Читать книгу Ishiro Honda - Steve Ryfle - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление10

SEA, LAND, AND SKY

The Blue Pearl (1951), The Skin of the South (1952), The Man Who Came to Port (1952), Adolesence Part 2 (1953), Eagle of the Pacific (1953), Farewell Rabaul (1954)

The area of Ise Peninsula is land that sunk into ocean and later resurfaced. Because of this, there are mountains that come right up to the shorelines. About 85 percent of the land is mountainous or wasteland, and only the remaining 15 percent or so is suitable for agriculture. This is not nearly enough for the people to maintain economic stability, so the special occupation of the ama divers came into being naturally, out of necessity. Most of the workers are female, so the men born on the [peninsula] are sent away, with the exception of first-born sons. The girls start their training in the ocean from about 11 or 12, become fully trained by 16 or 17, and will continue to work in the sea until about 60. They dive into the ocean and harvest abalone, sazae (a type of conch) and gelidiaceae (a type of algae). Pearl oysters are harvested for a limited time each year, the best time being usually a week or so in mid-May. Single ladies dive individually and married ladies dive with a lifeline tied to them, which is connected to a pulley and handled by their spouse. The wives dive down to the ocean floor holding a 15-kilogram weight. Their methods are quite primitive, their living standards are quite low, and there are many myths and legends that they believe in. However, all of these things fit their lifestyle well … They do not use modernized harvesting methods, diving suits or equipment because this would cause their profession to become obsolete … Everything is unwittingly and naturally adapted.

In a poor village with such traditions and culture and an unnatural society where women hold financial power, there is a certain need for traditional conventions to take control and for the people to be content with such ways. These women are born into such dreary living conditions; I wanted to incorporate these elements as the basis of the film and capture their reality.

— From “Ama,” an essay by Ishiro Honda (1951)

Japanese culture has clashed with Western values ever since Commodore Matthew Perry made his uninvited visit in 1853 and pried open the nation’s ports and markets to the world, a clash intensified by the Occupation’s assault on customs and traditions. Honda’s romantic tragedy The Blue Pearl, at first glance, appears to follow the democratization standards proscribed by the American censors: open criticism of old superstitions, assertive and independent female characters, and affection between the two leads. At the same time, in depicting a traditional way of life suddenly threatened by outside influence, The Blue Pearl mirrors the occupied Japan of its day. These themes and ideas reflected Honda’s own worldview, and they would recur in his films well after the Occupation. Upon its release, this remarkable little film was praised for its promising director’s auspicious debut and for introducing underwater photography to Japanese cinema, but over the decades it has become forgotten, a lost gem.

The Blue Pearl was partly inspired by Honda’s experiences filming the documentary Ise-Shima. He admired the people he’d met, felt the coastal scenery of Mie Prefecture was an ideal setting for a dramatic film, and wanted to shoot underwater again. The project was suggested by Sojiro Motoki, a close friend of Honda and Kurosawa since the Toho days and a driving force behind the Film Art Association. Motoki was now working for Toho and considered the Japanese film industry’s leading producer.1 Motoki had found an ideal story: Ruins of the Sea (Umi no haien), a 1949 Naoki Prize–winning novella about pearl divers written by seafaring author Katsuro Yamada. Honda decided to adapt it for the screen, and in 1950 he and Akira Kurosawa left Tokyo for a writing retreat at an inn in Atami, a popular hot spring resort.2 While Honda wrote The Blue Pearl, Kurosawa adapted Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s acclaimed 1922 short story “In a Grove” (Yabu no Naka), which became Rashomon.

“I wanted to do a film with underwater scenes, and this story just happened to be there,” Honda later said. “I wanted to show the relationship between nature and humans through these ama [who survive by diving for abalone]. I thought this would lead to a new field of movies that featured undersea scenes.”

The two men would begin writing at 9:00 a.m. daily, sitting at adjacent desks. After each had completed about twenty pages, they’d exchange drafts and critique one another’s work. Honda would later recall that, within just a few days, Kurosawa disagreed with certain aspects of Honda’s script, and “after that he decided not to read mine any more. Of course he still made me read his.”3 Ultimately, though, Kurosawa gave Honda’s work a thumbs-up. Honda said, “When I finished writing the screenplay, I could not hold back [the excitement] so I immediately went to see Kurosawa. He was sleeping, but he read through it at once, still lying down. And then he tapped my shoulder. That really moved me. I could not help the tears coming out of me.”4

After the men had finished writing, producer Motoki pitched The Blue Pearl to Toho and received approval right away; it was one of about twenty-seven features produced by the resurgent studio in 1951. Around the same time, Motoki proposed Rashomon to Daiei Studios’ president Masaichi Nagata, who at first turned that project down, predicting a flop. The irony, of course, is that decades later The Blue Pearl is a footnote in Japanese cinema, while Rashomon is indisputably one of the great films of all time.

Honda spent considerable preproduction time hunting locations and conducting research in the Ise-Shima area. “I had written the first draft of the script and the project was officially given the green light,” he recalled. “[Toho] gave me about three months to just go around the area [location scouting] from one place to the next. They allowed us to do such things [because of the poststrike slowdown], although in a way, this should be the norm. So once we started filming, there were no moments of hesitation, we were able to just keep moving forward.”5 Honda became a familiar face to the locals, who shared stories and granted him access not usually afforded to outsiders.

