Читать книгу Rebel City - South China Morning Post Team - Страница 48

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

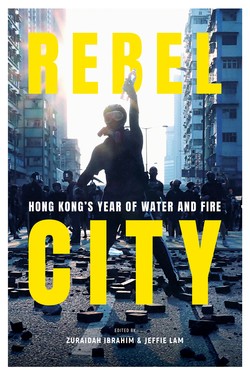

Protests, clashes in the city, violence in Yuen Long

ОглавлениеThe Yuen Long incident occurred while anti-government protesters were locked in pitched battles with riot police in the heart of the business district on Hong Kong Island. That Sunday afternoon, organizers estimated that 430,000 people had gathered to march from Causeway Bay to Wan Chai. Most were dressed in black and wearing masks. The protesters made their way to Sai Ying Pun, where radicals on the front lines broke away and laid siege to Beijing’s liaison office, throwing eggs and smearing the national emblem. It was to be a long night of clashes, with riot police firing rounds of tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse the crowd.

The trouble in Yuen Long was not entirely unexpected. From Sunday evening, word spread over social media that a crowd of suspicious-looking men wearing white T-shirts had gathered in the town, near Fung Yau Street East. Johnny Mak Ip-sing, a Yuen Long district councilor, said that he had filed a police report and had alerted a local sergeant to what he saw at about 8pm. In the city, protesters began receiving messages warning them not to get off at Yuen Long railway station if they were heading home to the New Territories. They were also advised not to wear black. At Central MTR station on Hong Kong Island, protesters left stacks of clothes of every color at the ticket machines, with written notes telling those going to Yuen Long to change out of their black protest gear.

In Yuen Long itself, a message had spread the day before, advising residents not to wear black. Villagers in the district said afterward that rural leaders advised them to avoid going out on Sunday. It emerged later that Li Jiyi, director of the Beijing liaison office’s New Territories branch, had urged Yuen Long villagers to protect their towns and drive away any protesters, during a community banquet held 10 days before the attack.

As word of imminent trouble in the town spread on Sunday evening, Democratic Party lawmaker Lam Cheuk-ting, who was at the protest on Hong Kong Island, decided to leave for the New Territories. He made his way to Mei Foo station, a mid-point between Hong Kong and New Territories West, a short distance from Yuen Long. Not long after arriving at Mei Foo, one of his companions received a video clip showing chef So being attacked. He got on a train heading for Yuen Long. “I called a police community relations officer at 10.22pm asking him to stop the attack, and was told that plainclothes officers had already been deployed,” Lam recalled afterward. “I also urged him to keep an eye on Long Ping and Yuen Long railway stations and he promised to pass the message to his seniors.”

The moment the train doors opened at Yuen Long station, Lam heard a young man crying out for help. He was shocked by the scene unfolding before his eyes. The white-clad mob was beating anyone they came across with rods and rattan canes. There was blood on the floor, and broken sticks scattered everywhere. As the attackers charged into the paid area of the station, alarmed passengers yelled: “Don’t come in!” People tried protecting themselves with unfurled umbrellas, and grabbed children to shelter them. Some called out to others to avoid provoking the uncontrollable mob, as a group chanted defiantly at their attackers. A few tried to fight back using a fire hose and an extinguisher from the station, but they were overwhelmed as the white shirts stormed toward the platform.

Passengers inside the train began screaming as they realized what was happening. The attackers struck the passengers for about 10 minutes. Video footage, captured by others in the carriage using smartphones, showed a man kneeling at the train door, imploring the mob to stop. Women were seen standing on their seats, pleading for mercy.

“Please don’t beat us, I beg you,” one woman cried out.

“I’m only trying to head home after a day’s work,” said another.

“We are just civilians,” cried a third woman.

Then the MTR made an announcement declaring services suspended and asking everyone to leave the train. But people refused to leave, fearing they would be attacked on the platform, where there were more men wearing white, armed and masked. It was past 11pm when the train driver, responding to passengers’ pleas for help, pulled away from the platform once the doors could close. The railway operator explained later that initially the driver could not see what was happening and was only aware that the doors were blocked.

Video clips began circulating online and on television, showing the chaos as frightened passengers scrambled for cover. Lawmaker Lam, who posted live video footage over Facebook, was also attacked and needed 18 stitches for injuries to his mouth. Throughout the entire ordeal, police did not show up. Vincent Lo, a fourth-year university student, said that at about 10.30pm he saw a large crowd of armed, white-clad men outside the station and called 999. “The officer noted my request coldly and, only when I asked, said police would arrive in 10 to 15 minutes,” he recalled afterward. “That, to me, seemed too long. It was totally unreasonable that they arrived only at 11.20pm.”

Other witnesses, as well as the management of Yoho Mall, which is linked to the station, said they tried to call but could not get through to police. The force explained later that its New Territories North call center was overwhelmed by hundreds of emergency calls between 10pm and midnight that day. Responding to criticism of the force, then police commissioner Stephen Lo Wai-chung said two officers arrived at the station at 10.52pm, seven minutes after they received a report about the violence, but they called for reinforcements when they realized that they did not have enough protective gear. The force was mocked when a photograph showing two officers walking away from the scene of violence and chaos was shared widely.

