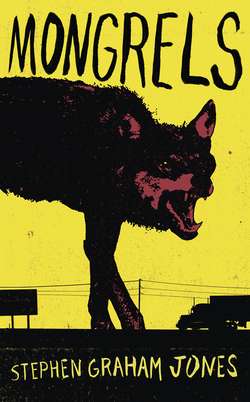

Читать книгу Mongrels - Stephen Jones Graham, Стивен Джонс, Стивен Грэм Джонс - Страница 10

CHAPTER 4 The Truth About Werewolves

ОглавлениеBut this is for class.”

The reporter doesn’t start with this. This is where the reporter finally gets to.

The reporter’s second-grade teacher said interviewing a family member would be easy.

Teachers don’t know everything.

The reporter’s uncle has been awake, he says, for sixty-two hours now. To prove it he holds his hand out to show how it’s trembling, at least until he wraps it around the top of a make-believe steering wheel.

This is right before the move back to a different part of Florida in the nighttime. This is Georgia homework.

“Just do it already,” the reporter’s aunt says to her brother. She’s in the kitchen rehabbing the stove, trying to coax Christmas from it.

The reporter’s uncle drags the weak headlights of his eyes in from the road he can still see, settles on the blue spiral notebook the reporter’s holding.

“You really want an A?” the uncle says. “An A-plus, even?”

In the kitchen the aunt clears her throat with meaning for the uncle. The reporter’s already up past his bedtime for this assignment.

So far she’s pulled two melted Hot Wheels from the oven. They don’t roll anymore.

“If he doesn’t pass school—” she starts, her voice as big as the inside of the oven, but cuts herself off when her fingertips lose whatever it is they’ve latched on to. Another Hot Wheels?

“I remember school …” the reporter’s uncle says, his voice dreamy and half asleep. Like it’s dragging out across the years. “You know the ladies love our kind, don’t you?” he says, talking low so his sister won’t have anything to add.

“I’m supposed to ask you the questions,” the reporter says, his lips firm.

Because he lost his sheet of interview questions, he’s made up his own.

“Shoot,” the reporter’s uncle says, yawning so wide his jaw sounds like it’s breaking open at the hinge.

“Why do you always pee right before?” the reporter asks, no eye contact, just a ready-set-go pencil, green except for the tooth marks. It’s from the box of free ones the teacher keeps on the corner of her desk.

“Pee?” the uncle says, interested at last. He looks past the reporter to the kitchen, probably with the idea that the reporter’s aunt is going to prairie-dog her head up about werewolf talk.

No such aunt tonight.

The reporter’s uncle shrugs one shoulder, leans in so the reporter has to lean in as well, to hear. “You mean before the change, right?” he says.

Right.

“Easy,” the uncle says. “Say—say you’ve got a pet goldfish. Like, one you’re all attached to, one you’d never eat even if you were starving and there was ketchup already on it. But you have to move, like to another state, get it? ‘State’? You don’t put the whole fishbowl all sloshing with water up on the dashboard for that, now do you?”

“You put it in a bag,” the reporter says.

“Smallest bag you can,” the uncle says. “Makes the trip easier, doesn’t it? Shit doesn’t get spilled everywhere. And the fish might even make it to that other state alive, yeah?”

In his notebook, angled up where his uncle can’t see, the reporter spells out fish.

“But, know what else?” the reporter’s uncle says, even quieter. “Wolves, werewolves like us, we’ve got bigger teeth to eat with, better eyes to see with, sharper claws to claw with. Bigger everything, even stomachs, because we eat more, don’t know when the next meal’s coming.”

In the reporter’s notebook: four careful lines that might be claw scratches.

“Bigger everything but bladders,” the uncle says, importantly. “Know why dogs always end up peeing on the rug? It’s because a dog can’t hold it. Because they’re not made to be inside. They’re made to be outside, always peeing all over everything. They never had to grow big bladders, because there’s no lines to wait in to get to pee on a tree. You just go to a different tree. Or you just pee where you’re already standing.”

“But werewolves aren’t dogs,” the reporter says.

“Damn straight,” the uncle says, pushing back into the couch in satisfaction, like he was just testing the reporter here. “But we maybe share certain features. Like how a Corvette and a Pinto both have gas tanks.”

A Pinto is a horse. A Mustang is a car.

In the notebook: nothing.

“So what I’m saying,” the uncle says, narrowing his eyes down to gunfighter slits to show he’s serious here, that this really is A-plus information, “it’s that, if you shift across with like six beers in you, or six cokes, six beers or cokes you already needed to be peeing out in the first place, then you’re going to be trying to fit those six cokes into a two-beer fish bag, get it?”

The reporter is trying to remember what the next question was.

“We got any of those balloons left?” the reporter’s uncle calls into the kitchen, for the demonstration part of this lesson.

Balloons? the reporter writes in the notebook in his head.

His aunt answers with a rattle on the linoleum: Hot Wheels number three. This one rolls into a chair leg, is the best of the lot, the real survivor.

“Corvette,” the reporter’s uncle says, nodding at that little car like it’s making his case for him.

Before the reporter can remember his next question, the aunt comes slipping around the half-wall counter between the kitchen and the living room. Her hand is on the top of the half-wall counter for her to swing around, and her bare feet are skating, rocking the chairs under the table, two red plastic cups that were on the table knocked into the air and, for the moment, just staying there.

In this slowed-down time, the reporter looks from them all the way across to his aunt. Her face is smudged black with a thousand pieces of burnt toast, and there’s a look in her eyes that the reporter can’t quite identify. If it were on a test, the kind where you have to put some answer to get partial credit, what he might write down is “reaching.” Her eyes, they’re reaching.

Her feet, though.

That’s what the reporter can’t look away from.

They’re not slipping anymore now, just only one step later. They’re gripping. With sharp black claws.

Before he can be sure, time catches up with itself and she’s flying across the coffee table, her whole entire body level with the floor, her arms collecting the reporter to her chest and then crashing them both into the reporter’s uncle, who only has time to make his mouth into the first part of the letter O, which is just a lowercase O.

The three of them are halfway over the back of the couch when the spark the reporter’s aunt must have seen in the blackness of the oven does its evil thing and the whole kitchen turns into a fireball that blows all the windows in the trailer out, that kills all the lights at once, that leaves the three of them deaf against a wall, feeling each other’s faces to be sure they’re all right, and if there are any real answers about werewolves, then it’s a picture of them right there doing that, a picture of them right there trying to find each other.