———

This verse appears onscreen after the opening credits of The Blue Pearl:

Ama divers and pearls

Ise-Shima, washed by the Japan Current

Hidden here are several tragic stories

About the lives of the ama divers and pearls

Set in a rustic, seaside village, The Blue Pearl is about a young diver, Noe (Yukiko Shimazaki, later of Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai), who falls in love with the town’s new lighthouse attendant and schoolteacher, Nishida (Ryo Ikebe), freshly transplanted from Tokyo. Nishida’s arrival, and his outsider ways—he dresses in city clothes, is a gifted artist, has no patience for superstitions and feudal traditions, and smokes citified cigarettes—stir Noe’s desire to leave behind an unwanted arranged marriage and a hard life of diving. The couple is scorned by the locals and split apart by the meddlesome Riu (Yuriko Hamada), a flirtatious ex-ama diver. Riu returns from two years in occupied Tokyo as a changed, liberated woman wearing American clothes, sunglasses, a primped face, and painted nails.

The film’s second half is both physically and psychologically darker, as rains pelt the coast and Noe’s happiness turns to torment. Noe’s parents forbid her to see Nishida, and Riu attempts to seduce him in Noe’s absence, spreading rumors that she’s carrying Nishida’s bastard child. The two women settle the score by diving to retrieve the legendary pearl of the Dai nichi ido well. Folklore says the pearl brings true love, but the locals fear the gem is cursed and should be left untouched. At the sea bottom, Riu reaches for the pearl, but her hand is caught in the rocks and she drowns, while Noe nearly dies trying to save her. Guilt-ridden, scorned by villagers who believe she killed her nemesis, and haunted by the ghostly cries of Riu calling from the sea, a distraught Noe walks alone on the moonlit sand. The film concludes as Noe wades into the waves, following the disembodied, haunting voice to her death.

Honda’s screenplay differed from the original novella in a few significant ways. Honda made the main character, Noe, more sympathetic by omitting an abortion and a scene where she attempts to stab archrival Riu to death underwater. He added the legend of the pearl and the sacred well and other local folklore, much of which he learned during his location-hunting tour of the area.

Honda recalled adapting the story: “Legend has it that whenever an ama gets too close to [the Dai nichi ido well], she dies. This well is all that remains after an old shrine sank underwater a long time ago. The ama divers fear this legend, and unless there is a significant reward, they will not dare go near it. Also, it is not permitted for them to wed outsiders. This is because the ama support the local economy, and the entire village would suffer if they left.”6

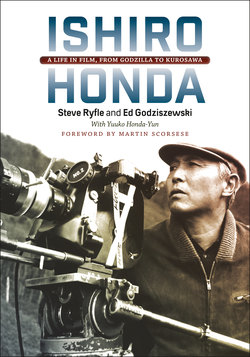

Directing native ama divers as extras in The Blue Pearl.Courtesy of Honda Film Inc.

The Blue Pearl introduces themes Honda would revisit often in his non–science fiction films, chiefly that of the outsider who challenges the status quo. Nishida’s arrival in the little village triggers conflicts mirroring Japan’s universal postwar identity crises: old traditions versus modern thinking; doubts about arranged marriage and feudalistic customs; a generational gulf between conservative adults and liberated youths; the emergence of assertive, independent-minded women; pastoral virtue versus urban decay. Casting its shadow over all is Japan’s class structure, officially abolished by the Meiji government in 1873, but still the unspoken rule. Its obligations are understood, its rules unbendable. The ama divers are expected to support the village through a lifetime of hard labor. Noe and Riu, who dream of leaving the bubble, both pay with their lives.

———

Since the 1890s, Japan has been harvesting its world-renowned pearls, three-quarters of which are still collected by the women divers of Ise-Shima. Honda provides a window into the daily life and culture of the ama: their daily chatter and gossiping, their friendly competition to collect the most oysters, and the rigors and routines of their work. But the most intimate moments of ama life are captured during the underwater sequences, when all the chattering stops and the women are truly in their element. Cinematographer Tadashi Iimura records the balletic athleticism of the dives, performed by actual divers with the underwater camera system created for Ise-Shima, this time with longer takes and more camera agility.

This image has been redacted from the digital edition. Please refer to the print edition to see the image.

The Blue Pearl. © Toho Co., Ltd.

Because The Blue Pearl was promoted as Japan’s first feature film with underwater photography, journalists were on location to document the logistical challenges. A writer for Lucky magazine described the filming of the climactic underwater conflict between the divers:

“[Cameraman] Iimura … all dressed up in his diving gear, puts a portable camera into a metallic body that acts as a special waterproofing device. With it under his arms, he dives into the water from the pontoon. [Honda] and his assistant director both watch from the boat using glass scopes. There are two professional divers underwater to assist the cameraman. The battling Riu and Noe are of course real ama divers, doubling for the actresses.”

Because of a miscommunication between the cameraman and the crew in the boat, Iimura was mistakenly pulled out of the water before the shot was finished.

