Читать книгу Ishiro Honda - Steve Ryfle - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

FORGING BONDS

With its progressive acumen, PCL attracted filmmakers more concerned with their craft than with becoming studio power brokers. From 1934 to 1935, several big-name directors left larger, established studios for the young company. Two of these men became dominant figures on the PCL lot: Mikio Naruse, who defected from Shochiku, would develop into one of Japan’s most celebrated directors, a master of sophisticated shomin-geki (working-class drama) films focusing on the plight of women; and Kajiro Yamamoto, from Nikkatsu, was a skilled technician, whose work would achieve tremendous commercial success. Naruse and his staff were considered the artistic group, while Yamamoto’s team was a versatile bunch who developed the type of program pictures that would come to define the studio’s brand. Yamamoto had a paternal attitude toward his devoted corps of assistants, a commitment to pass on the craft to the next generation. Bespectacled, handsome, and perpetually well dressed, Yama-san, as he was fondly called, became Honda’s greatest teacher.

Born in Tokyo in 1902, Yamamoto was unimpressed with early, theater-influenced Japanese cinema, but he was inspired by pioneering director Norimasa Kaeriyama’s work, including The Glow of Life (Sei no kagayaki, 1919), considered revolutionary for its lack of stage conventions and its use of actresses over female impersonators. In 1920 Yamamoto dropped his economics studies at Keio University and joined Nikkatsu’s Kyoto studios. For the next few years he wrote screenplays, worked as an assistant director, and acted under the pseudonym Ensuke Hirato. He began directing films in 1924.

Yamamoto had caught Iwao Mori’s attention as a member of the old Nikkatsu Friday Party, and Mori lured him over to PCL in 1934 to direct the first of many films starring Kenichi “Enoken” Enomoto, known as Japan’s “king of comedy.” Yamamoto was naturally curious and enjoyed genre hopping; he made musicals, melodramas, and later crime thrillers and salaryman comedies. At the height of World War II he would direct several big-budget, nationalist war propaganda films that were highly successful at the box office. His career would last well into the 1960s.

Honda became one of Yama-san’s most trusted disciples. From Yama-san, Honda learned all aspects of the craft with an emphasis on writing, as Yamamoto stressed that directors must write screenplays. While shooting, Yamamoto often scribbled in a journal, a practice that Honda adopted.

Honda also learned from Yamamoto how to treat his staff. Yama-san would throw parties at his home for cast and crew as a way of creating a family atmosphere; when Honda became a director, he would do the same for his charges. Yamamoto had a soft, quiet demeanor and always treated his protégés in equal terms. He called them by name: It was always Honda-san or the more familiar Honda-kun, never “hey you” or the condescending language other directors often used. He never sent them to buy cigarettes or do menial errands. Years later, Honda would show the same respect to his own crew members.

“He didn’t want yes-men around him,” Honda recalled. “We always went drinking with him, though. But he was never an autocrat … Since [Yamamoto] was so knowledgeable, his stories were always interesting. He was also frank on the set and would ask me to write parts of the script. And then he would use it.”1

Honda described Yamamoto as a connoisseur. “He was more like a free spirit. He was not like us, he was not all about movies. Movies were only a part of his life. He liked other things too, such as music. So I learned a lot of things from him.”2

———

Honda’s two-year absence had stalled his career, while his peers advanced. His first job upon returning to work was on Yamamoto’s two-part drama A Husband’s Chastity (Otto no teiso, 1937). Senkichi Taniguchi, Honda’s friend since the Friday Party days, was now Yamamoto’s chief assistant director (or first assistant director), while Honda remained a second assistant director. Still, Honda accepted his situation and held no resentment toward the studio or his rank-and-file cohorts.

Released in April 1937, A Husband’s Chastity marked several milestones. It was a big hit, the first PCL film to turn a profit. It did so despite the refusal of Shochiku, Nikkatsu, and other studios to exhibit PCL movies in their theaters, a retaliation against PCL’s practice of hiring away its competitors’ actors and directors. For Honda, the film had another significance: it marked his meeting with an intensely ambitious new recruit, a man who would become his lifelong best friend.

