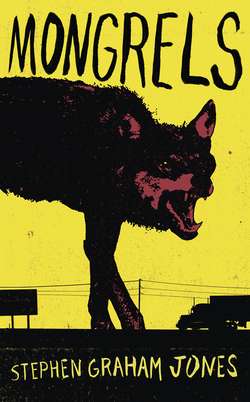

Читать книгу Mongrels - Stephen Jones Graham, Стивен Джонс, Стивен Грэм Джонс - Страница 9

CHAPTER 3 American Ninja

ОглавлениеWe were in Portales, New Mexico, just long enough for me to wear a dog path between the back door of our trailer and the burn barrels. That’s what Darren called it when he came through, and then he’d punch me in the shoulder and get down in a fighting stance, his shoulders curled around his chest like he was a boxer, not a biter. Sometimes it would turn into a wrestling match in the living room, at least until a lamp got broke or Libby’s coffee got spilled—I was twelve and tall by then, needed a yard to wrestle in, not a living room—and other times I’d just hike another half-full trash bag over my shoulder, slope out the back door again.

Because night was falling. Because night’s always falling, when you’re a werewolf.

There were eighty-nine steps to the burn barrels.

And it wasn’t a dog path.

That was just Darren funning me about not having shifted yet. It was probably supposed to be him reminding me not to worry, that I was like him, I was like Libby, I was like Grandpa.

It didn’t feel that way.

I didn’t mind the trash runs, though.

You can always tell who might be a werewolf by if they’re careful like we are, to take the trash out each night, even if it’s just a little bit full. Even if it’s just wasting a trash bag. But I wouldn’t waste them. I’d upend the day’s leavings into the flaky black drums, tuck the white bag into my pocket, use it again the next day.

What I was doing was making deals. With the world.

I’ll take care of you, you take care of me, cool?

Darren had told me that the first time he shifted it was three years early, and that had triggered Libby to shift, and my mom, she hadn’t even flinched, had just stood and pulled the kitchen door shut so they couldn’t get out, and then cornered Darren and Libby with the business end of a small broom until Grandpa got home.

Three years early would put Darren and Libby at about ten.

I was coming in late, it looked like.

If ever.

Libby never said it out loud, but I could tell she was pulling for “never.” She didn’t want her and Darren’s life for me—moving every few months, driving cars until they threw a rod then walking away from them to the next car. She wanted me to be the one who sneaked through without getting that taste for raw meat. She wanted me to be the one who got to have a normal life, in town.

We’re werewolves, though.

Each night at dusk one of us leans out the door to burn the trash, just because we all know what can happen if that trash is left in the kitchen: Somebody’ll go wolf in the night, and because shifting burns up every last bit of fat reserves you have and even leaves you in the hole for more, the first thing you think once you’re wolf—the only thing you can think, if you’re just starting out—is food.

It’s not a choice, it’s just survival. You eat whatever’s there, and fast, be it the people sleeping around you at the rest stop or, if you’ve got a trailer rented for four months, the kitchen trash.

It sounds stupid, but it’s true.

When we first open our eyes as werewolves, the trash is so fragrant, so perfect, so right there.

Except.

There’s things in there you can’t digest, I don’t care how bad you are.

Ever wake up with the ragged lid of a tin can in your gut? Darren says it’s like a circle-saw blade, in first gear. But it’s only because you’re so delicate in the morning, so human. Even a twist tie can stab through the lining of your stomach.

The wolf doesn’t know any better, just knows to eat it all, and fast, and now.

Come daylight, though—so many werewolves die this way, Libby had told me once. So many die with a broke-tined fork stabbing them open from the inside. With a discarded but whole beef rib pushing through their spleen, their pancreas. She said she’d even heard of somebody dying from a house dog that had had its pelvis put together with a metal rod. That metal rod, it went down the wolf’s throat fine, along with the crunchy domestic bones, but in the morning, for the man, it was a spear.

Libby had stopped meaningfully on spear, settled me in her stare to make sure I was paying the right kind of attention.

I had been. Sort of.

Because I was sure I was going to shift just any night now, was going to pad on all fours down the long hall from my bedroom at any moment, sniff at the coffee table then turn my attention to the much richer scent of the kitchen—because that was definitely going to happen, I always lugged the trash out. Never mind that Libby’d always been careful to not leave steel wool or bleach containers in there. Never mind that we kept a jug of black pepper right there on the counter, to sprinkle onto the trash as it built through the day.

I’d be able to smell through that, I knew.

I was going to be that kind of werewolf. In spite of Libby’s prayers.

The life she wanted for me, it was the life my mom should have had, the life that, her not being a werewolf, should have been mine by birthright. But something had gone haywire. Just once, or just waiting, though? That was the part her and Darren couldn’t figure. I had the blood, but was that blood ever going to rise again, or had it been a onetime thing? With Grandpa five years gone, there weren’t even any old-timers to ask. Had this happened before? Had there ever been somebody like me?