“[To avoid repeating this mistake] … they created ‘underwater telegramming.’ [Honda] writes on Kent paper in red pencil, ‘shoot towards the right,’ and an ama takes that and dives underwater. Upon receiving the message, the cameraman waves towards the water’s surface, signaling, ‘Roger.’ This is how filming continued smoothly.”7

The Blue Pearl shows Honda striving for a balance between a documentarian’s desire for authenticity and a storyteller’s need to connect emotionally. In an early scene, Honda incorporates formal documentary technique as Fujiki (Takashi Shimura), the elder lighthouse man, explains the life and culture of the ama for the benefit of newcomer Nishida and, by extension, for the audience. Over a montage of ama plunging into the sea, Shimura’s narration describes kachido style diving, in which young women dive from the shoreline and work in groups, and funedo style, wherein more experienced ama dive from boats to greater depths, working with a male partner, usually a husband, who pulls them to safety if danger arises. Honda deftly illustrates one fascinating detail of ama life without ever mentioning it. When the divers surface, a piercing, high-pitched whistle is heard; though unexplained, this is the sound ama make when emptying air from their lungs after a long dive. The documentary approach emphasizes Ise-Shima’s natural beauty, and Honda adds another layer of authenticity by casting local children who speak a regional dialect as Nishida’s pupils and local adults as background extras, and by including a harvest festival with dancers in indigenous costumes.

Even with all its nonfiction-style trappings, The Blue Pearl is a melodrama and Honda does not hesitate to use sound, imagery, and a brilliant score by Tadashi Hattori, one of Japanese cinema’s more prolific composers, to punctuate emotion. The director’s inexperience is betrayed when Noe and Nishida declare their love during a raging rainstorm, an overused cinematic and literary harbinger of doom. In a moment taken from Yamada’s novella, a bird slams into the lighthouse window and dies, telegraphing the lovers’ fate.

Other moments are more effective, particularly the race to find the legendary pearl at the sea bottom. Then there is the final, haunting scene, as Noe walks along the beach with the moon and stars illuminating the rocky shore and the water’s glistening surface, achieved with effective day-for-night photography. Led by the distant, imagined cry of Riu’s voice, Noe sheds her robe and wanders into the surf, surrendering to the god of the ocean as a choral requiem swells and a lighthouse beam scans the night. Several of Honda’s early films would reach an emotional climax with a suicide or self-sacrifice, and Noe’s tragedy is among the most heartrending. Interestingly, Honda and editor Koichi Iwashita—the man who had introduced Honda to his wife some years earlier—strongly disagreed about the suicide scene, which was longer in Honda’s original cut. Iwashita had seniority over the new director and insisted on shortening the ending, despite Honda’s objections that the audience would be confused.8 And in fact, some reviewers complained that Noe’s death scene was ambiguous. Honda recalled feeling “upset, frustrated, and bitter resentment.”9

Even if he was not a demonstrably spiritual man, The Blue Pearl reveals Honda’s knowledge of Shinto, the indigenous religion with ties to Japanese values and history. A core belief is that all natural phenomena—people, mountains, trees, the ocean, and so on—are inhabited by kami (gods), thus deference to nature and the environment are of utmost importance. The Blue Pearl’s elder villagers speak of Ryujin-sama, their sea god, warning the younger generation to respect the ocean and maintain their traditional way of life. Noe and the other ama pay respects and cleanse their spirits in water-purification rituals, a Shinto practice, to appease Ryujin-sama and bring a healthy pearl harvest. Still, Honda straddles a delicate line between criticizing and defending feudalistic customs. Nishida openly mocks the old superstitions, saying their true purpose is to preserve the local way of life by instilling the ama divers with a sense of obligation. “You shouldn’t mock the sea,” Noe warns him. “Leave the ocean alone.”

Honda (far left) with actresses Yukiko Shimazaki and Yuriko Hamada, and cameraman Tadashi Iimura, on location for The Blue Pearl.Courtesy of Honda Film Inc.

Performances by the cast of veterans and newcomers are inconsistent, on account of both Honda’s inexperience with actors and his hands-off approach to directing them. The standout is Shimazaki, who essentially gives two performances. In the first half of the film, Noe is radiant and full of life as she falls for Nishida; in the second half, she is distraught and inconsolable as the lovers are scorned and separated. Shimazaki was a relative newcomer, while leading man Ryo Ikebe, in his early thirties, was an established Toho heartthrob with throngs of female fans, box-office appeal, and the ability to play men younger than himself. Ikebe initially joined Toho as a screenwriter trainee but switched to acting at age twenty-three; and during the 1940s and 1950s, he worked with many of Japan’s best directors, such as Naruse, Sugie, Ichikawa, and Toyoda. Honda would get better results from Ikebe later in An Echo Calls You (1959), but here the actor lacks charisma, especially compared to the seemingly effortless performance of Shimura, with whom he shares several scenes. Shimura was already a fixture in Akira Kurosawa’s company, playing the woodcutter in Rashomon and the alcoholic doctor in Drunken Angel. He would now also become an occasional yet supremely important member of the nascent Honda family of actors. Hamada plays Riu without much subtlety, as a cackling, brash femme fatale who chews ample scenery.

Prior to its August 3, 1951, release, The Blue Pearl was welcomed by a trio of familiar well-wishers. A Toho Studios newsletter featured testimonials from Honda’s mentor Yamamoto, as well as the other two members of the Three Crows, Kurosawa and Taniguchi. All were pleased their friend had persevered. “Some people may have had doubts, saying, ‘Honda-kun may not be able to return to work in the film world again,’” wrote Yamamoto. “I must say that the arrival of this newcomer, who is an opposite personality to Kurosawa-kun, is a great asset to the film industry.”

Kurosawa, in his testimonial, said he wasn’t sure what to expect from his friend.

