Читать книгу A Letter from Frank - Stephen J. Colombo - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

One

Оглавление“Sweet”

Ein Kleiner Junge

A lone Sherman tank stood silently in the sun. The tall man in its turret, field glasses to his eyes, scanned the countryside, searching and listening. “Kill the engines,” Russ ordered the driver. He strained to hear. Far in the distance came the clatter and pop of weapons firing from the direction of Falaise. He ignored them, seeking the groan of a tank motor or the crack of its cannon. There was nothing.

He stared into the shade of a nearby grove of trees. The breeze brought the pungency of the decaying leaves blanketing the forest floor. The smell was sweet compared to the foul odours below; the unwashed bodies and hundreds of cigarettes smoked in that small space. For a week they had not more than an hour or two sleep each night as they hunted German soldiers escaping from the terror around Falaise. Now they hunted two of their own tanks. In the warm sun Russ relaxed, and with the scent of the forest in his nostrils, his eyes slid closed. That moment he dreamed he was a boy in the forest near his home.

Russ’s feet sounded like a drum on the path as he ran through the sun-flecked forest. From behind he heard the excited yells of boys chasing him. Volunteering to be their quarry, he’d run ahead while the pack shouted as they counted down. They yelled the final number, announcing the beginning of the chase from the base of an old rough-barked maple tree in an opening in the forest. If caught before making it back to the tree, the penalty was to be dragged to the river and thrown in.

Hearing their calls, a shiver ran down Russ’s spine. He imagined his pursuers not as sons of respectable families, but as German soldiers from the Great War chasing him behind enemy lines, branches in their hands serving as rifles tipped with razor-sharp bayonets. The boys’ voices grew louder as they spread out along the paths running like veins through the forest. Owl hoots and wolf howls were their signals to one another. Evading capture, Russ finally emerged into the clearing where the large maple stood. But just as he felt triumph surge through him, shouts came from behind.

“There he is!” they called, the thrill of capture and punishment in their minds. Other boys appeared, all of them sprinting to catch Russ before he reached the tree.

With a lunge, his hand touched the trunk, just as several pursuers dragged him to the ground. Rising to his feet, one of the boys, bigger than all the others, boldly claimed Russ was caught before touching the tree. The other boys gathered like a jury to listen to the learned arguments of these forest attorneys. Other than Russ, no one was sure what had actually happened, but the thought of throwing someone in the river appealed to them, and Russ knew he was losing the argument. Staring at the bigger boy, Russ said he’d reached the tree safely, and if they insisted on throwing him in the river, he would not go in alone. Everyone knew a challenge had been issued. This might be more interesting. All eyes turned to the bigger boy.

Before he could reply, to the disappointment of all, the high-pitched blast of a factory whistle sounded in the distance. No one waited to hear the bigger boy’s response as they rose as one to walk towards town. The whistle, heard throughout Owen Sound, signalled the end of their fathers’ workday.

The boys emerged from the forest along the western side of town. In the distance a large grain elevator stood on the edge of the harbour. The town was the fulcrum between eastern Canada’s cities and western Canada’s farms. The elevators were filled with wheat from the Prairies, brought by lake-going steamers from the western end of Lake Superior across the great inland lakes to Owen Sound. There it waited to be loaded onto rail cars for the final leg to eastern cities.

Owen Sound was once a small village of fisherman and farmers. But the coming of the railhead created a boom, and it grew wild, like many frontier towns. Strangers and saloons came looking to make cash quickly. Other industries followed; small factories, sawmills, and boat builders. The town was brought under control by those who built churches, elected a mayor, and supported a local constabulary. Among those men who wrestled Owen Sound into order was William Kennedy, who by the 1920s built his father’s business into a thriving metal foundry. It was Kennedy’s whistle the boys heard. As ten-year-old Russ walked towards home, his father Charles emerged from inside Kennedy’s walls, soot on his clothes and pipe clenched between his teeth.

