Читать книгу Tilted - Steven Skurka - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеFor my part, I believe I have made it clear to fair-minded observers and will continue to do so that I committed no illegalities, I made the most I could of my time in prison, enjoyed teaching there, and my career as a writer has flourished. My financial condition is quite satisfactory. I have responded as well as I could to Radler’s treachery and other unbidden events …

— Conrad Black in an email to the author, May 23, 2011

Conrad Black’s final opportunity for vindication in his costly legal struggle[1] that deprived him of over two years of his freedom took place in the Dirksen Federal Building in Chicago in a ceremonial courtroom. The courtroom was reserved for special occasions and a hearing was set to proceed before a panel of three judges from the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. Black had already secured his place in American legal lore with the United States Supreme Court’s decision in his case. The decision of the Supreme Court to hear the appeal was regarded by Black’s own lawyers as an “unbelievable” achievement. The odds of obtaining a Supreme Court review were calculated to be about one in one hundred.[2] Black had managed to overcome such daunting odds to subsequently obtain a ruling from the nation’s highest court that placed his three remaining convictions for mail fraud and his obstruction of justice conviction into jeopardy. The showdown would unfold in Chicago with the Court of Appeals acting as the arbiter of Black’s legal fate.

Conrad Black was recognized as a celebrity figure in the Dirksen Federal Building. His status was confirmed on a mounted board adorning the wall immediately outside of the ceremonial courtroom. There in bold lettering was an outdated, and slightly inaccurate, account of Conrad Black’s case. The inscription on the board read as follows:

The world’s media came to Dearborn Street in 2005 when U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald brought eight criminal charges against international newspaper mogul Conrad Black, Baron Black of Crossharbor. Four new charges were added later that year, alleging racketeering, obstruction of justice, money laundering, and wire fraud. Under the racketeering count, the government sought forfeiture of more than $92 million. A media circus erupted on the streets surrounding the Dirksen Building with photographers jostling one another for shots and staking out all four corners of the city block. After 12 days of deliberation, the jury found Black guilty of three counts of mail and wire fraud and racketeering. On December 10, 2007, Black was sentenced to 78 months in jail. A subsequent appeal to the Seventh Circuit was denied; Lord Black has appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Conrad Black was likely the first British Lord ever tried in the courthouse. Black’s Chicago-based veteran attorney, Ed Genson, had announced to the local media that he had never defended a Lord before.[3] Perhaps the novelty of the lordly designation explained the inclusion of Baron Black recorded on yet another board in the hallway capturing the “famous faces” that had graced the courthouse as trial litigants in the past. Notably, Al Capone wasn’t among the group. Conrad Black featured prominently on a list of such notable historical figures as Thomas Edison, Charlie Chaplin, Marcus Garvey, John D. Rockefeller, Joseph Smith, and Alexander Graham Bell.

The atmosphere in the courtroom in the moments leading up to the hearing was cordial and had the feel of a reunion. It was homecoming week for three of the trial prosecutors in Conrad Black’s case as they hugged each other in warm embraces on the side of the courtroom. Two of them, Eric Sussman and Jeffrey Cramer, had left the U.S. Attorney’s Office shortly after the trial concluded, a feature of a lucrative revolving door for American prosecutors in high-profile cases. Sussman, the former lead prosecutor, had secured a partnership and was head of regulatory enforcement and white-collar litigation practice at the Chicago law firm of Kaye Scholer. Cramer became the managing director at the Kroll consulting firm, a corporate fraud and internal investigation company.[4]

Sussman recognized me from attending the trial of Conrad Black and was quite gracious as he greeted me in my seat in the front row of the gallery. He referred to the book that Conrad Black was reportedly writing and was curious to learn if it was still being published. Black’s book was also the topic of discussion on the appellants’ side of the rectangular courtroom. Richard Greenberg, Jack Boultbee’s counsel, asked a member of Black’s legal team if either he or Gus Newman, Boultbee’s trial lawyer, received mention in Black’s forthcoming book. The cheerful response was that “it’s a great story. It has great potential.”

