Читать книгу Bodies, Affects, Politics - Steve Pile - Страница 16

Understanding Bodily Regimes: Between Rancière and Freud, between Overdetermination and Indeterminacy

ОглавлениеAs we have seen, the approach I take to thinking about the overdetermination and indeterminacy of bodies, affects and identities draws on Rancière. Rancière’s notion of the distribution of the sensible invites an analysis of bodies, affects and politics that focuses on the unconscious ways (which he calls an aesthetic regime) that the bodily senses are structured, such that only certain people are noticed, listened to and understood. I have previously suggested that aesthetic regimes (the unconscious structuring of the sensible) are multiple, inconsistent, mutable and (can) occupy the same space.

The idea that the processes of unconscious structuring are many has three implications that are significant for my approach. First, an account of the unconscious, and unconscious processes, cannot be restricted to singular functions and outcomes, such as repression and the Oedipus Complex (see Chapters 4 and 5). Second, unconscious structurings (plural) of the sensible might be in tension or conflict with one another (see Chapters 2 and 3), albeit in ways that are not easily perceived or that might be opaque or hidden or even repressed. Third, conflicts and tensions within and between unconscious structurings requires a dynamic understanding of unconscious processes, capable of illuminating and understanding the mutability of distributions of the sensible – and, for my purposes, of bodily regimes (as in Chapters 6 and 7). My approach builds on Freud’s account of the unconscious, yet this requires some recasting. Thus, Rancière’s discussion of Freud is instructive and illuminating – as it, helpfully for me, sets up the analytic architecture of this book.

Rancière’s intention, in writing The Aesthetic Unconscious (2001), is to understand Freud’s use of the Oedipus myth. This discussion does several interesting things for me: first, in answering the question of why Freud chooses the version of the myth that he does, Rancière provides both a demonstration of the effects, and affects, of specific aesthetic regimes and also (I argue) an example of the coexistence of aesthetic regimes; second, this then enables a re‐evaluation of the place of the myth in Freudian thought, which allows me to de‐privilege Oedipus in my version of Freud; and, thus, third, this opens up new avenues of thought for thinking with Freud about bodies, the unconscious and the distribution of the sensible.

In The Aesthetic Unconscious, Rancière boldly asserts that Freud’s understanding of the unconscious is predicated upon a particular aesthetic regime (p. 7). This aesthetic regime, for Rancière, creates a very particular set of dichotomies between thought and non‐thought, between knowing and not‐knowing, between seeing and blindness, between listening and hearing, between logic and sense. To substantiate his argument, Rancière turns to Freud’s discussion of the Oedipus myth, which provides Freud with a cornerstone for understanding the sexual anxieties of childhood, especially concerning castration (see Pile 1996, ch. 4). Rancière is especially interested in which version of the Oedipus myth Freud selects. I am persuaded by Rancière’s argument that this selection is significant and telling.

Freud’s account of the Oedipus myth is first spelt out in detail in the Interpretation of Dreams, under the section dealing with dreams about the death of loved ones (1900, pp. 275–278). He briefly outlines the myth, which involves both the unwitting fulfilment of a prophecy and also the vain efforts of people to avoid threatened disaster. Briefly, in Freud’s telling of the myth, King Laius of Thebes gives his infant child to a servant to get rid of because of a prophecy that Laius will be killed by his own son. Unable to kill the child, the servant gives the baby to a shepherd, Polybus. The child, Oedipus, grows up ignorant of his origins. Oedipus, later, kills Laius at a crossroad, not knowing that he has killed his father. Then, he marries Queen Jocasta, Laius’ widow and also his mother, and becomes king of Thebes. Oedipus’ life begins to unravel when a plague hits Thebes. Oedipus sends his brother‐in‐law, Creon, to the oracle at Delphi to discover the reason for the plague. Creon tells Oedipus that the problem is that the murderer of Laius has never been caught. Oedipus vows to find the murderer. He sends for the blind prophet, Tiresias. Tiresias is blunt: ‘You yourself are the criminal you seek’, he tells Oedipus. Oedipus simply cannot see how this can be true. In the ensuing argument, Oedipus mocks Tiresias’ blindness, and Tiresias retorts that it is Oedipus who is blind. As Tiresias leaves, he mutters that the murderer is son and husband to his own mother, brother and father to his own children, and a native of Thebes. Long story short, through a series of misdirections and revelations, eventually Oedipus comes to know that he is the murderer that he is seeking – and once he comes to a full realisation of his situation, he (famously) tears out his own eyes.

