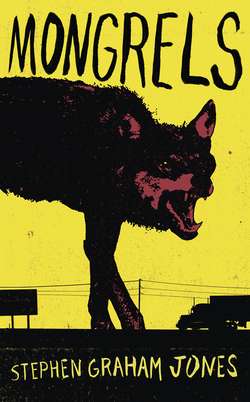

Читать книгу Mongrels - Stephen Jones Graham, Стивен Джонс, Стивен Грэм Джонс - Страница 7

CHAPTER 1 The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress

ОглавлениеMy grandfather used to tell me he was a werewolf.

He’d rope my aunt Libby and uncle Darren in, try to get them to nod about him twenty years ago, halfway up a windmill, slashing at the rain with his claws. Him dropping down to all fours to race the train on the downhill out of Booneville, and beating it. Him running ahead of a countryside full of Arkansas villagers, a live chicken flapping between his jaws, his eyes wet with the thrill of it all. The moon was always full in his stories, and right behind him like a spotlight.

I could tell it made Libby kind of sick.

Darren, his rangy mouth would thin out in a kind of grin he didn’t really want to give, especially when Grandpa would lurch across the living room, acting out how he used to deal with sheep when he got them bunched up against a fence. Sheep are the weakness of all werewolves, he’d say, and then he’d play both parts, growling like a wolf, his shoulders pulled up high, and turning around to bleat in wide-eyed fear, like a sheep.

Libby would usually leave before Grandpa tore into the flock, the sheep screaming, his mouth open wide and hungry as any wolf, his yellow teeth dull in the firelight.

Darren would just shake his head, work another strawberry wine cooler up from beside his chair.

Me, I was right at the edge of being eight years old, my mom dead since the day I was born, no dad anybody would talk about. Libby had been my mom’s twin, once upon a time. She told me not to call her “Mom,” but I did, in secret. Her job that fall was sewing fifty-pound bags of seed shut. After work the skin around her eyes would be clean from the goggles she wore but crusted white with sweat. Darren said she looked like a backward raccoon. She’d lift her top lip over her teeth at him in reply, and he’d keep to his side of the kitchen table.

Darren was the male version of my mom and Libby—they’d been triplets, a real litter, according to Grandpa. Darren had just found his way back to Arkansas that year. He was twenty-two, had been gone six magical years. Like Grandpa said happened with all guys in our family, Darren had gone lone wolf at sixteen, had the scars and blurry tattoos to prove it. He wore them like the badges they were. They meant he was a survivor.

I was more interested in the other part.

“Why sixteen?” I asked him, after Grandpa had nodded off in his chair by the hearth.

Because I knew sixteen was two of eight, and I was almost to eight, that meant I was nearly halfway to leaving. But I didn’t want to have to leave like Darren had. Thinking about it left a hollow feeling in my stomach. All I’d ever known was Grandpa’s house.

Darren tipped his bottle back about my question, looked over to the kitchen to see if Libby was listening, and said, “Right around sixteen, your teeth get too sharp for the teat, little man. Simple as that.”

He was talking about how I clung to Libby’s leg whenever things got loud. I had to, though. Because of Red. The reason Darren had come in off the road—driving truck mostly—was Libby’s true-love ex-husband, Red. Grandpa was too old by then to stand between her and Red, but Darren, he was just the right age, had just the right smile.

The long white scar under his neck, he told me, leaning back to trace his middle finger down its smoothness, that was Red. And the one under his ribs on the left, that cut through his mermaid girlfriend? That had been Red too.

“Some people just aren’t fit for human company,” Darren said, letting his shirt go, reaching down to two-finger another bottle up by the neck.

“And some people just don’t want it,” Grandpa growled from his chair, a sharp smile of his own coming up one side of his mouth.

Darren hissed, hadn’t known the old man was awake.

He twisted the cap off his wine cooler, snapped it perfectly across the living room, out the slit in the screen door that was always birthing flies and wasps.

“So we’re talking scars?” Grandpa said, leaning up from his rocking chair, his good eye glittering.

“I don’t want to go around and around the house with you, old man,” Darren said. “Not today.”

This was what Darren always said anytime Grandpa got wound up, started remembering out loud. But he would go around and around the house with Grandpa. Every time, he would.

Me too.

“This is when you’re a werewolf,” I said for Grandpa.

“Got your listening ears on there, little pup?” he said back, reaching down to pick me up by the nape, rub the side of my face against the white stubble on his jaw. I slithered and laughed.

“Werewolves never need razors,” Grandpa said, setting me down. “Tell him why, son.”

“Your story,” Darren said back.

