Читать книгу A Letter from Frank - Stephen J. Colombo - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Two

ОглавлениеFremd im eigenen Land

A Stranger in His Own Land

Frank’s pulse raced with the roar of the engine. He was the lone passenger on the small Junkers W34, skittering across the runway in northern Finland as the pilot swung the tail around, coming to a stop facing down the long asphalt strip. The pilot pushed the speed control lever forward, causing the small craft to shake in anticipation. Suddenly, it jumped forward as he let go of the brakes, and Frank grabbed the edge of his seat, his hands slippery with sweat. The accelerating aircraft bounced along the runway, and as the nose lifted, the pilot pulled back on the control column.

The pilot turned to look at the blond paratrooper, whose face was pressed against the window as the plane rose into the air. He looked barely more than sixteen, like a boy dressed in a soldier’s uniform, though his identity card said he was twenty. The pilot chuckled, remembering when he had checked the young man’s orders against his identity card. Both said he was Franz Sikora, but when the pilot called the boy Franz, he was told, with a hint of defiance, that despite what his papers said he was Frank. Franz was his father’s name.

The weather in Freistadt,[1] Czechoslovakia, was cold and rainy and, as always in such weather, Franz Sikora’s legs ached. He limped slightly, walking slowly to the court office. His head also ached from the celebration of the previous evening. His friends had joined him, raising glass after glass to celebrate the birth of Franz’s first child, a son. The men he celebrated with, all in their early thirties, were veterans of the Great War, members of the same regiment from their town. The regiment was raised in 1914 in the Teschen region, part of Austria-Hungary. Glasses were raised to toast Franz’s son and his wife Josefina. Though his drinking this night was an exception for Franz, the celebration continued late into the evening. As usual when the old comrades met, the conversation turned to the former commander of their regiment, to friends who had not returned from the war, and to those like Franz who had been badly wounded.

When his friends asked what the boy would be named, Franz paused for a second then told them his son would also be named Franz. The friends stood up, held their glasses before them, and in unison said, “To Franz.” They refilled their glasses but then sat silently. They thought of happier times for Germans like themselves.

Franz looked in the mirror at his legs as he dressed for work the next morning. They were thin and very white, like two fragile sticks. He ran his hands over the pockmarked skin, puckered and purple where the machine gun bullets had struck him as he had gone over the top of the trench in an attack on Allied lines. Finished dressing, he put his son’s birth registration in the breast pocket of his jacket. As he walked the narrow cobbled street to the court building where he worked, he felt nervously for the papers, anticipating the reaction of the Czech official when he saw the name printed on the forms.

Naming first-born sons after the emperor was a tradition all Germans in Teschen had once followed. But in 1924, when Franz’s son was born, Austria-Hungary no longer existed. Teschen had been made part of a new country, Czechoslovakia, ruled by the Czechs from Prague. And the emperor was long dead. Franz-Josef died in 1916, when the Great War still had years to run. It was just as well he had died when he did, Franz thought, since it would have tormented the great old man to see the country he’d ruled for more than fifty years split up. Naming his son Franz was a tribute to a time when Austria-Hungary still existed and Teschen was ruled by Germans, as the Czech in charge of the court office would be well aware.

Franz’s family was German not because they lived in the country of that name. They were German by heritage, descendants of the migration in which, centuries earlier, their forbears moved east across central Europe. Just as there were large differences among people in different regions within the borders of Germany itself, Germans living in Teschen had their own distinctive culture. The region, with its unique dialect and traditions, had a reputation for peaceful coexistence, with Germans, Poles, Jews, Czechs, and Slovaks living in reasonable harmony. That changed after the Great War.

The pilot pushed the control column forward, causing the plane to plunge earthward. He turned to see his passenger’s reaction. He was not disappointed as he saw Frank’s eyes the size of saucers and his arm braced against the fuselage.

When readying the plane for takeoff, the pilot had asked Frank how long he had been a paratrooper. Frank had volunteered for the Luftwaffe when he was seventeen and was starting his third year as a Fallschirmjäger. He told the pilot he too had wanted to fly but had been turned down by the doctors. He was excited to finally have the chance to go up in an airplane. The pilot remarked at the irony of a member of the Luftwaffe never having flown, and decided to give the young man a first flight he would never forget.

As the plane hurtled earthwards, it gathered speed, the air roaring over the wings causing everything to vibrate uncontrollably. Watching the earth, Frank saw a farmhouse rapidly growing in size. Just as he was sure they would crash, he felt a tremendous pressure on his body, like a giant hand pushing him down into his seat. As the pilot pulled the plane out of its steep dive, Frank felt he could breathe again. But the relief was short-lived. The plane turned on its right side, wings perpendicular to the ground, pressing Frank against the fuselage. From the cockpit came the sound of laughter.