Why this version of the myth, Rancière asks? Other versions were available to Freud: for example, in 1659, Corneille wrote his own version; and, in 1717, Voltaire completed a version while in prison for 11 months (The Aesthetic Unconscious, ch. 2). For both Corneille and Voltaire, Rancière asserts, the original myth was not only too incredible, but also too gory for the sensibilities of their audiences. It was just implausible that Oedipus would not know that he was the murderer after being told so, bluntly and unambiguously, by Tiresias. More than this, the tearing out of his own eyes was plainly too literal and too explicit. Corneille and Voltaire sought to create more mystery around the identity of the murderer by introducing new, additional suspects. And they made sure that Oedipus’ denouement occurred off‐stage, unseen by the audience. Freud selected neither of these versions of the myth, nor indeed other versions; such as Dryden and Lee’s Oedipus: A Tragedy (1679), which centres on the love affair between Oedipus and Jocasta and portrays Oedipus as noble and heroic. Against expectation, Freud’s choice, Rancière argues, has nothing to do with incest (although Voltaire reduces the significance of incest in the story); it is instead about Freud selecting between aesthetic regimes.

In fact, Rancière argues, it would have been easier for Freud to have chosen either Corneille’s or Voltaire’s Oedipus, for these operate within the dominant representational regime of aesthetics, where characters and situations are taken literally. For both of them, it was simply impossible for audiences to suspend their disbelief when Oedipus cannot believe what Tiresias tells him. They believed their audiences simply would not understand that Oedipus was ‘in denial’ (as it is now popularly termed). Interestingly, this was apparently not the case for restoration period English audiences, as Dryden and Lee’s version followed Sophocles’ plot closely. Either way, for Rancière, neither incest nor Oedipus’ ability to hear or see the truth is at the heart of Freud’s choice. Rather, Freud chooses Sophocles’ Oedipus because the classical aesthetic regime (as Rancière calls it) places defects in the subject at the heart of tragedy. This sense of flaws in people’s characters provides Freud, in this view, with the ability to imagine unconscious processes, such as denial and castration anxiety.

Building on this observation, Rancière is now able to contrast the classical aesthetic regime with today’s dominant regime, the representational aesthetic regime. The pivotal difference between the representational and classical aesthetic regimes is the way they render the truth visible and invisible. Rancière argues that Freud selects the classical regime precisely because Oedipus cannot see his own truth, even when it is pointed out to him. This performs a particular cut through seeing and not seeing, the sayable and the unsayable, hearing and understanding, through knowing and not knowing. On one side, there is the knowing subject, Laius, who seems to be king of his own destiny; and, on the other side, there is a not‐knowing subject, Oedipus, who cannot even be king of who he is. It is the movement between these contradictory positions that animates the tragedy and what draws Freud to it. This is significant for Rancière.

And, for me, too. Rather than Oedipus being a lesson in what happens if you break the incest taboo (knowingly or not), this is about the relationship between knowing and not knowing, seeing and not seeing, hearing and not hearing (see Chapters 2 and 3): that is, the relationship between conscious and unconscious thought processes (see Chapters 3 and 4). And, as we see (in Chapters 5 and 6), between a repressive unconscious and a communicative unconscious. In particular, the (classical or representational) aesthetic regime is connected to the ideas of overdetermination and indeterminacy, where overdetermination is about how meaning is determined many times over through the distribution of the senses (that creates ways of knowing, seeing, hearing, feeling and so on) and where indeterminacy is a product of the epistemic cut between knowing and not knowing, seeing and not seeing, hearing and not hearing, feeling and not feeling and so on. My approach to these issues is empirical. The relationship between bodies, affects and politics is not to be decided in the abstract or in advance, but in context.