“Ino-san came up under Yama-san, just like Sen-chan and I did,” Kurosawa wrote. “We were like three brothers. And of these three brothers, Ino-san was the quietest. He was always just calmly listening to us debate. That’s why, when we heard that Ino-san was finally striking out on his own, it made both Sen-chan and me a little worried, because we had no idea what Ino-san was thinking. We were clueless about what kind of work he was capable of doing.

“But one day, he paid me a visit and said, ‘I want to do this.’ When he let me read his screenplay, it made me completely happy. We were mere fools for worrying. Ino-san had been quietly and steadily building himself in his own way. And Ino-san’s world is so fresh, pure and innocent. I was so ecstatic and praised him for his work. But all Ino-san said was, ‘Stop, you are [embarrassing me].’ This is the kind of guy Ishiro Honda is.” Taniguchi, meanwhile, took a tongue-in-cheek approach to praising his friend’s debut, likening Honda to an upstart rival who must be eliminated.

The Blue Pearl was one of the first studio feature films shot in the Ise-Shima region, and one of the first to feature actual ama divers.10 Honda would return to the area for the Odo Island sequences in Godzilla and parts of the final battle in Mothra vs. Godzilla.

Reviews were mostly favorable. Much praise was given to the film’s technical merits, not only the breakthroughs in underwater filming but also Iimura’s camera work, the extensive location shooting, and strides in sound recording. Like Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950), The Blue Pearl featured extensive dialogue recording on location, reducing the need for postdubbing; one reviewer called it “a test case for audio recording in film.” Many reviewers noted Honda’s long journey to the director’s chair and gave him high marks for an ambitious, if not completely successful film, while looking forward to his next.

“[Honda] is a person with strong moral fiber and determination,” wrote a Nagoya Times critic. “His great technique, a fresh and clean sensibility, and attention to detail are refreshing.”

———

There were stretches during the Occupation when work was infrequent. Honda spent time reconnecting with his family and bonding with his children, particularly Ryuji. Having been away at war when his son was born, Honda had trouble relating to the boy at first, but in time they grew closer. On free days, Honda would take the children, and sometimes their friends too, on outings to the Tama River, where they’d play games on the banks. In those days, the neighborhoods of Tokyo’s Seijo Ward were home to numerous American families. Many of Ryuji and Takako’s friends were American kids, and the Hondas would socialize with their parents. As the family would later recall, there was no talk of the war, no feeling of enemies reconciled—just neighbors.

“There was a family of a high-ranked commissioned officer that lived in Seijo, and I was close friends with their kids,” remembered Ryuji. “They spoke English, and I spoke Japanese; when we’d play together the languages would be mixed up, Japanese and English. Once a month, they brought us a big cardboard box full of Levi’s jeans and T-shirts and Double Bubble gum and chocolates and things. Those families were there to try to communicate with the Japanese.

“And one day, they disappeared. They had left.”

———

When the Occupation officially ended in April 1952, Toho was still recuperating from the devastating effects of the strikes, struggling to regain its footing and produce new films. For this reason, Honda’s second film, The Skin of the South, originated outside the studio system. The film was produced by Saburo Nosaka, who had previously worked for Toho Educational Film Division but left to form an independent outfit, Thursday Productions. Nosaka bankrolled the project with funds from private investors, primarily Shigeru Mizuno, a wealthy paper company owner and ex-member of Japan’s communist party. Nosaka produced the film under his company banner, hired Honda to write and direct it, and struck a distribution agreement with Toho, which desperately needed new product to exhibit in its cinemas. “I accepted this film because the studio was still a mess,” Honda later recalled. Shot mostly on location and outdoors, this film finds the young director again treading the line between nonfiction and fiction, combining documentary elements and a veneration of nature with human drama. The Skin of the South was the first true collaboration, on a small scale, between Honda and special-effects man Tsuburaya, who, working uncredited, created a miniature-scale typhoon destruction sequence for the climax.

Later in his career, when making science fiction films, Honda would often visit scientists at universities, querying them about pseudoscientific concepts in the hope of making his films believable, if not always realistic. Honda did this for the first time during preproduction for The Skin of the South, a story based on geological fact. Honda was inspired by a news magazine article about disasters in the Satsuma Peninsula area of Kagoshima Prefecture, near the southwestern tip of Kyushu, where farmlands cultivated on unstable soil composed of porous volcanic ash were washing away during heavy rains, leaving behind huge craters and valleys. To learn more about the phenomenon, Honda visited the Institute for Science of Labor, a think tank for industrial and agricultural safety issues, where researchers had been investigating the landslides. Honda also went on a fact-finding trip to the region, where he was shown roads and farm fields that had sunken into the earth.

“There was an elderly man who took us around,” Honda remembered. “He said, ‘This land had been in our family for generations.’ We are talking acres and acres. [During a storm], someone came calling for him yelling, ‘Grandpa, it’s crumbling!’ So he immediately ran out to see. What he found was farmland slipping away right in front of his eyes, making a sound like twenty or thirty army tanks driving by. He was in a pure daze, but then ran straight back to the house, grabbed a bottle of sake, and just drank as he watched his land disappear. What a shocking story … I only wished there was something that could have been done to help the situation.”11

In his initial draft, Honda’s geologist hero solved the problem and saved the villagers, a happy ending, but Honda rewrote it after a geologist at Kagoshima University told him no such solution was remotely possible. “We [told] him how we need a happy ending since this is a movie. He made a sad face and said, ‘I am very sorry to have to say this, but there really is nothing that can be done to prevent this occurrence … Frankly, I am a bit troubled you are going to depict this in a movie.’ As a filmmaker, this experience made such a strong impression on me.”12 Honda opted for an ambiguous resolution instead, one showing the area recovering from the tragedy, but offering no assurance that it could not happen again. Indeed, typhoons regularly trigger landsides across Japan; in Kagoshima, a series of typhoons in July and August 1993 caused landslides that killed seventy-one people.