“It’s because,” Grandpa said, rubbing at his jaw, “it’s because when you change back to like we are now, it’s always like you just shaved. Even if you had a full-on mountain-man beard the day before.” He made a show of taking in Darren’s smooth jawline then, got me to look too. “Babyface. That’s what you always call a werewolf who was out getting in six different kinds of trouble the night before. That’s how you know what they’ve been doing. That’s how you pick those ones out of a room.”

Darren just stared at Grandpa about this.

Grandpa smiled like his point had been made, and I couldn’t help it, had to ask: “But—but you’re a werewolf, right?”

He rasped his fingers on his stubble, said, “Good ear, good ear. Get to be my age, though, wolfing out would be a death sentence now, wouldn’t it?”

“Your age,” Darren said.

It made Grandpa cut his eyes back to him again. But Darren was the first to look away.

“You want to talk about scars,” Grandpa said down to me then, and peeled the left sleeve of his shirt up higher and higher, rolling it until it was strangling his skinny arm. “See it?” he said, turning his arm over.

I stood, leaned over to look.

“Touch it,” he said.

I did. It was a smooth, pale little divot of skin as big around as the tip of my finger.

“You got shot?” I said, with my whole body.

Darren tried to hide his laugh but shook his head no, rolled his hand for Grandpa to go on.

“Your uncle’s too hardheaded to remember,” Grandpa said, to me. “Your aunt, though, she knows.”

And my mom, I said inside, like always. Whatever went for Libby when she’d been a girl, it went for my mom.

It was how I kept her alive.

“It’s not a bullet hole,” Grandpa said, working the sleeve of his shirt down. “A bullet in the front leg’s like a bee sting to a real werewolf. This, this was worse.”

“Worse?” I said.

“Lyme disease?” Darren said.

Grandpa didn’t even look across the room for this. “Diseases can’t touch you when you’re wolfed out either,” he said down to me. “Your blood, it’s too hot for the flu, the measles, smallpox, cancer.”

“Lead poisoning?” Darren asked, in a leading-him-on voice.

“When you change back, the wolf squeezes all that lead back out,” Grandpa said, no humor to it anymore. “Unless it’s in the bone. Then it kind of works around it, like a pearl.”

Darren shrugged a truce, settled back to listen.

“What, then?” I said, because somebody had to.

“A tick,” Grandpa said, pinching his fingers out to show how small a tick is. How little it should matter.

“A tick?” I said.

“A tick,” Darren said.

“It probably came from this fat doe I’d pulled down the night before,” Grandpa said. “That tick jumped ship, went to where the beating heart was.”

“And then when he shifted back,” Libby said, standing all at once by the kitchen table, my faded blue backpack in her hand so she could drop me off at school on her way to work, “when he shifted back, when the werewolf hair went back into his skin to wrap around his bones or wherever it goes, it pulled the tick in with it, right?”

“You do remember,” Grandpa said, leaning back.

“Like trying to climb a flagpole that’s sinking,” Darren said, probably reciting the story from last time Grandpa had told it. He did his bored hands up and up the idea of a flagpole to show, the bottle cocked in his fingers not even spilling.

“The word for it is ‘impacted,’” Libby said right to me. “It’s when something’s most of the way into the skin. A splinter, a tooth in your mouth—”

“A tick,” Grandpa cut in. “And I couldn’t reach it. That was the thing. I couldn’t even see it. And your grandma, she knew that the fat ones like that are full of babies. She said if she grabbed it with the needle-noses, popped it, the babies would all go in my blood, and then they’d be like watermelon seeds in my stomach.”

“That’s not how it works,” Libby said to me.

“So you went to the doctor,” Darren said over her. “In town.”

“Doc, he heated up the end of a coat hanger with his lighter,” Grandpa said to me, trying to be the one to tell the story right, “and he—” He acted it out, stabbing the burning-hot bent-out coat hanger down and working it around like stirring a tiny cauldron. “Why there’s a scar there now, it’s that I wouldn’t let him dress it, or stitch it. You know why, don’t you?”

I looked from Libby to Darren.

They each directed me back to Grandpa. It was his story, after all.

“Because you’ve got to be born to the blood to take it,” Grandpa said, his voice nearly at a whisper. “If that doctor had got even one drop into a cuticle, he’d have turned into a moondog, sure as shooting.”

My heart was thumping. This was better than any bullet hole.

Libby was making lifting motions with her hand for me to get up already, that she was going to be late, she was going to get fired again.

I stood from this dream, still watching Grandpa.

“Let him finish,” Darren said to Libby.

