Читать книгу Tilted - Steven Skurka - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

March 20

ОглавлениеIn his opening statement, prosecutor Jeffrey Cramer tells jurors, “Bank robbers wear masks and use guns. Burglars wear dark clothing and use a crowbar. These four … dressed in ties and wore a suit.”

“He was not stealing from the company,” defence lawyer Ed Genson counters. “The company was stolen from him.”

The Cuddly Curmudgeon

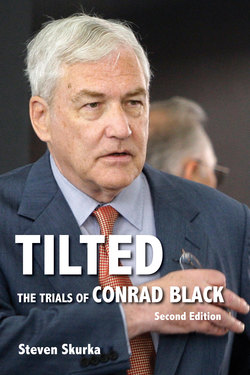

I applaud the subdued dress look (grey on grey) that Conrad Black has selected for his courtroom wardrobe. His extravagant lifestyle is featured in the prosecution’s case, so he doesn’t need to become a witness for his adversary by dressing flamboyantly. It would be most unhelpful, for example, for him to arrive at court carrying one of Martha Stewart’s Hermès handbags. I am reminded of the lawyer in my office who was defending a Penthouse model on a relatively minor drug charge. He took special efforts to warn her about dressing for the solemn occasion of a court proceeding. He was mortified to find her at the courthouse attired in a tight-fitting blouse, short skirt, and black fishnet stockings.

I feel as if I have jumped into a swimming pool only to find that the lifeguard has neglected to inform me that it isn’t heated. I watched in baffled dismay as the prosecutor, Jeffrey Cramer, delivered his opening address today with the same fiery rhetoric and flourish that I expect Abraham Lincoln employed for his stirring Gettysburg Address. Cramer’s opening was about as distant from the dispassionate and flat opening that a Canadian prosecutor would routinely give as Ontario, Canada, is from Ontario, California. In short order, a Canadian jury would be provided by the prosecutor with the anticipated menu for the trial without the enticing details for the recipe of each course. Regardless of whether the meal consisted of oysters or foie gras, the prosecutor’s voice would never rise with crackling excitement. Unappetizing introductions such as “I anticipate the evidence will be” or “I expect the witness will testify that” would be sprinkled throughout the curt summary of the case for the Crown.

I chatted with a journalist covering the trial for the Sydney Morning Herald and found that we shared a common view that Cramer’s opening address was certainly different than anything we had experienced in our respective countries. As he wagged his finger at Conrad Black and his co-defendants, Cramer railed about their looting of the Hollinger International shareholders of $60 million. With faint praise, he referred to the four defendants in the courtroom as some of the most sophisticated men the jury would ever see. Always be wary of the prosecutor who brandishes compliments. Cramer’s point to the jury was plain. The ruse of siphoning extravagant sums of money from the shareholders through various non-competition agreements would have been obvious to these astute businessmen. “It’s simple, it’s simple,” Cramer emphasized as he laid out the nefarious scheme of the four men. Cramer was a disciple of the “KISS principle” that all good trial lawyers understand: “Keep It Simple, Stupid.”

The prosecution appreciated that there was a gaping hole in its case. Every one of the contentious deals involving the non-compete payments to the defendants was profitable to the shareholders. This was not the financial undertow that resulted from the Enron debacle, where billions of dollars were plundered from the company as thousands of jobs and pensions of Enron employees vanished into thin air.

Jeffrey Cramer’s solution was to pull on the jurors’ heartstrings using a different approach. With a raised voice, he drew from the bank of wishful thinking. The two groups of victimized shareholders that he identified were elderly people who had bought Hollinger stock for their retirement and parents who had stocked their children’s college funds with Hollinger shares.

Cramer’s bag of trial tricks in his opening did not rely exclusively on emotional appeal. Plan B depended on frightening them.

“We all know what street crime looks like. A man knocks you down and takes your money. This is what a crime looks like in corporate law … Bank robbers use masks and carry guns. Burglars wear dark clothing and use a crowbar. These four [defendants] wore a suit and a tie.”

Now that it was settled for the jury that Conrad Black had robbed the Hollinger bank in sartorial splendour, it was Edward Genson’s opportunity to respond. He began by challenging the idea presented by the prosecution that none of the buyers of Hollinger International assets wanted a non-competition agreement with Black.

“I want you to remember CanWest,” Genson told the jury. In the colossal $3.2-billion deal between Hollinger International and CanWest, he explained, it was the purchaser who had asked for a non-competition agreement.