The story follows two university geologists from Tokyo, Kakuzo Ono (Hajime Izu) and Shoichiro Takayama (Shunji Kasuga), researching the soil on a plateau in Kagoshima, where huge swaths of land have been washed away by typhoons, killing two hundred. They are joined by Sadae Miura (Yasuko Fujita), a female doctor conducting a health study on the area’s women. A big logging company plans to revive the local economy by cutting down trees, but Ono, the head researcher, warns that deforesting the mountainside will bring massive landslides when it rains, destroying the village. Greedy lumber baron Nonaka (Yoshio Kosugi) convinces everyone that the scientists are meddlesome outsiders, not to be trusted. The feudalistic town elders reject Ono’s plea to relocate the village to a safer area; logging continues, and Ono becomes despondent. Then one night a downpour comes. The villagers run to higher ground, all except the evil Nonaka. Ono risks his life trying to save the villains as a massive landslide wipes out the village. Two years later, Ono and Sadae visit the graves of two friends killed in the disaster. Livestock graze and crops are growing, a ray of hope.

This is the framework of Honda’s screenplay, which according to some sources was based on Blooming Virgin Soil (Hana aru shojochi), an original story by writer Kiyoto Fukuda. But it’s really just half of the film. Superimposed onto the researchers’ struggle is a soapy love quadrangle involving the three scientists and Keiko (Harue Tone), a mysterious local girl. It is explained that Keiko was sent away to live with a wealthy family as a teenager (a Meiji-era tradition to teach girls manners and etiquette in preparation for marriage) and was sexually assaulted by the family’s son, leaving her traumatized. Meanwhile, Ono is so focused on his work that he fails to notice Sadae is falling hard for him. Soon Sadae’s uncle tries to convince her to quit her job for an arranged marriage with the wealthy Motomura (Ryuzo Okada), but she rebukes her suitor after learning he is the man who raped Keiko years ago. Then there is Ono’s assistant, Takayama, who falls ill halfway through the film, spends much time in bed, and expires while bravely trying to warn others about the impending storm.

With its unusual and beautiful setting and themes of conflict, corruption, love, and destruction, The Skin of the South has the makings of a compelling disaster drama. It flirts with numerous interesting ideas: a professional woman rejecting an arranged marriage, the taboo subject of rape, and the outmoded custom of enslaving prospective wives. These issues are resolved too easily, leaving Ono’s quest to save the villagers from doom as the only plot thread generating conflict and drama. The battle between science and politics, illustrating Honda’s concern about the fate of the environment in Japan’s then emerging capitalist system, comes to a head in a showdown at city hall, a scene foreshadowing present-day debates over climate change. Ono tries to convince officials of the grave danger ahead, but the conniving Nonaka discredits him. “You people keep saying science this, science that, but when exactly will that mountain crumble?” Nonaka says. “If we cut down the trees, will the mountain slide the very next time it rains? Or will it be ten years from now, or even a hundred years from now? How can we spend tens of millions of yen to relocate the village based on what you say you know, but you’re unsure of? Stop with your dreaming. The village is already worried about the upcoming taxes.”

Discussing a scene from The Skin of the South with cast and crew on location.Courtesy of Honda Film Inc.

The two halves of The Skin of the South unspool as separate stories, unevenly weighted. Honda is most interested in the ethical scientists and their pursuit of truth. Considerable time is spent with the geologists as they mundanely collect and sort soil samples. Copious exposition details the area’s history, and Ono repeatedly pleads his case to anyone who will listen. Ono is a precursor to scientists confronting political intransigence in later Honda films, notably Dr. Yamane in Godzilla. Honda’s favored semidocumentary style is evident during the opening credits and sequences showcasing Kiyoe Kawamura’s cinematography of landslide-affected areas, such as a huge crater in the side of a mountain and a field that ends at a sheared cliff. Kawamura, who shot Honda’s Ise-Shima, renders both the Kagoshima beauty (majestic streams, valleys, and lakes) and the threat to it (newsreel-style shots of trees falling) in stunning black and white.