Michael Schachter was acting as the attorney for another of the co-defendants, Peter Atkinson. Schachter was formerly a federal prosecutor in New York and had played a key role in the successful prosecution of Martha Stewart for making false statements and conspiracy. During the trial, Schachter was confronted by Rosie O’Donnell, who asked him if he wanted his children to grow up knowing him “as the man who took down Martha Stewart.”[5]

It required a measure of legal acumen on Schachter’s part to even permit Atkinson to be included in the appeal in Chicago. After the initial disappointing result in the Court of Appeals, Atkinson, with roots in Toronto, had abandoned any effort to appeal his case further. Peter Atkinson suffered more than any of his co-defendants at the loss of reputation after the trial and had become increasingly fragile. It was decided that Atkinson would focus on being transferred to a Canadian prison and seek early release on parole. The U.S. government wouldn’t consider his transfer to a Canadian prison until his appeals were resolved. When the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to review Black’s petition, the first telephone call that Eric Sussman received was from a frantic Michael Schachter. He shouted into the phone with the startling news of the development in the Supreme Court. Sussman attempted to calm his adversary with a few soothing words about Atkinson’s impending prison transfer to Canada. Schachter refused to be placated. He later discovered an obscure provision in the Supreme Court rules that allowed his client to join the appeal in the nation’s highest court.

Conrad Black’s final co-defendant was Mark Kipnis. Ron Safer was Kipnis’s lead counsel at both the trial and series of ensuing appeals. Safer, the managing partner of a national law firm, Schiff Hardin, was a former chief of the Criminal Division in the U.S. Attorney’s Office and supervised one hundred U.S. Attorneys in the division. He was very familiar to the prosecutors in the case. Sussman described him as an outstanding advocate and later conceded that it would have been beneficial not to have him in the courtroom as opposing counsel.

Ron Safer was carrying an additional burden as he strode into court for the appeal. He genuinely believed that Kipnis was an innocent man. He rued his miscalculation at trial of ignoring common sense and following the advice of a jury consultant by remaining firmly in the background of the case. A low-key approach plainly was a horrible plan when 90 percent of the witnesses at the trial dealt with his client who had prepared the paperwork as in-house counsel. Safer had “zero doubt” that Kipnis’s convictions were a miscarriage of justice. It marked a hollow victory that the government had sought a twelve-year sentence against Mark Kipnis, but Safer had secured probation for his client. The jury’s verdict was devastating, and Safer was left feeling depressed after the trial and experienced difficulty getting up to go to work.

Conrad Black’s venerable counsel at the hearing was Miguel Estrada, a former assistant to the U.S. solicitor general and part of an emerging breed of lawyers who specialized in Supreme Court advocacy.[6] His law firm of Gibson Dunn in Washington had attained a seminal victory in the case of Bush v. Gore that became a decisive factor in the outcome of a presidential election. Estrada had played a critical role in the hastily prepared winning argument before the U.S. Supreme Court. Conrad Black referred to Estrada as “brilliant” and to his legal writing as “completely rapacious.”

The judge who sat imposingly at the centre of the panel in the Court of Appeals was Richard Posner. Posner, a Reagan appointee and law professor, had been a federal Court of Appeals judge for more than a quarter of a century. In some quarters of the legal community, he was revered. Albert Alschuler, a criminal law professor at Northwestern University School of Law, described Posner’s standing as the most prominent legal scholar of the past sixty years. He was also the most prominent judge in America not sitting on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Judge Posner was the author of a number of wide-ranging books on law, economics, and literature, including one book devoted to the regulation of sexuality. It was motivated by his “belated discovery that judges know next to nothing about sex beyond their own personal experience, which is limited.”[7]