There had to have been.

Werewolves have always been here. Every variation of us, it has to have happened at some point.

Just, it’s the remembering that’s tricky.

Until we knew for sure one way or the other, Libby was packing my head with facts, like trying to scare me back across the line.

Driving here from East Texas, the big Delta 88 eating up the miles, the trunk empty because all our stuff had burned a move or two ago, she’d evened her voice out to sound like a safety pamphlet and recounted all the ways we usually die. It was the werewolf version of The Talk. Just, with more dead bodies.

It took nearly the whole ten hours, no radio, no books, nothing. I stared a hole into the dashboard, not wanting to let her see how perfect all this was. How much I was loving every single wonderful fact.

She’d already told me about the trash.

The rest, though—being a werewolf, it’s a game of Russian roulette, Darren would say. It’s waking up every morning with that gun to your temple. And then he’d snap his teeth over the end of that sentence and give a yip or two, and I’d have to look away so Libby wouldn’t see me smiling, I wanted to be him so bad.

What he was doing those four months we were in New Mexico—the farthest west we’d ever been since splitting east out of Arkansas once and forever—was dragging trailer homes between Portales and Raton, up in Colorado. And if the p-traps of those kitchens and bathrooms were packed with baggies of anything, then he didn’t know about it, anyway.

His logbooks were meticulous, his plates screwed on top and bottom, and his license wasn’t even expired, for once. It wasn’t his name on that license, but, other than that, he was completely legal, right down to the depth of the tread on his tires.

His bosses insisted.

Libby didn’t approve, but you do what you can.

And, up in his truck, the only werewolf death he really had to worry about was that old one of going wolf up in the cab, behind the wheel.

According to Libby, that’s the main way most werewolves cash out. Not always in cab-over rigs on a six-percent grade, the jake brake screaming, but on the road at highway speed, anyway. Usually it’s just making a run to the gas station for ketchup packets. Somebody cuts you off and you wrap your fingers extra tight around the steering wheel, until the tendons in the backs of your fingers start popping into their canine shape. At which point you reach up for the rearview to check yourself, to see if this is really and truly happening. Only, the rearview, it comes off in what’s now your long-fingered paw. And, if the glue’s good, then maybe a piece of the windshield craters out with the mirror, and you know how goddamn much that’s going to cost, and thinking cusswords in your head, that’s no way to hold back the transformation.

Give it a mile, you tell yourself. Just another mile to reel things back in. No, there’s no way to unsplit your favorite shirt, to save the tatters your pants already are. But you’re not going to wreck another motherf—

But you are, you just did. Scraping the passenger side along a guardrail, for the simple reason that steering wheels aren’t designed for monsters that aren’t supposed to exist. You can hardly grip on to it, much less the gear stick, and the shoe your foot’s burst through now, great, it’s wrapped in the gas pedal in some way you couldn’t make happen again in a thousand tries.

This is the time that matters, though. Heading down the road at eighty, now ninety, not really in control, having to hang your new head out the window like a joke, just to see, because the windshield’s all shattered white from you punching it, and, though you run out of gas every time you go anywhere, now the tank’s sloshing full, of course.

It’s only a matter of miles until the semi crests at the other end of the road. The one with your name engraved on the bumper you know is your headstone. Or maybe it’ll be a long drop off the road, into some culvert you’ll never walk up from, werewolf or not. Even just a telephone pole.

Werewolves, we’re tough, yeah, we’re made for fighting, made for hunting, can kill all night long and then some. But cars, cars are four thousand pounds of jagged metal, and, pushing a hundred miles per hour now, the world a blur of regret—there’s only one result, really.

And, if a bad-luck cop sees you slide past the billboard he’s hiding behind, well, then it’s on, right? If he stops you, you’re going to chew through him in two bites, which, instead of making the problem go away, will just multiply it, on the radio.

So you run.

It’s the main thing werewolves are made for. It’s what we do best of all.

Every time I see a chase like that happening on the news, I always say a little prayer inside.

It’s just that one word: run.

And then I turn around, leave that part of the store because I want that chase to go on forever. I don’t want to have to know how it ends.

Another one of us dead.

Another mangled body in a tangle of metal and glass. Just a man, a woman, two legs two arms, because in death the body relaxes back to human bit by bit. In death, the wolf hides.

But cars and highways aren’t the only ways we go. The modern world, it’s custom-designed to kill werewolves.

There’s french fries, for one.

