Читать книгу Rebel City - South China Morning Post Team - Страница 46

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

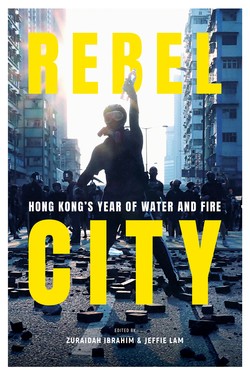

The storming of Legco

ОглавлениеZuraidah Ibrahim and Jeffie Lam

On the anniversary of the handover, an angry crowd attacked the legislature, ransacking the chamber and issuing their demands.

July 1 has been a bittersweet day for Hong Kong for more than two decades. On that day in 1997, Britain returned the city to Chinese sovereignty. Less than 24 hours later, thousands of people braved intermittent rain to march on the city’s streets, demanding democracy. Since then, the anniversary has been marked by both official celebrations and street processions, with the turnout surging or shrinking each year depending on the issues gripping Hongkongers.

In 2019, the handover anniversary arrived amid a build-up of protests against the government’s extradition bill, with two massive street marches in June. As in previous years, there was a July 1 march from Victoria Park in Causeway Bay. It attracted about 550,000 people, by organizers’ estimates, who took part in a largely peaceful march. But most of the action that day occurred at Tamar Park, in Admiralty, where thousands of demonstrators had gathered from the early morning. Mostly young and masked, they barricaded key roads in Admiralty and Wan Chai and clashed with police, pelting officers with corrosive substances, eggs and bottles.

In the evening, at about 9pm, a mob smashed its way into the Legislative Council building. Unchecked by police and ignoring the earlier appeals of lawmakers urging them to stop, dozens made their way into the chamber where Hong Kong’s legislators meet. Over several hours, they vandalized the premises, smashing official portraits, defacing the emblem of the city and spray-painting protest slogans on the walls. It was well past midnight before the last protesters left. July 1, 2019 marked the day the extradition bill protesters entered uncharted territory, ransacking an institution, pledging more confrontation and violence ahead.

City leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor’s day began with a change of plans for the official flag-raising ceremony and singing of the national anthem, March of the Volunteers. The 8am event was moved indoors for the first time since 1997, ostensibly to avoid a drizzle, but the authorities were more worried protesters would interrupt and ruin the festivities. So, instead of gathering at Golden Bauhinia Square in Wan Chai, Hong Kong’s top officials, dignitaries and guests made their way to the nearby Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre for a muted celebration. Lam had announced the suspension of the unpopular extradition bill two weeks earlier, but protesters were not satisfied and insisted on its full withdrawal. In her anniversary speech, Lam promised to reform her style of government and improve communication with lawmakers and people from all walks of life, including young Hongkongers. She acknowledged the need to “grasp public sentiments accurately.”

Over at Tamar Park, a stone’s throw from government headquarters and Lam’s office, the black-clads were already geared up for action. They started arriving from about 4am and, by daybreak, had erected metal and wooden barriers on roads in the area. Overnight, someone had removed the national flag from one of two flagpoles and replaced it with their protest ensign, a white bauhinia flower against a black background. As their numbers swelled through the morning, they blocked Harcourt Road, fronting the park, and nearby streets leading to the Legco building and government complex. By lunchtime, there were thousands in the area, with hundreds gathered around the Legco complex. As tension mounted, frontline protesters charged at police, who responded with pepper spray. Protesters hurled a corrosive liquid – believed to be drain cleaner – at the officers, sending 13 to hospital.

According to protesters present, there was no method to that day’s mayhem. At earlier protests, participants discussed their plans in advance, using the encrypted messaging service Telegram. This time, however, decisions appeared to be taken on the fly and by small groups. At about 11.30am, a protester in a green mask called out to about 30 people at Harcourt Road: “Show your hands if you agree to escalate and go radical.” Most raised their hands. Next, he asked: “Do you prefer to remain peaceful?” No hand went up. Their preference was conveyed at around noon to the larger group of about 200 near the Legco building.

Random protesters then tossed up ideas about what they should do, including suggestions to storm Legco as well as government headquarters. Most supported breaking into Legco, but there was no concrete plan on how exactly to do so. Some preferred to wait for more people to show up, as the July 1 march from Victoria Park was due to reach the area late in the afternoon. But others said no. “They said those who wanted to be peaceful would only try to stop the rest,” said a 26-year-old protester who declined to be named. Some feared a delay would only allow the police to get prepared. University student Nick Yeung, 22, said: “We decided to occupy Legco and paralyze it to make the authorities face our demands.” Several had concerns about the legal risks, but such worries were brushed aside. “We didn’t discuss what would happen if we got arrested,” Yeung said.

It was around then that some in the group found a caged metal cart, and protesters began throwing poles and scrap metal items into it. Then, as about 40 police officers watched, they wheeled the cart toward the Legco building and started bashing it against the glass walls. Holding up umbrellas to shield themselves from cameras, they rammed the cart repeatedly against the glass. Others used makeshift weapons, including metal bars and rods, to strike the glass walls. Some threw bricks at the doors of the building, while others heckled police officers inside. Shouts of gar yau, “add oil!,” a common Cantonese refrain of encouragement, echoed through the area as protesters egged on those creating the chaos. Opposition lawmaker Leung Yiu-chung was seen trying to stop the protesters, but he was shoved aside and fell to the ground.

