Читать книгу Ishiro Honda - Steve Ryfle - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

[Japanese] critics have frequently dismissed Honda as unworthy of serious consideration, regarding him merely as the director of entertainment films aimed at children. By contrast, they have elevated Kurosawa to the status of national treasure. As for the men themselves, by all accounts Honda and Kurosawa had nothing but respect for one another’s work. Prospective studies of the history of Japanese cinema should therefore treat Honda’s direction of monster movies and Kurosawa’s interpretation of prestigious sources such as Shakespeare as equally deserving of serious discussion.

— Inuhiko Yomota, film historian

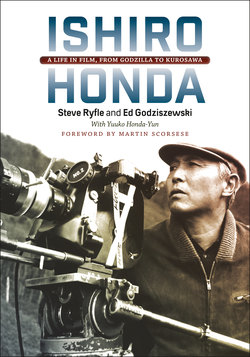

In August 1951, as Japan’s film industry was emerging from a crippling period of war, labor unrest, and censorship by an occupying foreign power, the press welcomed the arrival of a promising new filmmaker named Ishiro Honda. He was of average height at about five-foot-six but appeared taller to others, with an upright posture and a serious, disciplined demeanor acquired during nearly a decade of soldiering in the second Sino-Japanese War. There was something a bit formal about the way he spoke, never using slang or the Japanese equivalent of contractions—he wasn’t a big talker for that matter, and was usually immersed quietly in thought—yet he was gentle and soft-spoken, warm and likeable. A late bloomer, Honda was already age forty; and if not for his long military service, he likely would have become a director much earlier. He had apprenticed at Toho Studios under Kajiro Yamamoto, one of Japan’s most commercially successful and respected directors; and he hinted at, as an uncredited Nagoya Times reporter put it, the “passionate literary style” and “intense perseverance” that characterized Yamamoto’s two most famous protégés, Akira Kurosawa and Senkichi Taniguchi, who were also Honda’s closest friends.

“Although their personalities may be similar, their work is fundamentally different,” the reporter wrote. “Ishiro Honda [is] a man who possesses something very soft and sweet, yet … his voice is heavy and serene, giving off a feeling of melancholy that … does not necessarily suit his face. The many years he lost out at war were surely a factor…. The deep emotions must be unshakeable.”

Honda’s inclinations, it was noted, were more realistic than artistic. He didn’t share the “Fauvism” of Kurosawa’s painterly compositions.1 He took a dim view of the flashy, stylistic film technique that some of his contemporaries, including Kurosawa and famed director Sadao Yamanaka, with whom Honda had also apprenticed, borrowed from American and European cinema of the 1920s and 1930s.

“I do not want to deceive by using superficial flair,” Honda said. “Technique is an oblique problem. The most important thing is to [honestly] depict people.” A beat later, he was more introspective: “This may not really be about technique. Maybe it is just my personality. Even if I try to depict something real, will I succeed?”

The newspaper gave Honda’s debut film, The Blue Pearl, an A rating, declaring it “acutely magnificent.” And with a bit of journalistic flourish, the paper contemplated the future of the fledgling director, admiring his desire to “practice rather than preach, [to] cultivate the fundamentals of a writer’s spirit rather than being preoccupied with technique, a fascination with the straight line without any curves or bends…. How will this shining beauty, like a young bamboo, plant his roots and survive in the film industry?”2

———

A tormented scientist chooses to die alongside Godzilla at the bottom of Tokyo Bay, thus ensuring a doomsday device is never used for war. An astronaut and his crew bravely sacrifice themselves in the hope of saving Earth from a wayward star hurtling toward it. Castaways on a mysterious, fogged-in island are driven mad by greed, jealousy, and hunger for a fungus that turns them into grotesque, walking mushrooms. A pair of tiny twin fairies, their island despoiled by nuclear testing, sing a beautiful requiem beckoning the god-monster Mothra to save mankind. Invaders from drought-ridden Planet X dispatch Godzilla, Rodan, and three-headed King Ghidorah to conquer Earth, but an alien woman follows her heart and foils their plan. A lonely, bullied schoolboy dreams of a friendship with Godzilla’s son, who helps the child conquer his fears.

The cinema of Ishiro Honda brings to life a world of tragedy and fantasy. It is a world besieged by giant monsters, yet one in which those same monsters ultimately become Earth’s guardians. A world in which scientific advancement and space exploration reveal infinite possibilities, even while unleashing forces that threaten mankind’s very survival. A world defined by the horrific reality of mass destruction visited upon Japan in World War II, yet stirring the imaginations of adults and children around the world for generations.

