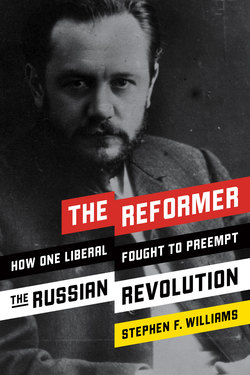

Читать книгу The Reformer - Stephen F. Williams - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

Friends and Lovers

MAKLAKOV WAS GENERALLY gregarious—obvious exceptions being the forced march to his law degree and his fateful neglect of his friend Nicholas Cherniaev. His friends included some relatively well-known Russians, of whom Tolstoy is by all odds the best known; and the archives include records of his romantic interests, some of whom were prolific letter writers.

He knew Anton Chekhov, and although he saw him at least once at the Tolstoys’, had known him before then. Among their bonds was the Zvenigorod area, where Maklakov owned hunting and fishing land and where Chekhov had lived as young man. Chekhov in fact looked for a country property near Maklakov’s, but, as he reported to Maklakov, the place he visited proved overpriced.1 When Chekhov came to meet Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana, the Tolstoys’ country estate, Maklakov happened to be on hand. Chekhov arrived on a morning train, and Tolstoy, who usually wrote in the morning, excused himself and asked Maklakov to show Chekhov around. After the tour, the two writers began to chat. Chekhov gave Tolstoy an account of his trip to Sakhalin to study the penal colony there. He had traveled through Siberia to reach Sakhalin, and Tolstoy somewhat oddly responded to Chekhov’s Sakhalin account by rhapsodizing about the miraculous grandeur of Siberia’s mountains, rivers, forests, and animals. Chekhov agreed, and then Tolstoy asked, with surprise and some reproach, “Then why didn’t you show it?” After breakfast, Chekhov shook his head and said to Maklakov, “What a person!”2

Maklakov and Olga Knipper, Chekhov’s wife. © State Historical Museum, Moscow.

Maklakov also knew Maxim Gorky, presumably through his (Maklakov’s) stepmother; Maklakov was evidently a prototype for one Klim Samgin, the main figure in a four-volume Gorky novel that is now largely forgotten.3 Maklakov was also a friend of the great opera singer Fyodor Chaliapin. The origins of their meeting are unknown, but it may have stemmed from Maklakov’s defense of Nikolai and Savva Mamontov in a securities trial,4 Savva being a wealthy backer of Chaliapin. When Chaliapin was dying in Paris in the 1930s, Maklakov was a frequent visitor, entertaining him with the latest political gossip.5

Chapters 1 and 2 mentioned Maklakov’s first meeting and early contacts with Tolstoy. Their friendship, together with Maklakov’s reading of his literary and philosophical works, provided the background for several lectures Maklakov gave after Tolstoy’s death devoted to Tolstoy’s thinking and life and their role in Russia and the world. All the lectures look at Tolstoy both from the outside, as any scholar of Tolstoy might, and from the inside, as Tolstoy’s much younger and much less renowned friend. Maklakov never hides either his profound analytical disagreement with Tolstoy’s views on political economy, or his reverence for Tolstoy as a man of conscience.

Postcard from Vasily Maklakov on vacation with friends in Vichy, France, to his sister Mariia. Vasily is on the extreme left; Fyodor Chaliapin, the opera star, is third from left. © State Historical Museum, Moscow.

The pivotal lecture is the one on Tolstoy’s “Teaching and Life,” delivered in 1928 at a celebration of the centenary of Tolstoy’s birth.6 It tackles the origins of the philosophic outlook that Tolstoy had embraced by the mid-1880s, expressed in What I Believe (published in 1884) and summarized in the idea that evil must never be resisted with force. Maklakov himself appears to have been an agnostic. Letters he wrote near the end of his life reveal that he was at one time a believer and found his belief comforting; at some point he lost that belief and recognized that only genuine belief could provide consolation.7

Maklakov starts with the obvious truth that Tolstoy enjoyed all the rewards that the world can offer—nature gave him bodily strength, health, strong passions, ardor for life, and extraordinary literary gifts. Fate brought him wealth and allowed him not to worry about what the next day would bring or to bother with anything not fitting his taste or spirit. It gave him exceptional ties to the world and rewarded him with glory not only in Russia but throughout the world. It gave him, “as a crown,” exceptional family happiness. Yet, as Tolstoy made clear in his philosophical writings, the prospect of death led him to believe that life was meaningless, to the point of tempting him to suicide.8