The hearing before the Court of Appeals represented the second appeal for Conrad Black before Judge Posner. The first round was marked by a series of caustic exchanges during oral argument between Posner and Black’s appeal counsel, Andrew Frey. The ultimate dressing down came with Judge Posner’s claim that a portion of the evidence had to do with “pretty naked fraud.” Judge Posner also exhibited a palpable disdain for Conrad Black. The reasons were unclear, but Posner had once disparaged Conrad Black in one of his judgments, noting that he wasn’t as well known or as colourful a figure as the former governor of the state of Illinois, Rod Blagojevich, who had been accused of participating in a political corruption crime spree.[8] Judge Posner’s characterization of Black’s colourful status was debatable. Blagojevich hadn’t even rated as one of the famous faces on the mounted hallway board. His place, however, was secure for another board in the courthouse highlighting the fact that six Illinois governors had been indicted during their administration or after. Even a Lord couldn’t qualify for that board.

The U.S. prosecutors have the ability to poison the wells with a media trial; they have huge procedural advantages in delays, notice periods, and their ability to discourage the appearance of defense witnesses by their ability to expand the range of questions where appearance is voluntary. The great majority of judges are former prosecutors, the prosecutors speak last to the jury, and the Fifth, Sixth, and Eighth Amendment rights of due process, the grand jury as a guarantee against capricious or malicious prosecution, of no seizure of property without just compensation, of prompt justice, an impartial jury, access to counsel (of choice), and reasonable bail, have all been put to the shredder, and I didn’t receive any of it.

— Conrad Black in an email to the author, May 23, 2011

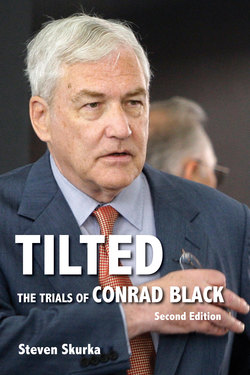

Conrad Black with his lawyers Miguel Estrada, Carolyn Gurland, and David Debold at his resentencing hearing.

Sketch by Cheryl Cook

American justice is very different than the justice meted out at the Old Bailey or in a Canadian courtroom. Justice isn’t blind in America. It perennially favours the side of the government. It is also a system of justice that is desperately in need of reform. The current U.S. Attorney General, Eric Holder, acknowledged that “too much time has passed, too many people have been treated in a disparate manner and too many of our citizens have come to have doubts about our criminal justice system.”[9]

The unfairness is evidenced by the rampant over-criminalization that infests the American justice system. There are over four thousand federal crimes with thousands more regulatory provisions that allow for criminal sanctions. A significant number of federal crimes lack any meaningful requirement for the culpable mental state of criminal intent.[10] According to Jim Levine, the president of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL), the largest group of criminal lawyers in America, the proliferation of criminal sanctions has led to profound and disturbing consequences:

The hallmarks of enforcing this monstrous criminal code include a backlogged judiciary, overflowing prisons, and the incarceration of innocent individuals who plead guilty not because they actually are, but because exercising this constitutional right is all too risky. This enforcement scheme is inefficient, ineffective and, of course, at tremendous taxpayer expense.[11]

The honest services fraud statute, one of the two alternative theories of mail fraud that were presented to the jury at Conrad Black’s trial, was a prime example of a legal code that had become “a vast, vague, and unpredictable invitation to selective enforcement.”[12] This over-reaching fraud statute that was zealously relied upon by government prosecutors for over two decades failed to limit the key phrase in the statute of “intangible right of honest services.” Gerald Lefcourt, a leading white-collar defence lawyer from New York, outlined the law’s potential for abuse:

With the power that prosecutors already had with unlimited resources and leverage, the addition of the impossible to define, intangible ‘honest services’ fraud statute made prosecutors all powerful and god-like with the ability to indict or threaten anyone who remotely did something unappealing or unethical. It was the kind of law that totalitarian governments would embrace, enabling them to put anyone in their cross hairs at any time.