The job of assistant director in the Japanese studios was not unlike that in Hollywood: keeping the production schedule, preparing call sheets, maintaining order on the set, and so on. Unlike their American counterparts, however, the Japanese were viewed as directors-in-training. At the time Honda joined PCL, trainees were hired strictly through personal connections, and so there were always too few assistant directors on the lot. In 1936, PCL chose ten prospective assistant directors from the general public for the first time to help bolster the ranks. All the new recruits had degrees from top universities except for one. Akira Kurosawa, at twenty-five, had just a junior-high-school education, but his enthusiasm and knowledge of the visual arts impressed the examiners.3

“[We] were placed in a sort of cadet system, like at military schools,” remembered Kurosawa. “We had to train in every area, even film printing. We rotated through a series of departments.”4 Only after thorough schooling in camera operation, editing, writing, costumes, props, scheduling, budgeting, and other areas could a trainee ascend from the ranks of third and second assistant to earn the coveted title of first assistant director.

PCL’s assistant directors put in long, hard days, worked well into the night, longed for sleep, and put saliva into their weary eyes to help them see clearly. Kurosawa quickly noticed Honda’s energy and diligence; he nicknamed his new friend “Honda mokume no kami”—Honda, keeper of the grain.

“[Honda] was then second assistant director, but when the set designers were overwhelmed with work, he lent a hand. He would always take care to paint following the grain of the wood on the false pillars and wainscoting, and to put in a grain texture where it was lacking … His motive in drawing in the grain was to make Yama-san’s work look just that much better. Probably he felt that in order to continue to merit Yama-san’s confidence, he had to make this extra effort. The confidence Yama-san had in us created this attitude. And of course this attitude carried over into our work.”5

Born on March 23, 1910, in Tokyo and standing five foot eleven and a half, Kurosawa was a year older and several inches taller than Honda and seemed worldly and larger than life. He was introduced to the cinema by his father, “a strict man of military background” who nevertheless loved movies and believed they had educational value.6 Growing up, Kurosawa was exposed to many different types of films, from Japanese silents to the Zigomar crime serials to Abel Gance’s The Wheel (La Roue, 1923). While Honda’s career was interrupted repeatedly by the war, Kurosawa apprenticed under Yamamoto for five straight years, becoming Yama-san’s “other self.”

Having just returned from China, Honda had no place of his own. He moved in with Kurosawa, who had a one-room apartment on the second floor of PCL’s employee dorm, Musashi-so, located near the studio in the Seijo neighborhood of Tokyo’s Setagaya Ward. They were opposites: Kurosawa opinionated and driven, Honda quiet and unassuming.

“Kuro-san was like a mentor-friend to me,” said Honda. “Even though he was the same age, I felt that way towards him because of his great talent.” Kurosawa, a gifted painter from a young age, introduced Honda to the work of calligrapher and artist Tessai Tomioka, an originator of the neotraditional Nihonga style, and other painters he was passionate about. The two friends discussed art and film at great length. And as years passed and Honda would go to and from the battlefront, they discussed the war and Japan’s escalating militarism.

“Honda and I agreed that it would be a disaster if Japan won, if the incompetents in the military stayed in power,” Kurosawa recalled. “Honda said this too. What we’d most hate was to see those military guys have their own way if we won the war, and drive the country into a deeper mess.”7 Thanks to his father’s respected name in the military, Kurosawa was exempted from duty. A draft official generously classified him as physically unfit to serve.

———

On the PCL back lot they were known as the Three Crows: Akira Kurosawa, Senkichi Taniguchi, and Ishiro Honda, three up-and-coming assistant directors who, as Kajiro Yamamoto’s top protégés, commanded a bit of respect. No one remembers how the nickname came about, but they seemed significantly taller than everyone else, a trio of “very handsome fellows” who had “a little different vibe,” as a friend remembered. They seemed to be together constantly, during the workday and after hours. Theirs was a close-knit and sometimes tumultuous camaraderie based on shared interests and ambitions.

