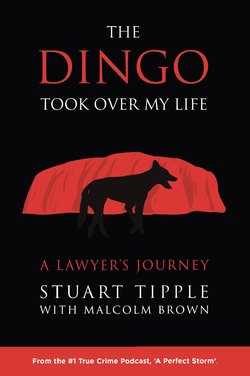

Читать книгу The Dingo Took Over My Life - Stuart Tipple - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Three THE DINGO POUNCES

ОглавлениеI hear your laughter in the night Enjoy it while you can The party’s just got under way Laugh awhile white man You weren’t invited to this place My heart is one huge stone But if you stay and eat and drink Don’t leave that child alone My spirit rises with the dusk As it has done before And when I come and take and steal I’ll leave you ripped and raw You’ll never laugh like this again My mark is stamped right through And anyone with any heart Will share your pain with you I hear your sad knock on my door I open it with shame Welcome to the desert Michael is your name The evil bone is pointed now The spirit has been sent Wait beside the fireside My thief is in your tent

– Lowell Tarling

The Chamberlain family arrived in Mt Isa in January 1980, and were only meant to stay there for 12 months. The plan was that the family would then move to Victoria where Michael would receive training in various aspects of the church’s health ministry. Mt Isa was a wealthy mining town founded after the discovery of one of the world’s richest deposits of copper, lead and zinc in 1923. Mining had been extensive, enormous wealth acquired, and as with all mining towns, the debris of mining, in particular copper dust, drifted across the landscape and deposited itself on every available surface. It settled onto the Chamberlain’s possessions, into their house, into the yellow Holden Torana Hatchback, and into Michael Chamberlain’s camera bag.

On 11th June 1980, Azaria Chantel Lauren Chamberlain was born at Mt Isa Hospital. Michael was reportedly making a nuisance of himself, insisting on taking photographs in the labour ward. The name Azaria was of Hebrew origin, and it meant “Blessed of God”. There was one incident, when Azaria apparently tumbled from a shopping trolley in a Mt Isa supermarket. However, a quick check with the family GP, Dr Irene Milne, showed she had not suffered any significant injury. In August 1980, the Chamberlains set off on a holiday to the Northern Territory. Michael loved the outdoors and wanted to go to the Top End. "I wanted to go to Darwin to catch barramundi," he said. "But Lindy had been to Uluru [the Aboriginal name for Ayers Rock, now in general use] before, at the age of 16, and wanted to go again. We meant to spend three days there, then go on to Darwin.”

The family arrived at Ayers Rock on Saturday, 16th August 1980. The motels at the site were rudimentary but there were facilities for aircraft and radio telephones were available, even though they were unable to be operated during certain times of the day. Perhaps the white, civilized, modern people who went there, fresh from air-conditioned luxury, really did not appreciate that they were coming into a place where there were fewer safety nets. People driving into the desert might run out of petrol, be nonplussed about what to do and find themselves in a situation where death is a distinct possibility. In remote areas, people with medical conditions could not just call for an ambulance. Someone bitten by a snake had a problem. Further north the problem was much the same. An out-of-towner found an inviting pool of water in the vast northern flatlands and plunged in, realising only in the last seconds of his life that he has chosen the domain of a crocodile. His body was later taken from inside the crocodile, in nine chunks. The Aboriginal people, so often disregarded, had a collective wisdom which had ensured their survival over millennia. But how many visitors referred to it?