Russ jerked awake from that blessed moment of unwanted sleep. Any slight distraction could all too easily get him and his crew killed. It was the throaty engine rumble and creaking tracks of an approaching tank that had woken him. In that disoriented instant he couldn’t tell from which direction the tank came. “Start the engines!” he bellowed below, cursing his moment of weakness. How long had he been out? As his heart raced, his mind cleared and he remembered they hadn’t seen a German Panzer in days, other than burned out hulks littering the countryside around Falaise. The tall outline of a Sherman tank churned into view, a cloud of dust billowing behind it. Relief turned to hope, and then to disappointment when Russ saw it was not one of the missing tanks, but one nicknamed Margorie. Standing in its turret was his friend, Jim Derij (“pronounced Derry,” as Jim tired of telling those who butchered his name).

Russ and Jim were assigned to the same unit a few months before D-Day, both newly qualified as lieutenants, each given four tanks as their first command. Together they guarded the Fourth Canadian Armoured Division’s headquarters — General George Kitching and his mobile communications centre. Besides being the most junior lieutenants in the divisional headquarters, they were also its only combat officers. And they were about the only two officers at headquarters not calling themselves British by descent. That may have had something to do with the bond they formed.

Jim directed his driver to bring Margorie alongside Russ’s vehicle. The lieutenants climbed down in the narrow space between the tanks, exposing themselves as little as possible, aware of the risk of German snipers. Talking tiredly, they found neither had encountered any sign of the missing tanks. Eighty tons of steel and ten men had simply vanished into the French countryside.

Owen Sound had a quiet caste system neatly segregating its society. There were those who were British and those who were not. Those it favoured seldom disregarded that system. The British — English, Anglo-Irish, or Scots — occupied the top rungs. Everyone else came below that. Near the lower end were those from southern Europe. This was the society Charles Colombo entered when he arrived in Owen Sound in 1905. It was a far cry from Baden, the largely German town he’d grown up in. Hearing German spoken on the streets of Baden and nearby Kitchener was common. But speaking German on the streets of Owen Sound would have been frowned on by some.

In Owen Sound, Charles’s last name identified him as a foreigner. Few knew the ethnicity of his name. Charles learned soon after arriving in Owen Sound to expect a cold response at best when he told someone his father spoke only Italian and his mother only German. It was hard to say which people considered less desirable: German, still stigmatized by the Great War, or Italian, a people viewed as unwanted and undesirable. Though Charles was born in Canada, being maligned for one’s “foreign” nationality was commonplace in Victorian towns. Despite the stigma attached to his name, Charles was made foreman of a crew of men with names like McDearmid, Sutton, and King. Their resentment was hardly surprising.

If Charles had wavered in the face of social standards, his son Russ would never have been born. Owen Sound’s respectable society would never have approved of Charles, the Italian boarding house resident, romancing his landlord’s visiting niece. But this is what happened when Blanche Cheney, a young American, visited her aunt in Owen Sound.

When Blanche returned to Genoa, Ohio, after her visit, she broke the news to her parents. She hoped they would respect her wish to marry Charles and move to Canada. She also had to break the news to the minister she was engaged to. Her parents reluctantly gave their blessing, allowing Blanche to marry the enigmatic Charles that summer. It was not often an Italian Catholic such as Charles married an English Protestant.

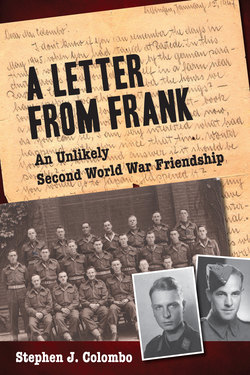

Charles and Blanche with Russ (lower left), Verdun, and Jack in 1916 in front of their home on 492–14th Street West, Owen Sound.