Honda’s Godzilla first appeared more than sixty years ago, setting Tokyo afire in what is now well understood to be a symbolic reenactment of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was a major hit, ranking eighth at the Japanese box office in a year that also produced such masterpieces as Seven Samurai, Musashi Miyamoto, Sansho the Bailiff, and Twenty-Four Eyes. It was subsequently sold for distribution in the United States, netting sizeable returns for Toho Studios and especially for the American profiteers who gave it the exploitable new title, Godzilla, King of the Monsters! If the triumph of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon—which took the grand prize at the 1951 Venice International Film Festival, and subsequently received an honorary Academy Award—had brought postwar Japanese cinema to the West, then it was Honda’s monster movie that introduced Japanese popular culture worldwide.

Only fifteen years after Pearl Harbor, Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (famously reedited with new footage starring Raymond Burr, yet featuring a predominantly Japanese cast) surmounted cultural barriers and planted the seed of a global franchise. It was the forerunner of a westward Japanese migration that would eventually include everything from anime and manga to Transformers, Power Rangers, Tamagotchi, and Pokémon. Godzilla became the first postwar foreign film, albeit in an altered form, to be widely released to mainstream commercial cinemas across the United States. In 2009 Huffington Post’s Jason Notte declared it “the most important foreign film in American history,” noting that it had “offered many Americans their first look at a culture other than their own.”3

An invasion of Japanese monsters and aliens followed in Godzilla’s footsteps. With Rodan, The Mysterians, Mothra, Ghidorah the Three-Headed Monster, and many others, Honda and special-effects artist Eiji Tsuburaya created the kaiju eiga (literally, “monster movie”), a science fiction subgenre that was uniquely Japanese yet universally appealing.

Honda’s movies were more widely distributed internationally than those of any other Japanese director prior to the animator Hayao Miyazaki. During the 1950s and 1960s, the golden age of foreign cinema, films by Kurosawa, Mizoguchi, and other acclaimed masters were limited to American art house cinemas and college campuses, while Honda’s were emblazoned across marquees in big cities and small towns—from Texas drive-ins to California movie palaces to suburban Boston neighborhood theaters—and were also released widely in Europe, Latin America, Asia, and other territories. Eventually these films reached their largest overseas audience through a medium they weren’t intended for: the small screen. Roughly from the 1960s through the 1980s, Godzilla and company were mainstays in television syndication, appearing regularly on stations across North America. Since then, they have found new generations of viewers via home video, streaming media, and revival screenings. Today, the kaiju eiga has gone global. It continues to be revived periodically in Japan, while Hollywood, via Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim (2013) and two big-budget Godzilla remakes (1998 and 2014), has fully co-opted it.

Honda’s remarkable achievement went entirely unnoticed in the early years, because of several factors. First, there was a critical bias against science fiction films; in the 1950s, even exemplary genre pictures such as Howard Hawks’s The Thing (1951), Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), and Fred M. Wilcox’s Forbidden Planet (1956) “were taken to be lightweight mass entertainment, and even in retrospect they have rarely been credited with any substantial degree of aesthetic or intellectual achievement,” observes film historian Carl Freedman.4 Critics tended to focus on technical merits, or lack thereof, rather than artistic value or content.

Stereotypes about Japan and its then-prevalent reputation for exporting cheap products were another obstacle, compounded by US distributors’ tendency to radically alter Honda’s films by dubbing them into English (often laughably), reediting them (sometimes very poorly), or giving them ridiculous new titles such as Attack of the Mushroom People. This process could marginalize Honda’s authorship, or render it invisible: he sometimes shared a director’s credit with the Americans who had chopped up his movies, and overseas theatrical posters often excluded his name entirely.

As Christopher Bolton, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay Jr., and Takayuki Tatsumi note in their survey of Japanese science fiction, Robot Ghosts and Wired Dreams:

In the U.S., the Japanese monster film became the archetype for cheap, cheesy disaster movies because of … cultural and technological interference patterns … In many cases, the original films’ anamorphic widescreen photography, which lent images greater scale and depth when properly projected, was reduced for American showings to a smaller format; the original stereophonic soundtracks (among the most technically innovative and musically interesting in the medium at the time) were [replaced] and rearranged; and additional scenes with American actors, shot on different screen ratios, were added … The American versions inevitably stripped out the stories’ popular mythological resonances, their evocation of Japanese theater, and the imaginary management of postwar collective emotions.5

Such distractions and biases were evident in the writings of American reviewers. Variety called Mothra, one of Honda’s most entertaining genre films, “ludicrously written, haphazardly executed”; of The Mysterians, it wondered if “something was lost in translation.” Japanese film critics, meanwhile, tended to dismiss kaiju eiga as juvenile gimmick films. The genre’s domestic marginalization as an otaku (fan) phenomenon was cemented in 1969 with the World of SF Film Encyclopedia (Sekai SF eiga taikan), a landmark volume covering sci-fi films by Honda and his contemporaries. Though published by the respected Kinema Junpo film journal, its author was not a mainstream critic but “monster professor” Shoji Otomo, editor of Shonen Magazine, a weekly children’s publication.