The Chamberlains spent Sunday exploring the Ayers Rock area, during which Michael took the famous photograph of Lindy holding Azaria on the side of the rock. Michael and Lindy were in the camping area on the Sunday evening talking to two Tasmanian tourists, Greg and Sally Lowe, Lindy holding Azaria in her arms. Sally said later: “One of the few things that stands out in my mind after we were introduced to Lindy was, we asked what the baby’s name was. (Something I usually do to give you an idea if it’s a girl or boy – sometimes saved offending proud mums). The baby’s name was offered and so on. About this time Lindy had said how they had hoped for a girl and were so happy when the baby was a girl. The conversation stayed on babies for a while. Although we love Chantelle [Greg and Sally’s child], Greg and I wanted a boy. I think some mention was made of this. As I have some memory of Mike or Lindy saying something like – boys are easy, it’s harder to try for a girl (as though girls were special because of that). Our conversation went on to bushwalking, Tasmania and New Zealand and then on to Greg’s studies. Greg and Mike were talking about study at the time of Lindy’s return to the barbecue. Being more or less left out of the conversation, my ears were free.”

As they talked a dingo surprised them by leaping out of the darkness and grasping a mouse near their feet.

Greg Lowe, in a letter to Tipple a long time later, said he had offered Michael Chamberlain a beer which Chamberlain had declined, on the grounds he did not drink alcohol. “Lindy then offered the information that ‘a drinker doesn’t realise the effect it has on the family, that he ought to think not only the possible injury to his health but the effect this would have on his wife and children’s future’. (I think she disapproved of my casual attitude to beer-drinking),” he said. “This does indicate that she was concerned with future family health and welfare.” In the tent next to the Chamberlains’ tent, Bill and Judith West, a couple from Esperance in Western Australia, heard a canine growl which they took to be from a dingo, perhaps the growl of an animal warning another off.

On Lindy’s account she left the barbeque area with Azaria in her arms and Aidan beside her the and returned to the tent.After putting Azaria in the crib, Aidan announced he was still hungry.Lindy went to the back of the car, got a can of baked beans out and returned to the barbeque area with Aidan. A minute or so after that, Michael Chamberlain, Sally Lowe, and another camper, Gail Dawson, heard what they thought was a baby’s sharp cry from the direction of the tent. When Michael remarked on it, Lindy went to the tent to have a look, and according to her account, saw a dingo come from the entrance with something in its mouth. She could not make out what it was carrying. Her first instinct was to go into the tent to check the baby. The baby was gone. She raised the cry which transformed her from a housewife to a headline: “A dingo’s got my baby!”

Michael and the Lowes immediately ran to the tent. In his later account in a letter to Stuart Tipple, Greg Lowe said his wife Sally found a pool of blood – she estimated 8 by 16 square centimetres in area – on the floor of the tent. The blood was spread over articles of clothing, sleeping bags and other items. Writing to Tipple years later, Sally said: “I know there were several spots and I saw them in front of me and to the right. The immediate priority on the night, was to find the baby. Michael Chamberlain and Greg Lowe went in the direction the dingo was thought to have gone.” Greg said: “Then we extended the search pattern to a grid on the whole of the sand hill area to the east of the tent and other searching. I indicated to Mike that night that if I were a dingo, I would do a circuit and wait in the bushes near the scene of the tent. We searched extensively ‘close to home’ in quite a large radius.”

Other campers went immediately to search the sand hills, and were soon joined by rangers. A local Aboriginal elder, Nipper Winmatti, on his later account saw dingo tracks outside the tent and he followed them. He said he saw blood in the sand. “We first tracked the dingo from the back of the tent,” he said. “It came around and went inside the tent.” He had followed the dingo tracks towards the tiny Ayers Rock township, which comprised a collection of motels and other buildings. The dingo had apparently been carrying a burden, but the tracks had petered out in the spinifex. Others saw evidence of dingo tracks in the sand. The head park ranger at Uluru National Park, Derek Roff, went tracking that night with a local Aboriginal, Ngui Minyintiri. They followed the tracks and drag marks for 15 metres before losing them, then traced them back to a point 17 metres from the tent and in direct line with the tent. He had backtracked to within 12 metres of the road running beside the camp site.

