Читать книгу A Letter from Frank - Stephen J. Colombo - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Three

ОглавлениеHometown Heroes

Helden der eigenen Stadt

In the early Sunday morning hours, people in Owen Sound emerged in ones and twos from house after house. They walked almost trancelike along the tree-lined streets, drawn towards the downtown. It had been a hot night, the kind where you lay awake in bed, the sheets sticking to your sweat-soaked back. But many found sleep elusive, not because of the heat, but because of worry. A war ultimatum had been issued. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain warned Hitler to withdraw German forces from Poland, or Great Britain would declare war. Canadians were told by Canada’s Prime Minister Mackenzie King that they would join Britain in such a war.

By dawn a small crowd stood outside the office of Owen Sound’s Sun Times newspaper. Seeing movement through the plate glass window, the crowd pushed forward. Inside, a group of newspaper workers read from a sheet of teletype. When they were done, a clerk approached the storefront and placed the teletype in the window. It was six a.m.[1]

“What does it say?” someone near the back of the crowd yelled.

A man at the window quickly read the bulletin and called out, “It’s war!”

Another man began reading the message aloud. “In a radio broadcast made today,” he told the hushed crowd, “Prime Minister Chamberlain announced that this morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German government a final note, stating that unless we heard from them by eleven o’clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you that no such undertaking has been received and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.”

The news spread quickly through the city. There was a sense something awful was coming that would test the country’s courage and resolve. In churches across Owen Sound that Sunday, September 3, 1939, ministers led their parishioners in prayer, asking for “God’s protection and support in the coming war.” When Blanche walked home from church, she thought nervously about the war and her sons. Jack, twenty-nine, was working full-time at Kennedy’s. She was certain Kennedy’s would be an important war manufacturer, as it had been when Charles worked there during the Great War. Jack, she felt, would follow in his father’s footsteps and contribute to the war effort where he was. Verdun had been in Philadelphia for five years, and had recently married. Verdun would not return to Canada, but even had he wanted to enlist, his bouts of severe asthma would have prevented it.

She felt less sure about Russ. He was twenty-four with a rebellious streak and had never found steady work, taking labourer’s jobs seldom lasting more than a few months. He was also her only son born in Canada. Now, more than ever, she regretted not travelling back to her parents’ home in Ohio for his birth. If he was American, he might be less likely to join the Canadian army.

While Blanche and other Canadian mothers worried their sons would enlist, Canadian politicians were worrying like adolescents on the verge of leaving home — wanting to show their independence but craving parental approval at the same time. Or so it seemed when Canada’s prime minister thought he would make a point by waiting seven days after Great Britain’s declaration of war before convening a special session of Parliament to declare Canada was at war with Germany. It was only a slight change from 1914, when Canada was committed to the Great War not by its own parliament, but by Britain’s declaration of war. Canada’s official announcement in 1939 was made in a short news bulletin read over CBC radio, but everyone knew it was a formality. And like many adolescents leaving home, Canada overestimated its readiness, since her permanent armed forces were woefully small and poorly equipped.

Some blamed Chamberlain for the war almost as much as they did Hitler. They felt that war might have been avoided if he had taken a hard stand earlier. Since 1936, Hitler had aggressively ignored the Treaty of Versailles. He had moved the German army into the Rhineland, rearmed Germany, and in the space of six months in 1938 had annexed Austria and taken the Sudetenland. In March, 1939, Germany had threatened to invade what remained of Czechoslovakia (to protect Germans living there, Hitler had claimed). In a misguided attempt to negotiate, the Czech president travelled to Berlin in search of a compromise.

Instead of negotiations, he was threatened with invasion. Prague would be destroyed by bombing if Germany was “forced” to take military action, and the Czech president would be responsible for the deaths of thousands of his countrymen. Without Britain and France to defend them, the Czechs had no hope of changing the outcome militarily. The elderly president chose to save his people from attack by agreeing with Hitler’s demand to create a German “protectorate” over what remained of Czechoslovakia. On March 15, 1939, the German army entered Czechoslovakia, and the country ceased to exist. The past year’s attempts at negotiated settlements with Germany by Britain and France were now seen as a wasted appeasement of an aggressive dictator. The invasion of Poland was the line they had drawn in the sand, and Hitler had crossed it.

The war came almost a decade into the Great Depression. Many Canadian men had seen little steady work through the 1930s, and to some, the war provided cause for optimism. Enlistment at least offered a steady paycheque, and for those opting for overseas service, an opportunity to see the world. Most also believed enlistment would protect Canadian values and way of life from fascism. However, at the outbreak of war, the Canadian army consisted of only 3,000 full-time soldiers.[2] Years of cutbacks to military budgets had left the armed forces short even of boots, socks, and blankets, and weapons were scarcer yet, causing enlistment to be phased in slowly.[3] Owen Sound’s local regiment, the Grey and Simcoe Foresters, was among those forced to wait to begin recruitment.

With war trumpeted in daily newspaper headlines across Canada in the summer of 1939, Russ found part-time work with the Canadian National Railway doing summer maintenance on the rail lines. When he could, he also played for the city’s new senior lacrosse team. He’d been invited to tryout by his childhood friend, Jack MacLeod. The team sweater he gave Russ had “Georgians” (for nearby Georgian Bay) emblazoned across the chest. The team manager was Jack’s father, Jim, and it was he that had introduced many Owen Sound boys to the sport, bringing lacrosse sticks home from a work trip and selling them to neighbourhood boys for fifty cents. Russ was one of those who had shown up with the money and, along with other boys, spent hours throwing a ball high in the air and jostling one another to catch it before it fell to earth. As skills improved, impromptu games took place.

The 1939 season was the Georgians’ first, and at the end it was considered successful. They’d finished behind only the strong Orangeville team. Russ was a dependable defenseman, and Jim MacLeod asked him to return the following year. Players drifted apart, and the lacrosse sweater Jack had loaned Russ was packed away for the winter.