The introduction of honest services by prosecutors in Conrad Black’s case was the catalyst to his successful appeal in the Supreme Court. The honest services law widely expanded the roadmap for the jury to convict. During the oral argument at Black’s appeal, one of the Supreme Court justices, Steven Breyer, stated that people sometimes joke that it would be simpler to have only one criminal law: “It is a crime to do wrong.” Sometimes adding, “in the opinion of the Attorney General.”

America is the empire of illusion where many of its inhabitants cling to the reassuring message that they live in the greatest nation on earth, a mythical narrative that is given the aura of uncontested truth.[13] An extension of this insular belief is that the United States, a country that continues to harbour the odious spectacle of the death penalty,[14] is endowed with a superior system of justice. It is a facile conclusion.

America is a nation where currently about one in every hundred of its inhabitants is behind the bars of a prison cell. The “rough justice” in America has resulted in overcrowded prisons, and never in the civilized world have so many been locked up for so little.[15] With less than 5 percent of the global population, the United States has almost one quarter of the world’s prisoners. Canada’s incarceration rate, by contrast, is less than one-sixth of the U.S. rate, despite sharing a relatively similar economic and political system.[16] The U.S. Supreme Court recently ruled that the state of California had to reduce the disturbing pattern of overcrowding in its prisons or, alternatively, tens of thousands of inmates could be released. As one commentator noted, “a majority of the justices decided that when a state approaches Stalinist standards of barbarity, something has to be done.”[17]

In his majority opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy cited the unsanitary and unsafe prison overcrowding: “To incarcerate, society takes from prisoners the means to provide for their own needs … A prison’s failure to provide sustenance for inmates may actually produce physical torture or a lingering death.”[18]

The Supreme Court of the United States cited Canada as a suitable model to emulate for prison reform. Statistics demonstrated that the prison population of Canada had been lowered without sacrificing public safety.[19]

Ed Genson spoke candidly of devoting his professional life to a system of justice in Midwestern America that was very heavily weighted in favour of the prosecution. It is essentially a terrible system, he acknowledged, that is pro-prosecution from the introduction of the indictment to the conclusion of the case. His experience in the Conrad Black trial exposed him to the Canadian justice system for the first time. Canada was an “eye-opener” for him. “You don’t have more crime in Canada,” he shared with me. “It can’t be that pro-prosecution rules in my country are beneficial.”

Patricia Holmes, one of Mark Kipnis’s lawyers, vividly described the injustice of the guilty verdicts against her client as something that “makes me hurt.” She pointed to the prosecutors in the case as overzealous. It is more important to do justice than to win, and she believed that they lost sight of this basic principle. Their decision to go after Kipnis’s assets in a forfeiture hearing exposed the prosecutors’ heavy-handedness.

Prosecutors are vested with remarkable power in America and it is exemplified by their control over the information provided to the defence. There is a significant risk that prosecutors are withholding relevant evidence. A featured USA TODAY investigation identified 201 cases since 1997 in which federal judges overturned convictions or faulted federal prosecutors, “the nation’s most elite and powerful law enforcement officials,” for misconduct. The failure to turn over evidence favourable to defendants represented the most common problem among those cases.[20]

The United States federal system gives prosecutors the power to hold back the statements of witnesses until their evidence-in-chief is completed. Ellen Yaroshefsky, the head of Cardozo Law School’s Jacob Burns Ethics Center, described the discovery process as playing a high-stakes poker game where the prosecutor, with remarkable power, possesses all the cards and the defence is left guessing. The failure to turn over evidence is a serious issue in documented wrongful conviction cases, although a comprehensive study of the problem can’t be conducted because 95 percent of defendants plead guilty. The Justice Department, Yaroshefsky noted, very strongly opposes open-file discovery, a process where prosecutors disclose all of the material gathered during an investigation.