“We don’t have—”

“If you’re bit, or if you get the blood in you,” Grandpa said anyway, “then it burns you up fast, little pup, and it hurts. All you can do is feel sorry. Those ones, they just have these wolf heads, a man body. They never understand what’s happening to them, just run around slobbering and biting, trying to escape their own skin, sometimes even chewing their own hands and feet off to stop them hurting.”

He wasn’t looking at me anymore, but out the window. The eye I could see on my side, it was his cloudy one.

I think it was the one he was looking with.

Neither Libby nor Darren said anything, but Libby did accidentally look out the window, like just for a peek. Just to be sure.

Then she set her mouth into a grim line, pulled her face back to the living room.

I was going to be late for school and it didn’t matter.

“Come on,” she said, taking my hand, and on the way past Grandpa I brushed my hand on the sleeve of his shirt, like to tell him it was okay, I think. That it was a good story. That I’d liked it. That he could keep telling me these stories forever, if he wanted. I would always listen. I would always believe.

He flinched away from my hand, looked around for where he was.

“Here, old man,” Darren said, handing a strawberry wine cooler across to him, and I climbed into my side of Libby’s El Camino, the one she had from finally breaking up with Red, and halfway to school I started crying, and I couldn’t figure out why.

Libby switched hands on the wheel, pulled me over to her.

“Don’t think about it,” she said. “I don’t even know how he really got that scar. It was before we were all born.”

“Because Grandma was there,” I said.

Just like my mom, Grandma had died the day she gave birth. It was like a curse in our family.

“Because Grandma was there,” Libby said. “Next time he tells that stupid story, the tick won’t even be on the back of his arm anymore. It’ll have been that old cut up on his eyebrow, and the doctor heated his pocketknife up, not a coat hanger. One time when he told it to us it was that one scar that pulls beside his mouth.”

This is the way werewolf stories go.

Never any proof. Just a story that keeps changing, like it’s twisting back on itself, biting its own stomach to chew the poison out.

The next week we found Grandpa out in the pasture without any clothes. His knees were bloody, not scabbing over yet, and the heels of his hands were scraped raw, and his fingertips were chewed by the gravel and the thorns. He was staring at us but he wasn’t seeing us, even with his good eye.

Darren and me got to him first. I was riding on Darren’s back. He was running everywhere at once, and there were tears coming back on the side of his face.

He let me down slow when we saw Grandpa.

“He’s not dead,” I said, to make it true.

It worked.

Grandpa’s back lifted and fell with his next wheezy breath.

Darren took two steps away and slung his bottle out as hard as he could, the pale pink liquid tracing drippy circles for the first few feet, then nothing. Just a smell on the air like medicine.

“How old you think he is?” Darren said to me.

I looked up to him, down to Grandpa.

“Fifty-five,” Darren said. “This is what happens.”

Libby heard his bottle break into whatever it broke into, and traced it back to us. She ran over, her hands in a steeple over her mouth.

“He thinks he’s shifted,” Darren told her, disgusted.

“Help me!” Libby said, falling to her knees by her dad, trying to get his head into her lap, her long black hair shrouded over both of them.

That was one day.

I quit going to school for that week, and promised myself to keep Grandpa alive.

The way I did it was with stories. By keeping him talking.

“Tell me about Grandma,” I said one night after Darren had left, after Red had come and stood at the gate like a statue until Libby drifted out to him. She couldn’t help it.

I was asking about Grandma because if he thought he was really shifting into a werewolf, then talking to him about it wasn’t going to make him any better.

“‘Grandma,’” he said in his new halfway slur, then shook his head no, said, “she never ever got to be called ‘Momma,’ did she?”

I wanted to take my question back. To start over.

Grandpa breathed a deep important breath in, then out. He said, “You know werewolves, they mate for life, right? Like swans and gophers.”

He pretty much only sat in his chair now. Used to when he smiled one side of his mouth, it meant something good was coming. Now it meant something bad had happened, Libby said.

“Gophers?” I said.

“You can smell it on them,” he said, snuffling his nose to show.

I’d never seen a gopher. Just the mounds.

“Grandma,” Grandpa said then, clearer. “You know when she first figured me out, what I was, she thought it meant I was married to the moon, like. That that was the only time I would go out howling.”

I narrowed my eyes and he caught it, added, “That’s not how it works, little pup. Too short a leash. We’d starve like that. Anyway. I was married to her, wasn’t I?”

A log in the fire popped sparks up the chimney. Darren called it an old-man fire. It was September.

“Another thing about werewolves,” Grandpa said at last. “We age like dogs. You should know that too.”

“Like dogs,” I repeated.

“You can burn up your whole life early if you’re not careful. If you spend too much time out in the trees, running your dinner down.”

I nodded. As long as he was talking, he wasn’t dead.

