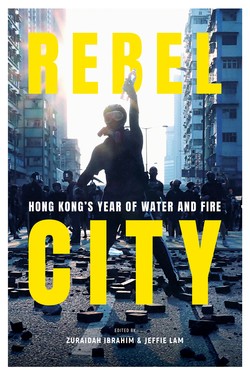

Читать книгу Rebel City - South China Morning Post Team - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A crisis unfolds

ОглавлениеWhen news first spread of the young woman’s gruesome death, nobody could have imagined the case would spark the biggest political crisis to have faced Hong Kong since the city returned to Chinese sovereignty in 1997.

The problem was that while Chan had admitted killing Poon, he could not be tried in Hong Kong for an offense committed in another jurisdiction. Nor could he be sent against his will to Taipei as the two cities lacked an extradition agreement.

Instead, the best Hong Kong could do was charge Chan on theft and money-laundering offenses related to the use of Poon’s credit card, an outcome that would be hard to disguise as anything but a travesty of justice. In Hong Kong, murder carries a mandatory life sentence, while the maximum punishment for money laundering is 14 years in prison and a HK$5 million fine. What’s more, given the relatively small sums involved, it was likely that even if he was found guilty, Chan would receive a substantially lighter sentence and could be freed within just a year.

It was against this backdrop, with Poon’s parents repeatedly appealing for their daughter’s killer to be brought to justice and the Taiwanese authorities eager to pursue him, that Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor proposed changing the law so that Hong Kong could extradite fugitives on a case-by-case basis to those jurisdictions it did not have agreements with.

It had been a year since Poon’s death when Lam introduced her extradition bill in February 2019 and Chan was in remand, still awaiting trial. Lam said the bill had been inspired by Chan’s case and the need to close the loophole that was preventing him facing trial for murder.

Immediately, there were backers for the bill, with the pro-Beijing political party, the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong, holding a press conference on the day of its introduction to give its seal of approval. Poon’s mother was among those who spoke at the event. She said she and her husband could still not accept the fact that her daughter was gone or that, one year on, her killer had not been brought to justice.

“The cruel scenes of how the murderer had carried her body around in a suitcase, dumped it in bushes and allowed the stray dogs to eat it keep creeping into my mind. It breaks my heart,” she said, weeping. “The only thing we can do for our daughter is to make sure justice is served.”

Given the grief-stricken backdrop, Lam might have thought passing such a bill would be relatively straightforward. It needed to be done before Chan was out of prison and could in theory flee the city.

But from the beginning there were persistent criticisms from a public that would not be easily silenced. Opponents said the bill, supposedly created to fix a legal loophole, would create even bigger loopholes of its own. Not only would it pave the way for extraditions to Taiwan, it would also – far more controversially – open the floodgates to extraditions to mainland China, something many people suggested had been Lam’s real motivation all along as an attempt to ingratiate herself with her political masters in Beijing.

Even more damaging was that many critics – some of the top legal minds in the land among them – felt that the bill represented an erosion of the “one country, two systems” arrangement under which Hong Kong was governed and which provided the foundation of its independent judiciary.

Whether the criticism was fair or not, an increasing number of Hongkongers believed the bill threatened their way of life and they were not willing to go down without a fight.

With Lam sticking to her guns, the ranks of the dissenters began to swell, their anger gathering steam and finally erupting into largescale marches and demonstrations from June 2019. Eventually, Lam relented and formally withdrew the bill in September, but by then it was too late.

The protests had already morphed into an increasingly violent anti-government, anti-Beijing movement, with demands for greater democracy and police accountability. Masked radicals blocked roads, started fires and hurled petrol bombs at police. They smashed up MTR stations and any businesses they deemed as linked to Beijing. Thousands were arrested, with hundreds facing the charge of rioting, which carries a jail term of 10 years.