Eddie Greenspan listened apprehensively as his co-counsel continued his opening comments. As a thorough lawyer accustomed to meticulous preparation, Greenspan had repeatedly asked to see Genson’s script for the opening. Each of his requests had been rebuffed. Incredibly, he had no more idea of what precise words would be coming out of Genson’s mouth than did his adversaries seated at the prosecution table facing the jurors.

Greenspan’s worst fears were realized as Genson moved quickly on the offensive by stating that there was no theft from the company by Conrad Black. On the contrary, it was the company, Hollinger International, that had been stolen from him. It was a stinging rebuke to Cramer’s opening, but Greenspan worried that Genson had placed an unnecessary and impossible burden on the defence. In the spirit of Conrad Black as victim, the defence was on course to portray the individuals charged with the responsibility for corporate governance at Hollinger International as the true thieves in the night.

Genson touched on a theme in his opening that needed to be addressed directly. “You can’t allow the sparkle of wealth to alter the facts of the case,” he warned the jurors. A glare of wealth or even a blaring inferno might have been more apt descriptions of Conrad Black’s true economic health during the currency of the charges, but Genson’s point was sound. It was ironic that a defendant’s status among the super-rich had marked him as a displaced person before the jury. Whereas indigence might deprive a defendant of the resources to tussle in a courtroom on an even playing field, the trappings of wealth could translate to a badge of impoverished character.

The best of the four opening statements by the defence was reserved for the last. Ron Safer provided the jury with a stirring imitation of a closing address as he sandblasted the central government theory. The audit committee of Hollinger International, chaired by the former governor of Illinois, James Thompson, not only was aware of the non-competition agreements, but also, Safer noted, “approved them again and again and again.”

Safer’s opening sealed a unified front presented by all of the co-defendants. There were no early signs of finger-pointing or cracks in the defence. David Radler emerged as a dominant target. “Would you buy a used car from him?” Ron Safer asked. The implication was clear to the jury: a disreputable man like Radler, who tampers with the odometer and hides the rusty spots, can’t be trusted as a witness.

The headlines in the newspapers predictably captured the prosecution’s sound bite. As a typical example, the Financial Times carried the following banner to its Black trial coverage: “Hollinger chiefs ‘bank robbers in suits’, court told.” The buzz around the courtroom, however, was that after the defence openings concluded, the trial was a true contest. “I would acquit Mark Kipnis now,” one reporter stated only half-jokingly. The jury was engaged and listening. The jurors were ready to focus their spotlights on the evidence.

I was approached by Genson in the hallway at the break. “Are you the guy who called me a curmudgeon on channel 7?” he asked. I admitted that indeed I had used the description in an interview with the local ABC station. “All my friends are calling me about it. I have never been called a curmudgeon before,” he chided me, clearly crestfallen. I could only hope that my unintended slur would be forgotten after the auspicious start to the trial by the defence.

The first witness called to the stand by the prosecution was Gordon Paris. As Mr. Corporate Governance, he had replaced Conrad Black at Hollinger International and played a key role in the Breeden Report that was the precursor to Black’s criminal charges. It was Black who had invited Paris, an investment banker with a prestigious business degree from Wharton, to join the Hollinger International audit committee after questions were raised about some dubious management fees.

Eddie Greenspan assumed the task of cross-examining Gord Paris. It was Paris who had negotiated the $60-million settlement with Radler on the eve of the trial. Greenspan and the rest of the defence had expected the prosecution to open with a few minor witnesses, which would have allowed Greenspan time to get a sense of the unique U.S. style of questioning, but now the first witness in the case was awaiting his cross-examination. A famed Canadian barrister and QC was ready for his first foray in a Chicago courtroom. I suspected that the prosecution might regret calling Paris as their first witness. The only question that would linger after his cross-examination would be this: Is Paris burning?

Lord Blowhard of Crossharbour

The reasons behind the government’s decision to call Gordon Paris as the first witness in the trial were initially a complete mystery to me. Chronologically, his evidence related to the final chapter of the case after the alleged fraudulent scheme had been perpetrated. Perhaps the prosecutors assumed that Judge St. Eve would allow them to introduce the damning Breeden Report that cast Conrad Black in such a villainous light. The judge, however, disappointed them by ruling against that action.

Patrick Fitzgerald, the United States attorney closely observing the ebb and flow of the case in the background, was a master of strategy in the courtroom. I began to suspect that he understood that Conrad Black’s defence team was so anxious to discredit the case against their client that it would be virtually impossible for them to resist the urge to take the safer course and refrain from asking the first witness a single question. Paris would serve as the perfect foil for this artful strategy.

Stripped of his ability to refer to the incendiary Breeden Report (although he did manage to sneak in a mention in front of the jury), Paris was like a snarling dog straining against its leash to get at its prey. It should have been readily apparent to the defence that Black’s successor at the helm of Hollinger International offered little valuable evidence to the prosecutor in his examination.