The three main protagonists are all flawless and therefore rather dull. Izu, the nominal leading man, plays Ono as a single-minded square, passionate about soil and little else. However, Kosugi, a great and prolific character actor for Honda, Kurosawa, and others, steals every scene as the gap-toothed, intimidating thug Nonaka. The only A-lister among the cast is Shimura, making a cameo. “Around this time,” Honda remembered, “my films were not so much about the kind of human drama that veteran actors liked to do, so I tended to use new people.”13

Eiji Tsuburaya had left Toho in 1948, ostensibly because of his involvement in national policy films. According to Tsuburaya biographer August Ragone, Occupation authorities concluded that Tsuburaya’s realistic Pearl Harbor miniatures could have been created with only classified information; therefore, they erroneously believed Tsuburaya “must have been part of an espionage ring.”14 Undaunted, Tsuburaya formed an independent company, Tsuburaya Visual Effects Laboratory, and worked for various studios on a freelance basis. He received no screen credit for his work during this period, but several projects are known to bear his handiwork, notably Daiei’s Invisible Man Appears (Tomei ningen arawaru, 1949), one of Japan’s first significant science fiction films. The Skin of the South was produced in the last days of the Occupation, but before those people banished from the studios were allowed to return openly; Tsuburaya’s uncredited involvement has been documented by film historian Hiroshi Takeuchi and others. The landslides during the film’s climax are a preview of the more ambitious disaster scenes Tsuburaya would create in science fiction films years later. There are several brief cutaways to the villagers watching their land wash away, and these appear to be the first-ever scenes combining Tsuburaya’s effects and Honda’s live-action footage.

———

No one influenced the trajectory of Ishiro Honda’s career more than producer Tomoyuki Tanaka. Born into a wealthy Osaka family, Tanaka came from a far different background than Honda; but the two men were close in age and had certain things in common, including the tutelage of studio head Iwao Mori, who had pulled Tanaka from Toho’s literature department and groomed him to be a producer. Tanaka produced a handful of Toho movies before the end of World War II; then, during the Occupation he made the controversial Those Who Make Tomorrow; Senkichi Taniguchi’s debut, Snow Trail; and other projects. In 1948 Tanaka left Toho in protest of the communist purge and spent four years working with the Film Art Association, where he produced the aforementioned Escape at Dawn and other projects. In 1952 Iwao Mori’s banishment by Occupation authorities was over, and Mori returned to Toho, inviting Tanaka to join him. Although in his early forties, Tanaka was still viewed as an up-and-comer. In the years ahead, Tanaka would become one of the studio’s most commercially successful producers through a close alliance with Honda and Tsuburaya, the foundation of which was inconspicuously laid in The Man Who Came to Port (Minato e kita otoko), a film that proved far less than the sum of its substantial parts, including starring turns by Takashi Shimura and Toshiro Mifune.

“This was the film where I met Tomoyuki Tanaka,” Honda later recalled. “We both had the same type of goal … At this time [he] was really a beginner; many of the producers were much older then. [Projects with] big stars were done more by the upper echelon, but younger producers had to explore new genres. Because of this, younger producers and directors and staff were all working together [and] people started noticing the kinds of things I wanted to do.”15

Honda was earning a reputation for his semi-nonfiction style and skill at capturing natural, nonurban settings; so when Tanaka approached the director with a drama about whalers, it seemed an ideal fit. Toho had acquired the book Dance of the Surging Waves (Odore yo Doto) by Shinzo Kajino, a popular writer of maritime fiction, and it had access to more than twenty thousand feet of documentary footage shot by cameramen Hiromitsu Karasawa and Taichi Kankura on actual Japanese whaling expeditions at sea, including a trip to Antarctica.

At the time, Mori was just beginning to reestablish Toho’s special-effects capabilities, and the studio had recently acquired a rear-screen projection system. Shimura and Mifune play captains of competing whaling vessels, and the idea was to use the rear-screen process to combine the documentary footage in the background with shots of the actors firing a harpoon gun on a soundstage, creating the illusion they were on the bow deck of a whaling vessel. Tsuburaya hadn’t perfected the process yet, thus the results were unconvincing and used sparingly. Honda liberally incorporates actual footage of whales breaching, harpoon guns firing, whales flailing as they’re fatally struck, and cetacean carcasses being towed into harbor; he crosscuts these violent, graphic images of the animals being hunted with actors matter-of-factly pretending to hunt them. Compared to the reverence for the ocean and the view into the world of the ama in The Blue Pearl, this film’s surface treatment of the dangerous life of whalers, who spend most of their time on land, drinking sake, is uninspired. There is no romance of the sea, no worshipping of the mighty, godlike creatures pursued across the hemispheres and, aside from a fleeting reference to a “white whale,” no aspirations to Melvillean adventure. The Man Who Came to Port is a compact soap opera in which the two main rivals just happen to be whalers.

Set in a small whaling town on Kinkasan Island in Miyagi Prefecture, the story centers on the gruff veteran Capt. Okabe (Shimura). An expert whale gunner and respected seaman, Okabe values tradition and experience above all, but his beliefs are challenged by the arrival of the outsider Ninuma (Mifune), a young, handsome sailor with an urban air, education, and top whale-gunning skills. Sensing his seafaring days waning, Okabe plans to buy the local inn and settle down for retirement, and hopes the innkeeper’s daughter, the much younger Sonoko (Asami Kuji), will marry him. Sonoko, however, is attracted to Ninuma, who suppresses his own feelings and, out of respect for his captain, encourages her to marry Okabe, creating a complicated triangle of hurt feelings. Soon Ninuma becomes captain of another whaling ship, infuriating Okabe, who feels pushed aside for the younger generation. Complicating matters is a rocky reconciliation between Okabe and his illegitimate son, Shingo (Hiroshi Koizumi). In the climax, Okabe foolishly tries to prove himself by hunting whales in a typhoon, but he goes adrift and Ninuma must rescue him. Now friends, the two former rivals leave for a six-month whaling expedition to Antarctica.

This image has been redacted from the digital edition. Please refer to the print edition to see the image.

The Man Who Came to Port. © Toho Co., Ltd.