Rancière also asks why Freud draws upon Oedipus at all. That is, why does Freud draw upon a fictitious character from a stage play to model psychic structures? This question can be usefully extended: why does Freud draw on Shakespeare’s Hamlet (immediately following his discussion of Oedipus in The Interpretation of Dreams) or other artistic products, such as Michelangelo’s statue of Moses (Freud 1913), Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (Freud 1899), ‘The Sandman’ horror story by E.T.A. Hoffman (Freud 1919, which also establishes a connection between eyes and the fear of castration), and the like? For me, these examples perform two significant functions. First, these examples, for Freud, bear witness to unconscious processes through the aesthetic forms they take. Second, they reveal that unconscious processes bleed through life, in all its forms: that is, given the focus of this book, through bodies, through affects and through politics. Thus, as this book is to bear witness to the ‘aesthetic unconscious’ of bodies, affects and politics, I draw on a range of examples: I have selected Freud’s case studies (Chapters 4, 5 and 6), autobiography (Chapters 2 and 3), novels (Chapter 2), Hollywood movies (Chapter 5) and art (Chapter 7). Importantly, for my argument, the unconscious is not confined to a particular space, such as the consulting room, and especially not to the brain or the mind of the individual.

The Oedipus myth is normally taken as significant because it places repression, sexual anxieties associated with parents and the body, at the heart of the analysis of the symptom. However, what Rancière highlights is the way Freud traces the slippages between knowing and not knowing, between hearing and not hearing, between seeing and not seeing. So, the imperative that this book follows, drawing on both Rancière and Freud, is two‐fold. First, to map out the coexistence of different distributions of the sensible and their policing – which I will call bodily regimes (following Frantz Fanon, see Chapter 2). Second, to chart the ways that these coexistent bodily regimes are imbricated and experienced, especially including the ways that these create tensions and antagonisms for the subject (building from Chapter 2 to Chapter 3). In Chapters 2 and 3, I lay particular emphasis on the role of skin as a target for, and a manifestation of, coexisting bodily regimes. These two chapters are an asymmetrical pairing, showing how people can, and cannot, inhabit the uncomfortable imposition of bodily regimes differently.

The coexistence of bodily regimes can imply that they are somehow discrete, such that there cannot be movement through or across bodily regimes; more than this, that bodily regimes are somehow confined to bodies themselves – and not ‘of the world’. Chapters, 4 and 5 explore the topologies and topographies of psychic space. In these chapters, we learn about the slippages between bodily regimes, as the world touches upon the psyche and as the psyche touches upon the world. Significantly, this involves the shifts and whorls of affects through the body and the social. To understand this, these chapters draw heavily on the idea of the Möbius strip. The strip is mostly understood as a way to describe the inversion of inside and outside (and is aligned therefore with the torus and the Klein bottle). However, key to these chapters is the movement along the strip that creates the inversion. It is movement that creates the tension between overdetermination and indeterminacy (at each point). Significantly, the strip also necessarily has width, which requires factoring in lateral movement – as an additional dimension of indeterminacy.

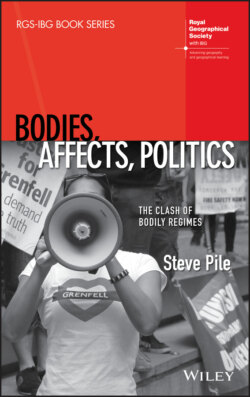

To understand the indeterminacy of bodies and affects, I focus on unconscious communication in Chapters 5 and 6 – following Paul Kingsbury and my identification of the unconscious and transference as two of the four fundamentals of psychoanalytic geography (2014, Ch. 1). These chapters take us far from an Oedipally‐centred version of Freud. Instead, these chapters develop a model of Freudian thought that is focused on the ways that thought and non‐thought (as in thoughts in the unconscious) are produced and repressed, but also represented, circulated and communicated. This brings us fully into a model of the subject that is radically open to the other, which necessarily begs fundamentally questions about the nature of the distribution of the senses, where no distribution – or bodily regime – can be taken as read. This then takes us (in Chapter 7) to the art of Sharon Kivland. Here, we are back on Rancière’s terrain, the aesthetic. However, we are now attending to the indeterminacy of bodies, affects and politics that arises from the dynamics and disruptions of the aesthetic unconscious. This brings us full circle, back to the politics of bodies and affects that emerge from the clash between bodily regimes. However, what we now know (from the chapters within the book) is that these clashes emerge not just from the split between thought and non‐thought (etc.), not solely from the coexistence of different forms of splitting (i.e. the coexistence of distributions of the sensible, of bodily regimes), but from the movement along, across and between them. With this idea, it will be possible to return to Grenfell (in the Conclusion in Chapter 8) to think once more about the interweaving of bodies, affects and politics.

The next two chapters focus on skin, both as an overdetermined location where identity, difference and experience are seemingly settled and known, but also where class, race, gender, sexuality and the relationships between them are revealed to be mutable and indeterminate.