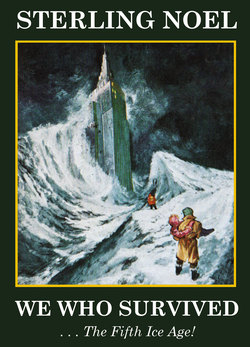

Читать книгу We Who Survived - Sterling Noel - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеI WAS PERMITTED to resign my Commission in the Republic of North America Air Force in 2203 because of the technicality over-age in grade. The fact that I was a Missiles Group Commander would be the real reason. There were no more Missiles Groups. Missiles pilots were as obsolete as automobiles and the missiles jockeys of the New Air Force didn’t get any closer to their vehicles than an electronic control center hundreds of miles away.

So I got a job with Boren Industries in Missouri Center supervising the final assembly of Lopez Rectifiers and I wrote a long letter to Marge Couzins in Portland Complex and told her I was once and for all back on earth and available. I wrote three pages of pledges and when I went out to mail them at the post office, so that she would get my missive the next morning, it had started to snow.

I remarked on the snow, of course. Everybody did. In fact, the whole world had been remarking and complaining and predicting about the weather for several years, and particularly since the spring, which had started with twenty-seven days of drenching rain accompanied by high winds and near-freezing temperatures. There had been a respite of a few weeks, then the rain and cold had resumed and it had remained that way all summer.

By the time September had arrived there was a definitely discernible undercurrent of fear and apprehension wherever and whenever groups of people gathered. There was a feeling of impending disaster, and I believe we were all affected by it.

The Government and innumerable groups of intelligent citizens were doing their utmost to counteract this incipient panic, but they were not gaining noticeable headway. Then the sudden beginning of the mid-September snow and its accompanying cold wave of sub-zero temperatures seemed to put the lid on the pot, and the fury of doom-criers was redoubled.

Much of this pessimism, of course, was not yet in evidence on the Saturday afternoon that I walked through the early snow to the post office.

I had received an urgent summons that morning from Elaine Harrow to have dinner with her and Dr. Gabriel Harrow at their farm at Fallon, across the river in Kansas, and I walked from the post office to the Board of Trade Building, where I got an ML taxi on the roof; I started for Kansas about six o’clock, hoping that I would find a haven from the doom-talk at the safe home of my friends. That was six o’clock on September 14, 2203. Ten minutes later I was at the Harrow’s jet shield. I walked through about three inches of snow to the front door and was admitted by Elaine, dressed in Fincham arctics. Elaine was a small, dark woman in her thirties, but looked most of the time like twenty-four or twenty-five. She could wear slacks—or even Fincham arctics—with more style than a Paris opening. But the highball in her hand rattled its ice as she gestured me into the living room. A frown creased her forehead.

“Come in, Vic, hurry,” she said. “Did you ever see anything like this insane weather?”

I closed the door against the swirling snow and followed her into the huge living room. She went to a sideboard and mixed me a Scotch. “Something worrying you?” I asked.

She turned to me with my drink in her hand and gave me a questioning look. “Did you hear the six o’clock news?” she demanded. “President Gamberelli’s statement?”

“No.”

“The President said there is nothing to fear but fear itself—that we should close our ears to the alarmists who say that we are all about to be engulfed by vast glaciers. He said there is no basis for alarm and he quoted Alex Vidal and Duncan Curran and a couple of others I never heard of. Then, near the end, he mentioned Gabe by name. He said, ‘It is unfortunate that in this hour of alleged peril we have been unable to obtain the reassurance of such men as Dr. Gabriel Harrow and Professor John Wheeler Osborne.’ Then some more tripe about how it was the duty of our great scientists to keep the public informed of the facts and reassured. . . . I’ve never been so angry! What right has he got to criticize Gabe and Jack Osborne in a public broadcast?”

“Where is Gabe?” I asked.

“He’s on his way.”

“Simmer down,” I said. “Why didn’t Gabe and Professor Osborne give Gamberelli a statement?”

“How would I know?” she demanded. “Gabe will tell you when he comes in. But whatever the reason, it doesn’t give that cheap politician the right—”

“Wait a minute,” I interrupted, “we’re getting to the crux of this. Does Gabe support this disaster talk?”

“No—not disaster talk. But he has a sound theory about what is happening, and he isn’t going to back up a lot of wild statements by Gamberelli and the politicians. He’s been with Jack Osborne and Bob Jordan for weeks now at Mt. Hood, and he wouldn’t refuse to reassure the people unless he had a good reason.”

“That figures. Are you sure he’s coming home to dinner tonight?”

“Of course I’m sure. I just talked to him. He’s in a Jupiter one-o-eight over Cheyenne, so he’ll be here in less than a half hour. But that Gamberelli. . . !”