Thus, Honda’s career is one of contradictions. In Japan he was an A-level director, but abroad he was known only as a maker of B movies. Despite his large output and the popularity, longevity, and influence of his work (director Tim Burton once called Honda’s genre pictures “the most beautiful movies in the whole world”), there has been relatively little study of it beyond Godzilla. Honda never had a number-one hit, but his films consistently performed well at the Japanese box office and netted substantial foreign revenue; yet even commercial success did not lead him to make the projects he was most passionate about.

Not unlike the English director James Whale—who, despite making war dramas, light comedies, adventures, mysteries, and the musical Show Boat (1936), is most widely remembered for directing Universal’s Frankenstein (1931), The Invisible Man (1933), and Bride of Frankenstein (1935)—Honda became known for one genre even though his output included documentaries, dramas, war films, comedies, melodramas, and even a yakuza (gangster) actioner and a sports biopic. Of Honda’s forty-six features, nearly half had nothing to do with sci-fi, and more than a few of these films are excellent, though underappreciated. The “shining beauty” who planted his roots in the business in 1951 would prove a versatile craftsman driven to, as he said, “depict something real.”

Honda’s career began with four subdued dramas about young people navigating the changing postwar landscape, with themes common to gendai-geki (modern drama) films reflecting social friction in contemporary Japan. After The Blue Pearl came The Skin of the South (1952), The Man Who Came to Port (1952), and the teen melodrama Adolescence Part 2 (1953). Then a pair of dramas about the human cost of Japan’s wartime hubris, Eagle of the Pacific (1953) and Farewell Rabaul (1954), presaged the cautionary tale Honda would tell next in Godzilla (1954).

As Japan’s harsh economic conditions slowly improved, Honda entered a second, more optimistic period, and through the early 1960s he would frequently incorporate music and humor in both his monster and mainstream films. Although the press had initially raised lofty expectations, Honda now became a member of Toho Studios’ stable of contracted program-picture directors, craftsmen respected for their commercial durability and their ability to deliver films on time and on budget, while largely toiling in the critical shadows of the resurgent early masters (Yasujiro Ozu, Mikio Naruse) and rising auteurs (Kurosawa, Kon Ichikawa, Masaki Kobayashi, among others). As such, Japan’s critics essentially dismissed him; of his films, only The Blue Pearl made Kinema Junpo’s annual best-of list. It would be decades before Godzilla would earn worldwide critical acceptance as a significant entry in Japan’s postwar cinema, and even longer before several of Honda’s nongenre films would begin to be reappraised.

Though he was instrumental in creating iconic films known around the globe for more than sixty years, Honda has been overlooked as a director deserving scholarly attention. That his talents and interests went far beyond the narrow limits of the monster-movie genre, and that he effectively had two overlapping but very different careers, one invisible outside Japan, remains little known. And so his story has not really been told, and his body of work not fully considered. This book looks at Honda’s life, reexamines his films, recognizes his substantial achievements, and casts light on his contributions to Japanese and world cinema. Through a combination of biography, analysis—including the first study, in any language, of his entire filmography—and industrial history, it not only tells how Honda created a world of fearful yet familiar monsters, but also recalls the experiences and relationships that informed his movies, including his long years at war and the endless nightmares that followed. And it explores a lasting mystery of Honda’s legacy: why, for reasons difficult to understand, he did not parlay the broad popularity of his genre pictures into the freedom to make the films he most wanted to; and why, while close friends and colleagues Akira Kurosawa and Eiji Tsuburaya used their own successes to gain independence from the studio system, Honda remained committed to it and accepted the constraints placed on his work and career.

———

“I’ve always felt that films should have a specific form,” Honda said. “Cinema should be entertaining, and should give much visual enjoyment to the public. Many things can be expressed by literature or painting, but cinema has a particular advantage in its visual aspect. I try to express things in film that other arts cannot approach….