Franz was furious with the Czech in charge of the court office. The man had examined the birth registration form, written a short note in the margin, and filed the document away. The man had not had the decency to say anything; he’d acted as though the name Franz meant nothing. It was an insult to the old emperor’s memory.

Franz had to let all the arguments he had prepared slowly dissipate without being spoken. His longing for the old days was painful. The Sikoras had once been among the town’s large landowners, part of the local ruling elite. The Sikora farms had produced food for market and provided employment for others. Their horses were so prized that the best were sold to the Habsburg monarchy.

But after the Great War, the Sikora farms had been taken from them by the new Czech government. Like other large landowners, most of them German, their family farms were split into small parcels and given to landless Czech peasant farmers. With the loss of their land followed the loss of the status and prestige it had brought them. The payment Franz and Josephina received was a fraction of what the land was worth. Franz had nothing against the Czech peasant farmers, but he believed the Czech government and the Allied powers lacked sympathy for Germans. During the chaos enveloping Central Europe after the Great War, three million Germans from Austria-Hungary and Germany became minorities in lands annexed and awarded to Czechoslovakia, Poland, or France. The Allied powers decided to slice off parts of Germany and to dismember Austria-Hungary. The new Czechoslovakia contained regions with large German minorities.

The changes in Teschen affected Germans more than any other ethnic group. In the time of the emperor, the Habsburg policies supported cultural and linguistic diversity and a degree of cultural autonomy. An uneasy peace reigned in the country. For the most part, the Germans of Teschen were landowners and took care of the government and administration, while the Czechs were active in business. The Poles mostly owned smaller farms and the Slovaks were often labourers and peasant farmers, many tending to pastures in the nearby Beskydy Mountains. In this rich cultural mosaic, a Jewish population also co-existed, its membership in the community and religious rights respected. Small communities of Romani wandered the countryside in their horse-drawn wagons, itinerant labourers who came seeking work. The different ethnic communities in Teschen continued living tolerantly after the Great War. But the loss of prestige among the Germans following the creation of Czechoslovakia had at a deeper level upset this peaceful co-existence among the region’s social classes and ethnic groups. Freistadt was on the surface still a quiet town, but the German population struggled to adapt to the new reality, a struggle the Sikoras exemplified. In this town of about five thousand people, predominantly German, many had difficulty accepting the loss of wealth and social position.

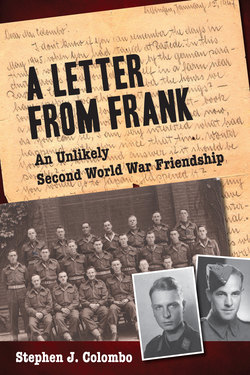

The town square in Friestadt (now part of the city of Karviná, Czech Republic).

Reproduced with the permission of photographer Lumír Částka (www.loomeer.cz).

Frank was oblivious of the upheaval his family was going through. His boyhood was an idyllic time. With other boys from different ethnic groups, he played in Freistadt’s cobblestone roads, running down the narrow streets lined with medieval buildings, many of them more than seven hundred years old. In the town’s Central Square stood a tall clock tower, a reminder of a time centuries earlier when it was a bulwark against invaders. Farmers from the surrounding countryside came to Freistadt’s market to sell homemade cheese, curds, eggs, and poultry. In summer, the farmers brought berries to market and in the fall wild mushrooms, picked by women from the forests carpeting the Beskydy Mountains. Poachers from nearby Poland arrived in Freistadt to sell rabbits and venison from the forests to the north.

The rolling countryside surrounding Freistadt was made up of fertile farms and forests. The lush forests were playgrounds for children of all backgrounds. Frank attended a German school, and his fellow students included the Jewish children of Freistadt. Life was not a Garden of Eden, but it certainly seemed it to Frank.

The cold mountain streams cascading through the forest were full of fish. Trout and crayfish brought high prices in the market. But the rivers were protected from fishing, preventing city boys from fishing outside of town without a licence. Luckily for Frank, the local game warden was a family friend who finally relented and issued him a fishing licence. It was a prize to have one, although it only permitted Frank to catch minnows and chub. His fishing equipment was a simple hazel branch, a few metres[2] of ordinary string, and a hook. His fishing license didn’t even allow him to use worms as bait. Frank spent most spare time in the forests, walking to favourite fishing spots with his homemade rod over his shoulder. He would return hours later, usually without any fish, but having spent time in nature doing what he most enjoyed.