The Chamberlains stayed near the tent in the freezing cold for several hours waiting for news. About midnight they were persuaded to go to a nearby motel. A local police officer and the camp nurse, Bobby Downs, helped them transfer clothing and bedding from the tent into the car and the police four-wheel drive vehicle before driving them to the motel. Greg Lowe told Tipple later that they might have unwittingly transferred some of the spilled blood onto their clothing. The tent remained as they had left it. Greg Lowe posed the question in a letter to Tipple much later: “Could any of these blood-stained articles … and effects account for any alleged traces of … blood in the car, especially if they were bundled into the car before the Chamberlains left for the motel?”

Word went out nationally that a baby had been taken by a dingo at Ayers Rock. Reporters scrambled to get there. People scratched their heads and wondered. A dingo?

On the Sunday morning, a motel employee at Ayers Rock, Elizabeth Prell, took breakfast to the Chamberlains. She later said she saw a blood stain on a sleeping bag that had been removed from the tent. The stain was “about three inches” in diameter. At Ayers Rock, Aboriginal trackers scoured the area further out from Ayers Rock. They found dingo tracks at the base of Ayers Rock, then argued among themselves about their significance. Tracks made by the searchers on the night and next day complicated things. At the tent, there seemed much clearer evidence that the dingo had been there. Constable Frank Morris, the police constable stationed at Ayers Rock, found dingo tracks along the tent. He also saw paw prints when he lifted the bottom edge of the tent where it had ballooned out near where the bassinet stood.

Two police officers who arrived from Alice Springs, Inspector Michael Gilroy and Sergeant John Lincoln found paw prints immediately behind the tent together with a wet patch in the sand which they thought might have been saliva. They took photographs and a sample of the wet sand but the photos did not turn out and the wet sand was never properly tested. Gilroy looked carefully at the baby’s bassinet and found animal hairs which he thought might be dingo hairs. A camper, Murray Haby, found an impression in a sand dune near the camping area which appeared to him to have been made when a dingo put something down. He showed it to Derek Roff. The imprint on the sand reminded Roff of crepe bandage or, as he said later in evidence, “very consistent with elastic band sort of material". It was a perfect description of the material of the jumpsuit Azaria was wearing.

That, surely, should have been enough. A dingo had been there. As in all police investigations, the first thing to look for is what the perpetrator has left behind. In this case it was tracks, the drag mark and the imprint of fabric on the sand. That in combination with, the dingo growl, the baby’s cry and Lindy’s report of seeing a dingo, should have been enough. Of course, in the initial period, it was. The principal objective now was to find the baby – or more probably its remains – and, if possible, the dingo.

Word was now well and truly out. Lindy’s parents, Cliff and Avis Murchison, were retired and living in Nowra on the NSW south coast. Alex Murchison was working for Shoalhaven Shire Council, as it then was, laying sewerage pipes, when his foreman approached and told him the news.

At Ayers Rock, the searching continued all Monday, during which Michael was at pains to get black-and-white photographic film so he could take pictures for a newspaper that had contacted him. His actions were, he said later, to warn people what might happen, but some people even in those early stages were mystified by his actions, wondering about his priorities. On the Tuesday, Aboriginal trackers followed dingo tracks for six kilometres from the campsite into sand hill country but found it doubled back and then the tracks became lost near the reservoir at the township. That day, Michael and Lindy Chamberlain, left for Mt Isa. There were still people searching and their decision to leave raised eyebrows. Michael and Lindy had decided there was no hope of finding the baby alive. Michael Chamberlain, having a traumatised family, decided his priority now was to look after them.

In the meantime, police packaged up the Chamberlains’ tent and its contents and put them in a cardboard box to be taken to Darwin for scientific examination. It was, in retrospect, a clumsy way of handling evidence, some of which, like any blood spray on the tent wall, was fragile, hard to see and easily destroyed. It must also be taken into account that all this had happened in a remote area. Distance was difficult. Communications were difficult. The radio telephone cut out for several hours each day. At that stage there was only the vaguest thought that one of the family might have been responsible for the child’s death, but the second safeguard, the expertise and professionalism of investigating police, was starting to fail.

