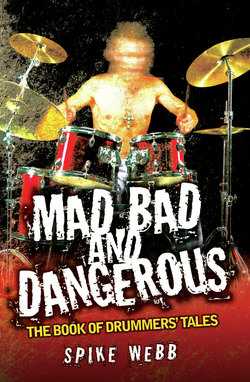

Читать книгу Mad, Bad and Dangerous - The Book of Drummers' Tales - Spike Webb - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

MIRROR IN THE DRESSING ROOM

ОглавлениеWhen it comes to drummers from the punk era, Topper Headon is the man. Drafted into The Clash when original drummer Terry Chimes left after recording the first album in 1977, he stayed with the group right through their heyday until his controversial departure in 1982. I met him in his hometown, Dover.

So, the band is The Clash. The venue is a big one, somewhere in Holland. Mick Jones, Paul Simonon and Joe Strummer are crowded round the one mirror in the band’s dressing room, taking it in turns to do their make-up and, in particular, their hair. Topper enters the room and asks if he can borrow the mirror. The rest of the band figure he must be in a hurry so they stand aside. Topper walks casually up to the mirror and makes to adjust its positioning. Just as the guys are wondering why he’s taking such trouble over his hair on this particular night, Topper lifts the mirror from the wall and places it carefully on the floor. He then produces a bag of white powder, deposits a generous amount onto the mirror surface and snorts it up his nose in seconds flat. He then places the mirror back on the wall, adjusts his hair and leaves the room saying: ‘Thanks guys! See you on stage…’

What you might call rock’n’roll. But as Topper will now tell you, that’s debatable. The rest of the band certainly held a debate about it, resulting in Topper’s eventual parting company with The Clash. It’s not that snorting coke was frowned upon by rock musicians in those days; quite the contrary in fact. Certainly, the excessive use of drugs and alcohol as a way to wind up and down from gigs as part of a rock lifestyle was, and for some people still is, totally acceptable.

The problem was that, like many people, Topper found himself spiralling out of control. And that’s ever so easy when you’re famous, the gigs are huge and the schedule is gruelling. Of course, in the early days it’s fun to use a little extra stimulant to ease your way in and out of the proceedings.

Imagine. It’s a local pub in London. Call it The Stapleton Arms. You are a drummer in a band about to play a one-hour set on a Friday night. The place is heaving with your own supporters plus a generous sprinkling of pub locals. Your kit is set up and you’ve just glanced over the set list before taping it to the side of your bass bin. As always at these popular gigs, you’re a bit jittery, so you’re enjoying a few pints to calm your nerves. It helps to relax you into the right mood – a combination of cool but raring to go.

The gig goes well, the crowd roar their approval and you come off the tiny stage pouring with sweat, just the way you like it. Now you’re really wound up and buzzing, so you need to do something to relax. A couple of mates (unpaid roadies) are dismantling your drum kit, so you’re free to enjoy a few more drinks and chat with the rest of the band and entourage. This turns into a bit of a party and before you know it, you’re back at someone’s flat with some takeaways in the small hours (who knows, you might even get your leg over later).

And so it goes with most gigs. At that level it’s fine, because you’re not playing enough for the partying side of it to really take over your life. You’ve probably got a day job to hold down to pay the rent, take care of drum repairs and provide you with spending money so you can party after gigs!

The real problems begin when it becomes your job.

As Topper says: ‘At first it’s great because every gig is an event and a party. Soon drugs are added into the mix. That makes you think you’re playing even better but after a while you realise you can’t actually play properly unless you’ve taken drugs. I was on all sorts; cocaine, smack as well as the booze. I’d have to get into a certain state before I played. Then it got to the stage where the drugs were more important than the playing.’

Of course, if you’re the official band nutter it doesn’t help matters: ‘The rest of the band already had their specific image within the band: Paul was the good looking one, Mick was the sensitive songwriter, Joe was the James Dean rebel, which left me with the role of crazy lunatic drug-taking drummer. A role which I lived up to fairly well, I think…’

Nevertheless, being the crazy drummer didn’t stop Topper writing the band’s biggest hit: ‘I arrived one day for a recording session at Electric Ladyland to discover I was the only one there. Nothing unusual about that, the others were always late. I started messing around on the keyboard with a tune I’d had knocking around in my head. I thought it sounded pretty catchy so I recorded it. Then I put a bass line down. Still nobody else had turned up so I put down some guitar parts. By the time the rest of the band arrived I’d got most of the song in the can. Joe went off to the loos to write some lyrics and an hour or so later the song was complete.’

‘Rock the Casbah’ became The Clash’s biggest-selling single, although probably not the most popular with Clash fans. Nobody really knew it was mostly written by the drummer but, hey, he’s still living on the royalties to this day.

In 1986, Topper released a solo album for the Mercury label entitled Waking Up. It was all about how he had at last kicked his drug habit and the new life he was enjoying after finally getting clean. The public saw it as the record of a man who had won his battle with drugs, having fought his demons for most of the latter part of his drumming career. Not so. Topper had, in fact, recorded the album in order to raise money to buy more drugs. Six months later he was in prison for dealing heroin.

Topper had begun taking drugs to play music. Somewhere down the line, without him even noticing, everything had turned around. Now he was playing music to take drugs. At one stage it got so bad that Topper actually hit the streets, busking and living in hostels for the homeless.

‘I remember standing in a queue at a soup kitchen, shuffling towards the counter with my fellow down-and-outs and thinking, “I’m Topper, I was the drummer with The Clash, one of the biggest bands of the ’70s and ’80s, I played in front of 80,000 people at Victoria Park, I had roadies, I had hotels, I had limos, I had money… and I wrote ‘Rock the Casbah’!”’

It’s now early autumn 2007, and I’m talking to Topper on a park bench near his home in Dover, where he grew up. He is now completely clean and sober, having completed an 18-month course of chemo-drugs to cure the hepatitis B he had contracted during the drug days. This time he really has kicked it. He still plays drums, when he wants to, not when he feels he has to. And he enjoys it more than ever.

As our chat comes to a close, I touch upon the reputation drummers have for being mad. He feels that, at the end of the day, there has to be some truth in it: ‘Think about it. Other would-be musicians opt for something that can produce a melody, something that can give you reasonably pleasant results in a relatively short time as you learn. As a drummer, it takes about a year before you stop sounding dreadful and upsetting people. You really have to persevere at it to become even bearable to listen to. It’s aggressive and it’s anti-social. Considering the barbaric nature of the instrument, you’ve got to be a bit different from other people to want to do it for any serious length of time. You’ve got to be a certain type of person to play the drums.

‘You have got to be a bit mad, in fact.’

World-class drummer Steve White, however, takes another viewpoint.

‘Mad? No way,” says Paul Weller’s long-standing stick wielder. “Drumming is the most spiritual, soulful instrument a person can play. Rhythm is part of the very basis of human life. It relates to our heartbeat and our sense of equilibrium.’

Our sanity, in fact?

But there is one drummer who has gone down in history as the definitive madman – someone who spent much of his spare time shocking the media and those around him with outrageous stunts and practical jokes.