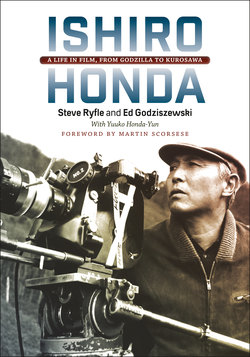

The three crows—Kurosawa, Honda, and Taniguchi—with mentor Kajiro Yamamoto, late 1930s.Courtesy of Kurosawa Productions

Each crow was a bird of a different feather. Taniguchi was the youngest, born February 12, 1912, in Tokyo. He wore eyeglasses, was perpetually tan, and was known for his ever-running mouth, sense of humor, and sharp tongue. Yamamoto encouraged his assistants to speak freely, and Taniguchi didn’t hesitate. “Taniguchi was merciless,” said Kurosawa. “One day he said, ‘Yama-san, you’re a first-rate screenwriter but a second-rate director.’ Yama-san just laughed.”

Taniguchi served in the war, but his stint was shorter than Honda’s and didn’t stall his career. “[Honda] had really bad luck,” Taniguchi said in 1999. “He was drafted when he was young, and just at a time when he could have learned so much about making movies.”8

Kurosawa was the most volatile among them, complex and opinionated and uncompromising. When he first arrived at PCL, Kurosawa had no place of his own so he’d crashed on Taniguchi’s futon, but Taniguchi grew annoyed and kicked him out. Honda was the quiet and contemplative one, not nearly as aggressive. As Kurosawa biographer Stuart Galbraith IV writes: “They called one another by nicknames after the Kanji characters in their family names: ‘Kuro-chan’ (‘Blackie’), ‘Sen-chan’ (‘Dear Sen,’ ironic, given his temperament), and ‘Ino-chan’ (‘Piggy’).”9

They drank, talked, and argued, and in between films they would camp in the mountains for several days. Honda, the Yamagata boy and soldier, was an able hiker, as was Taniguchi. Their trips invariably began peacefully but ended with Kurosawa and Taniguchi arguing incessantly, with Honda playing peacemaker.

Each man took what he learned from Yama-san and forged his own path. Kurosawa became a relentless pursuer of perfection. Taniguchi would make a number of notably ambitious early films, including the first adaptation of Yukio Mishima’s The Sound of the Waves (Shiosai, 1954)—a film that created a sensation for hints of erotic nudity10—then finished his career with a series of mainstream programmers. Honda most closely emulated his mentor’s example by becoming a versatile maker of successful program pictures and putting his heart and soul into those that mattered most to him. The friendships endured long after their early struggles. While Honda went to war, Kurosawa would help his wife care for their children, and much later Kurosawa would make Honda his most trusted adviser. Taniguchi would be like an uncle to Honda’s kids; and years later, when Honda later bought a bigger house in Okamoto, a neighborhood in the western part of Tokyo’s Setagaya Ward, Taniguchi and his third wife, actress Kaoru Yachigusa, star of Honda’s The Human Vapor, liked it so much they built a home nearby.

———

In the mid-1930s, with PCL struggling financially, founder Yasuji Uemura had sold a controlling interest in the studio to Ichizo Kobayashi, a railroad executive, real estate tycoon, and the entertainment mogul behind the legendary Takarazuka Grand Theater and its famous all-girl music and dance revue. Kobayashi also owned a chain of cinemas, and acquiring PCL was part of his strategy to supply his movie houses with product. Together with studio chief Iwao Mori, Kobayashi also aimed to shake up the business, building on PCL’s innovative model to create Japan’s most modern film company.