His summer job on the railway ended not long after the declaration of war. Needing work for the winter, Russ decided to head to northern Ontario. In past winters he had worked for an Owen Sound sawmill owned by the American timber baron J.J. McFadden. But it had closed, and two of its managers had moved to work at McFadden’s new lumber mill in Blind River. As many as five lumber camps were needed to feed logs to the Blind River sawmill, and experienced men were sought. When word went out in Owen Sound that McFadden needed men up north, Russ applied and was told to report.

When Russ reached Blind River, he arranged for most of his forty-five dollar monthly paycheque to be sent to Blanche. From the $1.50 per day he earned, McFadden deducted the cost of food and purchases from the camp’s company store. Russ was driven north from Blind River to a camp deep in the northern wilderness.

He entered a spartan existence. The men were housed in large log bunkhouses. Beds were constructed from rough-sawn lumber, each man taking straw from the barn where the horses were kept and piling it on planks inside the wooden bed frame. There was no running water for washing, only metal bowls that could be filled with water heated on the wood stove. Food was the same every day: bread, beans, and fatback. Fatback was nothing more than pork fat. If lucky, you found a thin seam of meat running through it. With the bunkhouse closed up in winter, lit by oily kerosene lamps, no showers for the men, and a steady diet of beans, the air inside smelled like spoiled cheese.

Work began in the dark hours before sunrise, the temperature during winter often -30 degrees Fahrenheit or colder. After breakfast, the men piled onto a horse-drawn logging sleigh, coats buttoned with collars raised, scarves wrapped around their faces, and hats pulled down over their ears. To stay warm, Russ pulled on as many layers of clothing as he could, including the Georgians lacrosse sweater.

Russ, most likely at a McFadden lumber camp near Owen Sound.

The ride to the work site could be wild on the ice roads, kept slippery by water sprinkled from large horse-drawn tanks. Younger boys, nicknamed “chickadees,” walked the roads, scraping horse droppings from the ice so sleigh runners would skate smoothly along the ice roads. Traversing hills could be treacherous. With a full load, the horses took running starts to pull loads up the sides of slippery hills. Reaching the crest, the sleigh would perch for an instant before suddenly starting downwards. Sand, hay, or brush placed on the lee side of hills was meant to slow the descent, but if there was not enough sand or the hill was steep, the sleigh would hurtle downhill with the men hanging on white-knuckled, the horses galloping for their lives to avoid being crushed.

The men were lucky if there were packed trails from the road where they unloaded to their allotted sections of land. If not, they might have to wade through waist-deep snow. The lumberjacks worked near enough to one another to hear the sounds of saws and axes and the crash of trees hitting the ground. It provided each man a measure of his progress to hear those working nearby.

Most of the rough-barked white pine trees were two to three feet in diameter, a few monsters as much as four feet across. After a tree was felled and cut into lengths, horses pulled the logs through the snow to the roadside. The logs were loaded on sleighs and hauled to frozen lakes and rivers, where they waited to be floated to the sawmill after the ice broke up in the spring.

Russ listened as each tree was felled, the cracking and popping of the hinge of wood breaking at the base of the stem sounding like gunshots, branches snapping as each falling giant gained speed and brushed against neighbouring trees. Finally there came the thunderous “Whoompf!” as the tree hit the ground with explosive force.

It was dangerous job. Frostbite was an ever-present risk, and cuts from the sharp axes were commonplace. But the falling trees themselves presented the greatest danger. They weighed many tons and stood up to a hundred feet tall. The men were forced to stay on the narrow paths of trodden snow or be trapped in the deep snow as the hulks hurtled to the ground. Magnifying the danger was the fact the nearest doctor was in Blind River and medical help in the camp was practically nonexistent.

While everyone knew the work was dangerous, it was still jarring when one of the men was seriously injured. Russ could hear nearby men chopping and sawing at trees. He listened as another lumberjack’s tree began falling. But the snapping and scraping sounds of the falling tree stopped prematurely, leaving an eerie hush in the bush, except for the sound of a man cursing. Perhaps the other lumberjack was careless and left too much wood in the hinge, or perhaps he was nervous when the tree looked like it might fall and hadn’t gone deep enough with his backcut. Regardless of the cause, the tree was hung up, leaning, threatening to fall.

The leaning tree placed tremendous pressure on the remaining wood in the hinge, with thousands of pounds of force pushing on it. The man waited for it to fall, willed it to do so, but it would not break on its own. He would have to release it by cutting into the hinge. It was a dangerous operation, since the weight of the tree leaning on the hinge made it unstable and unpredictable. Russ listened and waited, the sweat leaving a cold trail down his back.

Cursing, the lumberjack approached the tree. Suddenly the hinge cracked, and in one massive release of energy, it snapped free at its base. The butt of the tree kicked back with abrupt explosive force, hitting the man squarely in the chest. It lifted him off his feet, tossing him onto the snow, where he lay limply.

Not able to see the other lumberjack, Russ called out. When no answer came, Russ dropped his axe and ran back up the trail, winding his way through the trees. He found the man lying in the snow, conscious but moaning and unable to move. Other lumberjacks came running through the undergrowth.

The injured man’s screams echoed among the trees as he was carried to the road, his cracked and broken ribs grating together. One of the lumberjacks ran for a sleigh to take him to camp. But since the only help was in Blind River, all they could do was give him rum from the camp stores to help numb the pain for the long ride to town. As the sleigh carried him away, his cries grew faint. No one asked his fate, and no one coming from town brought news. Perhaps it was out of superstition or to avoid showing weakness.

Harvesting and hauling logs continued through the long winter. The melting of the ice roads and spring ice break-up on the rivers and lakes signalled the end of the cutting season and the start of the river drive. The camp foreman asked Russ to stay for the coming river drive. Russ agreed. The extra weeks of work would be easier than the bush work, he thought, and at three dollars a day, the pay was double what he’d earned as a lumberjack. The idea of easy work did not last long.

In the turbulent water, clearing logjams amid the floating river ice, often soaked to the waist in icy water, was far more dangerous than bush work. There was no training for Russ, who simply walked out on the wet, rolling, icy logs, spiked boots providing traction, manhandling the logs to break up jams using only a peevie, a wooden pole with a steel hook and a hinged jaw on the end.