After some false starts toward a solution, Tolstoy found one in the core message of the Sermon on the Mount—not to resist evil with force, but to turn the other cheek. For Tolstoy, this rule of nonresistance to evil was not part of a system involving life after death, and it was not a rule whose force depended on Christ’s being God. Indeed, Tolstoy often said (here Maklakov is presumably giving an eyewitness account), “If I thought of Christ as God, and not human, Christ would lose all appeal for me.” He read the gospels as not promising eternal life, as not contrasting a temporary individual life with an immortal individual life. Rather, the contrast he saw was between an individual life and a life lived entirely for others. When our personal life truly turns into a common life, he reasoned, the meaninglessness of life disappears, and a new meaning appears that no individual death can destroy.9 In his memoirs Maklakov tells a story reflecting the intensity of Tolstoy’s belief. In a conversation about not resisting evil, the wife of Tolstoy’s oldest son (Sergei) asked Tolstoy whether, if he saw some attempt to violate his wife before his very eyes, he wouldn’t intervene to protect her and feel sorry for her. Tolstoy answered that he would feel even more sorry for the rapist. Everyone laughed, and Tolstoy was quite angry, as he had not intended it as a joke, but really meant that someone who acted that way must be doing so from a very deep unhappiness.10

Maklakov’s speech, though mentioning a theological critique of Tolstoy by biblical scholars, presses a practical argument—that if neither individuals nor the state are to resist evil with force (where forceless resistance would fail), evil will triumph. He points out as an example the vandalization of a Tolstoyan settlement that he experienced during his university years.11 He then turns around and defends Tolstoy’s perspective. He asks rhetorically: If you think that property prevents us from turning individual life into a common life, and regard individual life as meaningless under conventional worldly conditions, then is there anything strange in nonresistance to evil, in “voluntarily giving away that odious private property to anyone who might want it?” Thus, Maklakov reasons, any refutation of Tolstoy must be directed not at his conclusions but at his original starting point. If you accept Tolstoy’s premises, a renunciation of force seems to follow.12

As the lecture and Maklakov’s memoirs underscore, Tolstoy’s basic kindness and common sense seem to have prevented him from following his own views with any consistency. In his memoirs Maklakov recounts how, on his return from his first trip to England, he gave Tolstoy an enthusiastic account of English government. Tolstoy was dismissive, saying that in principle there was no difference between English government and Russian autocracy. The conversation occurred at a time when the Dukhobors in Russia, members of a religious sect that rejected military service (on rather Tolstoyan grounds), had been subjected to ruthless oppression, including dispersal from their villages and forced resettlement, with the predictable result of widespread deaths from starvation and exposure. Tolstoy had responded actively, moving heaven and earth to help them migrate to Canada, raising funds, trying to stir public opinion, and giving them the proceeds from his novel Resurrection. Maklakov posed the obvious question: how could Tolstoy reconcile his indifference to the advantages of British government over Russia’s autocracy with his making all these efforts? Tolstoy said, “Ah, lawyer, you’ve caught me.” But then he added that the difference between the two was like that between the guillotine and hanging. In fact, from his perspective the guillotine was worse, because its evil was better concealed.13

The inconsistencies go on and on. Tolstoy energetically promoted the “single tax” ideas of Henry George, pressing the case in a letter to Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin and urging Maklakov to introduce George-type legislation in the Duma. Such legislation would tax away the entire value of unimproved real estate (and the value of improved real estate not directly attributable to improvements). The state would thus confiscate that value and wipe out the real estate market as a source of information about development prospects (through the signals given by market prices). The foe of all state power advocates a monumental exercise of state power!14

But Maklakov stressed Tolstoy’s efforts to improve the lives of ordinary Russians, however inconsistent some of the efforts might have been with his philosophy: writing Russia’s first alphabet books; writing the first works for children that rose above dreary, implausible celebrations of contemporary Russian life (a leading “reader” was a book called “Milord,” with about zero resonance for a peasant child); actually operating schools in the vicinity of Yasnaya Polyana and teaching in them; and, of course, relieving the 1891 famine and rescuing the Dukhobors. Maklakov observes, “His activity for his country was such that if ten people had done it, rather than Tolstoy, one could say of each that they had not lived on earth in vain.”15