On August 27, 1937, Kobayashi merged PCL with another small production outfit to form Toho Motion Picture Distribution Company, later the Toho Motion Picture Company.11 According to film critic Jinshi Fujii, “Toho’s entrance into the film business caused the structural reorganization of the Japanese film industry … [S]trict budgetary control was put into practice, the producer system was set up, and vertical integration of production, distribution, and exhibition was achieved … [T]he Hollywood-style system was transplanted to Japan almost completely.” Before long, observers would note that Toho had also “[overwhelmed] other companies in terms of film technology … [it] imported new filmmaking equipment from America four or five years [earlier].”12

For Honda and Kurosawa, the excitement of working at the upstart new studio was tempered by long hours and a meager salary of ¥28 per month.13 Assistant directors were paid less than office workers because, with location pay and other incentives, it was possible to earn much more, though it rarely worked out that way. Their social life revolved around drinking, and if Yama-san wasn’t buying, they drank on credit. Often there was no cash in their pay envelopes, only receipts for vouchers redeemed at the studio commissary and IOUs collected by local bars and clothing stores. On payday, they were already broke.

The dormitory where Honda roomed with Kurosawa had a pool table, an organ, and other diversions. When Honda, Kurosawa, and their friends weren’t hitting the bars, they would congregate there, often in Kurosawa’s little room, drinking and discussing art and cinema. This group included Sojiro Motoki, a future producer who would play an important part in the careers of both Honda and Kurosawa, and a pretty editor’s assistant named Kimi Yamazaki.

Kimi was six years younger than Honda, born January 6, 1917, in Mizukaido, Ibaraki Prefecture, the youngest of eight children. She was different from other women her age; she could hold her own in serious film discussions with the boys and hold her liquor when the beer and sake were poured. Kimi was self-confident and assertive, a modern Japanese woman intent on being more than an office lady or salesclerk, the typical woman’s jobs then.

It was Morocco, the film that Honda had spent so much time studying, that compelled Kimi to join the industry. She worked briefly for a small newsreel outfit, then passed Toho’s entrance exam and became assistant to Koichi Iwashita, one of Japanese cinema’s most respected editors. One day, Honda stopped by the editing room to say hello, and Iwashita introduced the young assistant director to his new employee. Sparks didn’t fly right away, though. “I still remember how he was wearing this weird looking suit,” Kimi recalled. “He was unfashionable, so unpolished, just back from the war. Compared to guys like Kuro-san then, he was hardly dashing.”

After she was promoted to the position of “script girl,” Kimi worked late hours on movie sets. Commuting from her parents’ home was impractical, so she moved into the dorm and became Kurosawa and Honda’s neighbor. The boys grew so accustomed to her presence that if she didn’t show up for their nightly klatch, one of them would rap on her door. One night, Kimi begged off with a severe headache, and Honda went to fetch some medicine. “This was the first time I thought, ‘Wow, he is such a nice guy.’ But it wasn’t like I was head over heels … As time passed, I got to know everyone [in the dormitory]…. But I think I was most attracted to his warmth, his heart.”

Honda immersed himself in his job, working on more than a dozen films between 1937 and 1939 and slowly ascending the ladder. Though Yamamoto was his primary teacher, he also apprenticed under other prominent studio directors, studying their work styles and habits. Honda was an assistant director on Humanity and Paper Balloons (Ninjo kami fusen, 1937), an acclaimed early jidai-geki and the last film by director Sadao Yamanaka, a fellow army recruit who would die as a soldier in China the following year. Honda also worked for the jidai-geki specialist Eisuke Takizawa. Sometimes, Honda would visit the set of a Mikio Naruse production to observe the celebrated director at work, which led Naruse to tap Honda as third assistant on two acclaimed early pictures, Avalanche (Nadare, 1937) and Tsuruhachi and Tsurujiro (Tsuruhachi Tsurujiro, 1938).

