Читать книгу Rebel City - South China Morning Post Team - Страница 49

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

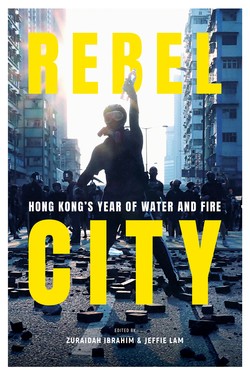

The takeover of Hong Kong’s airport

ОглавлениеVictor Ting

For five days in August, the city’s international airport, which has won the best airport title over 75 times, was crippled by a protest sit-in that ended in fisticuffs, tear gas and arrests.

In August 2019, Jack Lo sat for three days with thousands of others on the floor of the arrivals hall at Hong Kong International Airport, one of the world’s busiest aviation hubs.

The self-professed radical protester, 17, was exhausted from waving anti-government placards, handing out fliers and trying to explain to foreign visitors what Hong Kong’s anti-government demonstrations were about. He was also frustrated that despite the inconvenience, most travelers came and went, seemingly unaffected and indifferent. The government also appeared unmoved. And now there were rumors swirling that riot police were preparing to swoop in on the airport and clear out the protesters. On Monday, August 12, his fourth day there, Lo was impatient for real action that would make people around the world sit up and take notice. The way to do that, he was convinced, was for the protesters to move to the departure area and stop travelers from leaving. Lo thought to himself: “It’s now or never.”

He shared his views with the group of about 20 protesters around him, saying: “The clock is ticking. There is not a moment to waste.” Not everyone agreed that drastic action would work. Some asked, what if they only ended up alienating the international community? Lo held his ground, saying: “To have an effect, protests need to be disruptive and cause discomfort to some people and the status quo. We must up the ante and strike now, or we might as well pack up and go home.”

In his corner of the airport terminal, Lo succeeded in persuading his group. At 3pm that day, he led his squad to join thousands of other black-clad demonstrators who swarmed across the departure area, blocking distressed passengers and airline crew alike. The Airport Authority canceled all outgoing flights after 4.30pm. News of the chaos at Hong Kong’s airport, which generally handled 800 flights daily, swept across the world.

The airport first featured in Hong Kong’s protests on July 26, when hundreds of flight attendants and airport staff staged a sit-in at the arrivals hall. They wanted visitors to know what happened at the Yuen Long MTR station on July 21, when scores of white-clad men believed to have triad connections attacked train passengers and black-clad protesters wantonly, with police nowhere in sight. That protest passed peacefully.

On August 5, more than 200 flights were canceled when a record number of pilots, airport ground staff and other aviation industry workers called in sick and joined a citywide strike to press for the movement’s five demands, which included an independent probe into allegations of police brutality, as well as universal suffrage for Hongkongers. On Friday, August 9, Lo and thousands of others showed up at the airport for what was meant to be a three-day sit-in.

Hong Kong’s anti-government protests were in their third month, and elsewhere in the city, the weekend of August 10 and 11 witnessed some of the most violent clashes between hard-core radicals and police. As mobs rampaged across parts of Tsim Sha Tsui, Sham Shui Po, Wan Chai and Kwai Chung on Sunday, August 11, police responded with tougher tactics. That day, a young woman in the crowd at Tsim Sha Tsui was injured in the right eye, and protesters said she was hit by a beanbag round fired by officers. Police refused to take the blame before investigations were carried out, suggesting that she might have been hit by a projectile from a protester’s catapult. A photograph of the woman, with a bloodied patch over her right eye, rapidly became a symbol of alleged police brutality.

The airport sit-in should have ended that Sunday, but news of the woman’s injury sparked anger against police and moved tens of thousands of protesters to head for the airport on Monday and Tuesday, August 12 and 13. Many arrived on foot, bringing traffic along nearby roads to a standstill. Several wore eye patches, showing their solidarity with the injured woman. The worst of the airport chaos followed, especially after protesters occupied the departure areas. On Monday alone, more than 180 departures were canceled after 4pm with the airport hoping to resume flights from 6am on Tuesday.

But more disruption followed, effectively shutting down the airport for a second day. The impact was severe, with 421 flights axed. The airport unrest led to the cancelation of a total of 979 flights. Tens of thousands of travelers were stranded, and many were furious at having to scramble for accommodation or make alternative travel arrangements.

Some angry travelers accused demonstrators of acting “like the mafia.” Pavol Cacara, 51, from Slovakia, tried reasoning with some of those blocking travelers, but they shrugged him off. “They are turning public opinion against them,” he said. “Is it right to take away the freedom of someone else, when they are trying to fight for their freedom?”