While Freistadt seemed a near-perfect setting to grow up in, his parents came to realize there was little future for them there. With their lands gone and the small remuneration they’d received used up, the small family struggled. The court office was small and his father’s paycheque never seemed adequate. Franz found himself passed over for advancement in favour of Czechs who came from elsewhere. With the family grown to include a daughter, Eva, Frank’s parents decided to move to the larger city of Ostrau, a few dozen kilometres west.

Their parents told Frank, who was eleven, and Eva, seven, that life would be better in Ostrau. Franz would stand a better chance of obtaining a promotion. To children, moving to a new city meant making new friends, and on arriving Frank immediately noticed a glaring difference. In Freistadt, everyone mixed together, regardless of their background. In Ostrau, German and Czech children tended to keep to their own groups, each having their own schools, praying in their own churches, and frequenting shops run by their own people.

Ostrau’s court office, where Franz worked, used German or Czech, depending on the language of the legal participants, as was the case in Freistadt. This was emblematic of the thorny issue the Czechs faced, between granting more autonomy to Germans or trying to draw them into an active role in Czechoslovakia’s government. Allowing greater freedom in the country’s German regions, the Czechs worried, might eventually move Germans there to seek union with Germany.

In the early 1930s, many German Czechs were thrilled when a party came to power in Germany whose policies included the return of territory taken away after the Great War. The National Socialists took power in the German Reichstag through political opportunism, violence, and duplicity. By 1932, their leader had become the chancellor of Germany. He was an Austrian who had fought in the Great War and who, until the mid-1920s, had been a minor right-wing political figure. His name was Adolf Hitler.

While jailed in the 1920s, Hitler wrote a book describing his views on the causes of Germany’s problems. He used a visible minority as the principle scapegoat for the loss of the Great War and the country’s economic problems. The book was Mein Kampf, and the group he targeted was the Jews.

By March 1933, Hitler had consolidated political power in Germany, eliminated his major adversaries, and declared himself Führer. Nazi slogans proclaimed, “Hitler is Germany, Germany is Hitler.” By July, the Nazi party became the only political body allowed by law, and Hitler took absolute power.

Frank was not yet a teenager in 1935, when his family arrived in Ostrau. In Czechoslovakia, he was not exposed to the Nazi propaganda taught to schoolchildren in Germany. But adult Germans in Czechoslovakia were well aware of the Nazis and their doctrines. There was even a branch of the party in German sections of Czechoslovakia. Despite Nazi violence against their adversaries, and their persecution of Jews and Communists, for some their support of autonomy for Sudeten Germans made them an appealing political option.

As the 1930s went on, the German government flouted clause after clause of the Treaty of Versailles, which had set restrictions on defeated Germany after the Great War. In 1935, the government implemented conscription into the armed forces. In 1936, the demilitarized Rhineland was occupied by German troops, and in March, 1938, they unified Germany and Austria in the “Anschluss,” or “joining up.” The Anschluss was part political union, part incorporation, and entirely forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles. However, the Allied powers’ response was nothing more than disapproving public statements. German newspapers described cheering crowds greeting troops entering Austria. In Vienna, a quarter of a million Austrians gathered to hear Hitler speak from Emperor Franz-Josef’s Imperial Palace. Meanwhile, Jews, Communists, and Socialists were fleeing the country to escape persecution and imprisonment.

The Anschluss was watched enthusiastically by Sudeten Germans intent on gaining autonomy from the Czechs. Before the end of March, Hitler met the leader of the Sudeten German Party, Konrad Heinlein. Shortly after, Heinlein demanded the Czechs allow complete autonomy of the Sudetenland, and Hitler declared the urgent need to solve the “Czechoslovak problem.” Through the summer of 1938, tensions ran high, with the threat of war looming.

Some Czechs reacted to the threat of war from Germany by harassing Germans in Ostrau. Fourteen-year-old Frank heard about and witnessed the harassment. The names and addresses of leaders of the German community were collected by Czech authorities. Some Germans were forced from their houses and segregated in tenements. Czech police receiving calls for help from someone speaking German or with a German accent sometimes ignored the call. Army barricades were erected across streets, the men manning them asking those attempting to pass to use the Czech language, since most Germans could not pronounce certain Czech words without an accent. Frank’s parents were concerned for the family’s safety and looked for a way to keep Frank and Eva safe.

The plane twisted like a corkscrew as it slowly spiralled and plunged once again towards the ground. Straightening out at treetop level, it shot over a farmer’s field. Cows began running at the plane’s loud, sudden appearance. It dipped, passing just over their heads. In the cockpit, the pilot whooped like a cowboy at a rodeo, shouting back to Frank that the farmer would be surprised when his cows gave him sour milk the next day.