“My monster films have met with a great commercial success in Japan and elsewhere [but] that doesn’t mean I’m strictly limited to this type of film. I think I make too many monster films, but that’s because of the direction of Toho.”6

In this excerpt from a 1968 interview, Honda indicated his simple and unaffected philosophy toward film, but also hinted that his creativity was stifled by the studio’s business strategy. Despite his statement to the contrary, by this time Honda was exclusively making monster movies, a source of frustration largely responsible for his eventual departure from Toho. It was Honda’s personality—a quiet and gentle spirit, a self-effacing and selfless tendency to put the needs of others before his own, a desire to create harmony and avoid conflict, and his strong sense of loyalty—that enabled him to thrive under the Toho system, within the parameters set by the company. Honda’s reserved nature was a great asset, the reason he was so beloved by colleagues, but also a liability.

While Kurosawa reinterpreted Shakespeare and Dostoevsky in a postwar Japanese context, Honda was similarly inspired by Merian C. Cooper’s King Kong (1933), George Pal’s War of the Worlds (1953)—two films he frequently cited as influences—and the productions of Walt Disney to create his world of tragedy and fantasy, resembling the Hollywood prototypes but distinctly Japanese in viewpoint. Honda considered himself an entertainment filmmaker, and he admired fellow travelers; in later years, he would prefer the works of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. He was unabashedly populist, putting the viewer’s experience before his agenda behind the camera.

“No matter how artistic a film can be, if no one can appreciate it, it is no good,” he said late in life. “Maybe that was my weak point, that I never thought that pursuing my theme was absolute. That is the way I live. I was never actually in the position where I could say or push my idea on everybody … like, ‘No matter who says what, this is my movie.’ After all, I grew up in the film studio system … I had to make my movies in that system. That’s one reason why I wasn’t completely strict about my theme, but at least I tried to show what I wanted to say, as best I could under the circumstances.

“I have a really strong [connection] with the audience. It’s not about treating the audience just as my customer … I always thought about how [I could make them] feel what I was thinking about. I always tried to be very honest with myself. I tried to show my feelings directly and have the audience feel my excitement. That’s how I tried to make my films.”7

Honda’s loyalty showed in many aspects of life. He remained loyal to his country even when war pulled him away from the job he loved, and even when he was unfairly, unofficially punished for an act of treason with which he had no involvement and was forced to serve much longer than usual. He was a reluctant soldier who avoided fighting unless necessary, but he carried out his duties, motivated to survive the war and return to his family and his work. He remained loyal to the studio even when it nearly fell apart, while others were revolting and defecting, and while younger men were promoted before him. He resolved to continue making feature films even as colleagues joined the rise of television. And he stayed with the studio even after it pigeonholed him as a sci-fi man.

Still, he wasn’t the stereotypical Japanese employee blindly serving his company. Honda saw the director’s role as a collaborative one, as a team leader rather than an author. “There is a great deal of discussion during the writing of the script,” he said. “But once filming starts, the discussions are ended. Once I became part of Toho, I no longer had reason to complain [to] my employer. One may have objections before joining a company, but once you are inside, you really cannot. That is my opinion. [But] if I have the least objection to a script, I certainly do not make the film.”8

———

With hindsight, Honda would express misgivings about his place in the film hierarchy. “The best way to make a film is … how Chaplin did,” he said, after retiring. “You have your own money, you direct, and act and cast it by yourself. That is a real moviemaker. [People] like us, we get money from the company and make whatever film they want. Well, that is not quite a real moviemaker.”9

For Honda’s generation, the studio was the only path to directing. It wasn’t until the late 1940s that Kurosawa and a handful of directors would begin to challenge the status quo and pave the way for independent cinema to come later. And it’s not difficult to understand Honda’s allegiance to the system, for he entered Toho during the 1930s, when by one measure, film output, the Japanese movie business was the biggest in the world, a position it would regain during the 1950s and 1960s, coinciding with the peak of Honda’s career. Japan’s system was modeled after Hollywood, with each studio cultivating its own contracted stars, directors, and writers, and building audience loyalty by focusing on key genres. Just as Warner Bros. became famous for gangster pictures, or MGM for musicals, Toho became known for big war epics during the 1930s and 1940s, and later it would excel in white-collar comedies, lavish musicals, film noir-type thrillers, women’s dramas—and science fiction films, most directed by Honda. Japan’s apprenticeship program was, by some accounts, better than Hollywood’s, with fledgling directors being assigned a mentor, who taught them the techniques of the craft and the politics of the business. Each studio was a tight-knit family of highly talented creative types.