The idea, Libby said, switching hands on the Delta 88’s thin steering wheel and staring straight ahead, boring holes into the night with her eyes, the idea is werewolves think they’ll burn all those calories up the next time they shift. And they’re not wrong. You burn up your french-fry calories and more. But calories aren’t the dangerous part of the french fry. The dangerous part of the french fry is that once you have a taste for them, then, running around in a pasture one night, chasing wild boar or digging up rabbits or whatever—all honest work—you’ll catch that salty scent on the air. If you still had your human mind, you’d know not to chase that scent down. You’d know better.

You’re not thinking like that, though.

You run like smoke through the trees, over the fences, and, when you find those french fries, they’re usually on a picnic table in some deserted place. Which is the dream, right?

Except for the couple sitting on opposite sides of that picnic table. They can be young and broke, having had to dig into couches for enough change for this weekly basket of fries to split out at their favorite place, or they can be the fifty-year-anniversary set, indulging themselves on exactly the kind of greasy fat they’re under strict orders to stay away from.

What they should really stay away from, it turns out, it’s eating those french fries out in the open.

They don’t know they live in a world with werewolves. And by the time they do know, it’s too late.

Blind with hunger, you barrel up onto that table and snatch the fries in a single motion, have eaten them bag and all by the time that picnic table’s two leaping bounds behind you. At which point you register that distinct flavor of salt on this couple’s fingertips as well. Around their lips.

Your paws skid in the gravel, the dust under that gravel rising in a plume you’re about to rip open, explode back through.

The newspaper the next day won’t show crime-scene photos of the remains, or the blood-splashed picnic table.

You won’t need them. You’ll have those photographs in your head already, in those kind of visual flashes Darren says you get in the daytime, like half-remembered dreams.

And you’ll think french fries.

And the next time you follow that salty scent in from the pasture, an honest rabbit dangling limp from either side of your jaws, that two-lane highway you have to cross to get to that tanginess, maybe this time there’ll be a semi hurtling down the near lane, its grille guard thick and purposeful. Or there’ll be men on the roof of the cinderblock bathroom, their scoped rifles waiting, obituaries folded in their tall leather wallets.

They’ll shoot you like they always do, and you’ll run off like werewolves always have, but, like with wrecks at a hundred miles per hour, there’s only so much the wolf can do to knit itself back together. At least when you’re made mostly of french fries.

Maybe your human body turns up two years later in a drainage ditch, mushroomed lead slugs pushed out all around it, but the rest of that body will have been starved down to the bone—coming back from gunshots takes a lot of calories, and you can’t hunt when you’re laid up like that—or maybe the buzzards got there first, for the eyes, the soft parts, until you turn up as another drifter, another vagrant, another tragedy. Unlabeled remains.

Werewolves, we didn’t come up eating french fries through the ages.

It’s taking some time to adapt.

Maybe more time than we’ve got, even.

We’re not stupid, though.

We know to stay mostly to the south and the east. I mean, we’re made for snow, you can tell just by looking at us, we’re more at home in the snow and the mountains than anywhere, but in snow you leave tracks, and those tracks always lead back to your front door, and that only ever ends with the villagers mobbing up with their pitchforks and torches.

That’s one of Darren’s favorite ways to say it: pitchforks and torches.

Like what we’re in here, it’s a Frankenstein movie.

Frankenstein didn’t have to worry about Lycra, though. Or spandex.

Stretch pants are just as dangerous to werewolves as highways.

Libby’s always careful to wear denim, and Darren wouldn’t be caught dead in anything but jeans.

Me either.

The good thing about jeans, it’s that they rip away. Not at the seams like you’d think—that yellow thread there is tough like fishing line—but in the center of the denim, where it’s worn the thinnest. It sucks always having to buy new jeans, or finding ones at the salvage store with long enough legs, but that’s just part of being a werewolf.

A pair of tights, though, man.

Panty hose are murder.

Libby’d only heard about this, never seen it, but supposedly what can happen is you’ve wriggled into a pair of hose or tights—except for color, I really don’t understand the difference between the two—and then, over the course of the day, they’re such a constant annoyance that you kind of forget them altogether.

Enter night, then.

Begin the transformation.

Where pants will tear away, split over the thigh and calf, burst at the waist no matter how double-riveted they are, your fancy panty hose, your stretch pants, they wolf out with you. I’d imagine you look kind of stupid, with your legs all sheer and shiny, but anybody who laughs, you just rip their throat out, feast on their heart. Problem solved.

At least until morning, when you shift back.

Just like that tick that impacted itself into Grandpa’s skin, a pair of panty hose, they’ll retract with your legs. Except, instead of one tick embedding itself in your skin, flaring into some infection, this time every hair is pulling something back in with it.

What happens is your skin, your human skin, it’s part panty hose now. Like the hose have melted onto you, but deeper than deep. And, because you just used all your calories shifting back—it’s not easy like on television—and because you’re hurt, now, you probably can’t go back to wolf yet, can’t get tough enough to sustain this kind of all-over injury.