Others from the camp, including Roy Kwong Chun-yu and Lam Cheuk-ting, pleaded with the protesters to remain peaceful, but their appeals fell on deaf ears too. In one Telegram group with more than 20,000 members, some expressed disapproval. “What’s the purpose of smashing the glass?” asked one user. Others called on the protesters to stay united, with one saying: “If we manage to storm Legco, it means we have the ability to overthrow the government. Carrie Lam has been ignoring us because she thinks we are harmless. This is meant to tell Carrie Lam, ‘If you don’t respond to our appeals, we will tear down your house.’”

Inside the building, about 1,000 police officers stood on guard in full riot gear. Their warnings to the protesters were drowned out. At about 6pm, Legco issued a red alert, telling everyone inside the building to leave. Outside, there appeared to be some confusion among the protesters, with some appearing unsure about whether to enter. Moments before those in front finally breached the main entrance at 9pm, some protesters tried to dissuade them from entering, shouting: “Come back! There are police inside and it’s all locked down, there’s no point in storming! It will just send you to jail!”

In one part of the building, radicals succeeded in smashing a glass panel, creating an opening. Elsewhere, the main entrance and another section were breached. Despite their initial hesitation, the mob soon stormed the legislature. As an air horn sounded amid the clanking of metal on metal, they poured in, pumping their fists in the air. The ransacking of Legco was about to begin. Inexplicably, the riot police inside the building retreated. The vandals made their way through several floors, trashing furniture, smashing security cameras and television monitors, and spray-painting slogans on walls.

Finally, the group entered the wood-paneled Legco chamber and began wreaking havoc, as surreal scenes of the devastation wrought by the masked intruders were broadcast live on television. Some began covering the walls and columns with graffiti that read, among other things: “Dog officials”; “Down down, Carrie Lam”; “Carrie Lam, step down”; “Release the protesters”; “We want genuine universal suffrage”; and “Hong Kong is not China.” Many of these messages were familiar from the month of protests in Hong Kong. But there was a new line scrawled outside the chamber, as if to explain the day’s violence: “You taught me that peaceful protests are useless.”

The intruders were not done yet. As a canopy of umbrellas opened to shield the perpetrators from television cameras, some clambered over the Legco president’s seat and daubed it with black paint. Their target was the emblem of Hong Kong, the symbol of the “one country, two systems” principle. They blackened the image of the bauhinia at the center and smeared paint over the words “of the People’s Republic of China,” leaving only “Hong Kong Special Administrative Region” untouched. They tried to hang a British colonial flag over the emblem but, failing to do so, draped it across the president’s podium.

A mock funeral procession ensued, with a group holding black-and-white portraits of Carrie Lam, security minister John Lee Ka-chiu, justice minister Teresa Cheng Yeuk-wah and police commissioner Stephen Lo Wai-chung. They held up a banner that read: “There are no mobs, only tyrannical rule.” Remaining in the chamber and the antechamber, a resting area for lawmakers, the protesters tore up documents, including copies of the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s miniconstitution. Legco officials later reported that computer servers and hard disks had gone missing. The protesters said they had deliberately avoided damaging the library and left cash for drinks they had taken.

While the protesters succeeded in breaking into the Legco chamber, it soon became clear that they had no intention of remaining indefinitely, but had no exit strategy either. As the night wore on, there was uncertainty and confusion as some protesters urged those inside to leave. In the presence of journalists, they debated their next course of action. Four appeared determined to stay. Among them was 25-year-old graduate student Brian Leung Kai-ping. As an activist during the Occupy protests of 2014, which shut down parts of Hong Kong for 79 days, he had experienced firsthand the disappointment of seeing a movement fragment after failing to achieve its goals.

Now, in the Legco chamber, Brian Leung stood on the lawmakers’ desks and read out a manifesto later dubbed the Admiralty Declaration. The list of 10 demands included a call for democratic elections to give Hongkongers the right to choose their lawmakers and chief executive. At one point, he dramatically removed his mask – becoming the only one to do so willingly throughout the protests – and shouted: “The more people are here, the safer we are. Let’s stay and occupy the chamber, we can’t lose anymore.”

The storming of Legco played out on live television for nearly 12 hours. Leung and the last of his comrades in the chamber were finally carried out by other protesters. After issuing several warnings, about 3,000 riot police officers moved into the Legco compound and fired tear gas outside the building, but they made no arrests.

Leung fled the city the next day for the United States, where he is studying for a doctorate in political science. He said later: “The pursuit of freedom and democracy is fundamentally what drove hundreds of protesters into Legco that day. I volunteered to be in front of the camera to read out the key demands of protesters in the chamber. The last thing I wished was to have no clear demands put on the table.” He had been impulsive in removing his mask, he admitted, but called it “a beautiful mistake.” He said the protesters had to act to grab the attention of those in power as well as those in the movement, to register the accumulated frustrations of an unfair electoral system. “It is time to look past the short burst of ‘violence’, and read deeper into what people, particularly the younger generation, are really thinking,” he said.

At 4am on July 2, a grim-faced Carrie Lam appeared at a press conference at police headquarters to condemn the day’s violence, vowing to pursue those responsible to the end. Their actions had saddened and shocked a lot of people, she said, calling for their violence and vandalism to be condemned, as “nothing is more important than the rule of law in Hong Kong.”

The trashed Legco had to be closed. It was repaired during the summer, re-opening only in October 2019. The bill for the damage: HK$40 million (US$5.1 million).

— With reporting by Alvin Lum