Beyond these direct practical benefits, Maklakov pointed to a subtler, perhaps more far-reaching one—the way Tolstoy’s teachings reminded people of the independent force of good. If his readers were skeptical on practical grounds, if they “held back from following his conclusions, like the rich young man in the Gospels, all the same they started to look on the problems of life with different eyes.”16

And by raising questions about the meaning of life, Maklakov argues, Tolstoy—though excommunicated and buried without a funeral service—did more for the revival of religious interest than anyone. The danger to religion, he suggests, is not from those who deny it or even those who persecute believers, nor from the slogan that it’s an opiate, nor from the propaganda of the godless. Rather, the danger comes from indifference, from lack of interest in the questions with which religion deals. And Tolstoy couldn’t live without answers to those questions.17

The intellectual divide between the two was most acute in their views of the law, discussed by Maklakov in a lecture on “Tolstoy and the Courts.” After laying out Tolstoy’s belief that the state’s exercise of force was itself evil (regardless of the net effect on evil), Maklakov points to the radical character of Tolstoy’s objections. Tolstoy did not especially condemn the courts’ form, their incompleteness, the inadequacies of their procedures, the cruelty of punishments, or judicial mistakes; rather he condemned the very principle of their existence. He saw Christ’s famous instruction “judge not, that ye be not judged” as forbidding the very institution.18 That attitude toward law, and even the rule of law, was very much aligned with the views of Russia’s literary elite discussed in the Introduction.

Tolstoy not only condemned the courts as organs of state violence but also saw them as worse than more generally suspect institutions. The evil perpetrated by an executioner is obvious. But everything conspires to mask the evil of the judge. The judge who condemns someone to death doesn’t carry out the sentence; it is not he who deprives the person of life, but the law; if the law is bad and unjust, that is not his concern—or so Tolstoy assumed!19 Maklakov cites Tolstoy’s story, “Let the fire burn—don’t put it out,” observing that he could confidently quote passages of it from memory “because it was under the scrutiny of the censor so many times.” The cause of the censor’s hostile gaze was the story’s seeming exaltation of criminal acts: one character’s unlawful concealment of another’s crime is depicted as fulfilling God’s law.20

In his literary treatment of the courts, Tolstoy sometimes spoke not as a prophet inveighing against any state application of force but as a political figure and revolutionary. In Resurrection the law serves only to advance the interests of the ruling elite. This of course is a much more worldly message; as Maklakov observes, he is “speaking our language, addressing our concerns.”21

Lawyers fare even worse than courts under Tolstoy’s gaze. As the judge is worse than the hangman, because he can hide his guilt behind his role, so the lawyer is even worse than the judge, because he can even more persuasively distance himself from the evils wrought by the courts and the state. In his memoirs Maklakov recounts three occasions on which Tolstoy received lawyers at Yasnaya Polyana. The three lawyers (Oscar Gruzenberg, N. P. Karabchevskii, and Fyodor Plevako) were all very distinguished and often active for the defense in political trials; at the Beilis trial they and Maklakov constituted the defense team (with the exception of Plevako, who had died by then). Yet, except for Maklakov’s special friend Plevako, they irritated Tolstoy with their thinking process and attitudes.22

Maklakov, of course, had dedicated his life to law and politics, activities that he believed would advance the welfare of Russians. He exalted the courts as guardians of the law. He concludes with another mention of Tolstoy’s many actual efforts at improving life in this world, calling the relation between his beliefs and his life “an inconsistency, a touching, miraculous inconsistency.”23

Through his work on the 1891 famine, Maklakov met Tolstoy at his home in Moscow and talked with him for the first time.24 Tolstoy read his guests an article, and “everything seemed so natural and simple that I had to force myself to understand my good fortune and grasp where I was sitting. His wife, Sofia Andreevna, . . . called us all to the dining table.” After that he was often at the Tolstoys’ home, until Tolstoy’s death.25 “It was great luck for me. The whole world knows Tolstoy’s literary work. Some know his religious thinking, often only in part and not fully understanding it. To know the living Tolstoy, to experience his charm oneself, was given to very few.”26 Most of what follows as to Tolstoy’s character is drawn from Maklakov’s direct knowledge. Here is his overview:

