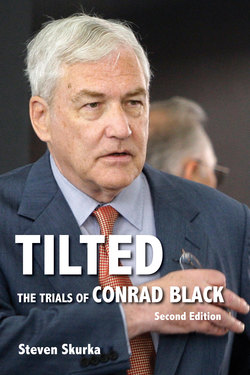

Читать книгу Tilted - Steven Skurka - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

March 14–19, 2007

ОглавлениеJury selection begins in Chicago for the trial of four former Hollinger executives — CEO Conrad Black, executive vice-president Peter Atkinson, former CFO Jack Boultbee, and general counsel Mark Kipnis.

David Radler reaches a $28.4 -million (all figures U.S.) settlement with Sun-Times Media Group (as Hollinger International is now known). Defence attorneys argue jurors may have been tainted by the news. Judge Amy St. Eve agrees to question jurors individually about their knowledge of the settlements.

Jury of My Fears

The Canadian jury is selected with the utmost courtesy and respect for the privacy of its members. Questions are rarely permitted during jury selection and the slightest hint of a personal question is immediately frowned upon by the presiding judge.[11] It is not a jury of twelve angry men but rather twelve unknown men (and women) that is ultimately chosen. I discussed the rather anonymous method by which Canadian juries are chosen with a noted criminal defence lawyer from Los Angeles, David Elden. He surprised me with his considered view that probing jury questioning invariably benefits the prosecution. Liberals proudly display their civil liberties credentials, whereas law-and-order conservatives are far more reticent to expose their pronounced views.

I recall a case in which I was defending a young man charged with criminal negligence causing bodily harm. In an attempt to take his own life, he had filled his home with gasoline and intended to set it aflame while he sat inside. As his painful moment of reckoning approached, he stumbled to the phone and called 911 to outline his lethal plan. As the dispatcher purposely delayed my client with protracted questions about his background, police rushed to the scene. Alas, at the very second that my client flicked his lighter, a police officer was at his front door. The ensuing explosion sadly caused the poor officer severe injuries, while my incredibly fortunate client left his kitchen chair without a bruise or scratch to his body.

As I perused the list of prospective jurors, I noticed that one man had listed his occupation as a director. I wondered if he was a director sitting on a board or perhaps more glamorously a movie director. Of course the distinction was meaningless to my selection, but my acute curiosity forced me to probe the matter further.

“May I ask you, sir, what type of director you are?”

“A funeral director,” was the surprising response.

I chose to exercise one of my permitted twelve peremptory challenges. I haven’t the foggiest idea why I did so other than perhaps that I unfairly chose not to associate myself for two weeks with someone in the morbid business of death. He might have been a delightful and gregarious fellow, but with the paucity of information in my possession, I could only resort to the worst form of stereotyping.

It was therefore striking for me to observe the elaborate jury selection process in the Conrad Black trial. All of the potential jurors had completed lengthy written questionnaires before they joined the panel in the courtroom. The trial judge, Amy St. Eve, was clearly a prodigious worker (the barista at the Starbucks by the federal courthouse related that the judge was there faithfully at six every morning) and meticulously read every word of the responses. In a warm and cheerful voice, she began to quiz the panel members individually as they were called forward. There were a few embarrassing moments. When asked if someone close to him had been arrested or charged with a crime, one man answered that his son was in jail for selling drugs.

A few common themes began to emerge. Canada fared poorly in some instances, with opinions of the country ranging from socialist to anti-union. An unsettling number of prospective jurors had experience with identity theft in their family. A number of them had signed non-competition agreements at work. Enron merited repeated mention; one man spoke of a good friend losing his retirement savings in the Enron debacle. It was clear that the dots were being connected from Enron to the allegations of corporate pilfering by Conrad Black. The comparison was unwarranted. As Peter Henning, a law professor and former U.S. securities lawyer, noted, “What will handicap the government … to a degree is [that it’s] not the Enron/WorldCom type situation where you had people losing their jobs and the company collapsed.”[12]

It was actually to Conrad Black’s advantage that very few potential jurors professed the slightest bit of knowledge about his identity. Unlike many Canadians, they could start the trial without sharply negative views about the man already firmly embedded. The front page of the business section of the Chicago Tribune carried a column, titled “Black’s trial no big deal for city,” that described Conrad Black as “more than a nobody and not quite a somebody.” I was interviewed by four local Chicago television stations, including FOX for FOX Chicago Sunday, and I was repeatedly pressed to explain to their viewers: who is this guy Conrad Black and why do people in Canada and England care so much about him?

One member of the jury panel commented that she couldn’t see anyone making tens of millions of dollars legally unless they happened to be Donald Trump. The judge reminded her that there are many people who make lots of money through legitimate means. Conrad Black’s fondest wish was that some of those very people would appear in his jury pool, but perhaps ominously for him it was otherwise. For the most part, the approximately 150 members of the Black jury panel were hard-working blue-collar workers who might find it challenging to relate to taking a trip to Bora Bora on the company tab.