As Eddie Greenspan quickly learned in cross-examination, Gordon Paris was a dangerous witness. The most memorable features of his evidence came during the re-examination by lead prosecutor Eric Sussman, after the door was inadvertently left wide open by Greenspan. Authorized employee benefits, Paris noted, didn’t extend to corporate perks such as birthday parties, New York apartments, or free access to the company aircraft. All three perks were the subject of separate charges in the indictment against Conrad Black.

The acclaimed Canadian lawyer struggled and looked badly out of place in the city where Clarence Darrow tried most of his cases. As the trial judge sustained the steady stream of objections from the prosecutors, Greenspan had the look of a wobbly boxer wincing from a succession of jabs to his abdomen. Greenspan’s confusion escalated to the point that on occasion he wasn’t certain if he had won or lost an objection. There was a series of long and awkward pauses at the counsel table as Greenspan was educated about some elementary rules of American criminal procedure.

For example, Greenspan attempted to ask Paris about a regulatory SEC filing that he had submitted ten months late. His American co-counsel had written out a sample of acceptable questions he could ask to demonstrate that Paris had lied to the SEC and that the filing was improper. Greenspan instead chose to ask Paris, “You did your best and made an honest mistake?” It was a theme that Greenspan hoped would resonate with the jury in considering Black’s conduct. However, the prosecution’s ensuing objection was quickly sustained and Greenspan was forced to justify his approach to Judge St. Eve in a voir dire outside the jury’s presence. Greenspan thought it was “nuts” that before he could present evidence to show the jury that Paris had made an honest mistake he first had to portray the witness as dishonest to the judge.[1]

At the lunch break, I overheard one of Greenspan’s co-counsel remark that he seemed unaccustomed to the American courtroom style. The start of the trial wasn’t the time and place, however, for a rudimentary lesson. I wasn’t prepared to count Eddie out, though. I doubted that Black’s legendary Canadian counsel would permit himself to be publicly shamed a second time with another dismal courtroom performance. And without some noticeable improvement by Greenspan, Conrad Black could begin to furnish his prison cell.

A positive sign for Black was that the jury listened intently to the evidence presented and took notes. Greenspan managed a few smiles in the jury box with his brand of self-deprecating humour, but he clearly had not yet developed any rapport with the jurors. It was still early in the ball game and these were only warm-up pitches. The lineup of star witnesses, including David Radler and members of the audit committee, would mark Greenspan’s true test with the jury.

In order to acquire one of the precious few seats in the courtroom reserved for the international media, I was required to line up at seven o’clock in the morning. The journalists covering the trial were generally very approachable and even helpful. There were a few grating comments that I chose not to respond to. One reporter blamed Eddie Greenspan for not pursuing a settlement for his client (generously assuming that Conrad Black would heed anyone’s advice).

In one discussion that I overheard in line, a journalist wondered why Black hadn’t repaid the questionable compensation he had received for the non-compete agreements. The notion advanced was that Black could possibly have avoided his current legal predicament with that simple gesture. Another journalist nearby scoffed at the suggestion that Black would ever pursue such a sensible course of action. “That would be like asking why Hitler didn’t bring back the six million Jews,” he said. I was beginning to get the impression that Conrad Black was reviled by a lot of people. His detractors didn’t attempt to disguise their hostility, either. But the only opinions that mattered to Black were those of the jurors, and he was indeed fortunate to be perceived by them as a stranger in their midst.

I have resisted the temptation thus far to lapse into the “Montreal bagel syndrome.” For the rare reader unacquainted with the malady, allow me to explain. It represents the rigid position that whatever one experiences outside one’s own city or town is always inferior to the home product. For example, anyone who has lived in Montreal, Quebec, will invariably inform you in a dismissive tone that the bagels in that cosmopolitan city are much better than the comparable fluffy and inedible bagels in Toronto, Vancouver, or Calgary. I suppose that would include David Radler, whose roots can be traced back to Montreal. With my legal analyst’s cap firmly in place, I have been a careful observer of the proceedings in the Black trial and on balance have been favourably impressed. By all accounts, Conrad Black is receiving a fair trial.

There are only four men among the group of jurors and alternates, and so it is remotely possible that Conrad Black’s legal destiny will be determined by twelve women. At least two-thirds of the jury will be female. The prosecution should certainly reflect on the wisdom of seeking to introduce several thousand files containing predominantly email exchanges between Lord Black and his wife, Barbara Amiel. Whatever the content of the myriad emails, their presence will create an image of spousal devotion, love, and romance for the jury.