———

Summer 1937: Honda and Senkichi Taniguchi, having been there from the founding days of PCL, were now the two longest tenured assistant directors on the lot. Taniguchi had been Yamamoto’s chief assistant for about a year, but he now was transferred to a front office job, using his knowledge of production to help curb expenditures. Needing a new chief assistant, Yamamoto boldly promoted Kurosawa, a third assistant director with only about a year on the job, catapulting him over Honda and others with more experience. Beginning with the drama The Beautiful Hawk (Utsukushiki taka, 1937), Kurosawa was Yamamoto’s right-hand man, a role he would thrive in.14

Honda, meanwhile, continued his Sisyphean progress and was finally promoted to first assistant director, a bit ironically, on Takeshi Sato’s Chocolate and Soldiers (Chocolate to heitai, 1938). An early example of the war propaganda films supported by the government, it told the story of a small-town man drafted and sent to China, leaving behind his wife and child.15

“[When] I came back from the front, everyone’s position had changed,” Honda said. “I was the second or third assistant director for the longest time. But after all, I think it worked out better for me.” He was now among the most experienced first assistants on the lot. “I just wanted to be by the camera. That is what I liked.”16

———

As illustrated by his friendships, Honda gravitated toward people much different from himself, and this seems to explain his unusual bond with Kimi. “She was very energetic, and her personality could be completely different from me,” he once remarked. “Maybe that is why we got along so well.”17 Friends thought they were mismatched; Kurosawa called them “total opposites.”

The two were spending more and more time together. Kimi earned more than Honda did, so when they went out, she would often buy the drinks. Though they didn’t work on the same film often and seldom saw one another during the day, they walked to the studio together each morning and joined their regular crowd in the evening. This routine had continued for more than a year when, one morning, Honda and Kimi were standing on the Fujimi Bridge, a small pedestrian overpass in Seijo that, on cloudless days, offered breathtaking views of Mount Fuji and the Tanzawa Mountains to the west. Honda asked, matter-of-factly, “Want to get married with me?”

“Everybody was just friends back then,” Kimi said. “I had no idea he viewed me as more than just that. I was so surprised when he asked me. But I recall feeling really warm when I was with him, and I never got sick of being around him. I wondered what he saw in me. I was pretty naïve, simple, and innocent. So I said, ‘Sure, OK.’ Just like that.”

In proposing, Honda was breaking with tradition once again. The great majority of marriages were customarily arranged by a go-between, acting on the parents’ behalf, who screened prospective partners for compatibility based on family reputation, income, profession, education, and other factors.18 Those who deigned to choose a spouse against their parents’ wishes might be shunned. Kimi’s mother, Kin Yamazaki, supported the couple’s engagement but, perhaps unsurprisingly, her father was strongly opposed. Heishichi Yamazaki was a wealthy and conservative landowner in Ibaraki, north of Tokyo; it would be unacceptable for his daughter to marry a country boy with unclear prospects for gainful employment in a new, unproven industry. Kimi stood firm on her wishes, and her father stood equally firm, responding simply, “Suit yourself.” With those words, Heishichi denied the couple the financial support they so desperately needed. Once Kimi quit her job, as was customary for new wives, the pair would have to survive on Honda’s meager salary. Honda’s more unconventional family, by contrast, congratulated the couple. Takamoto wrote to Kimi, “No matter what others say, believe in each other and live with confidence.”

Honda was twenty-seven years old, Kimi twenty-two. On their wedding day in March 1939, they filed papers at city hall, paid their respects at Meiji Shrine, and went home. It was so uneventful that, years later, neither one could recall the precise date. There was no ceremony, celebration, or honeymoon. With little money, the pair moved into a tiny, one-room apartment with a shared bathroom.

Before long Kimi was pregnant, complicating the newlyweds’ financial struggles. Although Kimi’s father would never openly approve of the marriage, the news of a grandchild on the way caused Heishichi to quietly relent; and he sent her a bank book with a ¥1,000 balance, a then sizeable gift. “His head clerk came to give it to me, saying, ‘This is from the master,’” Kimi remembered. “My mother expressed her love in a very kind manner, but [my father’s] love was more from afar.” Each month Heishichi would send money to Kimi, enabling the couple to move into a small rented house on the south side of Seijo, about five minutes from the studio, where they would start their family.

It was a happy time, but short-lived.