For those who knew Tolstoy, there was no personal pride; on the contrary, no one could miss his dissatisfaction with himself, eternal doubt in himself, his touching shyness, his reluctance to dazzle, even his inability to play a leading role. . . . In Tolstoy everything was ordinary and simple. He never imposed on others the innermost principles by which he lived, never made them the subject of general conversation. If someone not knowing who he was should by chance find himself in his presence, he would not guess who was before him; he could not believe that this simple and kind old man, listening with such interest to the general conversation, was the very Tolstoy whom the whole world knew.27

Despite Maklakov’s own conviction that Tolstoy’s self-effacement was genuine, he recognized that it might seem a contrivance. As he notes, it put Tchaikovsky off when he met Tolstoy—simply, argues Maklakov, because of the mismatch between the real Tolstoy and the grand image held by the world at large.28

Maklakov was present at Tolstoy’s last departure from Moscow for Yasnaya Polyana, from which he then started on the journey that took him to his deathbed at the railway station in Astapovo. The newspapers had carried word of the departure, and the square in front of the railway station was packed. Everyone rushed toward the carriage that was bearing Tolstoy and his wife and daughters to the station, and the Tolstoys were able to make it inside only by using a special entrance. The crowd rushed to the train, and the wave of people carried Maklakov to the railway car with Tolstoy. Through the open window, Maklakov saw Tolstoy thrust his head forward, and, mumbling with an old man’s voice, with tears flowing down his pale cheeks, he thanked the people for their sympathy, which he said he “hadn’t expected.” He didn’t know what more to say, and, noticing Maklakov, turned to him with relief; no longer able to comfortably appear before the public, he was content to see a familiar face.

Countess Sofia Tolstoy, with a dedicatory inscription to Maklakov, July 2, 1896. © State Historical Museum, Moscow.

Maklakov closes the 1928 “Teaching and Life” speech with these words:

At Astapovo, a few months [after the departure from Moscow], he said to those nearest him, “You’ve come here for Lev alone, but in Russia there are millions.” He could talk that way and think that way. And the world loved him all the more that he thought that way. The world appreciated that Tolstoy, having received all the blessings that the world can offer, was not tempted by them. The world could not but be touched that, with access to all that, Tolstoy preferred a life according to God. And it was all the more striking that Tolstoy came to the precepts of Christ not because he was ordered by God but because he found them a sensible basis for human life. . . . To not consider Christ God, to not believe in life after death, to not believe in requital, and all the same to preach those precepts, to consider that joy consists for a human in renunciation of individual happiness, in life for the good of others, meant to reveal a faith in good and the goodness of man that no one in the world had ever had.

The world did not follow Tolstoy, and it was right. His teaching was not of this world. But listening to Tolstoy’s message, the world opened in itself those good feelings which the trivia of life had long since drowned; the world itself became better than it ordinarily was. Tolstoy did not flatter it, but stirred its conscience and lifted it to his level. And while Tolstoy lived, the world saw in him a living bearer of faith in goodness and in man. Thus the life of Tolstoy was so dear to the world that on November 7, [1910], when Tolstoy died, the world was no longer what it had been. Something in it died forever. But Russia, in which Tolstoy lived, and which he would not have traded away for anything, Russia, which he loved most of all—Russia, humble, poor and backward, which did not know what misfortunes lay before it, did not foresee that it would soon come to know by its own experience the whole depth of human vileness and cold-blooded indifference, Russia instinctively felt that on the day of his death it lost its protector.29

Did Maklakov’s association with Tolstoy affect his own behavior as a public figure? If you look for specific impacts, you will find few. One of Maklakov’s favorite words is the untranslatable gosudarstvennost, which has some overtones of “rule of law” but tends perhaps even more to connote the simple value of having a working state, standing athwart chaos. He often observed that even a bad state was generally better than no state at all; Tolstoy, of course, engaged in no such pragmatic comparisons. While Maklakov obviously did not like war, he was no pacifist: he believed there were circumstances where the consequences of refusing to fight were worse than those of fighting. But Maklakov’s reasoning was almost invariably pragmatic and consequentialist.