I believed that Conrad Black’s jury could overcome any prejudices they might harbour about a man amassing obscene amounts of wealth. The larger challenge for the defence would be to withstand the barrage of scorn by the jury for their unsympathetic client. In the forty-five-page questionnaire that was completed by the jury pool, there was significantly no question directed to the ability to remain impartial with a haughty and arrogant defendant.

I happened to be listening in my hotel room this weekend to a recording of a Neil Young concert performed at Massey Hall in Toronto in 1971. I was struck by a memorable line from one of his songs: “I crossed the ocean for a heart of gold.” Conrad Black crossed the ocean for the title of lord. That is the rub in the man. The theme of this trial isn’t Braveheart but rather Coldheart. The enormous challenge for the cross-border dream team of Eddie Greenspan and Edward Genson will be to convince the jurors that although they might dislike their client and view him as an unworthy dinner companion, that doesn’t make him guilty of fraud and racketeering.

There is another challenge the defence faced that flowed from the overly indulgent American attitude to free speech. In Canada, the jurors depart from the courthouse as discreetly as they entered. It is a criminal offence for any juror to discuss their deliberations. During jury selection for the Conrad Black trial, Judge St. Eve quickly reminded any potential juror who expressed a concern about the media crush surrounding the case that they didn’t have to speak to reporters after the verdict. However, it was implicit that the option was there for them to speak as freely as they wish. They would also have the option to write about the case and seek large book contracts. Which result carries more promise of lucre — bringing down a financial titan and lord or vindicating him?

It is inconceivable that a system of justice should provide any enterprising juror with an incentive to achieve a particular outcome in a criminal case with the consequences to the defendant’s liberty so severe. Welcome to America, land of opportunity.

Gagged

There were seven lawyers congregated around Conrad Black at his counsel table. By my quick calculation, there were more attorneys in the courtroom than at a bar convention. Everyone seemed to be in a cheerful mood. Of course the jury hadn’t heard a drop of incriminating evidence yet. I watched Eddie Greenspan sharing a light moment with Barbara Amiel that left both of them smiling.

I noticed that there was little repartee between Greenspan and Genson and the lawyers at the other defendants’ tables. I asked Jane Kelly, one of three lawyers from Toronto on Black’s defence team, if there was any friction among the various defence camps. I was assured by “Ambassador Jane,” as she referred to herself, that a conciliatory accord had been reached and that, in the immortal words of John Lennon, everyone was prepared to give peace a chance. Jane’s diplomatic role was to attempt to ensure that no dangerous Scud missiles were launched by Black’s co-defendants in his direction. Black had been listed first on the indictment by the prosecution, which left him vulnerable to an ambush.

There was one last matter for Judge St. Eve to consider before the jury was called into court for the commencement of the trial. An emergency motion had been brought by the Chicago Tribune seeking the release of the identity of the twelve jurors and six alternates selected for the trial. It might make sense to protect the anonymity of the jurors if this was a terrorism or organized crime case where legitimate security concerns were raised. However, this was a trial where the exhibits would be paper rather than guns and autopsy photos. The defendants in the case were a group of largely paunchy middle-aged men who seemed about as threatening as the servers at the coffee shop on State Street pouring double and triple espressos.

The lawyer for the Chicago Tribune highlighted the broad issues at stake in his court filing:

There is no justification for an anonymous jury. The full names of all prospective jurors have already been read aloud in open court during [the selection process] making the retrospective sealing of the ultimate jury both an ineffective and inappropriate measure. But more importantly, sealing the list of juror names in this public criminal case is an extraordinary measure that is not warranted under the circumstances and violates the public’s First Amendment and common law right of access.

I had only been at the trial for a few days and already heady issues of the First Amendment and freedom of expression were being raised. I was probably the only person in court enjoying the constitutional tug of war. I was actually absorbed by the notion of six people sitting as alternates through a trial that could last for months and then simply being told to go home when the jury started its deliberations. In Canada a trial begins with twelve jurors and isn’t compromised unless more than two jurors have to be excused during the trial. That is a rare occurrence.

There are profound differences in the American and Canadian approaches to freedom of expression. In the U.S. a man can stand on a street corner preaching genocide.[13] The Canadian approach is more nuanced and sensitive.[14] Although a wide berth is given to unpopular and even untruthful ideas, it is recognized that in order to protect vulnerable communities, there is a point where a democracy can properly limit freedom of speech.

I was astounded to find that the media was free to publish or broadcast the content of the pre-trial hearings in the Black trial. There were no boundaries or restrictions. In America, a newspaper can print the detailed and damning confession of a defendant that later is excluded because the arrested party was denied his right to counsel. By contrast, in a Canadian courtroom, the bail hearing, the preliminary hearing, and all of the pre-trial motions are off limits to the media for reporting until the trial has concluded (or in some cases until the jury is sequestered). There can be criminal sanctions if an order banning publication is deliberately flouted.