One senior prosecutor offered the following justification for resisting open-file discovery: “I have found in the past when you have information that is given to certain counsel and certain defendants, they are able to fabricate a defense around what is provided.” The statement was made at a hearing before a federal judge in Virginia who threw out a murder conviction and death sentence as a result of prosecutorial misconduct that included withholding tapes of critical government witness interviews from the defence.[21]

The restrictive scope of discovery of the government’s case was only marginally modified in Conrad Black’s case. Ed Genson described situations in other cases where a judge would afford him five to ten minutes to read a witness’s statement before he had to embark on a cross-examination. At some point an unwritten rule developed that a minimum of thirty days notice would be provided. When Judge St. Eve extended the notice period to sixty days in the Black case, Eddie Greenspan, Black’s counsel from Toronto, noted with bewilderment that his American colleagues were thrilled. It was described as a “minor miracle.” He also confirmed that the statements, which were actual summaries prepared by an FBI agent, routinely arrived precisely as directed by the judge and never a day earlier.

Greenspan described the disclosure process in this fashion: “They throw every piece of paper at you. You receive millions of pieces of paper that aren’t collated or indexed. The disclosure can’t be presented in the Japanese language. That is what it seemed like. In Canada the Supreme Court of Canada set out a series of rational and highly principled rules surrounding disclosure in Stinchcombe.[22] They have absolutely no principles in the U.S.” According to Greenspan there were seven million pages of documents in the Black case, which were several million more than he managed to read personally. He added that during the trial, the prosecution kept turning over more discovery through their case-in-chief.

In Canada, witness statements that are actually statements of witnesses are routinely provided to the defence. Video or audio tapes of a material witness’s statement under oath and the original notes of the law enforcement officials involved with an investigation are basic components of the disclosure package that a Canadian prosecutor presents to the defence in a timely fashion. In America, such a practice would be construed as overly generous and a mistake. It would only provide a defendant in a criminal case with a level playing field. It is more laudable to corrupt the process than to promote its integrity. The overwhelming culture created in the American criminal justice system permits the prosecutors to punish defendants who exercise their right to go to trial and reward the legion of defendants who accept responsibility, plead guilty, and, most significantly, point fingers at others. Justice is effectively bartered in the prosecutor’s office, not fought for in the courtroom.[23] As one American defence attorney noted, “Practicing criminal law has become draining, dispiriting, and completely unsatisfying.”[24] In one case in Tampa, Florida, a lawyer bothered to have his fraudster client’s staggering sentence reduced to 835 years from 845 years with the tangible benefit of moving the sentence farther beyond the next millennium.[25]

The injustice begins with the manner in which indictments are instituted by grand juries under the federal system. Prosecutors decide what evidence will be submitted to a grand jury and are not obligated to inform the grand jurors about evidence of innocence. “The notion was that [grand juries] protects defendants-any defendants-against prosecutorial abuse is a fraud.”[26] The injustice is then compounded when the prosecutor packs the indictment with as many counts as possible. According to Ellen Podger, a law professor at Stetson University College of Law, “what may have once been a single white collar offence can become a multi-count indictment with charges of mail fraud, obstruction of justice, false statements and money laundering.”[27]

Several defence lawyers spoke to me about the built-in advantage that loading of counts in the indictment provides the government. Carmen Hernandez, a former president of the NACDL, emphasized that it is much more difficult to secure an acquittal with so many counts.[28] There is a psychological barrier for jurors to repeat a not-guilty verdict twenty times. This became a tangible hurdle for the defendants in the Black trial. Loading an indictment with a barrage of counts also serves the purpose of forcing guilty pleas.

The defendant who dares to accept the risk and conduct a trial is faced with the dismal prospect of a crushing sentence. Hernandez related to me the example of a defendant found guilty of distributing fifty grams of crack cocaine with a prior felony conviction for simple possession of marijuana. The sentence that would be imposed in such a case would be life imprisonment with no chance of parole. The defendant would die in prison.

Even an old trial warrior like Ed Genson felt trapped by the system’s plea inducement scheme. He shared with me a case that was scheduled for the following week. His client had been in a fight after being punched in the face. The client maintained that his assailant brandished a gun during the struggle. At that point he took out his own gun and shot his assailant once in the heart, instantly killed him. Genson had assessed his chances of winning the trial at about 80 percent. If his thirty-two-year-old client were convicted, he would serve a forty-five-year sentence of incarceration without a reduction of a single day. The prosecutor came with a generous offer that would leave his client serving about four and a half years in prison.