Australian Helina Marshall burst into tears when her group of five could not leave. She said: “We have an old lady here, 84 years old, and she has heart problems. They can’t let her through, to go back home?” Her elderly companion, Barbara Hill, in a wheelchair, said: “I was sympathetic to their cause, but I think they are harming it by stopping passengers from getting through.” A Thai woman, comforting her son, ticked off protesters, saying: “You can fight with your government, but not me, understand? I just want to go home! We pay money to come to your country but you do this to us. We will never come here again!”

A few travelers made it through the blockade, including pregnant women and an official Hong Kong team of swimmers heading to Singapore for the FINA World Cup competition. Swimmer Leo Fung pleaded with protesters, saying: “We understand and support what you are doing, but we have qualified and hope to represent Hong Kong at the World Cup. There aren’t that many competition opportunities like this, and I hope you will let us through.”

Looking back on all that happened at the airport, protester Lo said in February 2020 that he had no regrets. “We were trying to get travelers around the world on our side, and at that point we needed a more radical course of action to grab international headlines, and we succeeded in doing that,” he said. Far from being apologetic for the inconvenience and damage done to Hong Kong’s international reputation, he said: “The airport occupation was a logical and natural progression from road blockades and rail disruption at MTR stations. They were all disruptive, but made a point.”

Mainland officials watching the increased violence on Hong Kong streets and the shutdown of the airport said it bordered on terrorism. Up until then, Hong Kong’s social movement had received scant coverage in mainland media. But two incidents of violence at the airport on August 13 – when two men wrongly suspected of being undercover state agents were assaulted – unleashed a storm of anger on the mainland against Hong Kong protesters.

The first man, Xu Jinyang, was surrounded and attacked twice, at 7pm and again at 9pm, after a group of protesters found wooden sticks on him and claimed that the name on his travel documents matched that of an officer from the Futian police station in Shenzhen. The young man told reporters he was from Shenzhen and was at the airport to see off friends who were traveling. He denied he was a public security officer. Protesters surrounded him, secured his hands with cable ties, and would not let paramedics move him after he lost consciousness at about 10pm. It was another hour before he was taken to hospital by ambulance, but there was more trouble outside the terminal as protesters turned on police who had come to help the ambulance leave. Police vehicles were attacked, their windows smashed.

After Xu was taken away, hundreds of protesters surrounded another mainlander inside the terminal, cable-tying his hands to a luggage trolley. They had found a light blue T-shirt in his backpack emblazoned with the slogan “I love HK police.” Only the previous week, on August 5, a mob wearing T-shirts bearing the same message had attacked protesters with sticks. Despite being detained, the man, later identified as Fu Guohao, smiled and calmly told the mob in English and Cantonese: “I support Hong Kong police. You can beat me now.” Enraged, one protester poured fluid from a bottle over his head, while others punched, kicked and hit him with umbrellas. Fu turned out to be a journalist for the Chinese nationalist tabloid Global Times.

At the scene was lawmaker Fernando Cheung Chiu-hung, from the pan-democratic Labour Party. He had shown up to try and mediate between the protesters and police. As Fu was being attacked, Cheung urged the angry crowd to stop the violence, but they ignored him. Fu’s ordeal lasted about an hour before he was rescued by dozens of riot police and taken away by ambulance at about 12.30am with scratches on his face.

Recalling that day’s chaos, Cheung said in February 2020 that he thought the airport occupation was a good tactic to force the government’s hand. “And if the government took a wrong step, it would be a global humiliation and blunt their legitimacy to govern. I went there expecting to prevent aggressive police action,” he said. “When I got there … tempers were frayed and the air was thick with tension … Of course, as a believer in peaceful protests, I don’t agree with violence. But I can understand why the protesters were angry and did what they did.”

The events at the airport that night brought police into the terminal building. Officers were seen rushing in and subduing some protesters, with injuries reported on both sides. In a late-night chase that lasted about 15 minutes, protesters threw bins and water bottles at police from behind barricades fortified by baggage trolleys, while officers used batons and pepper spray on them. At one point, some protesters grabbed an officer’s baton and began striking him with it. He responded by drawing his gun and pointing it at them, an act criticized by protesters as being disproportionate and dangerous, but defended vigorously by police as an appropriate act of self-defense.

On the mainland, it was the attack on journalist Fu that drew the biggest response. Chinese social media was awash with vitriol against Hong Kong’s protesters and praise for Fu, who was hailed as a hero for standing up to his attackers. The hashtags “Fu Guohao is a real man” and “I also support Hong Kong police” spread like wildfire on Weibo, China's largest social media network. “The injuries on his face reflect the injuries in the hearts of all Chinese people,” read one of the most popular comments. Another asked: “How many Chinese will have sleepless nights? Our state power should take action now!” Fu’s provocative challenge to the protesters – “You can beat me now” – was even immortalized on a T-shirt, which sold for 98 yuan on online shopping platform Taobao.