The work required strength to move the logs and agility to balance on their slippery surfaces as they bobbed and rolled. Falling would send a man into the freezing water with tons of floating logs.

Russ was working with several other drivers to free a jam, when one of the men lost his balance and fell among the logs into the near freezing river, dropping his peevie. Russ and other men raced across the logs to help.

“Leave that man — save the peevie!” yelled the foreman, seeing what was happening.

The man was trapped in the water among the floating logs, unable to pull himself out. With his head just at the surface of the water, he was in danger of being crushed between the massive trees or drowning if he ducked his head and the solid mass of logs closed above him. Ignoring the yelling foreman, Russ helped pull the soaking man out of the water. As the foreman cursed them in the foulest language, one of the river drivers threw the peevie he had rescued from the water at the foreman’s feet. Turning his back, the driver went back out onto the logs to resume work. Russ quit the river drive that day in disgust.

Emerging from the bush, he was glad to be heading home. It had been a long winter, with scant news of the outside world reaching camp in the half year he had been there. From infrequent newspapers he knew little had happened in the war, neither side mounting a strong offensive. It seemed as though the dire expectations might have been wrong.

Arriving in Owen Sound in April, Russ was rehired to do summer maintenance on the rail lines for the Canadian National Railway. One person glad to see him was Jack MacLeod. Jack immediately approached him to invite him to the lacrosse team’s coming practice. Later, when Russ arrived at the arena wearing an old practice sweater, Jack came to talk to him.

“Where’s my lacrosse sweater?” Jack asked, surprised Russ was not wearing the team jersey.

Russ hesitated, surprised by Jack’s question. “Your sweater? But you gave it to me. I wore it all winter up north. By spring, it was full of holes and falling apart, so I burned it in the fire.”

Jack could not believe what Russ had said. When Jack’s father, Jim, heard what had happened, he told Russ he would have to replace the sweater. Russ felt this was unfair. The team charged admission to games, Russ played for free, and he refused to buy another sweater.

When the team was selected and Russ was chosen to it, he continued wearing his old practice sweater to their games. He was the only player without a team sweater bearing the Georgians name. Had Jim MacLeod selected the team, the dispute over the sweater might have caused Russ to be excluded. However, the players were selected by the Georgians’ new player-coach, Gerry Johnson. Gerry had been recruited by Jim and came from Hamilton with his wife Marge and their three young children. They had arrived before April to meet the league’s requirement allowing only town residents to play. In return for playing lacrosse, Gerry was provided a house to live in, a job, and was named team captain. Local players, like Jack and Russ, played only for pride.

When the season began, Gerry and Russ were often playing partners on Owen Sound’s defence. Gerry found the younger man dependable and tough, and liked his quiet confidence and subtle sense of humour. Another player, Perry Wilson from Fergus, Ontario, was a slick forward with a good scoring touch. Russ, Gerry, and Perry soon became inseparable. The Georgians entered the season as one of the favourites, their chief rival the team from Orangeville.

Owen Sound was proud of its sports teams, a feeling surpassed only by the community’s feelings for its army regiment, the Grey and Simcoe Foresters. With a war underway, even a “phoney war,” as newspapers had dubbed it, the city’s expectations of the Foresters were high. The town was home to two Great War Victoria Cross recipients, the highest military award conferred by Great Britain. One was Billy Bishop, the British Empire’s top flying ace and by far Canada’s best-known veteran. Owen Sound’s other Victoria Cross had been awarded to Private Tommy Holmes. Holmes was the youngest Canadian to earn the award, given for his bravery at Passchendaele in 1917. Described as frail and delicate, he appeared an unlikely hero. Two Victoria Crosses in a city of eight thousand was almost unheard of, and it created an air of expectation of great things to come from the young men of Owen Sound.

Many of Owen Sound’s men over the age of forty were veterans of the battles of Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele. They had a keen interest in the new war in Europe and strongly felt that Owen Sound’s young men should enlist, as so many in the city had in 1914. However, when Russ returned from northern Ontario in the spring of 1940, the Foresters still had not opened their ranks for enlistment. Russ knew some local men had travelled elsewhere to join up, but many preferred to wait for the Foresters to put out their call for recruits.

Several hundred local men had been training with the militia for months. They marched two nights a week in civilian clothes through the city, led by the drum and bugle band. But the drills lacked a sense of urgency. That changed dramatically on May 10, 1940, when the German army released its Blitzkrieg on the Western Front.

The lightning attack, spearheaded by German armoured forces, smashed the relative quiet and blew massive holes in the static front. German tanks rapidly pushed through weak points in the Allied lines, threatening to encircle bypassed French and British positions. The speed of the German advance and the collapse that followed was so fast and complete, it was barely more than two weeks from its start until the British desperately evacuated their armies across the English Channel from the Belgian port of Dunkirk. By June 14, Paris was occupied, and the world waited for what seemed the inevitable invasion of Britain. It seemed incomprehensible to Canadians that the British and French armies could be so incapable of stopping the Germans.

In that depressing time, when the French capitulated and it seemed Britain might soon follow, there was a feeling that if Britain were conquered, Canada’s future would be in question. This was not a vague threat. In 1938, the Canadian government and the Canadian military’s joint staff committee considered it possible that in the event of war with Germany that Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal would be bombed, and coastal cities like Halifax, St. John’s, New Brunswick, and Quebec City shelled by naval bombardment by the heavy guns of the German navy.[4]

Following Dunkirk, Britain was pushed back to the defence of the island homeland. The badly mauled British army would need years to replace the masses of artillery, tanks, and transport left in France and Belgium. In the air over Britain, Hermann Göring’s Luftwaffe fought to destroy the Royal Air Force, the final step before a cross-channel invasion could take place. In preparation for such an attack, the Germans were gathering ships and barges on the coast to ferry troops, tanks, and guns across the English Channel.