Inuhiko Yomota, perhaps Japan’s most highly respected film historian, believes Honda was “regarded as an artisan filmmaker capable of making various types of movies ranging from highbrow films to ‘teen pics’ within the restrictions of the Japanese studio system.” Honda was among those studio-based directors who did not possess the truly individualistic style of an auteur, yet succeeded because of their ability to use genre conventions as guidelines to be embellished and blended, rather than strict rules. To that end, Honda improvised: Mothra is part fantasy, King Kong vs. Godzilla incorporates salaryman comedy, Atragon contrasts a lost-civilization fantasy with Japan’s lost wartime empire, The H-Man combines monsters with gangsters, All Monsters Attack turns its genre inside out, and so on. Often the theme was a reflection of Honda himself. He would describe making films as the culmination of a lifelong process of observing and studying the world around him. “Only if you have your own [point-of-view] can you see things when you direct or create something,” he would say. “Seeing things through my own eyes, making films, and living my life in my own way … I try to gradually create the new me. That is what it is all about.”10

———

Honda’s personality was evident in his approach to filmmaking and in his self-assessment. In a preface to a memoir published posthumously, he wrote, “Ishiro Honda, the individual, is nothing amusing or interesting. He is really just an ordinary, regular old person and a regular movie fan.” In the same text, he said, “I am probably a filmmaker who least looks like one.” And still later, he described himself as “A weed in the flower garden … Never the main flower.” He preferred not to command the spotlight, but to be noticed for his achievements. “People who come to see the main flower will notice [me]. ‘Hmm, look at this flower here.’”

In outlining his directing philosophy, Honda emphasized collaboration and cooperation. “The most hated word is ‘fight,’” he said. Dialogue and understanding were keys to successful filmmaking: “Talk to each other. That’s the way to get an agreement.”

Like Kurosawa, Ingmar Bergman, and John Ford, Honda had his de facto stock company of performers, many of whom called themselves the “Honda family.” There were major Toho actors such as Ryo Ikebe and Akira Takarada, and sirens such as Kumi Mizuno, Mie Hama, and Akiko Wakabayashi, plus a host of character players. They became the faces of Honda’s body of work, appearing in both genre and nongenre films. Without exception, they would describe Honda as quiet and even tempered. He rarely coached actors directly about their performance; his direction consisted of subtle course correction rather than instruction.

“Actors have many ‘drawers,’ with many things inside, and he was good at pulling open the exact drawer he needed each time,” said Koji Kajita, Honda’s longtime assistant director. “He always suggested what to do, but he never demanded, so he could pull the best out of each actor. I’m sure the actors have no memories of being yelled at or anything like that. That wasn’t his way.

“The biggest thing for him was how to maintain the concept that he had for the script,” Kajita continued. “He had this concept in his head, and when the filming would start to stray from it, he didn’t yell. Instead he very calmly spoke up. It was very firm.

“He had his own style, this way of thinking … he never got mad, didn’t rush, but he still expressed his thoughts and made it clear when something was different from what he wanted, and he corrected things quietly. He persevered. That was his style. I was with him for seventeen films, and I never saw him get mad. His facial expression and manner was gentle and calm … He was that kind of director … He made each film as he wanted, like rolling the actors around in the palm of his hand.”

“[Honda] never forced anything on the actors,” said actor Hiroshi Koizumi. “If there was something he didn’t like or that needed to be changed, he had this soft manner to let us know what he really wanted. He didn’t like it when there was a prearranged result … he always wanted to discuss things and then decide how to do something.”

To those who worked for him, he was Honda-san—literally, Mr. Honda; to those who knew him well, he was the more familiar Ino-san (derived from inoshishi, the first Kanji in his name), or Honda-kun. Whether on the film set, out in public, or at home, he treated everyone as equals, just as his mentor Kajiro Yamamoto had taught him.

“Everything I do is based on humanism, or love towards people,” Honda would say. “My way of life is all about love towards people. I look at others that way … what is their idea of human love? When I make films, it is the same thing …

“Making people obey me is not my idea [of directing]. The entire staff understands what we are doing, and they direct all their energy and skill towards the screen. The director should put all those people together … that is how a good film [is made]. I really believe that my Honda group had lots of fun, always. When people have fun, they enjoy their work. When they enjoy their work … they try their best. I think my workplace was always that way. Maybe each person had personal likes and dislikes each time, but once the camera started rolling, everybody tried their best. There may be some other directors who have a really strong personality and show that through their films … That’s why all movies come out differently … That’s the process of creation.”11

