Читать книгу The Dingo Took Over My Life - Stuart Tipple - Страница 1

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеSometimes the slightest things change the directions of our lives, the merest breath of a circumstance, a random moment that connects like a meteorite striking the earth.

- Bryce Courtenay

The Azaria Chamberlain case will go down in Australian history as a disaster, in the league of train smashes, corporate collapses and medical failures. When each of these disasters is scrutinised in the aftermath, it is almost inevitably found that there were contributing factors which could have been recognised well in advance: lack of maintenance, miscalculations, cost-cutting, complacency, negligence, arrogance, recklessness. Such failures individually are often tolerated, to wit with a warning, caution or disciplinary action of some sort, but without upheaval, because other safeguards have been in place. But when a series of individual failures come together and there are no more safeguards, the pieces, as it were, lock into place. How many worksite foremen, viewing the aftermath of a fatal industrial accident, have asked: “Why wasn’t this checked?” How many chief executives, pondering a corporate collapse, have asked: “Why didn’t I heed that warning?” How many ministers of state, seeing a policy go belly-up, have asked: “Why he did not see that coming?” How many barristers, seeing a client go to gaol, have asked: “Why didn’t I pin that Crown witness down properly?” At any point in most sequences of events, safeguards have operated. Things have not worked out in places, but the overall operation has nevertheless proceeded, because other checks and balances have worked. Every time a financial analyst sees a risk in a proposed investment, and that is acted on, then a safeguard has worked. Every time a forensic scientist sees an inconsistency in a test result that casts doubt over the Crown scenario and says there is no confirmation, an effective safeguard has not allowed things to continue.

There are usually multiple safeguards, and sometimes the failure of some of them leads to a rescue operation. Sometimes, just the final safeguard holds up. More than a quarter-century ago a NSW Police superintendent, Harry Blackburn, came under suspicion as the perpetrator of a series of assaults and rapes in suburban Sydney. There were a number of safeguards against a wrongful conviction: the accuracy of eyewitness accounts, the competence of investigating police and of reviewing police, the scrutiny of the Director of Public Prosecutions. All these safeguards failed and Harry was charged and paraded in front of the cameras for all the world to see. As a result of the stress both his wife and daughter-in-law suffered miscarriages and Harry’s life was turned upside-down. But the headlong rush to total disaster was stopped in its tracks. A safeguard worked, being the competence of an officer who took over from the original investigators. He was the then Detective Inspector Clive Small. The brief was “full of holes”, Small said, in the face of a stiff opposition from superiors, and the prosecution was dropped.

In the Azaria Chamberlain case, a series of safeguards were in place and any blame, whatever it might have been, properly attributed. The couple lost their baby, seized in the jaws of a wild animal at Ayers Rock on 17th August 1980. An investigation followed. To the point of the initial coroner’s finding, in February 1981, that a dingo had taken the baby, the safeguards held firm. Then it was reinvestigated. There were further safeguards: the competence of the investigating police and scientific experts, the chance to air all the facts, if it came to that, before another coroner, and again if it came to that, the common sense of trial judge and jury, then perhaps of the Federal and High Courts of Appeal. As it turned out, one of these safeguards might have held, being the view of the case taken by the trial judge, James Muirhead, who saw through the nonsense and virtually begged the jury to acquit. But because of the authority of the jury decision, his urgings were overridden. Another safeguard almost held. Two of the five High Court judges hearing the Chamberlains’ appeal, Justice Lionel Murphy and Sir William Dean, found that the appeal should be allowed and the convictions quashed. But they were in the minority on the bench and that safeguard failed. As it turned out, all the safeguards failed. The Chamberlains were convicted, Lindy sentenced to life imprisonment with hard labour, Michael to a suspended sentence, and their lives were torn apart.

As the event was scrutinised, over and over again during the following three decades, it gradually dawned on officialdom – however long that took – that that had happened. The safeguards, or any one of them, should have held up. But with their total failure, the pieces fitted into place, and there was nothing to stop what followed. Then the question was asked, in a royal commission, why this had happened. Contributing factors became readily identifiable: the remote location, making immediate and expert crime scene examination difficult, the incompetence and arrogance of at least some of the forensic scientists, the ruthlessness and irresponsibility of media, making it near-impossible to have put together an untainted jury, the bigotry of the general public and the rigidity of the legal system.