The first Canadian troops arrived in Britain too late to join the battle against the Germans. Though untested in battle, these Canadians carried the hard-earned reputation of their fathers from the Great War as exceptionally tough fighters. More importantly, the Canadians brought with them troop transportation and artillery, and for that they were given responsibility for being a mobile first line of defence in southern England. When the Germans attacked, the Canadians would respond to German paratroop landings inland, and when that threat was dealt with, would rush to the English coast to push back anticipated landings.[5]

Canada’s military command knew their troops would suffer heavy casualties if forced to fight in coming months. There could be no retreat for the Canadians in the event of an invasion, and the reality was, in 1940, Canadian troops in England were just a smattering of permanent force and militia troops, leading mostly civilian volunteers with only a few months of training. They would likely have been annihilated.[6]

In those weeks when the shadow of invasion darkened the British Isles and Canada, the call finally came for more volunteers for overseas service. When things appeared their worst in 1940, there was no shortage of Canadians impatient to enlist.

In early June, the Foresters finally were allowed to call for volunteers. When the volunteer militia gathered for drill practice that week, commanding officer Colonel Tom Rutherford announced they were being disbanded so enlistment for overseas service in the regiment could begin. Those from the militia who qualified, he told them, would get the first chance to sign up, but those under eighteen would have to drop out until old enough. Speculation quickly spread through Owen Sound about which of the young men would show up at the recruiting office.

Early on June 18, Russ and Perry walked to the militia barracks on 14th Street West, barely a five-minute walk from Russ’s house, and joined the line of men waiting to enlist.

Owen Sound was small enough that Russ knew every man his own age by name. Those in line he didn’t know were men from nearby farms and towns such as Wiarton, Meaford, and Chatsworth. There were some locals in line he may have been surprised to see, smaller men and some who were mild-mannered.

Perhaps he was also surprised at who had not shown up. Where were some of the men with a reputation for toughness? Some of the city’s athletes? With Canada and Britain at risk and relying on Canadian volunteers to step forward, it crossed his mind that he may have underestimated some and overestimated others. Finally Russ and Perry reached the front. They sat beside one another, each with one of the Foresters’ permanent force NCOs, who oversaw their filling out the enlistment form. In a few minutes they were done and were told anti-climactically they would be contacted shortly.

The following Wednesday, Russ and Perry reported back to the barracks. The list of men who had signed papers had been winnowed down, and it was time for those selected by the Regiment’s officers to go through a medical inspection. Russ and Perry were told to strip to their underwear. They stood in their boxer shorts with the other enlistees, waiting to be examined by a doctor. It was a straightforward eye-ear-nose physical exam, testing of reflexes, and listening to heart and lungs. Russ and Perry passed the Medical Board and were sent to the hospital for a chest X-ray. Once it was confirmed there were no signs of lung disease, their enlistment was finally official. Returning to the barracks with the results of their X-rays, the army’s rough reward was an inoculation against typhoid, a thick needle punched under the skin on the chest.

Not everyone who tried signing on was accepted. More than a third of those enlisting in Owen Sound were turned down: In the first week, one hundred eighty men signed up and sixty-nine were rejected. Some were turned down for medical reasons, others were eventually excluded because the officers did not want them in the regiment.[7] It was normal to think the biggest and most brawling local men would be most sought after. But this was not the case with the Foresters. Potential troublemakers were well-known and moved out. Whether such decisions made sense to the community, or even followed military protocol, didn’t matter to Colonel Rutherford. He had seen first-hand during the Great War that discipline and a sense of devotion to comrades were more important than mere physical strength. If an example was needed, he could point to Tommy Holmes, one of the youngest, smallest, and bravest men from Owen Sound to fight in the Great War. The officers also knew that if those they turned down were serious, they could enlist elsewhere. The officers kept only those they considered the best of Owen Sound’s young men.

There was a third group of men in town. These were single men who were physically capable and of the right age, but who chose not to enlist. It is hard now to say whether pressure was placed on such men to enlist, but it would not be surprising. There would be instances in Canada of men not in uniform being openly called “yellow” or “chicken.” Sometimes such disdain was aimed at men who had tried to enlist but were medically unfit. Harassment became severe enough that an “Applicant for Enlistment” badge would be issued in 1941, given to those who had volunteered but been judged not fit. They were told to wear the badge on their lapels to avoid embarrassing public encounters.

After passing his medical, Russ quit his job with the CNR and went under pay with the army. He and Perry received uniforms they were to wear at all times when in public. They were among the three hundred and fifty men from Owen Sound accepted by the Foresters Active Force, volunteers to travel overseas. It had taken only a few weeks to fill the Foresters Active Force Company. There was also enlistment in a Foresters’ Home Force, mainly filled by older men who joined with the promise that they would not be sent outside North America.

At seven a.m. daily, they reported to the barracks in uniform for training. In large measure, this consisted of hours spent on the parade square. Being a rifle battalion, the Foresters were taught the quick march: one hundred forty paces per minute — each pace about thirty inches long, with arms swinging to the height of the breast pocket. As the recruits learned to perform simple march steps in unison, increasingly intricate drills were introduced.

“Squad, move to the right in threes, right — turn, by the left, quick — march!” echoed across the parade square outside the Owen Sound barracks. This was not the movie portrayal of an army drill, where profanity and sarcasm were hurled at left-footed recruits by drill instructors. Instead, there was a professional and sharply given series of instructions. After initial curiosity and some amusement at the exaggerated drill movements, many recruits probably wondered why the army kept them practicing drills when soldiers were supposed to be taught to fight. There was no doubt the army took drill very seriously. Even if it had been explained that drill was a way of instilling discipline, pride, and the cohesion needed for success in battle, to the young men the repeated practice of the same routine over many hours was almost certainly a disappointment. What seemed needless attention to detail on the parade square was seen by their officers and non-coms as instilling qualities needed to endure the stress of war. In the army’s view, the skill with which a unit drilled was a direct indication of the skill of the troops and their officers.[8]

Russ photographed beside his home in Owen Sound shortly after enlisting with the Grey and Simcoe Foresters.

