cape Canaveral, Florida, where my father was a test pilot. Once again, we were experiencing the segregated South. My parents abhorred it.

Our housekeeper was Doris Rivers, and she was married to James Rivers. Doris was a registered nurse. Her family had sent her north to school somewhere. But, there were no jobs for “colored” nurses in our small town. Nevertheless, various members of her family took turns heading north to school, despite the lack of real opportunity.

Doris would sometimes babysit us children when my parents went out in the evening. My mother would insist that her husband join her at our home for dinner because she didn’t think a married man should have to eat his dinner alone. The next-door neighbors called the police and the police came to remind Mr. Rivers that “colored” men were not allowed in our neighborhood after 5 p.m. My parents arrived home soon thereafter, and my mother ran the police off, saying that no one was going to tell her who was going to be a guest in her home. She never spoke to those neighbors again, and even though they were teachers at our elementary school, we children were advised to have nothing to do with such ignorant people.

When I was ten, I was a Girl Scout. We were still in Florida and my mother realized that there were no Girl Scouts at the colored school. She called the national office of The Girl Scouts of America and told them that it was a disgrace that most employed people in our area had money automatically deducted from their paychecks as a donation to The United Way, which supported the Girl Scouts. But, only the white people benefited from this charity. She was informed that if she was willing to start a Girl Scout troop at “that” school, she was welcome to do so. They would fund materials and uniforms.

And so my mother recruited me, and we started the Girl Scout troop with the help of Mrs. Lewis, the teacher at the colored school. It was simply our task to help them get started. We did that by going to the school once a week for a period of time and teaching Girl Scout songs and providing curriculum. They got their uniforms, pins, and handbooks, and they were thrilled. I was only ten, but I remember being struck by the fact that the children were cleaning their own classroom (no custodian), and learning to read from old Life magazines (no textbooks). But, when it came time for the all Girl Scout “Sing” at the local Civic Center, these new Girl Scouts could not come, because the white leaders of the city would not permit it. “We don’t have any bathrooms for colored people,” they said. “What if one of the little girls has to go to the bathroom?” And so it went.

We left Florida in 1959. My mother begged Doris to come with us to California. But she declined, and after some years we lost touch with her. Through the years, I have thought of these lovely women, Willie Whitehead and Doris Rivers, many times. What became of them? I have searched for Doris with no success.

My life has been lived, since then, mostly in the actuality of de facto segregation. This has not been intentional, really. It just tends to be a common reality of American demographics.

And so, it was quite a surprise and a blessing when a young, urban, African American woman entered my life requesting to be a patient in my psychology practice. She was young, courageous, and brilliant. She could be profane, too, and she made me laugh.

She had called my psychology office requesting to enter psychotherapy. I was well aware that I knew nothing of African American culture. I felt inadequate to treat her and told her so. But, when I expressed my concerns to her, she was adamant in her desire to continue with me and in a therapy group made up of white, upper-middle class women. To say that we all learned a lot is an understatement!

I looked around to see what education I could find for myself on treating diverse populations. At that time, there was little available, but I found a class called “Race Matters” and quickly signed on for a weekend intensive experience. I was the only heterosexual, White Anglo Saxon Protestant in a class of twenty-five or so students. Where were the rest of us, the dominant culture?

What I learned was invaluable! I only wish that every member of the dominant culture, i.e. caucasian heterosexuals, could take a similar class. We discussed the implications of privilege in ways I had never previously considered or realized. I had never thought of myself as terribly privileged. I had started working as a young teenager. And I had worked all through college, unlike many of the young women I considered truly privileged who didn’t have to work. My ignorance really showed!

I learned to be the first to extend myself in any encounter with a minority person, even if I risked rebuff. It was up to me to take that risk, because of my privileged status, and it was actually much less physically and emotionally risky for a person from the dominant culture to do this than for a member of a minority group. I learned to try to be sensitive to cultural issues, though I often failed. But, learning to fail gracefully was part of the learning. When I made a mistake, I had to learn to apologize for my ignorance or insensitivity and try harder. There was so much to learn!

I had a Ph.D. and thought of myself as an intelligent person with liberal leanings. I experienced my own ignorance and felt humiliated. At the same time, I was delighted by the opportunity to learn and practice a new way; a way that would bring the richness of increased diversity to my everyday life.

When the class was over, I didn’t necessarily know much more about African American culture; but, I had learned more about my own assumptions about life, in general, and how they didn’t necessarily apply to everyone, as I had foolishly assumed.

So, back to my patient… She welcomed me into her world, and though there were certainly rocky moments, our affection for one another has continued over the ensuing years. Though she moved to the opposite coast some years ago, we have remained in close contact.

Because of my experience with my African American patient, and my “Race Matters” class, and because of my interest in women’s issues, in general, I began to think about how it might be that African American women, usually perceived to be from the bottom rung of the social and economic hierarchy of the United States could rise up to succeed and claim their destiny in such diverse ways. These women often seemed to be invisible, no matter their achievements or the actual circumstances of their backgrounds. I imagined that they must have valuable wisdom to impart and that someone just needed to ask them about themselves. I also thought that the Civil Rights movement and the Women’s Rights movement had come about in close proximity time-wise. And, that as a result, the opportunities for African American women’s achievements to be recognized were probably more possible now than ever before as the cross-currents of these two social movements converged.

In addition, I believed that African American women born during segregation, and still alive today, would represent a particular segment of U.S. history that would not be repeated. Their stories needed to be told!

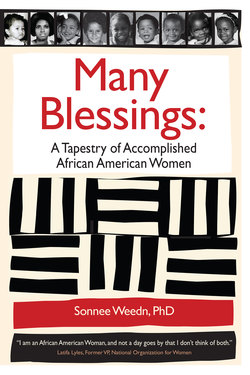

So, I set about to interview accomplished (in the broadest sense of the word) African American women. I asked them to tell me their life stories and how they achieved what they had achieved. Thirty of them did just that, offering their stories along with their wisdom and advice to others.

How did I find them? How did I choose them? Well, I started by asking my patient. And, then I began cutting out magazine and newspaper articles about African American women and I developed a very thick file of them. I approached women who just looked interesting (“Oh, hello. I’m writing a book. May I interview you?”) And, friends and colleagues gave me names and telephone numbers of women they knew and recommended.

I sent letters of introduction and followed up on those who responded, flying all over the United States to interview these generous women. More times than not, I would have to stop the interview midway, as my interviewee and I took time to compose ourselves, before continuing, because the conversations were emotional.

Each interview was wonderful in it’s depth and complexity, and I would call my husband after each one to say, “Now, this one was really amazing!”

I have abiding respect for these amazing women, who are clearly just the tip of the proverbial iceberg. They have seen to it that people around them are made better just because of knowing them. I am better for having known them!

And, so, this book is the story, not only of thirty accomplished African American women, but also of my own journey in meeting and interacting with them. It has been a delightful and enriching experience, which also had its frustrations and challenging moments. But, then overcoming obstacles is part of every woman’s story.

My teacher, Albert Sombrero, a Navajo man and Spirit Guide, says that it is time to repair the Sacred Hoop. By this, he means that at this time in history, all races and creeds are meant to come together in peace and understanding for the healing of our world and it’s people. He says that his grandfather told him that this turn of events signals the beginning of “The Glittering Time.” This book is meant to be a contribution to that goal as we enter The Glittering Time. May it be so.

—Sonnee Weedn, Ph. D. 2011