I found the entire issue surrounding the admissibility of the Amiel emails perplexing. In Canada there would never be any question that they would remain sacrosanct and protected by marital privilege. While munching on a Montreal bagel, I raised the matter with a professor at the DePaul University College of Law in Chicago. Apparently, any communication between spouses that is outside the course of the marriage is not the subject of privilege. I never appreciated that marriage could so readily be divided into categories of business and pleasure. For example, what would an American court rule with regards to the following hypothetical example of an email exchange?

Dearest Conrad,

I love you dearly. May I please buy some Cartier earrings with the money you received from your latest non-compete payment? I want to wear them on the plane ride to Bora Bora ~ lol.

Babs

The emails of Conrad Black took centre stage at the end of the first week of trial. “Black’s Private E-mails Go Public at Fraud Trial,” read the headline in the weekend edition of the Globe and Mail. Conrad Black was documented in an April 2003 email delivered to audit committee members Marie-Josée Kravis and Richard Burt reassuring them in his unique bombastic style that he would crush any dissident shareholders: “I will take on the task of hosing down shareholders in need of it as some priority.” In another email, responding to questions about non-competition agreements, Black disparaged his challengers as victims of an “epidemic of shareholder idiocy.”

Are the jurors being swayed by these graphic emails capturing Conrad Black’s descriptive flair? Many of them laughed heartily as Eric Sussman struggled to pronounce the word “calumnies” in one of them. Genson pounced on the opportunity to offer his client’s assistance. That suggestion was greeted with more amusement by the jury.

Unfortunately for the prosecution, the emails were neither calumny nor calamity for Conrad Black. I expect that that the jurors will give very little weight to these pompous emails in their deliberations. The caution flag was raised clearly in Genson’s opening statement: “That proves nothing except that he has an arrogant attitude when he writes memos in the middle of the night.”

Genson’s opening was a precursor to a theme that the defence seized upon in the first week of the trial. Using a simple diagram to illustrate his point, Genson had outlined the geographical boundaries that separated Conrad Black and David Radler as they ran the third-largest newspaper empire in the world. It only followed that as the American community newspapers were sold to a variety of purchasers in Radler’s backyard, it was therefore Radler who oversaw the negotiations.

The first witness to testify about the purchase of Hollinger International assets was Peter Laino. Laino worked for a media holding company Primedia, that was involved in a $75-million sale that included American Trucker magazine. The agreement, which was negotiated exclusively with David Radler, included non-competes with Hollinger International and Hollinger Inc. for $2 million. Laino conceded in cross-examination that in all likelihood the deal was contingent on Hollinger International and its affiliates not being permitted to compete after the sale. There was no apparent ruse, despite what the prosecution had promised in its opening. This was a case in which the buyer really did request a non-competition agreement. The defence was off to a good start.

Canadian Curtsy

I have always liked prosecutors. I like them best when they lose my cases. They will, however, at least in a Canadian courtroom, always remain my friends. That is the courtesy title that we attach to our robed adversary. Imagine a particularly contentious moment in a heated trial when the prosecutor has pulled an outlandish stunt in front of the jury. In America, a sidebar is called to avoid any unseemly accusations being hurled in the well of the court. In hushed tones at the far side of the courtroom, the lawyers thrash each other with verbal barbs as the judge attempts to mediate the problem.

Contrast that to a trial north of the border, where the defence counsel politely rises and addresses the judge about the offending conduct: “With respect, your Honour, perhaps my friend should consider his words more carefully,” she begins. “His most inappropriate statement in front of this jury bears little resemblance to the evidence this jury has heard.”

The prosecutor then has an opportunity to reply in kind to his friend and the judge instantly rules on the matter. The trial then moves forward with almost seamless efficiency.

In the Conrad Black trial, I observed the team of four young prosecutors during the pre-trial motions, and they appeared to be a happy lot. A scowl on a prosecutor’s face is a sign of either a prickly disposition or displeasure with the flow of the evidence. A relaxed smile, however, is a troubling sign for the defence. During one of those interminably protracted sidebars that began to infect the trial, the trial judge’s remarks drew hearty laughter from the lead prosecutor, Eric Sussman, and his cohort Jeffrey Cramer. It was noticeable that none of the defence lawyers even feigned a laugh. One of them abandoned the sidebar and left the courtroom with his coat and briefcase.

The prosecutors were already gaining the upper hand in the trial. Every advocate must possess the artful skill of feigned laughter for when judges tell jokes during a trial. DVDs of Seinfeld episodes are freely handed out at judges’ school but to little avail. The finest judges recognize their inherent limitations and mete justice absent of any jocularity.