Together they prospered in Owen Sound, raising three boys in their sprawling house. They grew peonies and roses in their garden, and gathered eggs from the coop Charles built in the backyard. Russ was the third of their three boys, born on Valentine’s Day, 1916. Blanche nicknamed him “Sweet.” He had two older brothers. The first was born a year after Charles and Blanche married. The second arrived on Christmas Eve, 1914. When his second son was born, Charles patriotically flew a Canadian flag on his front porch and named the boy Verdun, after the French city that had stood almost alone against the Germans. At the time, the outlook for the Allies was terrible, and each day’s newspaper headlines were viewed with foreboding.

Charles did not join either of the volunteer regiments Owen Sound sent to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Men in war industries were told anyone could learn to carry a rifle, but they were needed to keep production moving at Kennedy’s, an important manufacturer of propellers for navy ships and shell casings for the army.

Kennedy’s boomed from war contracts during the Great War and continued to boom in the 1920s. Charles and Blanche and their small family likewise flourished. Their automobile was made possible by the thirty dollars a week Charles made for the fifty-five hours he worked. Each workday began at seven a.m. with a blast of Kennedy’s whistle and ended with another ten hours later. Kennedy’s was the hub of their lives.

The large machinery at Kennedy’s fascinated ten-year-old Russ. His father showed him how the wooden forms were like hollow eggs when packed with a shell made of wet sand and clay. Mold-making was an art complicated by the shrinkage of the metal as it cooled, requiring forms to be larger than the final size of the cast object. On the Sunday afternoon of his visit the large metal bucket hung on a hoist from the ceiling was still warm to touch. When the sand in a form dried, the bucket was manoeuvred overhead for pouring. If the sand mold was not dry enough, his father explained, there would be an explosion of high-pressure steam, and molten metal would fly into the air like an exploding volcano.

Charles watched Russ run to the far end of the foundry, where a massive bronze propeller stood. Russ ran his hand along the swan-like curve of the giant propeller’s edge. It had come out of a gigantic wooden form and was destined for a Great Lakes freighter being built in Collingwood. Before the form was cracked open, a crowd of factory workers gathered. A major flaw was costly, requiring the casting to be started over. Charles, accompanied by Mr. Kennedy, closely examined the expensive casting. The suspense lasted close to thirty minutes, and in the end Mr. Kennedy shook Charles’s hand. The final step was cleaning the layer of sand adhering to the casting’s surface. A high-pressure air hose blew the sand off the metal, filling the foundry with a fine dust.

Russ coughed as dirt thrown in the air by Jim’s tank settled in his throat. As the two lieutenants discussed where to take their search, a jeep came bouncing towards them. Russ recognized Major Campbell in the passenger’s seat, one hand steadying himself on the jeep’s dash while holding his helmet on with the other. Russ involuntarily looked at his uniform to see if anything was out of place.

When Major Clarence Campbell had taken command of the Headquarters Squadron, only weeks before D-Day, word quickly spread that he was the same Campbell who was a referee in the National Hockey League. His troops became familiar with the fiery temper he sometimes displayed as a referee. Opinions on Campbell were split between the career soldiers and some of the volunteers. Most career soldiers, like Jim, found Campbell tough but fair. But to some, like Russ, volunteers for the Canadian army who for four years had trained interminably while often living in miserable conditions, Campbell’s criticisms for minor lapses were harder to accept. Now that the Division was in Normandy, to the men, stressed by near constant combat and lack of sleep, an eruption of his temper was the last thing they needed.

Since reaching Normandy in late July 1944, the Fourth Division’s armoured regiments had been badly mauled by the Germans. Within the first week of arriving, their deadly 88-mm guns destroyed many Canadian tanks. As the division’s tank regiments were decimated, Russ and Jim increasingly found their tanks dispensed to the hottest parts of the battlefield. But the missing Headquarters tanks had vanished during what should have been a simple reconnaissance mission. Since then, the Major had pushed Jim and Russ to locate them, as if he held them responsible. It was another case of the Major causing Russ’s anger to roil just below the surface.