“Grandma,” I said again, because that’s where we’d been, before the werewolves.

Grandpa swallowed a lump, coughed it back up and spit it in his hand, rubbed it into the blanket on his lap.

“There used to be a secret,” he said. “A way for them, for the wives, for them not to …”

Not to die, I knew. Since Grandpa’d started living mostly in the living room, he’d decided to solve the family curse. It was what all the stolen library books by the couch were for. So he could find the old way for a human woman to live with a werewolf and not die from giving birth.

His research was the big reason Libby stayed mostly in the kitchen. She said nothing he did was going to bring her mom back, was it? There wasn’t any big werewolf secret. Grandma had just died, end of story.

Darren thought Grandpa’s books were funny. They were all strange stories, amazing facts.

“We buried her in the church graveyard,” Grandpa said then, on some different part of the Grandma-story running in his head. “And they—they dug her up, little pup. They dug her up and they—they—”

Instead of finishing, he lurched forward so I had to push back to keep him from spilling out of his chair. I didn’t know if I could get him back into it.

By the time he looked up, he’d forgot what he’d been saying.

He’d told it to me before, though, when Libby wasn’t around to stop him.

It was another werewolf story.

After Grandma had died giving birth, a rival pack had dug her up as a message to him. It was about territory.

Grandpa had taken the message back to them on the end of a shovel, and then used that shovel on them.

This had all been his territory back then, he usually said, to end that story out. His territory as far as he could see, as much as he could fight for. Some days he’d claim all of Arkansas as his, even, ever since the war had spit him up here.

But I wasn’t stupid. I wasn’t at school that month, but I was still learning. Libby had finally told me that the scar on Grandpa’s arm, it was probably from a cigarette he’d rolled over on once. Or an old chickenpox. Or a piece of slag melting into his sleeve, burning down into his skin.

What I had to do to get to the truth of the story was build it up again from the same facts, but with different muscle.

Grandma had died and been buried. I knew that. Even Libby said it.

Probably what had happened—no, what had to have happened, the worst that could have happened—was that some town dogs had got into the cemetery the night after the funeral, when the dirt was still soft. And then Grandpa had gone after that pack with his rifle, or his truck, even if it had taken all month. And then used his shovel to bury them.

I preferred the werewolf version.

In that one, there’s Grandpa as a young man, a werewolf in his prime. But he’s also a grieving husband, a new and terrified father. And now he’s ducking out the doorway of the house this other pack dens up at. And his arms, they’re red and steaming up to the shoulders, with revenge.

If Libby grew up hearing that story, if he told it to her before she was old enough to see through it to the truth, then all she would remember would be the hero. This tall, violent, bloody man, his chest rising and falling, his eyes casting around for the next thing to tear into.

Ten years later, of course she falls for Red.

Everything makes sense if you look at it long enough.

Except Darren showing up at the house two or three hours later. He was naked, was breathing hard, covered in sweat, his eyes wild, leaves and sticks in his hair, one shoulder raw.

Slung over his shoulder was a black trash bag.

“Always use a black bag,” he said to me, walking in, dropping the bag hard onto the table.

“Because white shows up at night,” I said back to him, like the three other times he’d already come back naked and dirty.

He scruffed my hair, walked deeper into the house, for pants.

I peeled up the mouth of the bag, looked in.

It was all loose cash and strawberry wine coolers.

The last story Grandpa told me, it was about the dent in his shin.

Libby leaned back from the kitchen sink when she heard him starting in on it.

She was holding a big raw steak from the store to her face. It was because of Red, because of last night.

When she’d come in to get ready for work, she’d seen Darren’s trash bag on the table, hauled it up without even looking inside. She strode right back to Darren’s old bedroom. He was asleep on top of the covers, in his pants.

She threw the bag down onto him hard enough that two of the wine-cooler bottles broke, spilled down onto his back.

He came up spinning and spitting, his mouth open, teeth bared.

And then he saw his sister’s face. Her eye.

“I’m going to fucking kill him this time,” he said, stepping off the bed, his hands opening and closing where they hung by his legs, but Libby was already there, pushing him hard in the chest, her feet set.

When the screaming and the throwing things started, one of them slammed the door shut so I wouldn’t have to see.

In the living room, Grandpa was coughing.

I went to him, propped him back up in his chair, and, because Libby had said it would work, I asked him to tell me about the scar by his mouth, about how he got it.

His head when he finally looked up to me was loose on his neck, and his good eye was going cloudy.

“Grandpa, Grandpa,” I said, shaking him.

My whole life I’d known him. He’d acted out a hundred werewolf stories for me there in the living room, had once even broke the coffee table when an evil Clydesdale horse reared up in front of him and he had to fall back, his eyes twice as wide as any eyes I’d ever seen.