The Chamberlain family arrived at Mt Isa and was now the centre of attention. Lindy’s parents, Cliff and Avis Murchison, and Lindy’s brother, Alex Murchison, went to Mt Isa. Alex said: “I remember mum held up the space blanket and there were muddy paw-prints on it. I could see the tiny pin-holes of light shining through where the dingo’s claws had gone through the space blanket. There was mud on the paw prints, the soil was still caked on.”

At Mt Isa, the gossip and rumour-mongering had begun. Members of the local SDA Church rallied around the Chamberlains. Lindy was also consoled by a close friend, Jennifer Ransom, and told her that she would be reunited with her baby in Eternity. According to Mrs Ransom, Lindy said: “I know that if I am true to the Lord for the rest of my life, she will be back in my arms as pure and beautiful as when I put her down to sleep”. A dry-cleaner at Mt Isa, Jennifer Prell, said Michael Chamberlain had brought in a sleeping bag which had “seven or eight” stains on it and had said he wanted it cleaned. The stains, potentially, constituted more evidence that blood had been spilled in the tent.

The Chamberlains’ tent arrived in Darwin at the bottom of a cardboard box on Thursday 21st August. The box was handed to Myra Fogarty, a police officer who had had three months’ experience in forensic work but no formal training. Her superior, Sergeant Bruce Sandry, told her to look for hair and blood. Fogarty unpacked the box and examined it. She was not told about any blood spray on the tent wall and did not see it. She assumed she was looking for human hairs and plucked some of her hair out to use as a control. She did not do any “lifting”, using adhesive tape to pick up what particles there might have been on surfaces in and on the tent. What she did say when she made her report was that there was less blood than she would have expected had there been a dingo attack. That was a careless comment on her part. It carried a number of assumptions, principally that the dingo would have torn the baby’s flesh and tossed it around in its jaws, spilling blood. If a dingo had snatched a baby in the way it apparently did, it would more likely to have been quick, a second or two. The baby would then have been whisked away by the dingo. Its teeth would all probability have occluded the blood in the wounds, preventing much of it from spilling. Her comment about expecting more blood was to rebound on her.

The next development came on Sunday, 24th August, when a tourist, Wallace Victor Goodwin, found Azaria’s jumpsuit, singlet and nappy at the base of Ayers Rock, 3.5 kilometres from the campsite. It was 20 metres from a dingo lair, though at the time not even the rangers knew the lair was there. There was no sign of the body. Goodwin reported the find to Constable Frank Morris. Morris, moved the clothing before photographing it to see whether there was anything inside it. In hindsight, a lot of controversy would have been avoided if the area had been sealed off and everything photographed before it was touched or moved. Morris must surely have wished he had done that. To be fair to him, the suggestion there had been a murder was a long way off. After examining the clothing, Morris laid it out in the way he thought he had found it. Goodwin did not agree with the way Morris did it. He said the description of the clothing, “neatly folded”, was not accurate. Morris claimed the jumpsuit was basically open except for a couple of studs at the bottom which he undid. Goodwin heard Morris ask Roff whether there were other dingo lairs in the area and Roff had said there were three. The second safeguard, preserving scientific evidence of a dingo attack, was failing.

Back in Mt Isa, Michael and Lindy Chamberlain started to hear the first poisonous talk about them, which was to rise to a crescendo. There were stories floating around that the SDA church practised black magic, or child sacrifice. The national mood itself became darker when on 29th August, Dr Eric Milne, brother of Lindy Chamberlain’s doctor, Dr Irene Mile, rang the police and told them that “Azaria” meant “Sacrifice in the Wilderness”. It was enough for the NT Police to send Constable Jim Metcalf, to the Mitchell Library in Sydney to research the meaning of the name. He came up with nothing but the rumour persisted.