So often, in these disasters, there are warnings. One such warning, had it been properly researched, was an inadequate performance of the principal scientific witness, Professor James Cameron, in a criminal case in Britain. As far as forensic science in general was concerned, there were warnings from previous cases, especially where prosecutions had been based on scientific rather than primary evidence, where evidence had been wrongly admitted or insufficiently tested, where expertise was assumed in an expert judgement when it should not have been. After Michael and Lindy Chamberlain were convicted over their baby’s death, the final appeal had to be to the Court of Public Opinion, which is at best fickle. In the Chamberlain case, it worked. But by the time that had been done – the coroner’s finding in 2012 reverting to what Denis Barritt had found in 1981 – the lives of everyone in the Chamberlain family had been ruined or severely affected.

Congratulations Australia! A baby is snatched away by a wild animal and the parents are universally vilified, convicted and punished. All those years and years, collectively, of education and training, all that experience of the police offices and scientists and lawyers, all those hundreds of years in which the legal system had been studied, scrutinised and refined, all that money spent on investigation and court proceedings, and yet this happened.

Michael and Lindy Chamberlain had no reason to believe nine-week old baby Azaria was in any danger when Lindy placed her asleep in their tent with their sleeping four year- old son Reagan. From that misplaced confidence, everything went wrong for the Chamberlains.

Having suffered the unimaginable trauma of losing their baby in these horrifying circumstances, they were thrust headlong into a world that was utterly unfamiliar to them, sneered at and pilloried throughout the nation, prosecuted and in Lindy’s case, gaoled for life. John Winneke QC, who represented the Chamberlains at one point, was to say it was like Beelzebub going ahead of them all the time, throwing things down which would come back onto them. Leaving aside satanic influences, it was simply a case of the safeguards progressively failing when they should have worked.

Into this mess was thrust Stuart Tipple, a 29-year-old provincial solicitor in New South Wales, retained because he was well-regarded professionally and a Seventh-day Adventist, like his clients-to-be, and in good standing with the Seventh-day Adventist (SDA) hierarchy. With limits to his own experience, he took the brief after the re-investigation was launched and plunged into unknown territory, an unchartered wilderness in which he was to experience frustration, persecution and denunciation. He was often a lone figure, attacked and denigrated over the following years within his own church community, pitching his resources against those of the government of the Northern Territory, which called on experts from the other side of the world. However like other solitary figures, caught in a blitz with nothing going right for them, he stayed calm and planned his moves, set his priorities and battled on. The one thing that went well for him was that both Michael and Lindy Chamberlain recognised his intrinsic value and stayed with him.

I encountered Stuart as a reporter on the Sydney Morning Herald. The media did not have a good image in the eyes of the Chamberlains, who had initially been frank and open but soon learned to be very wary. I was tarred with that brush as well. But had had some sort of rapport with them, probably because I was a churchgoer. With Stuart, it was a prickly relationship. Probably the worst moment was when Stuart had private negotiations with Brian Martin QC, then the Solicitor-General for the Northern Territory, about a possible release for Lindy. Stuart told the SDA hierarchy, who distributed the information in a confidential document. That was leaked to me and, in accordance with what I understood to be my obligations as a journalist, I publicised it, and that threw a huge spanner into works as far as negotiations with the Northern Territory went. Stuart once snapped at me in a lift saying I was just another of the reptiles of the press, to which I was about to say: “You’re talking about the way I do my job. What about the way you do yours, which is, essentially, winning a case from time to time and keeping some people out of gaol!” I told him a long time later that that would have been my response and even then, he recoiled.