In the back of the house something glass broke, something wood splintered, and there was a scream so loud I couldn’t even tell if it was from Darren or Libby, or if it was even human.

“They love each other too much,” Grandpa said. “Libby and her—and that—”

“Red,” I said, trying to make it turn down at the end like when Darren said it.

“Red,” Grandpa said back, like he’d been going to get there himself.

He thought it was Red and Libby back there. He didn’t know what month it was anymore.

“He’s not a bad wolf either,” he went on, shaking his head side to side. “That’s the thing. But a good wolf isn’t always a good man. Remember that.”

It made me wonder about the other way around, if a good man meant a bad wolf. And if that was better or worse.

“She doesn’t know it,” Grandpa said, “but she looks like her mother.”

“Tell me,” I said.

For once he did, or started to. But his descriptions of Grandma kept wandering away from her, would strand him talking about how her hands looked around a cigarette when she had to turn away from the wind. How some of her hair was always falling down by her face. A freckle on the top of her left collarbone.

Soon I realized Darren and Libby were there, listening.

It was my grandma, but it was their mom. The one they’d never seen. The one there weren’t any pictures of.

Grandpa smiled for the audience, for his family being there, I think, and he went on about her pot roasts then, about how he would steal carrots and potatoes for her all over Logan County, carry them home in his mouth, shotguns always firing into the air behind him, the sky forever full of lead, always raining pellets so that when he shook on the porch after getting home, it sounded like a hailstorm.

Libby cracked the refrigerator open, pulled out a steak, held it under the water in the sink so it wouldn’t stick to her face.

Darren eased into the living room, sat on his haunches on the floor past the chair he usually claimed, like he didn’t want to break this spell, and Grandpa went on about Grandma, about the first time he saw her. She was in a parade right over in Boonesville, had a pale yellow umbrella over her shoulder. It didn’t look like a huge daisy, he said. Just an umbrella, but in the clear daytime.

Darren smiled.

His face on the left side had four deep scratches in it now, but he didn’t care. He was like Grandpa, was going to have a thousand stories.

In the kitchen Libby finally turned the water off, pressed the steak up to her left eye. It wasn’t swelled all the way shut yet. Her eyeball was shot red like it had popped.

I hated Red at least as much as Darren did.

“Go on,” Darren said to Grandpa, and for two or three more minutes we went around and around the house with him, after Grandma. Until Grandpa leaned forward to pull up the right leg of his pants. Except he was just wearing boxers. But his fingers still worked at the memory of pants.

“He wanted to hear about how this happened,” he said, and tapped his finger into a deep dent on his shin I’d never noticed before.

This was when Libby pushed up from the sink.

Her lips were red now too, and part of me registered that it was from the steak. That she’d been chewing on it.

The rest of me was watching Grandpa’s index finger tap into his shin. Because I’d asked about the scar by his mouth, not one on his leg. But I wasn’t going to mess this up.

“Used to have this dog …” he said to me, just to me, and Libby dropped her steak splat onto the linoleum.

“Dad,” she said, but Darren held his hand up hard to her. “He can’t, not this—” she said, her voice getting shrieky, but Darren nodded yes, he could.

“You weren’t there,” she said to him, and when Darren looked over to her again she spun away with a grunt, crashed out the screen door, and I guess she just kept running out into the trees. The El Camino didn’t fire up, anyway.

“What happened?” I said to Grandpa.

“We had this dog,” Grandpa said, nodding like it was all coming back to him now, moving his fingers up by his eyes like the story was filaments in the air, and if he held his hand just right he could collect enough of them to make sense, “we had this dog and he—he got tangled up with something, got bit, got bit and I had to, well.”

“Rabies,” I filled in. I knew it from the kid in class who’d had to get the shots in his stomach.

“I didn’t want to wake your sister,” Grandpa said across to Darren. “So I—so I used a ball-peen hammer instead, right? A hammer’s quiet enough. A hammer’ll work. I dragged her out by the fence on that side, and—” He was laughing now, his wheezy old man’s laugh, and fighting to stand, to act this out.

“Her?” I said, but he was already acting it out, was already holding that big rangy dog by the collar, and swiping down at it with the hammer, the dog spinning him around, his swings missing, one of them finally cracking deep into his own shin so he had to hop on one leg, the dog still pulling, trying to live.

He was laughing, or trying to.

Darren was leaning his head back, like trying to balance his eyes back in.

“I like, I like to—” Grandpa said, finding his chair again, collapsing into it, “once I hit her that first time, little pup, I like to have never got that next lick in,” which was the punch line.

He was the only one laughing, though.