The stories kept coming – that Azaria had been kidnapped by Aboriginals, or for that matter aliens. One extraordinary story was that Lindy had spear-tackled Azaria in the Mt Isa Supermarket, that a blood transfusion had been ordered on the baby and the Chamberlains had refused because the SDA church did not believe in blood transfusions, and that the baby had died and the dingo attack at Ayers Rock had been a charade, with SDA accomplices at Ayers Rock to back up her story. There was not a scrap of truth in this, though Azaria had had a tumble from a shopping trolley. The Chamberlains were at a disadvantage because of their religion. When questioned on television about the supposedly neat state of the baby’s clothing, Lindy said: “If you’ve ever seen a dingo eat, there’s no difficulty at all. They never eat the skin. They use their feet like feet like hands and pull back the skin as they go – just like peeling an orange.”

If only she had not said that! It caused audiences across the nation to recoil, at the supposedly clinical way in which she spoke about her lost baby. What Lindy said was accurate enough. Anyone who has ever owned a dog would know that dogs do not eat like pigs. They are quite delicate, even fastidious, eaters. But such was the developing hysteria that Lindy’s remarks did not go down well. There were other suggestions being put about, that the mother had done away with the baby, that it had been buried in the sand, dug up and reburied, and the jumpsuit placed near where dingoes were known to be. The Chamberlains were not helped by the findings of David Torlach, an agricultural scientist, called by the police to analyse soils at Ayers Rock to find the source of sand found in the jumpsuit. He found that soil in the campsite area had the same acidity as sand in Azaria’s jumpsuit and was different from the sand at the base of Ayers Rock.

The rumours escalated. When Malcolm Brown, as a reporter on the Sydney Morning Herald, rang Lindy at Mt Isa on 3rd September 1980, Michael had resumed his ministerial duties and was on a four-day conference for SDA ministers at Townsville. She said Aidan had come home crying from school, after receiving cruel jibes from other children. A friend’s phone had been “running hot” with unsympathetic inquirers. “The latest rumour going around is that my husband has been charged with murder, and that the baby was a sacrifice for our religion,” she said. “People say this memorial we want put up to Azaria at Ayers Rock is part of this sacrifice thing.” When she went shopping, and was unrecognised, she heard the gossip. “They’re liking the case with the Jonestown massacre and with the Spear Creek murders at Mt Isa 12 months ago,” she said. “I think three people were killed then. We were not even in Mt Isa. People say Azaria was sickly. They even say she was spastic. She wasn’t.” In October 1980, police conducted an interview with Aidan Chamberlain at Mt Isa. While they were doing that, Constable Barry Graham searched the Chamberlains’ car using a Big Jim torch. He reported: “I examined the interior of the vehicle, including the front and rear sections, seats, console, dashboard, glove compartment and hood. I did not find any suspicious staining in those areas.” He later admitted that he was also looking for a possible weapon and found none, not even scissors. His report would not be disclosed till years later. Neither the Chamberlain’s nor their legal team were told of this search until the Royal Commission years later.

Michael and Lindy Chamberlain gave statements on 1st and 2nd October. On 15th December, represented by an Alice Springs solicitor, Peter Dean, and later Phil Rice QC, from Adelaide, they appeared at the coroner’s inquest before Denis Barritt. Barritt was a genial 54-year-old former Victorian detective, then barrister, who had come to the Northern Territory 2-1/2 years before as a magistrate and coroner. He was from several perspectives the right man for the job. He had taken pains to educate himself in traditional Aboriginal law and culture. Interviewed by Malcolm Brown, he said that on one occasion an Aboriginal youth had stolen a car in Alice Springs and driven out towards an outstation in the desert. When he was a long way out, he had heard a noise in the back seat, had a look and found a little boy had been sleeping there. The youth brought the boy back to Alice Springs. He tried to get away but was caught. Barritt said: “The rules of the bench prevented me from stepping down and hugging that young man! He could have just ditched the boy somewhere. But he did the right thing.” Barritt did not say what penalty he had imposed for illegal use of the car, but it would probably have been a good behaviour bond, possibly with no conviction recorded. Barritt had a similar common-sense view towards the evidence that was now presented to him.