Russ’s fist slammed into the other boy’s cheek, snapping his head backward. At six feet, sixteen-year-old Russ was as tall as the nineteen-year-old. The older boy stumbled backwards and fell. Russ rained punches on him, his blue eyes cold as steel.

“I give up!” the boy said, blood running from his nose and an eye beginning to swell shut. Russ stopped punching and stood up.

Shortly before, the older boy had seen Russ making a beeline across the road towards him. Russ had already started a fight with two of the older boy’s friends. Both older boys were left bruised and bloodied. The first had not remembered why Russ was angry with him. The second boy knew why, and though at first he’d held his own, Russ’s willingness to be hit if it meant he could hurt someone more proved too much. Now Russ was on to the third and last.

The older boy retreated into a nearby park, apologizing as Russ swiftly covered the last few feet. Russ swung without hesitating, hitting the older boy squarely on the face. It was too late to apologize.

The older boy lay on the ground as Russ walked to a nearby drinking fountain. He took a long drink then wiped his mouth on his sleeve. He held his fist under the stream and washed blood from it. Taking a final look at the vanquished boy, he pushed his wavy brown hair out of his eyes and walked away without saying a word. Now they were even.

Three years earlier at this same drinking fountain, they’d caught Russ in the park. The three sixteen-year-olds thought it fun to push the thirteen-year-old around, laughing as he fought to get away. Dragging Russ to the fountain, they sprayed him with cold water, soaking his hair and clothes, and finally they spat on him, the yellow spittle stinking of chewing tobacco. They shouldn’t have laughed when Russ swore he would get even.

Major Clarence Campbell returned the salutes of his two lieutenants, joining them between the tanks. They reviewed where the missing tanks were last seen, what direction they were travelling in, and what areas had been searched.

The tanks had disappeared after escorting General Kitching to meet the Division’s senior officers at a small quarry near the village of Noney-en-Auge.[1] Even though the tank regiments had swept the area the evening before, Kitching had taken the Headquarter Squadron’s tanks for his protection. He was asked if the tanks could reconnoitre an area for a nearby British artillery unit. He let them go, one his command tank with its radio serving as a mobile command post. The cannon was a wooden replica, allowing room for the radio equipment the General needed to communicate across the battlefield. When the meeting ended, the tanks still had not returned. With no radio message from the command tank, Campbell, Colombo, and Derij knew the missing troopers were likely dead or had taken been prisoner.

A small group of men stood at the entrance to Kennedy’s foundry and stared at a handwritten sign on the door. It contained only two words in large block letters: “No Jobs.” It was there to stop the steady stream of men looking for work. What a change 1933 was compared to the boom years of the 1920s. Desperate men would do anything for a few hours of work and to get a foot in the door. “Need another man today?” they’d ask. “Sweep the floor for you? Can I run a letter across town?”

Since the start of the 1930s, orders had slowed to a crawl. The foundry was now surviving from month to month. Some of the men were showing signs of stress, the result of constant worry about their jobs. A few became reclusive and sullen, others were overly friendly and talkative. One imagined plots by coworkers to take his job or by management to lay him off. Charles knew his job was secure as long as orders trickled in.

The first incident happened so innocently, it passed Charles unnoticed. As the end of the workday approached, he prepared to run the gauntlet of those waiting outside. He stepped outside the foundry door at the end of his shift, lit his pipe, clamped it between his teeth, and began briskly walking home. This day, though, he found himself short of breath. He stopped walking but for just a moment felt he could not get enough air. He put the episode down to his age, though he was not yet fifty.

