Читать книгу Bodies, Affects, Politics - Steve Pile - Страница 10

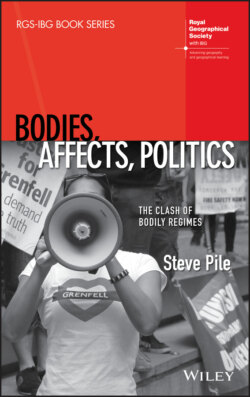

London’s Burning

ОглавлениеBy the 2010s, nearing forty years after the Lancaster West Estate had been completed, Notting Hill was best known for its flamboyant Afro‐Caribbean carnival, a saccharin romantic comedy film, and massive inequality: popstars, super models and politicians lived in multimillion‐pound homes, ordering the latest ‘flat white’ coffees and quaffing Chenin Blanc wine from South Africa, while the new model estates of the 1970s visibly deteriorated. The area had become trendy, with beautiful and exclusive and increasingly expensive private housing sitting side by side with the rundown Lancaster West Estate. In 2012, Westminster Council began an £8.7M renovation of the Grenfell Tower, which received new windows, a new heating system and, on the outside, aluminium cladding was introduced to improve the block’s appearance and rain‐proofing. The renovation was completed four years later in May 2016. A new story of class and race had been set in motion.

At 54 minutes past midnight on 14 June 2017, the emergency services received the first reports of a fire at Grenfell Tower. Starting in a faulty fridge‐freezer on the fourth floor, the fire quickly engulfed the Tower Block. The fire burned for 60 hours, despite the attendance of 70 fire engines and over 250 firefighters. The fire killed 72 people, in 23 of the tower’s flats, mostly above the twentieth floor.

On 21 May 2018, the Grenfell Tower public inquiry began, after completing its procedural hearings in December 2017. (Complete proceedings are available online at grenfelltowerinquiry.org.uk and on YouTube.) It opened with a commemorative hearing, with testimony from the relatives of all the dead. Along with the memories and feelings of the relatives, the inquiry included pictures and videos. There are many stories in the fire – all are heart‐breaking.

Marcio Gomes was in tears as he recalled the excitement that news of his wife’s pregnancy had brought the family. Hours after the fire, he was holding his stillborn child in his arms, while his wife and two daughters lay in a coma having escaped from their twenty‐first floor flat at around 4 in the morning. He told the hearings on its first day: ‘I held my son in my arms that evening, hoping it was all a bad dream, wishing, praying for any kind of miracle…that he would just open his eyes, move, make a sound’. The family had plans for Logan; he was going to be a superstar; he was going to be a football fan, supporting Benfica and Liverpool. Marcio added, ‘He might not be here physically, but he will always be here in our hearts forever […] Our sleeping angel he was. We let him go with the doves so that he can fly with the angels. We are proud of him even though he was only with us for seven months’. Later that day, the West End Final Extra edition of the Evening Standard chose Marcio’s words for its headline: ‘I Held My Son In My Arms Hoping It Was A Bad Dream’, reinforcing this with a picture of Grenfell Tower in flames. This front page replaced the earlier West End Final headline: ‘Grenfell: Don’t Make Us Wait 30 Years for Justice’, which (curiously) had no accompanying pictures of the tragedy.

The change in the headline might, on the surface, seem innocuous for both are highly emotional: one headline speaks to the families’ angry demand for justice, while the other picks up on the families’ unbearable loss. These two stories have the same source – yet, in this moment, the unrelenting anger that inhabits the demand for justice is replaced by the unspeakable grief and horror of the tragedy. Perhaps, maybe, because a story about the tragic loss of a child would have more appeal for the Evening Standard (a free paper that relies on advertising revenue) than the demand for justice. Yet, although the headlines both draw on Marcio’s words, the switch in headlines represents the first signs of the separation of different strands of the Grenfell story: with the raw emotion of unbearable loss becoming detached from the rage‐filled demand for justice.

That said, in this moment, anger and grief and hope and love and justice and truth are not yet cauterised from one another. Listen to Emanuela Disaro, mother of Gloria Trevisan, a young Italian architect who was trapped on the twenty‐third floor by flames coming up the single stairwell. In a phone call on the night of the fire, Gloria had told her mother, ‘I am so sorry I can never hug you again. I had my whole life ahead of me. It’s not fair’. Speaking through a translator, Emanuela told the inquiry on 29 May 2018 that she had taught her children not to hate, but that she felt a lot of anger: ‘I hope this anger is going to be a positive anger. I would like this anger to help to find out the truth of what happened’. A positive anger would, Emanuela hoped, lead to justice.

Anger, Truth, Justice. Intimately connected. Yet the Evening Standard’s West End Final edition headline suggested that this might not be enough: bound up in the demand for justice was the feeling that justice should also mean not having to fight for justice. Maria ‘Pily’ Burton, wife of Nicholas, was the seventy‐second victim of the fire: although rescued by firefighters from the nineteenth floor, she eventually died in January 2018 after months of medical care. Nicholas voiced the concerns of many of the bereaved. He told the Standard: ‘We should not have to fight so hard to be heard, but every step of the way so far has been a battle. You look at the Hillsborough families, still suffering after almost 30 years. We have to make sure we don’t have to wait 30 years for justice’ (Evening Standard, 21 May 2018 West End Final, p. 4; West End Final Extra, p. 5). The demand for justice and truth may be embedded in and motivated by anger, grief and suffering, but it also reaches out to feelings of sympathy, generosity and urgency. Or, their lack.

Nicholas Burton’s reference to the Hillsborough families is highly significant. Hillsborough refers to the deaths of 96 Liverpool fans, crushed to death on the Leppings Lane terraces of Sheffield Wednesday Football Club on 15 April 1989. In fact, if justice is the punishment of those held to be responsible, the Hillsborough families will never see it. Criminal trials associated with the disaster only began on 14 January 2019. Indeed, as a forewarning for those seeking justice for Grenfell Tower, the original intention to prosecute six people, including four senior police officers (including the chief constable), weakened. In the end, only two of the six faced trial: David Duckenfield, the police officer in command on the day, and Graham Mackrell, former Sheffield Wednesday club secretary and safety officer; charges including gross negligence manslaughter (Duckenfield) and breaches of safety regulations (Mackrell). The outcome of the trial, on 3 April 2019, was under a fortnight short of the thirtieth anniversary of the tragedy. While Graham Mackrell was found guilty of a single health and safety charge, and later fined £6,500 (with £5,000 costs), the jury could not agree a verdict for David Duckenfield. At his retrial in November 2019, after over 13 hours of discussion, the jury eventually found Duckenfield not guilty. Afterwards, the Hillsborough families asked a simple question: given that the 96 people killed at Hillsborough were found to have been unlawfully killed, who will be held to account? No one will ever be convicted of their deaths.

In the immediate aftermath of the Grenfell fire, the families and survivors were already acutely aware of the struggle for justice in the wake of the Hillsborough disaster. Indeed, groups from both tragedies would meet each other and share some of the same lawyers. In many ways, theirs is a shared struggle over truths: not just over what happened and whose testimony counts, but also over how these truths are to be interpreted and contextualised.