Appearing in the witness box, Lindy Chamberlain was well aware of rumours and suggestions that she had been involved in the baby’s death. She told Ashley Macknay, counsel assisting the coroner, that she could not entertain a scenario other than a dingo taking the baby. She said: “To consider that it was done with something other than a dingo brings in such a range of coincidences with split second timing that it seems impossible.” Greg and Sally Lowe gave evidence of what they had seen and heard, all exculpatory of the Chamberlains. Bill and Judith West gave evidence of hearing a dingo growl before Lindy raised the alarm.

Six-year-old Aidan Chamberlain’s statement totally supported the account his mother gave. He said he had been with his mother during the entire period from Lindy Chamberlain being at the barbecue area with Azaria and the moment she had raised the alarm. He said: “While we were in the tent, mummy put bubby in the cot and then I went to the car with mummy and she got some baked beans. I followed her down to the barbecue area. When we got to the barbecue area mummy opened the tin of baked beans and daddy said, ‘Is that bubby crying?’ and mummy said, ‘I don’t think so’. Mummy went back to the tent and said, ‘A dingo’s got my baby!’.”

All the evidence was pointing to a dingo attack. Aidan’s evidence, together with that of Sally Lowe, provided a barrier to any suggestion that there had been foul play. But the ugly rumours would not go away, and the yobbo mentality had been stirred. When the inquest resumed on 9th February 1981, after the Christmas break, it was decided, in the light of a number of anonymous telephone threats that had been made against the Chamberlains, that they should have a bodyguard. The man assigned to the task, Constable Frank Gibson, might have been under instructions to pick up anything about the Chamberlains that could be used in evidence. Whether that was true or not, Gibson became very positive in his attitude towards the couple. Others never became positive. The fact that the Chamberlains were “different” became the focus of national attention. Pastor Wal Taylor, the SDA Church’s legal liaison officer, said: “Had this involved the Methodist or Baptist Churches, there may not have been the same misunderstanding. There are the mainstream and fringe churches and many people have tended to put us on the fringe.”

In the resumed inquest, the focus was on scientific evidence. From the start, the Chamberlains were at a disadvantage. A South Australian forensic biologist, Andrew Scott, confirmed there been a spray of blood on the tent wall. That was critical evidence that the baby had been attacked in the tent. By the time Scott tested the area he failed to get a positive result, possibly because the material had been affected by the waterproofing compound in the tent wall. Scott concluded that it was probably not human blood.

Other evidence potentially raised suspicion. Rex Kuchel, a forensic botanist from Adelaide, a part-time scientific adviser to the South Australian Police, had examined sand and vegetation embedded in the jumpsuit. He had been looking for pulled threads which he expected had an object covered in the jumpsuit material been dragged through vegetation. Rather, he thought, the jumpsuit – presumably with the baby’s body in it – had been buried in sand hills east of the campsite, then dug up and carried to where it was found at the base of Ayers Rock. In his experimentation, he had arranged for an effigy of a baby to be dressed in a jumpsuit and dragged through vegetation at Ayers Rock. The result, he said, was quite different. It was pointed out by Ashley Macknay that he had made his observations taken from pictures by a professional photographer rather than direct observation. There had been damage to the undergrowth by the person dragging the effigy. But he had not been on the spot and had not been able to determine what other people had been through that area.