In coming weeks his shortness of breath grew worse. The idea emerged that his age was not the problem. When he could no longer ignore it, he visited his doctor, and when X-rays were taken and the diagnosis made, it wasn’t a complete surprise. Silicosis, the disease dreaded by miners, was not uncommon among men who worked in foundries. Charles had seen the effects in others. He even knew the cause was years of breathing silica dust. For decades, sand from the castings had settled in his lungs, silently inflaming the tender tissues. Its effects remained hidden until the damage became critical. It was so bad, his scarred lungs made it impossible to take in enough oxygen. The feeling was like being tortured by slow suffocation. His doctor described how the lack of oxygen was causing the blood vessels to constrict, and the resulting high blood pressure was straining his heart. The doctor was blunt — this would lead to a heart attack. The only question was when.

Charles grew thin, and soon his clothes hung on him like a scarecrow. His eyes sank into his gaunt face, and all but a few strands of his once wavy black hair disappeared. But a son can be the last person to see his father’s mortality, and Russ denied the reality of his father’s decline.

The scales finally fell from Russ’s eyes one day when he walked with his father to Kennedy’s. Charles halted at the corner, grasping Russ’s arm. “We have to stop.” As he stood there, waiting for the breathlessness to pass, it grew worse.

Putting his hand on his son’s shoulder for support, Charles said, “We have to go home. If I cross the road, I’m sure I’ll die.” The words were like a knife sliding between Russ’s ribs. After slowly making their way home, Russ helped his father onto the couch. He finally realized how ill his father was, seeing him gasp for air like a fish out of water, mouth agape and eyes silently pleading. Later, when he was alone, Russ cried quietly for his father and for himself.

Since his diagnosis, Charles planned for a future he knew he would not be part of. He brought Jack home from Niagara Falls, hiring him at Kennedy’s. Verdun had completed high school and was working. Charles told Russ he must quit high school and find a job. He was sixteen. Each paycheque the three boys earned was given to their father.

But in 1932, jobs were scarce and Russ was fortunate to find even manual labour, or pick and shovel work as he called it. One job was as a lumberjack, cutting trees for a local sawmill. The dense beech and maple wood was hard enough in summer, but in winter, the frozen wood turned hard as steel. Even on the coldest days, standing thigh deep in wet snow, Russ was soaked with sweat from pulling the bowsaw or chopping wood with his axe. His arms and shoulders grew, and inches of muscle were added to his lean six-foot frame.

Saturday morning of August 4, 1934, was cool, and Charles looked forward to a shift that lasted only until noon. Charles and Jack began work promptly at seven. Although foreman, Charles enjoyed working with the sand, clay, and water, bringing it to the proper consistency for the forms. As he mixed the sand and water, he felt the familiar shortness of breath, and a throbbing in his left arm. He ignored both, as he always did. But this time it grew worse. He fell to his knees and was unconscious before his head reached the foundry floor. He died there on the cold floor at Kennedy’s.

Charles died during the depths of the Depression. Soon after, Verdun departed for the United States. Jack kept his job at Kennedy’s, and Russ, then eighteen, worked at any job he could find, usually hard physical work. Although close to one in five in Owen Sound were on public relief, they earned enough to avoid it. Despite the Depression, the death of his father, and the departure of Verdun, Russ’s life slowly regained a sense of normalcy.

Russ directed his tank’s driver onto a narrow lane leading into a large patch of forest. The lane was well-hidden by a fold in the perimeter of the trees, which had gone unnoticed when they passed this way the day before. Only by chance did Russ notice the lane leading into the forest this day. The Sherman moved forward slowly. From his position in the turret, Russ was first to see the missing tanks. Ordering his driver to stop, he surveyed the scene. There was no movement or sound.

“I’m going to have a look,” Russ told his crew. He climbed out, taking his pistol from its holster. Walking towards the two tanks, he felt exposed. They were lined up on the narrow path, some forty yards from where Russ had stopped his own tank. Reaching the first of the tanks, he climbed up onto its deck. It was the General’s command tank, its wooden cannon easily identifiable. Peering through the open hatch, Russ saw the radio torn to pieces — and none of the crew.