“What choice did my client really have?” he asked me. I had no suitable reply.

The sentencing guidelines that still retain a lot of force[29] were devised over twenty years ago, in theory to normalize the range of sentences imposed by judges and to infuse the process with some sense of due process. With hundreds of amendments added (almost invariably enhancements), the guidelines were used politically to increase sentences. The guidelines presently read like an elaborate tax code.

It is these sentencing guidelines that allowed the prosecutors in the Conrad Black trial to seek with straight faces a twenty-nine-month prison sentence for the star witness and co-operator David Radler, who pleaded guilty (premised on a fraud amount exceeding $30 million), and a dozen years for a minimal player like Mark Kipnis who dared to proceed to trial. The currency of co-operation in “the criminal justice flea market” has vitiated the very uniformity that the sentencing guidelines sought to achieve.

Why didn’t Mark Kipnis testify at his trial? Many, including Eddie Greenspan, believe that he should have. As Patricia Holmes explained to me, the decision began with an assessment of the risks involved under the guidelines that inhibit a defendant’s testimony. If Kipnis took the witness stand and was convicted, then it follows that he must have lied to the court during his testimony, and he would face a two-point enhancement of his sentence under the guidelines. Kipnis potentially would have faced three to five more years in prison. Even belated pangs of remorse offered to a probation officer after conviction could not expunge an enhanced sentence.[30]

Incredibly, the guidelines also permit prosecutors to rely on acquitted or uncharged conduct by a defendant, even for a charge as a serious murder.[31] As Greenspan observed, “If George Orwell were alive today he’d be hitting his forehead and wondering why he didn’t think of that one.” Genson described the unprincipled practice of artificially resuscitating a jury’s not-guilty verdicts as “disgraceful.” For instance, in a situation where a defendant charged with two separate sales of cocaine, one involving a single ounce and the other involving three kilos, a conviction on the lesser charge for the one-ounce sale permits the prosecutor to invite the judge to find on a preponderance of evidence that the defendant was involved in the three-kilo sale. The jury’s verdict becomes moot at that point and any sense of double jeopardy or due process is discarded.

If any Canadian prosecutor were to make a similar submission, he would be ordered to return to law school to relearn the basic rules of fairness and procedure. In America such a shameful practice of “acquitted conduct sentencing enhancement” is de rigueur, and the prosecutors in the Conrad Black trial eagerly attempted to hitch their cart to it.

More than 90 percent of criminal cases end in guilty pleas, magnifying the significance of the sentencing process.[32] Patricia Holmes, who is in the unique position of having been both an assistant United States attorney and a judge before becoming a defence lawyer, offered her opinion that the prosecutors just don’t lose. That is the justice system in America. It is a “tyrannical” system weighted heavily in favour of the prosecution, according to the former president of the NACDL, and it is left to the prosecutor or judge to exercise moderation.

It is tempting for prosecutors to unfairly exploit the leverage and power placed in their hands. Ron Safer made reference to its frightening influence in the Black trial in his closing address:

Pressure from the government is a truly awesome thing … You saw the response that several witnesses in this case had to that enormous pressure that the government can apply. [For] some witnesses it was dramatic … For David Radler, at a certain point he started confessing to everything the government asked him about, even though he had vehemently and vigorously denied these same exact points time and time and time again.

In Canada the trial of Conrad Black would have been a bench or judge alone trial. Eddie Greenspan suggested that the decision in those circumstances would have been a “slam dunk.” He believed that Judge St. Eve would have acquitted the defendants of all the charges they faced.

There are several reasons that the case was well suited to be tried by a judge sitting alone. Firstly, none of the defendants testified, and there is always a genuine concern that a jury will interpret that as a conspiracy of silence.