One issue escaped Maklakov’s general rejection of Tolstoy’s political positions—the death penalty. (Even here Maklakov’s position is qualified by pragmatism—he regarded it as essential in wartime.) Perhaps his most famous speech was his attack on a system of virtual kangaroo courts created by the tsar and Stolypin in the summer of 1906. The aim of this system, the so-called field courts martial, was to stamp out an ongoing wave of assassinations. Maklakov’s prime target was the procedures of the courts: their extreme speed, the absence of any right of appeal, and a virtual presumption of guilt once the defendant was charged. We’ll come to the speech in the discussion of Maklakov’s role in the Second Duma. For now, the interesting feature is that his argument against the death penalty takes a Tolstoyan form. Rather than marshaling policy arguments (the uncorrectability of errors, the questionable deterrent effects, the consequences for Russia’s reputation in Europe, etc.), he tells a story: Characterizing the procedure as “a legal rite of death,” he invites the listener to observe the scene when the death penalty is applied:

They lead a person, captured, disarmed and tied up, and tell him that in a few hours he will be killed. They allow his relatives to bid farewell to him—near and dear to them, young and healthy—who by the will of other humans will die. They lead him to the scaffold, like cattle to the slaughter, tie him to the spot where the coffin is ready, and in the presence of the doctor, procurator and priest, who have been blasphemously called to watch the business, they quietly and solemnly kill him. The horror of this legal assassination exceeds all the excesses of revolutionary terror.30

Of course Maklakov might have come to such a viewpoint, and to such a rhetoric, on his own. But the reliance entirely on description and the complete avoidance of policy arguments and consequences, smacks of Tolstoy.

Yet Tolstoy’s influence on Maklakov seems most powerful at a broader level—in Maklakov’s capacity to see alternative viewpoints, his practice of fairly discussing contrary claims even while advocating whatever approach he had come to regard as best. Earlier we saw his recognition of the contradictions between Tolstoy’s theories and his life. What could give a man more readiness to see the other side of an issue than to enjoy the friendship of a man whose life was a world of contradictions; to admire—indeed to worship and even love—a man whose mental processes and convictions were virtually the opposite of his own; and to recognize this man, whose political judgments must have seemed almost crazy, as a beacon for Russia and the world?

Of course the child who responded to his classmate’s proposition about the origin of the universe by asking where the red-hot sphere had come from was not likely to buy simplistic positions, to disregard the vulnerabilities of any contention. But Maklakov’s long relationship with Tolstoy seems likely to have fostered his sense of truth’s complexity.

Maklakov’s extensive memoirs never discuss his romantic life. The Moscow archives of his papers contain a record of his divorce from Evgenia Pavlovna Maklakova in 1899,31 but so far as I can tell have nothing else about the marriage. The archives also contain a good deal of correspondence of an “intimate character,”32 but I’ll address just two relationships of special interest (overlapping in time): with Lucy Bresser (whose stage name was Vera Tchaikovsky), a voluminous correspondent,33 and Alexandra Kollontai, a major political figure in her own right.34 Despite the silence of his memoirs on the subject, Maklakov seems to have been not at all secretive about his loves. Rosa Vinaver, wife of his Kadet colleague Maxim Vinaver, tells of a train trip from St. Petersburg to Paris, during which she conversed with him all the way until they were approaching Berlin. Maklakov said, “Here I must get out. I’m about to meet a very interesting lady.” On the platform appeared Kollontai, “as always graceful and elegant,” says Vinaver.35 Recall that Maklakov named a happy family life as “the crown” of Tolstoy’s enjoyment of worldly blessings; yet we really have no clue why he didn’t seriously seek out that blessing for himself.