The Hong Kong protests, which had been off-limits and a heavily censored topic on Chinese social media, suddenly burst into the open, amplified further by the mainland’s mainstream media. People’s Daily, the Communist Party’s mouthpiece, praised Fu’s “manliness” and said in a Weibo post shared widely: “Let’s remember Fu Guohao and his awe-inspiring righteousness while being held. This is what a dignified and upright Chinese should be like.” The two mainland men attacked at the airport were discharged from hospital the day after. Fu told supporters as he left the hospital: “In Hong Kong, I complied with everything a citizen should do. I didn’t do anything unlawful or behave in a way that would stir controversy. I think I should not be treated violently.”

Reflecting on the outpouring of emotion on the mainland, lawmaker Cheung said: “I read some of those comments online and thought there was palpable anger in some unfamiliar quarters, not just the usual nationalist types. The effect was certainly to turn or silence those originally sympathetic to the protests. The Fu incident definitely showed that the propaganda machine went into overdrive to whip up nationalist fervor.”

As protesters and police clashed at the terminal building on August 13, the Airport Authority went to the High Court and obtained an interim injunction to ban unlawful and wilful obstruction of the proper use of the airport as well as the roads and passageways nearby. It prohibited people from “inciting, aiding and/or abetting” such acts, and confined any demonstrations to two designated areas at either end of the arrivals hall. Flouting the injunction would amount to the criminal offense of contempt of court, with a penalty of a jail term and fine. The injunction was the first in the ongoing anti-government protests, and drew some criticism as an abuse of the legal process.

But Victor Dawes, the Airport Authority’s lead counsel, who had the order extended indefinitely a week later, said: “An injunction, unlike the by-laws of the Airport Authority, carries with it the express authority of the courts, and therefore may command higher respect and compliance among the general public.” He rejected the suggestion that this was an abuse of the law, saying protesters or other relevant groups could argue their case in court. No legal challenge was filed.

Others, including businesses, welcomed the move. The Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, the city’s largest business group, supported the airport’s injunction application to boot out protesters. “Left unaddressed, the closure of the airport would have seriously tarnished Hong Kong’s reputation and role as an air transport hub for the region,” it said.

The five days of the airport occupation ended on Tuesday, August 13. The next day, hundreds of protesters were back, this time to say sorry for causing the flight cancellations and inconvenience to travelers. A hand-written sign, one of many with similar messages, said: “Dear tourists, we are deeply sorry about what happened yesterday. We were desperate and made imperfect decisions. Please accept our apology.”

There were no references to the two mainlanders who were attacked, but a statement issued by “a group of fellow Hongkongers longing for freedom and democracy” said the overreaction of some protesters left them feeling heartbroken and helpless.

The administration team of the Telegram encrypted messaging group for the airport sit-in, which had close to 40,000 members, posted a message too, saying: “What happened on Tuesday is not perfect, but it does not mean that the sit-in is officially terminated. What we need to do now is to look forward, to maintain confidence in ourselves and our peers, to reflect on our deeds, and to believe that we will perform better next time.” Internet users had fierce debates on the LIHKG online forum – the de facto virtual command center of the protest movement – with some saying they should reflect on their strategies to win back public support. At the airport, protester Spencer Ho, 39, a salesman, distributed food to passengers. A placard on his trolley read: “We were desperate. Please accept our apology.”

Looking back at the airport protests, lawmaker Cheung said: “It was definitely a watershed moment because radical protesters felt more able to push the envelope afterward and see how much they could get away with.” He said the protesters’ motto to stay united with the more extreme elements within the movement also sowed the seeds for more violence to come.

After Wednesday, August 14, few protesters continued to stay at the airport while others moved their battlefield to nearby towns like Tung Chung over the next few weekends. Over the weekends that followed, they tried to block access routes to the airport, including throwing rods and metal objects at the railway tracks of its express train line. On September 1, travelers were stranded for hours at the airport or forced to lug their suitcases and walk at least 15km on a highway to find transport into the city. Protesters tried the same tactics again in subsequent weeks, but with little success.

To date, the airport remains a tightly controlled facility with passengers required to present their boarding pass at barricaded entrances, their family and friends generally barred from entering the building.

But while the protests there came to an end, Lo dismissed the suggestion that occupying the terminal building was a failure. “Victory comes in many ways, shapes and forms,” he said, adding that the episode taught the movement to harness its firepower and hone its mobilization skills for other action, including the occupation of the Polytechnic University campus in November 2019. “We can lose one battle to win the war. We are in this for the long haul,” he said.