Читать книгу Bodies, Affects, Politics - Steve Pile - Страница 11

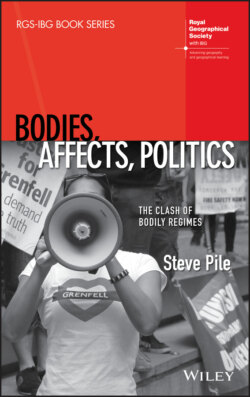

Justice for Grenfell

ОглавлениеAfter completing the commemorative hearings, on 4 June 2018, the Grenfell inquiry began to hear evidence about the events that led to the tragedy. The fire had begun when a Hotpoint fridge‐freezer had caught fire in Flat 16, Floor 4, where Behailu Kebede lived. It was Kebede who had first called the emergency services, asking them to come ‘quick, quick, quick’. Representing him was a lawyer who had also represented families at the Hillsborough inquiry, Rajiv Menon QC. Towards the end of a prepared statement, Rajiv Menon rounded upon the remit of the inquiry. He noted that the judge, Sir Martin Mason‐Brick, was unlikely to reverse his earlier decision and take the wider context into account. However, Menon was not to be deterred. It is worth hearing him at length (video is available at www.youtube.com/channel/UCMxYjfZsqLa8DanN0r2eNJw. Extract from minute 30:30 to 35:51):

There are certain stark irrefutable facts that one cannot simply ignore about the underlying social, economic and political reality and conditions that culminated in 71 people dying from smoke and fire in a high rise residential building, and a seventy‐second person dying a few months later, in one of the richest boroughs in one of the world’s great cities in one of the richest countries in the twenty‐first century. It is no coincidence that this fire occurred in a building consisting of social housing and former social housing purchased under the right to buy scheme and not in one of the posh swanky high‐rise residential buildings around London that cater to the extremely wealthy. It is no coincidence that this fire occurred in a building owned by a Tory flagship borough that has been at the forefront of promoting austerity cuts and deregulation and promoting business and profit over health and safety….

Off camera, someone in the audience shouts ‘Justice for Grenfell’; others clap in support. The presiding judge, Sir Martin Moore‐Brick, turns to the audience and solemnly insists that there will be no (further) interruptions of proceedings. Menon continues:

… It is no coincidence that the vast majority of the residents of Grenfell Tower were first or second‐generation migrants and refugees, the remaining residents being largely local people with long‐standing roots in the north Kensington area. Amongst the 72 that died, 23 countries and more were represented. So, race and class are at the heart of the Grenfell story whether we like it or not, whether the inquiry acknowledges it or not, whether the terms of reference are extended or not. Consequently, we say that what happened at the Grenfell Tower in the early hours of June last year was as political as it gets and symbolic of a deep inequality in our society.

The parallels between the Grenfell Tower and Hillsborough tragedies are not connected to the high number of victims, nor to the length of time that public inquiries take, nor to the uncertain possibility that anyone will ultimately face what Menon calls ‘real justice’ and ‘real accountability’. The parallels lie in deep and persistent inequalities in society, especially around class. Indeed, for writers such as Gordon Macleod (2018) and Stuart Hodkinson (2019), the core of this inequality is to be understood in the context of a systematic neoliberal assault on the welfare state, which has rendered public housing marginal, neglected, devalued and stigmatised. They point to the way that the local council, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, ignored regular complaints by the residents of Grenfell Tower about its safety, including the lack of a sprinkler system. To this is added the actions of an austerity‐driven ruling Conservative Party and unscrupulous private contractors. This view positions Grenfell in a long history of neoliberal assaults on the working class, especially on conditions of work and housing, since Thatcherism in the 1980s (see de Noronha 2019; and also Radical Housing Network, Hudson and Tucker 2019). Indeed, Hillsborough is easily seen as part of this assault.

As importantly, there is a shared struggle not only to voice the injustice, but to have their voices heard and recognised. Those voices are heard in moments. All too often, justice is undermined by a logic of blame: the claim for justice – formed around a much wider experience of inequality and injury – reduced to a demand for someone to be held responsible. Just as the police had sought to blame the victims, Liverpool fans, for their own deaths at Hillsborough, so the finger of blame has begun to be pointed at the firefighters for their supposed failure to evacuate people from the burning tower.

The parallels in the aftermath of the tragedies also lie in the difficulty of making anger, truth and justice stick together, especially over long periods of time. The parallel lies in the ease with which political institutions can detach heart‐break from anger, anger from the demand for justice, and justice from the political will to change public institutions, such as the police (Hillsborough) or the council (Grenfell): for example, by circumscribing the terms of reference of inquiries. Facts and affects are cauterised from one another: justice de‐politicised by its gradual assimilation into the legal process. Thus, broader questions about what justice looks like – which are as political as it gets – are transmuted into narrow socio‐technical questions, about cladding, about cost efficiency, about sprinkler systems. These are, of course, important issues, but this transmutation effectively converts the politics of social change into a politics of small changes.

What replaces justice is, as we have seen, heart‐breaking. Yet, the over‐riding heart‐break of the tragedy can itself shape how we understand what went before. It can be easy only to see the tragedies that led up to the tragedy, making the tragedy appear inevitable, the only possible outcome of all the injuries and inequities that went before. Yet, Grenfell Tower, as a microcosm of London life, has more than one story to tell.