Though rarely seen today, The Man Who Came to Port was a significant movie for Toho, one of the first projects completed after the studio fully resumed production in 1952 and began to recover from the disastrous effects of the war, the strikes, and the communist purge. This was an A-class picture, evidenced by the personnel in front of and behind the camera. Shimura and Mifune were by now firmly ensconced in Kurosawa’s fold and committed to his projects first and foremost, sandwiching other films in between. Shimura had just finished starring in Kurosawa’s Ikiru (1952), while Mifune was busy working on a number of films after Kurosawa’s The Idiot (1951) and before Seven Samurai (1954), the film that would make both he and Shimura superstars.

Honda’s direction of the leads is more nuanced than before, as Shimura and Mifune create believably flawed, yet likeable dueling protagonists. Capt. Okabe feels so threatened by young Ninuma’s arrival that he lashes out at his crew when things go wrong, but Shimura also shows the grizzled captain’s other side, a lonely and sensitive older man. While best known in the West for his animalistic fury in Rashomon and Seven Samurai, Mifune in The Man Who Came to Port is typical of the stoic, stalwart heroes he played in studio fare outside Kurosawa’s oeuvre during this phase of his career. As Ninuma hides his emotions, Mifune layers the character with simmering anger that surfaces in drunken outbursts.

By now Toho had a stable of character actors populating the works of most all the studio’s directors. A core group became Honda’s favorites, reappearing in numerous films. The Man Who Came to Port marks the first appearances of two such actors who became very familiar faces: Ren Yamamoto, who would later stand out as a terrified villager in Godzilla, and Senkichi Omura, known for playing excitable working-class types, and later memorable as the goofball interpreter in King Kong vs. Godzilla. The cast also features Kurosawa mainstays, including Bokuzen Hidari, known for portraying sad old men, as the glassy-eyed town drunk, and Kamatari Fujiwara, who would go on to play the paranoid peasant Manzo in The Seven Samurai. The score was by Ichiro Saito, who had previously worked for Yasujiro Ozu and Mikio Naruse. Honda shared screenplay credit with Masashige Narusawa, who would later write Kenji Mizoguchi’s acclaimed Tales of the Taira Clan (Shin heike monogatari, 1955) and Street of Shame (Akasen chitai, 1956).

Despite its quality pedigree, The Man Who Came to Port was a step backward. Honda had neglected two of his strengths. His previous films showed isolated cultures in their natural surroundings, but remove the documentary stock footage and The Man Who Came to Port takes place almost entirely in nondescript interiors. The conflict between man and nature is never contemplated; the whale is little more than a harpooner’s target.

Critics assailed the picture. “There are so many spots that just don’t make any sense,” complained the Shukan Yomiuri newspaper. “The script … is very poorly done. The direction by Honda is so amateurish … They inserted actual whaling footage … which only adds boredom.” A Kinema Junpo reviewer actually praised the film’s visual style, but added, “What director Honda needs to learn is how to make the drama part better … It needs a little more of a climax.”

On location for Adolescence Part 2.Courtesy of Honda Film Inc.

———

Honda’s next feature revisited ideas explored in The Blue Pearl: conflict between traditional and modern values, anxiety about encroaching Western influence, and the impact of these pressures on a small, isolated group of people. The story again concerns a pair of star-crossed lovers subjected to the community’s harsh scrutiny, but this time the protagonists are high school students, whose problems are rooted in a generation gap that was widening fast in the years after the war. In Adolescence Part 2, Honda created a vivid snapshot of life in a small Japanese village amid the social, political, and economic changes of the Occupation. The film offers an interesting contrast to better-known works covering similar ground, for Honda had a more sympathetic view of Japan’s postwar youth than did some of his contemporaries.

Adolescence Part 2 was a follow-up to Toho’s successful coming-of-age drama Adolescence (Shishunki, 1952), directed by Seiji Maruyama. Set in a small town surrounded by mountains, Adolescence focuses on a group of students at a high school located adjacent to a red-light district full of unsavory establishments, and some of the youths are lured down the wrong path. The film ends with a teacher leading a drive to clean up the town.

The public response to Adolescence exceeded expectations, and Toho approved a second installment.16 During preproduction for Adolescence Part 2, high school students were asked about their problems and experiences, and their stories were incorporated into the screenplay by Toshiro Ide and Haruo Umeda. The cast includes veteran actors in the adult roles and members of Honda’s emerging stock company as the youths, including a young Akira Kubo (also in the original Adolescence, playing a different character), Ren Yamamoto, and Toyoaki Suzuki. Two roles were played by actual students after auditions were held across Japan.

Adolescence Part 2, though set in a similar locale and featuring some of the same actors, is not a direct sequel to Adolescence. Shot on location during the hot summer months in Kofu City, Yamanashi Prefecture, the story concerns a group of high school friends in a small town located in a mountain basin. The group meets regularly for after-school study sessions, stoking gossip among teachers, parents, and locals. Some don’t like boys and girls staying out together at night, others wonder if the kids have left-wing leanings, and still others object to one of the group’s meeting locations, a girl’s house that doubles as a snack bar owned by her parents and frequented by seedy types.17 Toho’s promotional materials for Adolescence Part 2 lay out the film’s theme: “Puberty is a time where the young contemplate life and try to face it straight on, with all seriousness. However, the adults view this pubescent period as something dirty.” The youths wrestle mightily with pangs of sexual awakening and longing for self-identity, none more so than Keita (Akira Kubo), whose defining character trait is baka shojiki (honesty to a fault). This is evident when the boy costs his sumo team a championship trophy by pointing out an illegal move by a teammate.