A police source defended the officers’ actions, saying several weeks of mass rallies and protest violence had put a serious strain on the force’s manpower and resources. To deal with that Sunday’s mass march on Hong Kong Island, he said, all five police regions had to send manpower to help. He said there was a series of emergencies happening in Yuen Long at the same time that evening, and the district police did not have the resources to deal with them all. When violence broke out at the train station, officers from the Emergency Unit, whose vehicles are equipped with anti-riot gear, were dealing with other incidents such as fights, assaults and a fire in the district. More than 500 officers from a regional response contingent, who were in the midst of clearing protesters in Sheung Wan, Hong Kong Island, had to be redeployed to Yuen Long.

When more than 30 officers finally arrived at the scene, it was 11.20pm and most of the thugs in white were gone. “I saw a lot of people in white shirts running right past police, and they did not even stop them,” a witness said. An angry crowd, joined by local residents who had rushed out after finding out about the violence on the news, surrounded the officers. Some hurled profanities at the officers, while others shouted: “Where have you been? You are supposed to protect us. Why are you allowing those men to leave so easily?” Police’s explanation was that the officers did not see anyone breaking the law when they arrived and could not arrest people just because of the color of their clothes.

A second round of violence occurred at about midnight, after more than 200 people confronted a group of men in white who had gathered near the entrance of Nam Pin Wai, a village next to Yuen Long station. Police officers soon arrived to investigate. Some of the men in white retaliated by throwing various objects at dozens of protesters standing on the staircases outside the station exit. The alarmed protesters were forced to retreat into the station, where they banged desperately on the window of the station’s control room, urging MTR employees to shut the gate of the exit. The staff eventually did so. About two dozen of the white-clad men then appeared at the gate, forced open the shutters and rushed into the station. The trapped protesters fled toward Yoho Mall through another exit, but those who could not get away quickly enough were attacked. Once again, there were no police officers in the station when the white gang struck.

Meanwhile, some white-clad men emerged from Nam Pin Wai and chased a group of protesters down a street. A man wearing a dark shirt was seen being hit over the head with sticks, resulting in bloody injuries. Several white-clad men armed with clubs smashed several cars, whose drivers had come to pick up protesters and other train passengers stranded in the area. At 1am, a team of about 100 riot police officers went to the village, where many men in white were gathered, but again no arrests were made. Police said they did not find any weapons or come across anything suspicious.

The Yuen Long incident remained a sore point for months afterward, with angry protesters gathering at the scene on the 21st of every month to criticize the police response that day and demand an independent probe into the force’s handling of events. The Independent Commission Against Corruption, the city’s graft-buster, began investigating whether any police officer was guilty of misconduct.

Questions lingered over the mob in white. Pro-establishment lawmaker Junius Ho Kwan-yiu found himself in hot water when a video clip showing him shaking hands with men in white T-shirts in Yuen Long that Sunday night circulated widely online. Speaking to the media the following day, Ho enraged many when he defended the mob involved in the attack, saying they were merely “defending their home and people.” As for the men he was seen shaking hands with, he said: “Some of them I know, some are village chiefs, teachers, shop owners and car mechanics.” He said that it was just a coincidence that he happened to be in the neighborhood. “I live in Yuen Long, so it is normal for me to be there,” he said. Ho denied that he had known about the attack in advance or that he had any role in it. Instead, he accused lawmaker Lam of “leading protesters to Yuen Long.”

Over the days that followed, police arrested a total of 37 people – some with links to triads – for their alleged roles in the violence. As of January 2020, seven had been charged with rioting. Months after the event, police said they were still collecting evidence. Despite the arrests, lawmaker Lam was unsatisfied that none of those charged was believed to have organized the violence. He and seven other victims, including chef So, filed a lawsuit against the police commissioner, seeking a total of HK$2.7 million (US$350,000) in compensation. Lam said the Yuen Long attack proved a watershed for the protest movement. Accusing the police of colluding with the gangsters that day, he said: “They have lost their credibility.” The distrust fueled a worrying trend of vigilantism, he noted, as protesters involved in clashes with rival groups began preferring to “resolve matters privately.” “They used to ask lawmakers to mediate and reported to police only if disputes could not be solved, but not after July 21,” he claimed.

Police chief Lo categorically denied the suggestion of collusion between his officers and the Yuen Long attackers, but the force was put on the defensive. Senior Superintendent Kelvin Kong Wing-cheung said in January 2020 that the trouble that night was caused by “a group of people who led some protesters to Yuen Long.” But who were they, what did they want, and who was behind them? Those questions remained unanswered, continuing to provide protesters and opposition lawmakers alike political grist for criticism of the police force.

The white-shirt attack also affected residents in the area for months afterward, with people preferring not to stay out late at night and businesses reporting that they were hit too. A popular beef brisket restaurant in the area claimed that its monthly revenues were halved in the wake of the incident. “We used to target diners who return late from work, but now many choose not to eat out and head home as early as they can,” its owner, surnamed Hui, said. “Who is to blame for the fear?”

— With reporting by Clifford Lo and Natalie Wong