And it wasn’t really laughing.

The next Monday Libby took me back to first grade, sat there at the curb until I’d stepped through the front doors.

It lasted two days.

When we came back from school and work Tuesday, Grandpa was half out the front door, his cloudy eyes open, flies and wasps buzzing in and out of his mouth.

“Don’t—” Libby said, trying to snag my shirt, keep me in the El Camino.

I was too fast. I was running across the caliche. My face was already so hot.

And then I stopped, had to step back.

Grandpa wasn’t just half in and half out of the door from the kitchen. He was also halfway between man and wolf.

From the waist up, for the part that had made it through the door, he was the same. But his legs, still on the kitchen linoleum, they were straggle-haired and shaped wrong, muscled different. The feet had stretched out twice as long, until the heel became the backward knee of a dog. The thigh was bulging forward.

He really was what he’d always said.

I didn’t know how to hold my face.

“He was going for the trees,” Libby said, looking there.

I did too.

When Darren walked up from wherever he’d been, he was still buttoning his shirt. It was so it wouldn’t be sweaty when he got wherever he was going, he’d told me.

I’d believed him too.

Used to, I believed everything.

He stopped when he saw us sitting on the El Camino’s tailgate.

We were splitting the lunch I hadn’t eaten at school, since the teacher had sneaked me some pepperoni slices from a plastic baggie.

“No,” Darren said, lifting his face to the wind. It wasn’t for my half of the bologna sandwich. It was for Grandpa. “No, no no no!” he screamed now, because he was like me, he could insist, he could make it true if he was loud enough, if he meant it all the way.

Instead of coming any closer, he turned, his shirt floating to the ground behind him.

I stepped down to go after him but Libby had me by the shoulder.

Because we couldn’t go inside—Grandpa was in the doorway—we sat in the bed of the El Camino, Libby’s fingernails picking at the edge of the white stripes that came up the tailgate. There was faded black underneath them, like the rest of the car. When night cooled the air down we retreated to the cab, rolled the windows up so that soon we were breathing in the taste of Red’s cigarettes. I pushed the pad of my index finger into a burn on the dashboard, then traced a crack in the windshield until it cut me.

I was asleep by the time the ground shook underneath us.

I sat up, looked through the rear window. The trees were glowing.

Libby pulled my head close to her.

It was Darren. He’d stolen a front-end loader.

“Your uncle,” Libby said, and we stepped out.

Darren pulled the front-end loader right up to the house, lowered the bucket to the doorway, and then he swung down, stepped around, lifted Grandpa into the bucket, Grandpa’s mouth hanging open, his legs shaped more like they had been. His mouth was still trying to push forward, though. Into a muzzle.

“He was too old to shift,” Libby said to me, shaking her head at the tragedy of it all.

“But what if he’d made it?” I said.

“You’re not going to be stupid too, are you?” she said, and the way she tried to smile I knew I didn’t have to answer.

Darren couldn’t call to us because the front-end loader was too loud, but he stood on the first step, hung out from the grab bar, waved us over.

“I don’t want to,” Libby said to me.

“I don’t want to either,” I said.

We climbed up with Darren, sat on the swells to either side of his bouncy, ripped-up seat, the glass cold on my left arm.

Darren drove right out into the field and followed it until there was only trees, and then he pushed through the trees back to a creek. He lifted Grandpa out, cradled him down to the tall dry grass, and then he used the bucket to dig out the steep side of the bank.

He picked his dad up in his arms, looked across to Libby, then to me.

“Your grandpa,” he said, holding him right there. “One thing I can say about his old ass. He always liked to run his dinner down instead of getting it at the store, didn’t he?”

He was kind of crying when he said it, so I looked away.

Libby bit her lip, pulled at the hair on the right side of her face. Darren lowered Grandpa into the new hole, and then he used the front-end loader to drag all the dirt back down over him, and he piled more on, finally even digging up the creek and dripping that silt down, then crushing that mound down harder and deeper and madder and madder, breaking all Grandpa’s bones, so it wouldn’t matter if anyone dug them up.

This is the way it is with werewolves.

“What about me?” I said on the way back, in the cab of the front-end loader.

“What do you mean what about you?” Darren said, and when I looked over the moon had just broke over the top of the trees, was bright and round. It outlined him perfect, the way he leaned over that steering wheel like he’d been born to it.

Every boy who never had a dad, he comes to worship his uncle.

“He means what about him,” Libby said, angling her words at Darren in a different way.

“Oh, oh,” Darren said, throttling up now that we were out of the trees. “Your mom, she—”

“Not all kids born to a werewolf are a werewolf,” Libby said. “Your mom, she didn’t catch it from your grandpa.”