———

Susan Sontag’s 1965 essay “The Imagination of Disaster” brought science fiction cinema to the intellectual fore, and was one of the first American writings to critique Honda’s body of work in a serious manner. Sontag wrote, “Science fiction films are not about science. They are about disaster, which is one of the oldest subjects of art. In science fiction films disaster is rarely viewed intensively; it is always extensive. It is a matter of quantity and ingenuity. If you will, it is a question of scale. But the scale, particularly in the widescreen color films (of which the ones by the Japanese director Inoshiro [sic] Honda and the American director George Pal are technically the most convincing and visually the most exciting), does raise the matter to another level.”12

In surveying the genre, Sontag identified recurring motifs, citing Rodan, The Mysterians and Battle in Outer Space as displays of “the aesthetics of destruction, with the peculiar beauties to be found in wreaking havoc [that are] the core of a good science fiction film.” Sontag also noted themes that Honda’s work shares with American genre films of the period: concern about the ethical pursuit of science; radiation casualties and mutations resulting from nuclear testing; moral oversimplification; a “U.N. fantasy” of united international warfare, with science as “the great unifier”; war imagery; and the depiction of mass destruction from an external and impersonal point of view, showing the audience the thrilling awe of cities crumbling but not the death and suffering that result.

Sontag failed, however, to detect the culturally specific subtleties that separate Japanese science fiction films, informed by the atomic bombings, from American ones, influenced by fears of nuclear war with the Soviet Union. Perhaps the lone Western scholar to define this difference was Donald Richie, the distinguished historian of Japanese cinema, who saw Godzilla, Rodan, et al., not simply as a Cold War–era phenomenon but part of a unique film cycle that expressed the prevailing national attitude regarding the bomb in the 1950s: a lamentation for the tragedy of Hiroshima, an acceptance of its inevitability, and an awareness that the sense of melancholy would pass. Richie identified this feeling as mono no aware (roughly translated as “sympathetic sadness”).

Richie wrote, “This is the authentic Japanese attitude toward death and disaster … which the West has never understood. The bomb, like the war, like death itself, was something over which no one had any control; something which could not be helped; what we mean by an ‘act of God.’ The Japanese, in moments of stress if not habitually, regard life as the period of complete insecurity that it is; and the truth of this observation is graphically illustrated in a land yearly ravaged by typhoons, a country where the very earth quakes daily. The bomb, at first, was thought of as just another catastrophe in a land already overwhelmed with them.”13

Richie’s analogy helps explain why the arrival of Godzilla, Honda’s monster manifestation of the bomb, resembles both a war and one of Japan’s extreme weather events; indeed, when it first comes ashore, Godzilla is obscured by a fierce storm. No one questions why the monster attacks Tokyo, though it has no apparent purpose other than destruction, nor why it returns again, just as typhoons predictably hit Japan’s capital every summer. It also explains why people respond as they would to a natural disaster. An electrical barrier is built around the city, like sandbags against a flood, and citizens seek safety at high ground, as if fleeing a tsunami. Similarly, Rodan creates a metaphorical hurricane, and the Mysterians cause a giant forest fire and landslide. Sometimes, like a sudden earthquake, Honda’s monsters disrupt the humdrum of everyday life: Godzilla’s footfalls come while a family idly passes time in the living room, a giant insect bursts into a home and frightens a young mother, or a woman taking a bath spies a giant robot outside the window.

For Honda, the monsters’ suggestion of natural disaster was also rooted in things he witnessed on the battlefront. “During the war, the Chinese people did not run away when there was shooting between soldiers near their fields,” Honda said. “To them, we were just like a storm. They thought of us as [like] a natural disaster, otherwise they would not have continued living there in such a dangerous place … For me, the monsters were like that. Just [like] a natural disaster.”14

———

“I am responsible for tying Honda to special effects movies,” producer Tomoyuki Tanaka once confessed. “If I hadn’t, he might have become a director just like [Mikio] Naruse.”15

Like the respected Naruse, and like all fine directors, Honda made films chronicling his time and place. Postwar Japan was a crucible of social, political, and economic change, as the veneer of Westernization continued to obscure centuries-old culture. Honda’s early work followed what scholar Joan Mellen calls “the major theme in Japanese films … the struggle between one’s duty and the individual desire to be independent and free of traditional values.” His protagonists were young people, torn between their parents’ ideals and their own, and the conflict often centered on an arranged but unwanted marriage. During the second half of the 1950s, Honda was groomed as a specialist in women’s stories, and made a number of films about independent-minded young women and their changing roles at home and at work. Honda’s handful of women’s films, like Naruse’s, question Japan’s gender norms and depict female passions and disappointments; but Honda’s world is a far more hopeful place, his characters less tragic. Honda had apprenticed with Naruse briefly and admired Naruse’s “sturdy rhythm” and talent for “[showing] people’s thinking in very special, quiet times.” Honda didn’t believe he was directly influenced by the melodramatic Naruse style, but acknowledged, “I had the same kind of things in me.”16