The relationship with Lucy Bresser involved at least a momentary brush with marriage. It began with Maklakov’s providing legal representation in some dispute in which Bresser seems to have been involved as a relative of a party. Her first (preserved) letter to him starts as follows:

I am writing this not to the dear companion of a night’s journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow but rather to the unknown lawyer who sat with me in the Buffet of the Palais de Justice—whom I had the honor & intense satisfaction of thanking—of thanking for his efforts & success by a kiss.36

The breathless style continues for about four hundred pages over nearly a decade, with punctuation rarely taking any form other than a dash. Lucy was married to a Cyril Bresser, so any marriage to Maklakov would have required a divorce. Evidently Cyril wasn’t ready to agree to one, so “apparently we shall have to find someone to swear that we were together—the difficulty is to make Cyril sue me for divorce.”37 The social stigma involved is suggested by Lucy’s mother’s reaction: “My mother calls me a prostitute & that I ought to be shot—if only someone would do it.”38 Maklakov (as quoted back to him in her letters, our only source) responded rather captiously to the need to show guilt under English law: Lucy quotes his rhetorical question: “Qu’est ce qui empêche de devenir coupable?” and in English, “What’s easier than to become guilty?”39

More troubling, Maklakov seems to have reversed his position on marriage over the brief interval between June 8 and June 14, 1910. Bresser lays it out: “[O]n the 8th of June you reply to my question of divorce ‘Ai-je l’intention de t’épouser.’ Ah, il ne m’est plus difficile de le dire. Je le désire, je le veux de tout mon âme.” [“Do I intend to marry you. It’s no longer difficult to say. I want to, I want to with all my soul.”] Then “on the 14th your first letter of doubt arrived—what has happened between 8th & 14th?”40 If Maklakov ever offered a real answer, her letters don’t reflect it back. In a sense, the question is why he ever proclaimed his wish to marry her. He seems not to have been the marrying kind (or, more precisely, the remarrying kind), and her letters suggest a flightiness, even to the point of incoherence, that boded ill for the long term.

The relationship, though featuring many a rendezvous that filled Lucy with delight, was persistently troubled by her dependency. Her letters are filled with requests for money. He met many such requests, but not all—or not completely. We don’t know the exact words Maklakov used to resist the claims, but she clearly read them as suggesting that she was a kept woman. She saw the financial aid differently: his desire to be able to be with her at times that fitted his schedule necessarily impeded her freedom to pursue her stage career. She regarded his financial help as no more than compensation for that impediment.

Alexandra Kollontai, a Menshevik who evolved into a Bolshevik, could hardly have been more different. Like Maklakov, she was an impressive orator, stirring audiences with revolutionary fervor. Like Maklakov, she was named to diplomatic posts (in Norway, Mexico, and Sweden), holding the rank of ambassador after 1943; she had the advantage over Maklakov in that, unlike the Provisional Government, the government that appointed her remained in office. She was an articulate advocate of “free love,” or at least “comradely love,” and she lived in accord with her precepts. Her novel, Red Love, is a lightly concealed tract in favor of free love (or perhaps more precisely, against any feelings of sexual jealousy) and against what she saw as the triumph in the early Soviet state of commercial and managerial greed over pure communist ideals. The heroine’s husband is generally seen as modeled on the lover with whom she had the most intense and extended relationship, a worker named Pavel Dybenko; Red Love’s heroine is named Vasilisa—in homage to Vasily Maklakov?

The two seem to have gotten on very well politically. One letter reflects Kollontai’s reading of a series of Maklakov’s speeches in the Duma: “The first speech on the peasant question was very powerful, exact and successful. The later ones less satisfying.”41 Curiously, at the height of the Stalinist bloodletting in 1937, she wrote to a friend expressing a positively Maklakovian skepticism about Russia’s readiness for popular rule: “Historically, Russia, with her numberless uncultured, undisciplined masses, is not mature enough for democracy.”42

Like Maklakov, Kollontai wasn’t fully at home in her political party, though perhaps she was more vocal in her dissent. After the October Revolution she helped found a “Workers’ Opposition,” aimed at fighting bureaucratic encroachment on worker control in industry. Her (and others’) ardor in the project helped precipitate a Communist clampdown on intra-party expressions of dis-agreement: in 1921 the party adopted resolutions condemning the Workers’ Opposition and claiming the right to expel members for “factionalism.”43 As was true of Maklakov, she had a deep skepticism about her party’s leadership. In 1922 she told Ignazio Silone, an Italian Communist who later left the party, “If you should read in the papers that Lenin has had me arrested for stealing the Kremlin’s silverware, it will mean simply that I have not been in full agreement with him on some problem of agricultural or industrial policy.”44 Despite all this, she was the rare Old Bolshevik to die of natural causes (so far as appears), a little shy of her 80th birthday and just a year before Stalin’s death.