At the southern coast of Finland, he brought the plane to a normal cruising altitude and settled in for strictly routine flying. After landing at an airfield in northern Germany, the pilot disembarked and waited for Frank. When the boy emerged a moment later, the pilot asked his young passenger if he was still sorry he hadn’t been able to become a pilot.

Frank answered, “Of course, more than ever.”

The pilot smiled and vigorously shook the younger man’s hand. But when Frank grimaced, the pilot noticed the wound ribbon on Frank’s uniform.

The pilot apologized, telling Frank he hadn’t known he was injured, and hoped the in-air antics hadn’t hurt him. Frank replied that he shouldn’t worry. He wouldn’t have missed flying for anything, though it did feel good to be standing on solid ground.

Many Sudeten Germans felt Germany’s newfound strength was a great thing. Finally, they hoped, some of the wrongs done to them by the Allies after the Great War would be righted and their lot would improve. In September, 1938, Hitler issued the Czech government a series of ultimatums. First he threatened war unless Sudeten Germans were given autonomy. When this was agreed to, Hitler demanded the Sudetenland be put under German control. This too was granted. Finally, he threatened to invade unless German troops were allowed there. At the brink of war, the leaders of Britain and France met face-to-face with Hitler in Munich. In the end, Germany’s occupation of the Sudetenland was accepted, exchanged for a promise of peace. The outcome of the Munich meetings was presented as a fait accompli to Czechoslovakia. Most Sudeten Germans were glad to no longer be part of Czechoslovakia. But not all in the Sudetenland felt that way. For Jews and Communists, the Nazi takeover was cause for fear, and many fled in response, as had been happening in Germany and Austria almost from the moment the Nazis took power.

On the first day of the occupation, Frank and his friends rode their bikes, looking for German soldiers. They found them just outside of town, on the other side of the Oder River. They waved to the German tanks across the river, and the soldiers waved back. That night at dinner Frank talked excitedly to his family about the soldiers and tanks.

Frank’s parents were shocked to hear that the Germans had stopped short of Ostrau, and only then did they discover, to their horror, that the border Germany had negotiated did not include them. They were more concerned than ever that the Czechs would turn against Germans remaining in their territory. As if on cue, Franz was threatened with the loss of his job unless he moved Frank from his German primary school to a Czech one. It was only Frank’s mother’s refusal that stopped it. He wrote the Gymnasium entrance examination, which he passed allowing him to enter the German equivalent of high school.

There was scarcely a pause in the fast-moving events involving Germans in Europe. In Paris, two months after the occupation of the Sudetenland, a young Pole shot and killed a German diplomat in the German embassy. The assassin was distraught at the inhumane treatment of his family and other Polish Jews. His parents were expelled from Germany, where they had moved to work, but Poland refused to take them back. With neither country willing to take them, the refugees were trapped in a no-man’s land between the border posts. The diplomat’s death in Paris was followed by two nights of violence against Jews across Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland, which became known as Kristallnacht. German newspapers reported it as a popular response to the murder of the German diplomat.[3] In the violence, Jewish businesses were vandalized and synagogues destroyed. Thousands of Jews, even though they were the victims, were arrested and sent to concentration camps. The violence extended into some parts of Czechoslovakia where large numbers of Germans lived.

Fearing a backlash against Germans in Czechoslovakia for the loss of the Sudetenland, Frank’s parents decided their only recourse was to leave the country. They would move yet further west, into the area under German control. Their focus settled on the city of Leitmeritz, where Frank’s father interviewed for a job as court clerk. Returning from the interview, he told his family it would be perfect, a warm climate, fruit trees lining the river running through the city, and a high school for Frank. A mile south of the city sat the garrison town of Theresienstadt, used in 1939 as an army base for several thousand soldiers.[4] They would be safe from the violence that threatened Germans in Czechoslovakia.

The Sikoras’ relocation passed without fanfare. Frank and his sister said goodbye to their friends while their parents loaded their possessions. Frank felt no sadness at leaving Czechoslovakia. Instead, he was excited by the adventure of moving to a new city. His parents were relieved. Living in an area under German control, uncertain days would at last be behind them. Their relief was to be short-lived. Before the year was over, Hitler would push Europe into a new world war, and their son would be drawn into it.

The train for Leitmeritz left Czechoslovakia for the Sudetenland without having to pass through a border crossing. There were no Czech border guards restricting what they could take with them, and no German guards to inspect their papers. Their personal documents were the most important things they had brought with them. Those papers would be needed to prove they were pure Germans, their blood not mixed with that of Poles, Slovaks, and especially to the German authorities, not Jews. As Frank sat with his sister Eva and his parents on the train, he had no idea how worried his father was that someone might look closely into the family’s past.