“Some don’t,” Darren said.

“Some are lucky like that,” Libby added.

The rest of the ride was quiet, and the rest of the night too, at least until Darren started sucking air through his teeth at the kitchen table, like he’d been thinking of something the whole time and finally couldn’t keep it in his head even one minute more.

“Don’t,” Libby said to him.

I was sitting with her at the hearth, the fire banked high for as late as it was.

“Don’t wait up,” Darren said, his eyes looking away, and then walked out before Libby could stop him.

I don’t think she would have, though.

The front-end loader fired up, dragged its lights across the kitchen window, and was rumbling back toward town, the bucket lifted high, to look under.

“Pack your things,” Libby said to me.

I used a black trash bag.

When Darren came back in the morning I was standing at the El Camino’s tailgate, looking for my math book.

Werewolves don’t need math, though.

Darren was naked again.

Instead of loose cash and strawberry wine coolers, what he had over his shoulder was a wide black belt.

“Remember when you used to want to be a vampire?” he said down to me, watching the house the whole time.

His hands and chin were black with dried blood, and he smelled like diesel.

I nodded, kind of did remember wanting to be a vampire. It was from a sun-faded old comic book he’d let me read with him when he first got back.

“This is better,” Darren said, his infectious smile ghosting at the corners of his mouth, and then Libby was there, her hands dusted white with flour, her sleeves pushed up past her elbows.

She stopped a few steps out, dabbed a line of white off her face, then looked down the road behind Darren and all the slow way back to him. To his hands. To his chin. To his eyes.

“You didn’t,” she said.

“Wasn’t my fault,” Darren said. “Wrong place, wrong time.”

The creaky black belt hooked over his shoulder was a cop’s. You could tell from all the pouches and pockets. The pearl-handled pistol was even still there in its molded holster, the dull white handle flapping against his side, flashing a silver star with each step.

“Bet we can get seventy-five for it at the truck stop,” he said, hefting it out like to show what it was worth.

“Go inside,” Libby said, pushing me toward the house.

She should have pushed harder.

“This is the end of the liquor stores,” she said to Darren, her voice flat like the back edge of a sharp knife, one she could flip around to the blade in a flash.

“Bears and wolves aren’t meant to get along …” Darren said. The cool way he looked to the left and touched a spot above his eyebrow when he said it, it sounded like a line he’d been saving, his whole long way home.

Libby shoved him hard in the chest.

Darren was ready, but still he had to give a bit.

He tried to sidestep past her, for the house, for clothes, for a wine cooler, but Libby hauled him back, and because I was close enough, I heard one of them growling way down in their chest. A serious growl.

It made me smaller in my own body.

But I couldn’t look away.

Darren’s skin was jumping on his chest now.

It was Grandpa, rising up in his son. What I was seeing was Grandpa as a young man, itching to roam, to fight, to run down his dinner night after night because his knees were going to last forever. Because his teeth would always be strong. Because his skin would never be wax paper. Because fifty-five years old was a lifetime away. Because werewolves, they live forever.

And then the smell came, the smell that’s probably what birth smells like. Like a body turned inside out. A body turning inside out.

“Dad’s dead, Lib,” Darren said, and all his pain, his excuse for whatever had happened in town, it was right there in his voice, it was right there in the way his voice was starting to break over.

“And he’s not,” Libby said, flinging a hand down to me. Darren flashed his eyes over to me, came back to Libby. “We can’t just do whatever we want anymore,” she said, her teeth hardly parting from each other. “Not until—”

I balled my hand into a fist, ready to run, ready to hide. I knew where Grandpa’s creek was.

“Until what?” Darren said.

“Until,” Libby said, saying the rest with her eyes, in some language I couldn’t crack into yet.

Darren stared at her, stared into her, his jaw muscles clenching and flaring now, his pupils either fading to a more yellowy color or catching the morning sun just perfect. Except the sky was still cloudy. Right when he flashed those dangerous new eyes up at Libby, she slapped him hard enough to twist his head around to the side.

Her claws were out too, pushed out not from under her fingernails like I’d been thinking but from the knuckle just above that. I hadn’t even seen it happen.

My eyes took snapshots of every single frame of that arc her hand traced.

A piece of Darren’s lower lip strung off his mouth, clumped down onto his chest. The lower part of his nose sloughed a little lower, cut off from the top half.

His eyes never moved.

By his legs, his fingers stretched out as well, reaching for the wolf.

“No!” Libby yelled, stepping forward, taking him by both shoulders, driving her knee up into his balls hard enough to stand him up on tiptoes.

