Читать книгу Rebel City - South China Morning Post Team - Страница 24

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

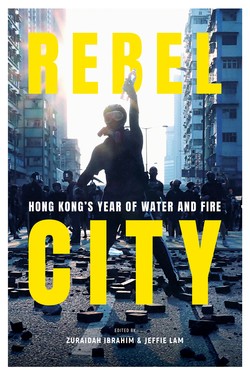

A fugitive, frozen in time

ОглавлениеChan’s pledge to surrender gave a sliver of hope that the family might yet get the closure they had so desperately longed for. At his side that day was Reverend Canon Peter Koon Ho-ming, a senior Anglican priest who had been visiting him in prison every week and had helped persuade Chan to surrender to the Taiwanese authorities. The priest’s presence made Chan’s willingness to repent seem genuine, but in a development that piled only more pain onto Poon’s parents, the worlds of politics and justice were once more about to collide.

At the time of Chan’s release, Taiwan’s presidential election was looming and the incumbent Tsai Ing-wen had made the issue a staple on her campaign trail. Her Democratic Progressive Party, which leans toward favoring independence from mainland China, had played up the Hong Kong protests as an example of how Beijing was encroaching upon and curtailing the city’s freedoms. It was a cautionary tale, she warned, of what might happen were Taiwan to reunify with the mainland.

Meanwhile, Taiwan and Hong Kong officials were also bickering over how to send Chan back to the self-ruled island, and the argument became increasingly bitter. At one point, Tsai’s government had even suggested Chan’s offer to surrender might be an elaborate plot, hatched by Beijing, aimed at circumventing the need for formal negotiations between Hong Kong and Taipei (something that they alleged could be seen as implying recognition of Taiwan’s claims to self-rule).

Given the political sensitivities, Koon said Chan felt he would not get a fair trial in Taiwan until after the election in January 2020. So Chan would hold back on handing himself in, at least for the time being.

Tsai won the election handsomely with 57.1 per cent of the vote, the highest winning margin ever achieved by her party. Most analysts saw her stance on the Hong Kong protests as the main reason.

Yet even with the election over, the time for justice had not arrived. The next month, the outbreak of the coronavirus prompted Taiwan to restrict incoming travel from Hong Kong. The chances of Chan’s surrender seemed suddenly more complicated than ever.

By now two years had passed since Poon’s death, during which time the political landscapes of both Taiwan and Hong Kong had been transformed, yet somehow the prime suspect in her killing still appeared no closer to facing a murder charge.

At the time of publication, Chan remained in Hong Kong as if his case were frozen in time, an inconvenient reminder of a period some would prefer to forget.

As Reverend Koon put it, life for Chan was “at a standstill.” For Poon’s parents, so too was their search for justice.