Worse, this isn’t an immediate death.

You linger through the day.

If your family—your werewolf family—if they really love you, they’ll end it for you. If you’re alone, then it’s hours of trying to pull those panty hose up from your bloody skin. It’s fine, slippery threads of that hose ducking into your veins and getting pumped higher, into your body.

If you’re lucky, one of those clumps makes its way to your brain.

If you’re not lucky, then you end up trying to use your human teeth to peel up all the skin from the top of your thigh, the back of your calf. Wherever you can reach.

It doesn’t help.

I don’t know what the coroner calls these kind of deaths. Probably drug psychosis. Obvious enough to him that a blood test isn’t even necessary. Look at this trailer, this living room, how they were living. Look at how she was picking at her skin. Bag her up, team. And drop a match on your way out.

But there’s another way to die too.

The oldest way, maybe.

Darren had been gone five weeks without checking in, long enough that Libby’d started calling the DPS, asking about wrecks, when his rig rumbled up, shaking every window in the trailer.

She ran out in her apron and hugged him hard around the neck almost before he’d even stepped down from the truck, hugged him hard enough that her feet weren’t even on the ground. Hard enough that I remembered that they’d been pups together. That they’re all that’s left of their litter. Of their family.

Except for me.

It’s why Libby was trying so hard to save me, I think. Like, if I never went wolf, she’d be keeping some promise to my mom. Like she’d have saved one of us.

I’m not sure I wanted to be saved.

I stood there in the doorway, too grown-up for hugs, too young not to have been drawn to the sound of a big rig, and Darren lifted his chin to me, pulled me out into the driveway with him. He had a box of frozen steaks in the sleeper. We were going to eat like kings, he said, messing my hair up and pushing me away at the same time.

All those movies, where the werewolves eat their meat raw? Libby at least seared our steaks on the outside. I didn’t have a taste for it yet, but I could pretend. Darren cued into how long I was having to chew and planted a bottle of ketchup right by my plate, and nobody said anything.

Each veiny, raw bite swelled and swelled in my mouth, but I swallowed them down hard. Because I’m a werewolf. Because I’m part of this family.

After dinner, after Libby’d gone in to work the counter at the truck stop, Darren pulled out the next way to die but, before showing it to me, made me promise I wasn’t a cop, a narc, or a reporter.

“I tell you if I was?” I said to him.

“You report back to Lib about this, it’s both our asses,” he said, then added, “But mostly yours.”

I flipped him off at close range.

He guided my arm to the side, opened the fingers of his other hand one by one and dramatic.

On his palm was a throwing star, like I’d seen at ten thousand flea markets.

Only this one, Darren said, it was silver.

That’s a word werewolves kind of hiss out, like the worst secret.

Every time he spun it up in the air, reaching in to pinch it on both sides and stop its spinning, it was in slow motion for me.

Not just the points were sharp either. Somebody’d ground the edges down, then used a small, patient whetstone on them. Just the weight of this star, it was enough to pull those razor edges down the middle of Libby’s magazine pages. We’d taken turns doing it, just to prove that something so small could be so dangerous, so deadly, so wrong.

When we were done Darren passed it to me reverently, holding it sideways. With a knife, you usually hold the blade yourself, offer the handle like’s polite. There was no safe part of this throwing star, though.

Even the slightest nick and our blood would be boiling.

Darren being careful with it when he handed it across, watching my eyes to make sure I understood what we were playing with here—my heart swelled, my throat lumped up, and I wondered if this is what it feels like, changing.

He was only telling me to be careful because this was dangerous to me as well.

I was part of this family. I was in this blood.

So he wouldn’t see the change happening to my eyes, I tilted my head back, gathered up the trash, and walked the eighty-nine steps to the burn barrels.

The trash was all bloody cardboard from the steaks and fluttering pages from Libby’s magazines we’d cut all to hell.

When I heard the thunk from inside, I knew what was happening. Darren thought he was a ninja. He always had. The first of the new breed, deadlier than either a werewolf or a ninja. He was diving across the living room, falling in slow motion through the movie playing in his head. Diving and, midfall, flinging his throwing star at the paneling of the walls.

With a throwing star, you can’t miss. It’s all edges.

I scratched a flame from my book of my matches, held it to the celebrity gossip magazines Libby would never admit to, and stood there in the first tendrils of smoke, watching my uncle’s blurry silhouette against the curtains.

I watched him finally stop, jerk the index finger of his right hand to his mouth, to suck on it.

I turned back to the fire and held my palms out, waiting for the heat, and I remembered what I saw on a nature show once: that dogs’ eyes can water, sure, but they can’t cry. They’re not built for it.

Neither are werewolves.