Keita and his classmate Reiko (Kyoko Aoyama) take a walk in the woods alone and become intimate. Afterward, both are racked with guilt; Reiko, walking in a stupor, is hit by a car. The local press calls it a suicide attempt, the result of teenage momoiro asobi (fooling around; literally, “peach-colored play”) gone too far; and because both teens’ parents are prominent community members, scandal erupts. The parents quell the uproar by pushing Keita and Reiko toward marriage, which further suffocates the youths. Keita goes into the mountains, seemingly intent on suicide, but is saved by a teacher. Cooler heads prevail and the two are given a fresh start. Reiko goes to stay with relatives, and Keita transfers to a school in Tokyo.

Directing actress Kyoko Aoyama in a pivotal scene of Adolescence Part 2.Courtesy of Honda Film Inc.

Having spent his early youth in a small mountain town not entirely unlike the fictional one here, and having been a kid with a zest for reading and the son of a priest, it’s possible that Ishiro Honda identified with the youths in Adolescence Part 2, and this might explain his exceptional compassion for the plight of his young characters. During the 1950s a good number of Japanese films depicted tensions between the Meiji generation that led Japan to war and the kids who came of age during the Occupation. The most noteworthy of these took a conservative and rather harsh view of youth. An extreme example is Keisuke Kinoshita’s A Japanese Tragedy (Nihon no higeki, 1953), which portrays teens and young adults as flagrantly disloyal and disrespectful toward their parents and elders, and is a classic of the enduring haha-mono (mother film) genre.

In Adolescence Part 2, the line in the generational sand is clear. An adult looks askance at some teens and notes disapprovingly that there is “a huge difference from when we were young. It was just war, war, war for us.” Elsewhere, some parents are reading a newspaper article titled, “Parents are too carefree: a dangerous age for rebellion.” Honda’s direction evenhandedly illustrates the rift, taking the adults to task for their hypocrisy while not letting the wayward youths off the hook. This isn’t a story of teenage delinquency, but of the widening gap between old and young and the upheaval of long-held traditions.

In early scenes, Honda contrasts the earnest teens with the hypocritical, quick-to-judge adults, some of whom gossip about the kids while practicing at an archery range; when they miss the target, it’s a nice visual metaphor for the adults’ cluelessness. The students are shown reading the French philosopher Alain and engaging in deep discussion; the teachers are shown reflexively siding with the cops after some of the kids are mistakenly arrested and accused of hanging out in a bar. And while the grown-ups worry about the boys and girls staying out late together, it’s the adults who think about sex, as evidenced by a bar patron reading a kasu tori magazine (lurid periodicals, popular after the war). Eventually Honda replaces black-and-white absolutes with shades of gray—such as when it is revealed that a female student’s sister is actually her mother, posing as the girl’s older sister to hide the shame of a teen pregnancy and a fatherless household; the woman’s revelation is a warning to the kids not to repeat their elders’ mistakes. As for the youths, it turns out that their parents’ concerns were not all unfounded. As Keita and Reiko hike into the mountains, the sexual tension builds between them; and when they stop to rest on a rock, Keita makes his move, and the couple kisses off-screen. The camera pans away to the rushing river below.

To the Western viewer, this would seem an unsubtle sexual metaphor—a train speeding into a tunnel—however, it’s not made clear whether the kids go as far as intercourse, and this ambiguity is key: Honda is less interested in whether the youths are going too far astray than in the impossibility of breaking free from the traditional values of family, community, and by extension the whole of Japanese society. In 1950s Japan, the mere appearance of such inappropriate behavior could result in unbearable shame and scorn. These two adolescents, seemingly free and independent minded, are instantly changed forever by a simple, universal act that’s part of growing up. They are burdened with the guilt of having failed to meet expectations and are duty-bound to suffer the consequences, even if it means a life of unhappiness.

This image has been redacted from the digital edition. Please refer to the print edition to see the image.

Poster for Adolescence Part 2, featuring Akira Kubo and Kyoko Aoyama. © Toho Co., Ltd.

Honda elicits fine performances from the young cast, particularly from Kubo, who plays Keita with the sort of muted angst that is at once completely Japanese but universal in the boy’s confused attempts to understand girls, parents, and the looming specter of manhood. There is a powerful sequence in which Keita, beaten and bruised in a fight, is bandaged by a girl who has a not-so-secret crush on him. As Keita lies still, the girl softly kisses him; but rather than accept her affection, the boy walks out and wanders to the school swimming pool and, in a scene breathtakingly shot by cinematographer Tadashi Iimura, swims laps in the moonlight as if to wash off the confusing, conflicting emotions. Keita suffers quietly, internally, worlds removed from contemporary Hollywood teens, who were shouting “You’re tearing me apart” at their own out-of-touch parents. Kubo, just sixteen when this film was made, was beginning a long and fruitful acting career. During the 1950s and 1960s, he mostly played supporting roles as impetuous, hotheaded romantics and heroic types in program pictures ranging from comedies to war dramas. He would appear in numerous other Honda efforts and also play significant parts in Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (Kumonosu-jo, 1957) and Sanjuro (Tsubaki Sanjuro, 1962).