Some of Honda’s recurring themes and motifs were evident even before Godzilla. For instance, The Skin of the South offers images of a natural disaster and the destruction of a town, and presents a scientist as the trustworthy authority in a crisis and a greedy villain exploiter of indigenous people and the environment, two frequent Honda archetypes. From The Blue Pearl through Terror of Mechagodzilla, his last feature, and many times in between, Honda’s drama hinged on a character’s sacrificial death, self-inflicted or otherwise, to restore honor, save others from harm, express deep love, or a combination thereof. Japan’s beautiful and dangerous seas and mountains served as visual and thematic symbols of nature’s power from the very beginning; a mountain boy himself, and an avid hiker, Honda would frequently show a sort of reverence for Japan’s majestic bluffs by having his characters trekking uphill, a visual motif reappearing in numerous films. And throughout his filmography, Honda utilized regional locations, culture, and minutiae to enhance authenticity, from local pearl divers and Shinto ceremony dancers in Godzilla to the obon festival signs written in reverse script, as per regional custom, in The Mysterians. Honda’s preference for a trio of protagonists—sometimes a love triangle, often just three friends—was also there from the first.

The uneasy postwar Japan-US alliance underlies many of Honda’s science fiction films, and while Godzilla and especially Mothra might be interpreted as somewhat anti-American, Honda was increasingly optimistic about the relationship. In his idealized world, America and the “new Switzerland” of Japan are leaders of a broad, United Nations–based coalition reliant on science and technology to protect mankind. Scientists are highly influential, while politicians are ineffective or invisible. The Japan Self-Defense Forces bravely defend the homeland and employ glorified, high-tech hardware; but military operations often fail, and force alone rarely repels the threat. Assistance comes from monsters, a deus ex machina, or human ingenuity. Honda was also frequently concerned with the dehumanizing effects of technology, greed, or totalitarianism.

Honda relied on his cinematographers and art directors to create the look of his films; thus the noirish style of Godzilla, made with a crew borrowed from Mikio Naruse, is completely unlike the larger-than-life look of the sci-fi films shot in color and scope just a few years later by Honda’s longtime cameraman Hajime Koizumi. He was less concerned with visual aesthetics than with theme and entertainment. Therefore, in analyzing Honda’s work, the authors weight these and other story-related criteria, such as tone, characterization, actors’ performances, editing (under the Toho system, editors executed cuts as instructed by the director), pacing, structure, use of soundtrack music, and so on, more heavily than technique or composition. The magnificent special effects of Eiji Tsuburaya are discussed in this same context; detailed information about Tsuburaya’s techniques is available from other sources.17

Honda believed in simplicity of theme. “Yama-san [Kajiro Yamamoto] always used to say … the theme of a story must be something that can be precisely described in three clean sentences,” Honda said. “And it must be a story that has a very clear statement to make. [If] you must go on and on explaining who goes where and does what [it] will not be entertaining. This, for me, is a golden rule.”

———

Research for this project was conducted over a four-year period and included interviews conducted in Japan with Honda’s family and colleagues; archival discovery of documents, including Honda’s annotated scripts and other papers, studio memorandums, Japanese newspaper and magazine clippings dating to the 1950s, and other materials; consultation of numerous Japanese- and English-language publications, including scholarly and trade books on film, history, and culture; consulting previously published and unpublished writings by and interviews with Honda; locating and viewing Honda’s filmography, including the non–science fiction films, the great majority of which are unavailable commercially; and translation of large volumes of Japanese-language materials into English for study.

Only the original, Japanese-language editions of Honda’s films are studied here, as they best represent the director’s intent and achievement. As of this writing, all of Honda’s science fiction films are commercially available in the United States via one or more home video platforms, in Japanese with English-language subtitles, except for Half Human, The Human Vapor, Gorath, King Kong vs. Godzilla, and King Kong Escapes. For these films, the authors viewed official Japanese video releases when possible, and the dialogue was translated for research purposes.18 Honda’s dramatic and documentary films were another matter. To date, only three, Eagle of the Pacific, Farewell Rabaul, and Come Marry Me, have been released on home video in Japan, and no subtitled editions are available. Many others, however, have been broadcast on Japanese cable television over the past decade-plus; and with the assistance of Honda’s family and research associate Shinsuke Nakajima, the authors obtained and viewed Honda’s entire filmography except for two films, the documentary Story of a Co-op, of which there are no known extant elements, and the independent feature Night School; in writing about these two films the authors referred to archival materials and published and unpublished synopses. Yuuko Honda-Yun performed the massive undertaking of translating film dialogue for study. (As this book went to press, it was announced that the rarely seen Night School would be issued on DVD in Japan in 2017.)