Secondly, the premise of the defence was that the vast millions of dollars of non-competition payments the defendants received were lawful and approved by the audit committee, but ultimately the defence conceded that no direct economic benefit to the shareholders resulted. That is not an attractive argument to make to a jury.

The final reason that a judge should have heard the trial was the incredible zeitgeist that lingered from the high-profile corporate fraud trials in America such as Enron, Tyco, and WorldCom. A new crime wave shook the public’s faith in corporate America and Wall Street, and business leaders became the new fodder for the prosecution mill as attitudes towards corporate governance hardened. The criminal charge of racketeering was being applied without discretion against corporate defendants.

A bench trial in America, however, requires the government’s consent. I was advised that in a high-profile case like the Black trial, consent would never be given because it would improve the defendant’s chances of winning.

Does anyone care that the American system is slanted in favour of the prosecution? Politicians boost the vast powers invested in American prosecutors. Judges are elected on get-tough-on-crime platforms exploiting a dire fear among Americans that the nation ever be considered soft on crime.[33] Prisoners are inhibited from using DNA evidence to support wrongful convictions while voters continue to reward prosecutors who are well known for locking up innocent people.[34] Congressional hearings are ordered for pressing issues like the use of steroids by professional athletes but never for the nation’s plague of miscarriages of justice.

Segments of the media openly favour the side of the prosecutor and vilify the presumption of innocence.[35] The most striking example is Nancy Grace[36] with her popular nightly show on HLN, an affiliate of CNN. She has been appropriately been described as a former prosecutor “turned broadcast judge-and-jury.”

“Working with a contingent of experts who have all the independence of a crew of trained seals, Ms. Grace races toward judgment, heedlessly ignoring nuance and evidence on her way to finding guilt.”[37]

Nancy Grace, however, isn’t the media’s sole offender. During the Michael Jackson trial, Tim Rutten, a respected columnist with the Los Angeles Times, commented on the secession by an entire segment of the news media from mainstream American journalism. He cited most of the commentator/personalities on FOX News (with the notable exception of Greta Van Susteren), the prime-time segment of CNN Headline News, and Court TV. He added the following: “These operations no longer feel constrained by even the minimal requirements of fairness, balance or dispassion required to practice American-style journalism. Instead, they operate as an apologetic cheering section for the prosecution.”[38]

It was Conrad Black’s naïve assumption that he could successfully navigate the turbulent stream of American justice and emerge unscathed with his liberty intact. He will have the experience of three years in a Florida federal prison to reflect on his grand miscalculation. David Radler, who pleaded guilty and in Black’s words “was exposed as a double-dealing cheat and liar and perjurer,” served about nine months of his twenty-nine month prison sentence before he was paroled in Canada.

Conrad Black’s case, however, did help to expose the systemic failings of a severely flawed U.S. justice system. Despite the obstacles, only fragments of the government’s original case against him and his three co-defendants remained. Ron Safer described the final result as a huge defeat for the government given where the case started. Black was left in the end with a single fraud conviction and an additional conviction for obstruction of justice for a crime committed wholly under Canadian jurisdiction. He overcame 99 percent of the total fraud alleged in the indictment. His share of payment in the proven fraud amounted to of $285,000. Black overcame a tilted prosecution that included the testimony of a watchtower audit committee that portrayed itself as the cast of MTV’s Jersey Shore.

Eddie Greenspan described “everyone talking in terms of forty years” if Conrad Black was convicted of every charge he faced. He certainly would have died in prison. Greenspan wryly observed that “we now know that there were no witches in Salem and there was no corporate kleptocracy.”

Barbara Amiel being attended to by court officials at Conrad Black’s resentencing hearing after reacting to the judge’s pronouncement of her husband’s sentence.

Sketch by Cheryl Cook

For Conrad Black, the final chapter in his case has not been written. As Jacob Frenkel concluded, Black will not be content with such an outcome. “He will go to every president in his lifetime until he gets a pardon.”