The Foresters lacked room to house all the new troops, so men from town stayed at home overnight, while recruits from the surrounding towns and countryside stayed in the barracks. Owen Sound now had a military feel to it, as the more than five hundred men in the overseas and home service units were required to wear their uniforms at all times. The feeling that Canada was at war was unmistakeable.

Russ and Perry arrived at the arena for the Georgians’ next home game following a full day of training. For the first time they arrived in their army uniforms. It gave a different feeling to the dressing room. Since the Foresters began recruiting, local men on the team now fell into two categories: those who had enlisted and those who had not. When Russ and Perry took to the floor and looked into the stands, there too they saw men in uniform peppered among the spectators. There was a filter now separating them from those not in uniform. The Georgians easily defeated the visiting Burlington club. Perry was quick on his feet, darting tirelessly through the opposition defence, while Russ was reliable stopping opponents who ventured toward Owen Sound’s goal. Their team had so far only been beaten twice this season, both times by Orangeville, the league leaders. After the game, Perry, Gerry, Jack MacLeod, and several other Georgians players dropped by the Colombo house. They sipped rye whiskey on the front porch. Their voices and laughter grew louder as they relaxed. Before long Blanche came outside, and they fell silent.

“Oh, Sweet,” she said to Russ, “could you and your friends be a little quieter. I’m afraid you are going to disturb the neighbours.” Addressing the others she said, “It’s so nice to see you boys. I don’t know why Russel never brings his friends home.” Russ turned his eyes towards the ceiling as she went back inside.[9]

The silence was palpable as Russ’s friends and teammates looked at each other.

“Sweet?” one of the players was barely able to get out before breaking into hysterical laughter.

“Sweet!” the others took up the refrain. “Sweet!” they repeated over and over, howling with laughter. Twenty-four-year-old Russ wondered what his mother could have been thinking. Inside, Blanche heard the laughter and was glad that Russ was having such a good time with his friends.

The following Saturday, at seven a.m. sharp, the Active Force Foresters from Owen Sound arrived at the barracks with an army knapsack holding personal belongings. They boarded twenty trucks and travelled in convoy to Camp Borden, escorted from Collingwood by two Royal Canadian Air Force planes.

Camp Borden was the country’s major army base and home to Canada’s largest military airfield. Driving into the camp that Saturday afternoon, the Foresters entered a small military city, with dozens of huts and barracks, fifteen thousand soldiers, and fields filled with hundreds of tents. Feelings among the arriving recruits were mixed. Some felt they were at the start of an adventure, others wondered what they had gotten themselves into, and some were already homesick. As the trucks stopped, and the men jumped out, the Foresters saw a small village of tents erected by their advance party. Arranged with precision in rows and columns, the tents were allocated to the four companies comprising the Foresters: Company A from Owen Sound; B Company from Barrie; C from North Bay, Kirkland Lake, and Timmins; and D Company from Sault Ste. Marie and Sudbury.

The men were taken to the camp storehouse where they were issued a blanket and a straw-filled mattress called a pallaise. Soon after, the Foresters’ mess tents were opened and the men received their first army meal.

That evening there was time for reflection, and it began sinking in that they had committed themselves to a way of life ending most personal freedoms. Some were undoubtedly having second thoughts, but those were by and large kept to themselves. Despite orders to the contrary, liquor bottles appeared from soldier’s knapsacks, and as the evening wore on it helped turn the mood more cheerful. A recruit was hoisted onto the roof of one of the latrines by his mates and began singing. Foresters strolled over for the impromptu concert, a crowd forming and joining in the songs. It helped relieve some of the melancholy, and the officers, sitting in their mess, took it as a good sign as the men strolled back to their tents singing “Pack Up Your Troubles.”[10]

The next day Russ woke at six a.m. to the harsh blaring of a trumpet playing reveille. A sergeant yelled they had an hour to wash, shave, eat, and then assemble for an address by the colonel. The thousand men rushed about and assembled at the appointed time in their platoons on the crowded parade ground. They were inspected by their officers, and then Colonel Rutherford took his place in front of them. He told his second-in-command to have the men stand easy. The thousand men spread their legs shoulder width and relaxed, their arms at their sides, eyes focused straight ahead.

The address lasted more than an hour in the hot Sunday morning sun. Rutherford spoke of his expectations for them, and what their expectations should be of one another. He told them of the need for “comradeship, cooperation, cleanliness, and good conduct.” Rutherford had been a lieutenant with one of Owen Sound’s regiments in the Great War, and he told them of the camaraderie shared by the men he’d served with. He described the training they would undergo, from map reading to marksmanship. He would stand by them as their commanding officer, just as he expected each of them to stand by him and their fellows in representing the regiment.

The next weeks were filled with activities intended to turn the civilian recruits into soldiers. The days were spent with marching drills, rifle practice, and skewering with bayonets straw dummies strung from wooden gibbets.[11] After four weeks, the men seemed transformed. Their faces were tanned from the outdoor exercise, and they were already well-schooled in military discipline. However, the novelty of camp life had worn off.

By the middle of July, after a month sleeping in tents, the Foresters moved into newly constructed huts. Bugle reveille at six a.m. was followed by a rush to be one of those fortunate to shower before the supply of hot water was exhausted. The men shaved shoulder to shoulder at long galvanized tubs, hot and cold taps spaced every few feet. They arrived to stand in line for breakfast with their metal dishes. Each man had to eat and put his part of the hut in order before the bugler’s call-to-parade at eight a.m. Blankets, pallaise, extra uniforms, personal belongings, and dishes had to be arranged in neat rows along the centre of each hut. After daily inspection, the officer in charge awarded a flag for the most orderly hut. That flag was displayed for long periods on the hut belonging to Owen Sound Company’s segregated platoon of Native American soldiers, volunteers from the Cape Croker Reserve north of town.

Every morning except Sunday, the men assembled in the parade ground for inspection, followed by callisthenics until nine. Most days they marched in the parade ground from nine until noon. Training resumed after lunch, sometimes at the rifle range. At other times it might be a lesson in semaphore or a route march through the countryside.