Though none of Honda’s non-sci-fi films are currently available in the West, they are analyzed in this volume—admittedly, to an unusual and perhaps unprecedented extent—because they reveal an invaluable and previously impossible picture of the filmmaker and the scope of his abilities and interests, exploring themes and ideas that his genre films often only hint at. And with the advent of streaming media and new channels for distributing foreign films, it seems not unlikely that some of these rare Honda pictures will appear in the West before long.

One pivotal part of Honda’s life that remains mysterious is his period of military service. Honda rarely spoke openly about his experiences, but it is clear that multiple tours of duty and captivity as a POW left psychological scars and informed the antiwar stance of Godzilla and other films. “Without that war experience, I don’t think I would be who I am,” Honda once said. “I would have been so much different had I not experienced it.”19

Honda had collected his war mementos, such as correspondence, diaries, documents, and artifacts, in a trunk that was locked away for the rest of his life. It was his intention to return to this trunk and assemble the material in a memoir, a task never completed. Sources for the account of Honda’s military service in this book were limited to Honda’s writings, interviews with family members, and other secondary materials. The Honda family has decided that the contents of the trunk should remain private. A small number of the trunk’s materials were shown in a 2013 NHK television documentary and subsequently put on limited public display in a museum exhibit. However, the contents have not been archived and made available for research; thus, it is unknown what further details may eventually come to light about Honda’s lost years at war.

———

The book concludes with the first detailed chronicle of Honda’s third career phase, in which he reunited and collaborated with Akira Kurosawa. Beginning with the production of Kagemusha (1980) through Kurosawa’s last film, Madadayo (1993), this period was a rejuvenating denouement for both men, a return to the free spirit of their early days as idealistic Toho upstarts, with Honda rediscovering his love of filmmaking while providing a bedrock of support for “The Emperor,” his oldest and closest friend.

It is a little-known fact that Kurosawa once ranked Godzilla number thirty-four on his list of one hundred favorite films, higher than acclaimed works by Ozu, Ford, Capra, Hawks, Fellini, Truffaut, Bergman, Antonioni, and others. In doing so, Kurosawa wrote: “Honda-san is really an earnest, nice fellow. Imagine … what you would do if a monster like Godzilla emerged. Normally one would forget everything, abandon his duty, and simply flee. Wouldn’t you? But the [authorities] in this movie properly and sincerely lead people [to safety], don’t they? That is typical of Honda-san. I love it. Well, he was my best friend. As you know, I am a pretty obstinate and demanding person. Thus, the fact that I never had problems with him was due to his [good-natured] personality.”20

Honda’s story is about a filmmaker whose quietude harbored visions of war and the wrath of Godzilla, whose achievements were largely unrecognized, and whose thrilling world of monsters was both his cross to bear and his enduring triumph.

“It is my regret that I couldn’t make a film that I would consider [the greatest] of my life,” Honda said. “Each time I did my best, so for that I have no regret. But when I see my films later, there is always a spot where I feel like I should have done it this way, or I should have stood up for myself against the company. I do regret that.

“[However] it was definitely my pleasure that I was able to make something that people can remember … If I had not made Godzilla or The Mysterians, even if I would have received some kind of [critical] prize, it wouldn’t be the same. There is nothing like the happiness I get from those things.”21

NOTES ON THE TEXT

For familiarity and ease of reading, Japanese names are printed in the Western manner, with the subject’s given name followed by the surname, e.g., “Ishiro Honda” rather than “Honda Ishiro.” Macrons (diacritical marks) are not utilized in the text.

Foreign films are referenced by their official English-language title at the time of this book’s publication. This may be different from the title under which a film was originally released in English-language territories. For films with no official English title, a translation of the Japanese title is given.

For Ishiro Honda’s films, the original Japanese-language titles and their translations, if different from the English titles, are provided in the filmography following the text. For other films, the English title or translation is followed by the native-language title in parentheses on first reference in the text.

Japanese terms are presented in italics, followed by their English meaning in parentheses. Terms familiar to Western readers, such as anime, kabuki, manga, and samurai, are not italicized.