The two also shared a distaste for party partisanship—a distaste different from, but in keeping with their dislike of intra-party discipline. In 1914 a Bolshevik member of the Duma, Roman Malinovskii, was exposed as a double agent. The Bolsheviks were deeply embarrassed, and their Menshevik rivals piled on with criticism. Kollontai, then still a Menshevik, expressed her disgust to Maklakov. “The dirt we try to throw on Malinovskii above all makes us dirty.”45

Consistently with her views on romance, she rather playfully teases Maklakov at his suggestion that she might be jealous. “Have you forgotten that that intolerable, though perhaps interesting feeling, has completely atrophied in me?” Then she teases him further about rumors of the “intimate side” of Maklakov, rumors that there was some pretty Jewish girl that he had had to marry.46 The idea that someone moving in sophisticated Russian circles in the early twentieth century would “have” to marry someone seems a bit outlandish, but perhaps the rumor mills had generated such a story. Despite Kollontai’s amusement at the thought of her possibly being jealous, she sounds a touch possessive. She is plainly eager to see Maklakov whenever their paths might potentially cross, giving details as to how to reach her, and is openly disappointed when he goes through Paris and fails to get in touch with her at a time when he knows she is there. She says she does not want to lose him, and that she has not lost faith in him.47 The correspondence suggests there may be something simplistic in a purported total denial of jealousy: how is the line drawn between that and love’s natural eagerness to be with the loved one (and presumably not in a mob scene)? This may be why Red Love reads more like a tract than a novel.

Kollontai’s letters, especially one of them, devote a good deal of space to an analysis of their relationship. A letter sent in July 1914, on the eve of World War I, suggests she found in him an almost mesmerizing charm coupled with a frustrating remoteness:

When we parted yesterday, . . . it was as if a melody had been interrupted, not allowed to play to the end. And today yesterday does not disappear, thoughts about proof-correcting [she was a busy writer as well as a revolutionary] flee to yesterday, look for something, there’s not regret that the melody was interrupted, not sadness, there remains rather a smile, a small smile at us both. Isn’t it funny that we’re so similar? . . .

Our interest in each other is surprisingly intellectual! It isn’t boring—to the contrary! All the same—nothing in the heart trembles, is on fire. And it’s funny that each of us pushes himself to move to feelings. Together—we’re easy, not bored, but somehow relate as comrades. And we rebel against that. . . . You were far from any emotion, but when we went to the hotel you suddenly felt uneasiness; isn’t that natural? . . . And we both tried to find the right mood. But the question remains a question. Are conditions responsible for the fact that this interest always remains intellectual? . . . all the same, I’ve a right to have a really good relationship with you. I give you what is due and I know your value. Today I even sketched your silhouette in my notebooks. But, you know, there is something unclear, not individual about you—your relationships with women. To characterize you—one needs to find other strings to [the structure of] your soul. You aren’t one of those who would be characterized by your love life. And that’s especially curious in you, in whose life so many kinds of women have always been intertwined. But do you really distinguish between them? . . .

Do you ever hear the effect you have on a woman’s soul? You simply have no ear for that. In this we are not alike. I, unfortunately, hear very well what develops in my partner’s soul, and it horribly complicates relationships. But there is another mark that brings us together [she never seems to say what this is]; but you do not love that, her individuality, nor her love for you, but rather your own experience. You forget the name, face, the specialness of the woman, however fascinating she may have been, but you never forget if you yourself went through something sharp, special. You know this. But what must exasperate them, your future loved ones, is your absolute inability to reflect the image of the loved one. Especially for women who are not too gray, they much more than men love to have a mirror in the face of their partner, in which they can be loved. But you, among the very rarest varieties distinguish only “gender” and “species,” like a naturalist. Those poor women! A question interests me: how is it then that you captivate them?48

Kollontai’s questions, of course, remain unanswered, as do our own more prosaic or bourgeois questions about his failure to find—perhaps ever to seek—what he called the “crown” of worldly blessings, a happy family life.