In the few hours of free time in the evenings, many went to one of Borden’s regimental canteens. Located near the Foresters’ section of the camp, the Salvation Army hut was a popular place to write letters home, sit and talk, watch movies, or listen to a visiting band. By ten, everyone was back in their hut for lights out at 10:15. But often lights out was short-lived, as moments after the orderly officer made his rounds, the bulbs strung the length of the hut were switched back on to resume poker games.

Russ found the physical challenges of life at Camp Borden easy compared to the tough winter at McFadden’s camp. But the mental challenges of the army were different than those in civilian life. After eight years of manual labour jobs, Russ must have grown used to taking direction from those who might be more experienced but lacking his bright mind. To not suffer fools in civilian life was possible if you were prepared to walk away from a boss who proved intolerable. But a lowly army private displaying that attitude almost certainly found himself in trouble.

Compounding Russ’s rebellious attitude towards mindless authority was the fact that he was sensitive about not having completed high school. With a sharp mind, he could derive pleasure from demonstrating that education and rank didn’t necessarily translate into superior intellect. He may already have adopted the fractured Latin phrase he espoused in later years: “Illigitimus non carborundem est.” For those not familiar with the saying, he would translate it: “Don’t let the bastards grind you down.”

Even in a regiment as forgiving as the Foresters, where building esprit de corps was considered more important than crisply saluting every passing officer, Russ likely found use for his Latin maxim. He was, after all, not part of the permanent army, and must have at times found the army’s insistence on arcane military protocol akin to water torture. It was hard for most recruits, much less one who was sharp-minded and of a rebellious spirit, to see how the manner a blanket was folded, or the very precise arrangement of personal items in a footlocker, was going to help win the war.

Alcohol was not allowed in the barracks, but it was practically impossible to prevent it. On a few occasions Russ consumed more than someone should who had to rise early the next morning. Once, after he fell into an alcohol-aided sleep, someone put a chocolate bar down the back of his shorts. The next morning, Russ realized there was a sticky mess. His reaction to what he thought had happened more than satisfied the perpetrators.

On another occasion, he woke with a pounding hangover. Staggering out of bed after the six a.m. reveille, he pulled on his uniform and stumbled onto the parade square. He groaned inwardly when the Sergeant told them to report back with packs and rifle. They were going on a ten-mile run.

With packs on their back and rifles in their hands, Russ’s platoon left the parade ground at a slow run. His legs felt like lead weights were attached to them and the pack jarred with each step. Soon others began passing him, then he was running by himself. He continued, his head feeling like it would explode. With his eyes fixed on the ground Russ became aware that someone had dropped back. Glancing up, he saw Perry.

“How are you feeling, Russ?” he asked.

“Words won’t do it justice,” Russ said.

“We’ll go together,” said Perry. Russ grunted in reply as the pair ran, the platoon pulling further ahead of them. As they slowly trod on, it seemed as though Russ might make it. But both knew what lay ahead. Rising before them in the distance was a steep hill. Reaching the bottom of it, Russ stopped.

“I’ll never do it,” he said, leaning forward and gasping for breath. He dropped his pack and rifle and fell to his knees.

“Wait here,” said Perry. He picked up Russ’s pack. Carrying both packs and two rifles, he proceeded up the hill. Within a few minutes he was back.

“Climb on my back,” he said.

“What? You’re crazy! Leave me here to die.”

“C’mon, you sunovabitch. If you don’t finish this run, you’ll never get your pass for this weekend. We have a lacrosse game we promised to play, and you are going to be there.”

Russ looked up at his friend, standing over him with his hand extended. Grabbing onto it, he pulled himself upward. As he did, Perry went down on one knee and pulled Russ over his shoulders, wrapping his arm around Russ’s leg and balancing his friend’s weight across his shoulders. Grunting, Perry stood up and began climbing the hill. Step over step he carried Russ forward. When he reached the top, the two men collapsed in the grass. Perry started laughing, and soon the two of them were lying on their backs, howling like schoolboys.

After a few minutes, they climbed to their feet and put their packs on. When they reached the parade ground, the rest of the column had long since arrived and been dismissed. They went to find the Sergeant, who briefly studied them, saying nothing to the troopers before dismissing them.

Relief from army discipline, close living quarters, and mediocre food came every other weekend when passes were issued. Most of the thousands of soldiers and airmen boarded trains for Toronto, where hostels were cheap and entertainment plentiful. Many of Owen Sound’s Foresters headed home. Russ and Perry used their weekend passes to join the Georgians wherever they were playing.

Sometimes, someone from the team would come by with a car to pick them up. At others they drove to the game in the Colonel’s personal car, which he loaned them. Perhaps the Colonel felt it would boost morale to have two of the Owen Sound Company playing for the hometown Georgians.

The lacrosse season had been exciting. After falling behind Orangeville early in the year, they had clawed their way back, finishing tied in points. In a two-game series to choose an overall winner, Owen Sound won both games, entering the playoffs as regular season champion. The Georgians won their first-round playoff, progressing to the final against Orangeville. The Georgians won the first game of the series in Owen Sound, but Orangeville struck back to take game two at home. They exchanged wins at home in the next two games, setting up a fifth and deciding game in Owen Sound. Perry and Russ were in Owen Sound to take part in the league final on September 5. Two thousand fans packed the arena, and they tensely watched the close contest. They were able to relax and enjoy the game in the second period, when with Perry up front and Russ and Jack MacLeod on defence, Owen Sound scored nine unanswered goals to burst the game open. Despite missing their star player, Gerry Johnson, who was injured, the Georgians went on to an overwhelming 32–13 win and the series victory. They would next enter the provincial playdowns.

In a team picture taken on the floor of the arena after the final game, Russ wears the practice sweater he’d used all season, the rest of the team in striped team jerseys bearing the Georgians name. Wives and girlfriends waited outside the arena for the Georgians to shower and dress. Gradually the players came out, each wearing a new team jacket. When Gerry, Perry, and Russ emerged, Russ and Perry in their army uniforms, carrying team jackets, Gerry without one. Gerry’s wife Marge knew from the looks on their faces something was wrong. Later that evening Gerry explained.