For some years Stuart was harassed by critics urging him to step aside and let another team have a go. The urgings even went to his clients. But the Chamberlains stuck with him, as did the barristers he had retained, but he would scarcely have been human had he not been plagued by the darkest thoughts as to whether his critics were right. His strategy at times took him right out of the legal realm and into that of politics, public campaigns and media coverage. His principal focus was on the scientific evidence, upon which his clients had been convicted and over which he had always held the gravest doubts. He did all this while running a legal practice and a family, and dealing with some of the complications of family life. A royal commission exonerated Michael and Lindy and, after years of dithering, the Northern Territory though its coroner reinstated the original verdict that a dingo had taken the baby. Stuart Tipple had been vindicated even though, in their personal lives, Michael and Lindy Chamberlain had paid a terrible price.

Stuart invited me to join him in writing a book after seeing a play, Letters to Lindy, by Alana Valentine, at Sydney University’s Seymour Centre in September 2016. He had diary notes and a pile of correspondence that had been sent to him and his clients during more than 30 years handling the case. The letters were from all points of view, some from scientists, others from church members, many from the public, including some that were malicious. That included a couple of postcards to Lindy purporting to be from Azaria in the afterlife and asking her why she had not given Azaria a chance at life too. When I undertook this task, I saw it as Stuart’s story but he persuaded me to include some of my own story. This book is the product of what word skills I possess after more than four decades in journalism, coupled with Stuart’s learned contributions. This book is the joint effort of both of us. I have referred to myself in the third person, which is a little awkward. The book is meant to be about Stuart’s journey, but our journey was so intertwined that I decided it should be both our journeys, but with the emphasis on Stuart. The problem with writing a profile of Stuart, I must say, is that he is absolutely straight down the line, unemotional and tough. He could never be called eccentric or idiosyncratic. He did feel things deeply, but when the chips were down, and the going became very, very tough, Stuart was there, unflappable and unyielding. If anyone could be relied on to see a matter through, it was always going to be him.

In January 2017 when news came through that Michael Chamberlain had died, from some blood disorder, Stuart and I came together again. We attended the memorial service, as did others who had been with the Chamberlains for years, including Andrew Kirkham, who had been one of their counsels, and John Bryson, who had written the ground-breaking book, Evil Angels. So were Lindy and the Chamberlain children, her husband, Rick, and Michael’s wife, Ingrid, and their daughter Zahra, all in their own way, locking away their own deepest, saddest memories. Michael Chamberlain had said towards the end that he would not want to wish on anyone “the life that I have had”. Everyone knew what he meant. This book is an attempt to portray the experience of Stuart Tipple and others as they shared the pain year after year as they grappled with this legal catastrophe.

Malcolm Brown 30th June 2017

Members of my legal fraternity like to tell me “Well the system got it right in the end”. They don’t like to admit how badly it failed the Chamberlains. The Chamberlains’ exoneration was obtained despite the system and would never have been achieved without a combination of extra ordinary circumstances and “people power”. I was persuaded by a publisher to write a legal text about the Chamberlain trial as a notable trial. After completing a draft, I attended Alana Valentine’s play Letters to Lindy. This play inspired me to put the legal text on hold and join with Malcolm Brown to tell this story which allows me to disclose letters I received from Lindy, her parents and key players wrestling with this tragic miscarriage.

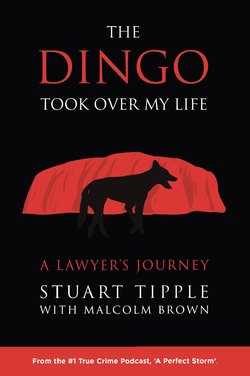

Given the important part the media has played throughout I decided this book should be a joint effort with a reporter who has been part of this saga from its beginning. There was no one better suited than Malcolm Brown. Our relationship has often been prickly because as the consummate reporter Malcolm is driven by the need to tell the story whatever the consequences. Nothing was “off the record” to him even when he gave assurances to the contrary. Malcolm wanted this book to be entitled “Representing Lindy” and to be my story. I persuaded him that the better story was to combine our stories and our insights. I accepted the suggested title “The Dingo Took Our Lives”. because it better reflects how this case has affected us, our immediate families and so many others who became involved.

This book and the letters reveal not only the pain so many of us felt but also how Lindy remained loyal and true. Lindy addressed all her letters not just to me, but included my wife, Cherie, and my baby son, Jaemes. She recognized before I did how much they would sacrifice and how much I would need their support to see this through.

Stuart Tipple