Jumping down, he walked to the other tank. He saw a hole on the hull where a shell had exploded. He climbed up and peering inside smelled the sulphurous odour of the explosion. He imagined the panic when the tank was rocked by the explosion, filling the turret with smoke. They were fortunate the explosion had not ignited the ammunition. He understood the indecision the crew must have felt, knowing if they bailed out they would likely be shot down, but waiting inside they might be hit at any second by another shell.

Climbing down, Russ examined the three-inch hole in the hull. He traced a path away from the tank, in the direction of some bushes lining the laneway. Walking behind the bushes, he found a discarded Panzerfaust launch tube, a hand-held anti-tank weapon.

Russ pieced together what must have happened. The tanks were ambushed by a band of Germans attempting to escape the area. The joining of the Canadian and American armies near Falaise had completed the encirclement of the German Seventh Army. The Germans were desperate to escape north of the Seine, fighting through the thin cordon of Canadian troops spread out across the countryside. Despite closing the Falaise pocket, it was a leaky trap, and small groups of Germans continued to filter through the Canadian lines. The Germans hid during the day and moved at night. When the Canadian tanks entered the forest, they’d unknowingly disturbed a hornet’s nest.

The concealed Germans would have heard the approaching tanks, but seeing no infantry, they would have known it was safe to let them approach. When the trap was sprung, the lead tank was fired on from close range with the Panzerfaust. With the first tank disabled, the Canadian troopers would have pulled their hatches closed, making themselves virtually blind. Then the Germans could easily approach. They must have climbed onto the tanks and told the trapped Canadians to give themselves up or face the consequences.

The Germans had done their best to disable the captured tanks. They destroyed the breech of the tank’s cannon and shot up the command tank’s radio equipment. The only reason they hadn’t siphoned off gasoline and poured it inside the crew compartment to set the tanks alight was the attention the smoke and explosions would have brought.

There was no sign of the ten men who had been in the tanks. The troopers must have been taken prisoner, but by no means were they safe. Forced to accompany their German captors, the Canadians would be subject to attack from their own troops. But with the Germans desperate to flee north, dragging prisoners along would be difficult and a threat to the their escape. It was also no secret that members of the 12th SS Division had executed Canadian prisoners at nearby Ardenne Abbey. Remnants of that infamous division continued to be the nemesis of Canadian troops in the fighting around Falaise.

Russ returned to Headquarters and reported the discovery. Several days later one of the captured troopers turned up. He was a British artillery officer who confirmed what Russ had pieced together. He also told how he had escaped and reported the troopers were all alive and without serious injury. They were taken north by their German captors and were surely on their way to Germany and a POW camp.

During the 1930s, economic hardship forced thousands of Canadian teenagers to grow up quickly, taking on the responsibilities of adults. In 1938, Russ was twenty-two and the Depression was all he had known as an adult. He already had spent six years supporting his mother by working demanding jobs for low wages. It was pick-and-shovel work and bush jobs, with no end in sight. But it was hard to ignore concerns about a looming war in Europe, trumpeted in newspaper headlines and on radio. The world was split in two camps, the democracies led by Great Britain, the United States, and France, and the dictatorships of Fascist Germany, Italy, and Spain, and Communist Soviet Union.

Every day newspapers reported the threat posed by Germany to democratic nations. The focus shifted from trouble spot to trouble spot in Europe, fanned by the threat of Nazi aggression, from the Ruhr to Austria, the Sudetenland, Danzig, and Czechoslovakia. Since taking absolute power, the Nazis had shown their willingness to treat their own citizens with violence. Canadians already were reading about concentration camps, where brutal treatment was the norm.

While other nations stepped up the production of armaments, Canadian politicians said they would support Britain in the event of war, but did little to increase the size of the armed forces or to equip them. When 1938 came to a close, Canadians had a sense of foreboding that war was inevitable. If war came, it would require young men like Russ to put their lives on hold and shoulder even greater responsibilities than they had faced during almost a decade of the Depression.