After winning the championship, Jim MacLeod had entered the dressing room carrying a large box. He called for the players to be quiet and gave a short speech, thanking them for their hard work and for such a fine season. Then he opened the box and from it took a Georgians team jacket. The players saw the team name embroidered on a crest. The jackets were a token of gratitude from team management, he explained.

Jim threw the jacket he was holding to the nearest player. Reaching into the box he took out another jacket, throwing it to the next man. Jim threw a jacket to each man in turn as Russ waited his turn. Perry, sitting to Russ’s right, caught his. But as Russ readied himself to catch the next jacket, it was not thrown to him. It went to the man on his left. The players fell silent as everyone looked at Jim and then at Russ.

Gerry watched as Jim continued tossing the jackets to the remaining players; he knew about the disagreement over the sweater. Finally Jim reached the last player on his right. It was Gerry. The room was silent as Jim kicked the now empty box into the centre of the room. Saying nothing, Gerry walked across the room and handed his jacket to Russ.[12]

The Georgians’ opponent in the provincial semi-finals was the team from Brooklin, a town near Oshawa. Russ and Perry continued appearing at the Georgians games, made possible by Colonel Rutherford approving their leave from Camp Borden. Owen Sound beat Brooklin in three straight games. It qualified them to play for the provincial Senior B Lacrosse Championship against Sarnia. Everyone expected the series to be their toughest challenge.

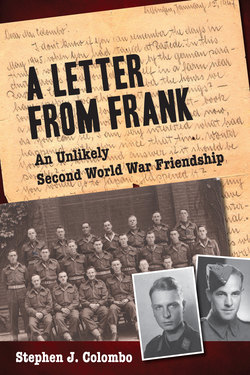

The Owen Sound Georgians lacrosse team, on winning the Ontario Senior B Championship in 1940. Back row, left to right: Roy “Sally” Tyler (trainer), Andy Blair, executive members Bill Gilligan, Charlie Gagan, Charlie Peacock, Ted Manners, and Harry Ashcroft, Jack MacLeod, and manager Jim MacLeod. Middle row, left to right: Bun White, Ken MacLeod, Russ Colombo, John McConachie, Harvey LeBarr, Orville McDonald. Front row, left to right: John Standeaven, Fred Smith, Gerry Johnson, Chuck Harden, Jack Fletcher, mascot Bud Rush, Tommy Burlington, Hiram Dean, Perry Wilson, Maurice Cassidy.

(Photo courtesy of the Owen Sound Sports Hall of Fame)

After nearly three months at Camp Borden, the regiment’s officers decided to take the Foresters on the road. It would allow the regiment to practice moving across country and give the men a few days break from camp life, showing off their training in their hometowns. The Foresters marched through Barrie, Orillia, Midland, and Collingwood that first day. In each town, a thousand soldiers jumped from the trucks and marched down the town’s main street, greeted by cheering crowds at each stop.

While the Foresters spent the night in tents in Collingwood, Russ and Perry left to play lacrosse in Owen Sound that evening. The Georgians easily won the opening game in the best of three series, beating Sarnia 24–5. The crowd in the arena, packed to standing room capacity, cheered their team as the time clock ticked off the seconds.

The next morning, the regiment paraded at the Indian Reservation at Chippewa Hill. Foresters from Owen Sound were excited at their chance to parade in front of friends and family. They had come a long way from the group who had left town a few months earlier. Their arrival was also anticipated by the people of Owen Sound. For the first time the town was going to see its sons parade in uniform. Anyone with a Canadian Red Ensign, Canada’s national flag, had it hanging in front of their home, businesses decorated their stores and put out their flags, and children were let out of school to attend the parade. The city and local businesses took a full page in the local newspaper to welcome the Foresters, with the message:

Now, after nearly three months of strenuous training at Camp Borden, the Battalion is coming back to visit. Owen Sound, the home of many of the Grey-Simcoe officers and men is mighty proud of this Regiment and we know every man will live up to the splendid traditions and achievements of the famous 147th and 248th Regiment in the last war. Thrilling with pride Owen Sound extends a royal welcome and wishes every one of these men the Best of Luck and God’s Blessings when they go forth to battle a ruthless foe threatening our Homes and Civil Rights.

The Foresters arrived in Owen Sound early in the afternoon. Russ and Perry were waiting when they arrived. When the regiment began to march, it was led by Colonel Rutherford, followed by the drum and bugle band, and then the troops, who marched in their platoons, each man with a rifle on his shoulder. People stood three and four deep along the main street, applauding, waving and calling greetings to soldiers they knew. Young boys on bikes made an impromptu addition, riding back and forth along the column of soldiers. Children waved small Canadian flags and cheered the soldiers parading past. It was a stirring sight, the Regiment stretching for blocks, marching three abreast, each with one arm swinging to breast pocket height, the other holding the butt of his rifle, a thousand boots striking the pavement in unison sounding like drums.

Marching with his platoon, Russ heard his name called several times as the parade wended through town. Then he heard his mother’s voice calling. From the corner of his eye, he saw her and his brother Jack. It was hard to say who was prouder, the people of Owen Sound whose young men had been transformed into soldiers, or the men marching proudly in front of family and neighbours.

As the regiment reached the end of the parade route, it continued marching south to Harrison Park. Waiting trucks took the soldiers to the barracks on 14th Street West, where the men fanned out towards their homes or downtown.

Russ and Perry walked together, greeted by friends and acquaintances. Perry, who was from Fergus, was invited to stay with Russ. During dinner they told stories of life at Camp Borden. Later, the two soldiers slipped out of the house and made their way to Gerry and Marge Johnson’s home, stopping to buy a bottle of whiskey. Although Prohibition had ended in Ontario more than a decade before, a city plebiscite had kept Owen Sound a dry town. Nevertheless, Russ and Perry had no problem buying liquor, since bootleggers’ houses were well-known throughout town.