Darren fell over frontward, curled up there naked and skin-jumpy on the caliche, and Libby stood over him breathing hard, still growling, the canine muscles under her skin writhing in the most beautiful way, her claws glistening black, and what she told him, her tone taking no questions, was that his liquor-store days, they were goddamn over, that he was a truck driver now, did he understand?

“For Jess,” she said at the end of it all—my mother, Jessica, named for her mom—and then wiped at her eyes with the back of her hand, another dab of claw-shiny black showing on her inner forearm for the briefest instant, for not really long enough to matter.

Except it did. To me.

It made the world creak all around us, into a new shape. This moment we were standing in, it was a balloon, inflating.

Inside of ten minutes, we’d have the bed of the El Camino piled with cardboard boxes and trash bags, Grandpa’s house burning down to the cement slab, the three of us stuffed into the cab of the El Camino, to put as much distance between us and this dead cop as we could in a single night.

Now, though.

In this moment where everything went one way, not the other.

Because of that dab of shiny black on my aunt’s inner forearm, I was listening to my grandpa again.

This is one of the first stories he ever told me, right before Darren rolled back into town to keep Red off Libby. His left eye then, it was probably already pressuring up to burst back into his brain.

The story was about dewclaws.

And none of Grandpa’s stories were ever lies. I know that now. They were just true in a different way.

He had been telling me secrets ever since I could sit still enough to listen.

On dogs, he told me, dewclaws, they’re useless, just leftover. From when they were wolves, Grandpa insisted.

Dewclaws, they’re about birthing, they’re about being born.

Just like baby birds need a beak to poke through their shells, or like some baby snakes have a sharp nose to push through their eggshells, so do werewolf pups need dewclaws. It’s because of their human half. Because, while a wolf’s head is custom made for slipsliding down a birth canal, a human head—all pups shift back and forth the whole time they’re being born—a human head is big and blocky by comparison. And the mom’s lady parts, they aren’t made for that. You can cut the pups out like they tried to do for Grandma, but you need somebody who knows what they’re doing. When there’s not a knife, or somebody to hold it, and when the mom’s human, not wolf—that’s the reason for the dewclaws. So the pup can reach through with its paw. So that one flick of sharpness high up on the inside of the forearm can snag, tear the opening a bit wider.

It’s bloody and terrible, but it works. At least for the pup.

And now I understood, about Grandpa’s tick. That smooth divot of scar tissue he’d shown me on the back of his arm.

It was so I would look at my own arms, someday.

On the inside of each of my forearms there are two pale slick scars that Libby’d told me were from the heating element of Grandpa’s stove, when I’d reached in for toast when a piece of bread was still as big as my head.

Grandpa had been telling me the whole time, though: dogs?

I’d seen dogs through the window driving to school, but there’d never been a dog at Grandpa’s place.

Dogs know better. Dogs know when they’re outmatched.

“No,” Libby said, looking across to me, looking at my inner forearms with new eyes, matching my two scars up with her dewclaws.

It wasn’t a dog Grandpa had to drag out by the fence.

I can see it now the way he would have said it, if he could have said it the way it happened.

A fourteen-year-old girl starts to have a baby, a human girl starts to have a human baby, only, partway through it, that baby starts to shift, little needles of teeth poking through the gums months too early. It’s not supposed to happen, it never happens like this, she was the one of the litter born with fingers, not paws, she’s supposed to be safe, is supposed to throw human babies, but the wolf’s in the blood, and it’s fighting its way to the surface.

My mom, I didn’t just tear her open, I infected her.

Werewolves that are born, they’re in control of what they are, or they can come to be, at least. They have a chance.

If you’re bit, though, then it runs wild through you.

“We’re going to go far from here, so far from here,” Libby was saying right into my ear, the rest of me pressed up against her, both of us trembling.

Her breath smelled like meat, like change.

Darren wasn’t there the night it happened, when I was born. But she was.

The real story, the one she saw, the one Grandpa was trying to say out loud finally, it’s that a father carries his oldest daughter out past the house, he carries her out and she’s probably already changing for the first time, into an abomination, but he holds his own wolf back, isn’t going to fight her like that.

This is a job for a man.

He raises the ball-peen hammer once—the rounded head is supposed to be kind—but he isn’t decisive enough, can’t commit to this act with his whole heart, but he has her by the scruff, and she’s on all fours now, is snapping at him, her just-born son screaming on the porch, her twin sister biting those baby-sharp dewclaws off for him once and forever, and for the rest of that night, for the rest of his life, this husband and father and monster is swinging that little ball-peen hammer, trying to connect, his face wet with the effort, the two of them silhouettes against the pale grass, going around and around the house.

We’re werewolves.

This is what we do, this is how we live.

If you want to call it that.