It was early in the morning when they returned home. Russ hoped his brother’s snoring would cover the creaking wooden stairs. Perry proceeded to the bedroom on the third floor. Russ went to his room on the second floor and was asleep almost before his head touched the pillow.

His eyes flew open after what seemed an instant. Light streamed through the window and Russ reached for his watch. It was seven thirty, and he knew the Foresters had boarded their trucks at seven and left town. He and Perry were instead headed to the next game in the series that evening in Sarnia as the Foresters continued their tour to other towns in the district.

Sarnia took the early lead before Russ replied with the Georgians’ opening goal, halfway through the first period.

“Russ Colombo and Johnny Standeavan started the ball rolling in the first period, when trailing 2–0, the two players combined on a lovely passing attack to sink the first Owen Sound goal,” the Sun-Times reported.

When the Georgians finally took the lead, Sarnia all but collapsed. The Georgians won 15–9.

“One of the Owen Sound players who couldn’t be stopped last evening was Perry Wilson,” said the paper. “… Wilson picked up a pair last night, but he went like a million dollars all through the game. Jack MacLeod with a pair of goals and a like number of assists turned in a good game for the winners … (and) coach Gerry Johnson formed the backbone of the club’s powerful … defence.”

It was Owen Sound’s first Ontario Lacrosse championship in thirty years, and the players were greeted as returning heroes.

Thanksgiving weekend was a three-day leave for most of Camp Borden. Like many Foresters from Owen Sound, Russ made his way home, joined by Perry. But instead of returning Monday night when his leave was over, Russ and Perry showed up at Gerry’s house. They were staying a few more days. As their absence stretched to Wednesday, the provosts began searching for them, phoning Blanche, asking if she knew where Russ was. He was constantly on the lookout for provosts. When Russ appeared at Gerry’s house, he asked if the provosts had come looking for him there. It was cloak-and-dagger in Owen Sound.

When Russ woke Sunday morning, he was five days late returning from leave. He relished the luxury of relaxing a moment longer without a bugler’s reveille shattering the peace. When he came out of this room, he called to Perry, who was already coming downstairs. The smell of breakfast had woken them. As they sat down at the kitchen table, Blanche asked how long they were staying. Russ told her they were heading to Camp Borden later that day. He didn’t tell her they had been AWOL since Monday.

Later that day they decided to go downtown, wearing their uniforms as military protocol required. They split up, agreeing to meet for coffee in an hour.

However, Russ and Perry were not the only Foresters in Owen Sound. Russ was just across the 10th Street Bridge when he heard someone shout, “There’s one of ’em!”

Russ heard the sound of army boots striking the pavement. Looking behind, he saw two provosts running towards him. He instinctively began running and people stopped to watch the humorous sight of three soldiers in a footrace through downtown. Someone called out encouragement to Russ, while others laughed.

Russ raced towards a phone booth. Close behind came the provosts, and Russ barely closed the phone booth door before they arrived. Inside, he put his legs up, holding the door closed with his feet, his back braced against the phone booth wall. One of the provosts put his shoulder to the door to force his way in, while the other yelled at Russ to come out. Russ’s legs barely budged. Coolly, he reached into his pocket and pulled out a handful of coins, from which he took a nickel. Lifting the receiver while the provosts continued hammering at the door, Russ reached behind his head, inserted the coin and dialled.

The phone rang. “This is Russ,” he said to his mother.

“Sweet … what is that noise?” she asked.

“It’s a couple of friends from the army,” he said. “It looks like I’m going back to Camp sooner than I’d thought.” Russ tried to talk calmly.

“When will you be leaving?”

“I doubt I’ll be able to get back to the house. So I’ll say goodbye now.” He hung up and lowered his legs. The provosts, who had stopped trying to force their way into the phone booth, waited for him to emerge. Each took Russ by an arm, down the street, past the restaurant where Russ and Perry were to meet. Russ saw Perry laughing through the restaurant’s curtain.

The provosts escorted Russ to a nearby parking lot, where several other Foresters were in the back of an army truck. “Climb in, we’re leaving,” one said. As the truck turned the corner heading towards the hill out of Owen Sound, they heard someone yelling and saw a soldier running after them. He slowly gained on the accelerating truck. He leapt, and those in the back pulled him the rest of the way in. The soldier came to his feet. It was Perry, and he was still laughing.

Once at camp, Russ, Perry, and the other AWOL soldiers received punishment — normally a day confined to barracks and loss of pay for each day’s absence. For this extended absence Russ may have been given additional punishment — perhaps this was the time he was told to report to the drill hall with his toothbrush, where he was instructed to get down on his hands and knees and use it to scrub the floor of the cavernous room. If Russ’s long absence was surprising, what followed in a few months surpassed it. In April 1941, he was appointed batman to the regiment’s commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Rutherford.

Becoming batman to the commanding officer was an honour. It would not have been given lightly, and must have reflected in some measure Russ’s achievements in training. The appointment would help shape the remainder of his military service.

Being a commanding officer’s batman is an appointment that is highly sought after. It can lead to quick promotion, but in the Foresters, it meant much more. Colonel Rutherford was greatly respected by his men, who had affectionately dubbed him “Uncle Tom.” One of the Colonel’s sons said his father felt towards the Foresters the way a father does towards flesh-and-blood sons,[13] and the affection was widely returned. Russ’s choice as the Colonel’s batman was no small matter.

Russ took charge of the Colonel’s personal and professional needs, cleaning and pressing his uniforms, straightening his quarters, delivering messages, and anything else the Colonel needed. At the same time, Russ was required to perform well in all the training and exercises. Not doing so would have been an embarrassment to the Colonel.

On December 21, 1941, the Foresters were granted a two-week Christmas furlough. Most of the camp emptied. For Canadian families with soldiers home on leave, this Christmas was tinged with thoughts of the war. The Luftwaffe filled the air over Britain, and German submarine Wolfpacks roamed the North Atlantic, hunting Canadian ships carrying aid vital to the beleaguered island nation. The threat of an invasion remained high, and in the back of every Forester’s mind was the knowledge that the regiment might soon be sent to England, and this could be their last Christmas at home for years to come.