Kuchel agreed under questioning that wild animals, and even domestic animals, sometimes buried their prey. But if the clothing was buried, where? Dr Barry Collins from the Minerals Department of South Australia said that 90 percent of the soil found on the baby’s clothing was consistent with the soil found at the site of the Chamberlains’ tent and 10 percent from the area round Ayers Rock. That seemed to support the burial theory. Had a dingo done the burying? Or had it been done, for whatever reason, by a person or persons? Sergeant Barry Cocks, of the South Australian Police, fresh from his involvement in the Edward Charles Splatt case, gave evidence supporting human intervention. From ruptures in the jumpsuit, he had concluded that a “bladed instrument”, a knife perhaps, or a pair of scissors, had been used. Kenneth Brown said he had examined the clothing and also examined dingo skulls and had concluded that a dingo’s teeth could not have done the damage to the baby’s clothing. So that laid it squarely on the line that there had been human intervention. Had it been someone at Ayers Rock? Or had it been the parents? And if so, why? Was it to fabricate evidence of a dingo attack?

A dingo expert, Dr Eric Newsome, senior researcher at the CSIRO Wildlife Research Division, said it was unlikely a dingo would have taken the baby but he did not discount the possibility. He said crows or eagles could have taken the clothing to where it was found at the base of Ayers Rock. That left open the possibility that a dingo had taken the baby but that person or persons had intervened afterwards. Another possibility, never brought up, was that in the week since Azaria disappeared and when the clothing was found at the base of Ayers Rock, an animal might have got at it and moved it of its own accord. Nevertheless, Macknay was not persuaded by much of the scientific evidence. In his submissions to Barritt on 19th February, he was particularly critical of the evidence of both Kuchel, Cocks and Brown, according to a report of proceedings by the Sydney Morning Herald. “What has happened, I submit, is that [they] were in pursuit of finding points to support the theory that no dingo had any part to play in this,” he said. The three rejected that suggestion, maintaining that at all times they were professionally objective.

Denis Barritt, satisfied that the baby was dead and that she had been taken by a dingo, decided that the issues raised by the suspicion and gossip surrounding the case should be addressed. He abided by a request from a television crew to telecast his findings nationally. Appearing before an international audience on 20th February 1981, he said neither of the parents, or for that matter their two sons, had had anything to do with the baby’s death, but there had been “human intervention” in relation to the damage to the clothing and the way it was handled and deposited after the dingo took the baby. Barritt accepted the primary evidence that a dingo had been responsible. He did not find the scientific evidence to the contrary convincing. Of Kenneth Brown’s evidence, that a dingo had not caused the damage to the jumpsuit, he said Brown had admitted he did not have expertise in bite marks made on clothing, so it would be “dangerous to accept his evidence in that regard”.

Barritt was severely critical of the police, whom he believed had been biased in their investigation, a bias fuelled by a disbelief in Lindy’s story. He was particularly harsh on Myra Fogarty, whose evidence on finding less blood than might be expected from a dingo attack had been in his view a tacit attempt to advance the murder theory. Constable Fogarty had not been taught the principles of scientific observation and had been given a critical examination which was beyond her competence. Supervision in the section, Barritt said, had been “negligent in the extreme”. Sergeant Sandry, he said, appeared sceptical of the dingo theory when he interviewed dingo experts, according to a report of the finding in the Sydney Morning Herald. Sandry and Fogarty had, like Morris, not appreciated just how critical what they did would become. In different circumstances their performance would not have been remarked on at all. In professional terms, they were in the wrong place at the wrong time. But Barritt was adamant that the police should have done better. “Police forces must realise, or be made to realise, that courts will not tolerate any standard less than complete objectivity from anyone claiming to be making scientific observations,” he said.

These deficiencies in the police investigation had compounded the problems of the Chamberlains who had been subjected to “probably the most malicious gossip ever witnessed in this country”. Barritt said he had had advice from a Hebrew expert that “Azaria” meant “With the Help of God”, and that the name for “Sacrifice in the Wilderness” was similar-sounding but different. Another meaning for Azaria given at the inquest said it meant “Blessed of God”. The confusion probably arose because directly under the definition of “Azaria” was “Azazel”, which meant “Devil”, “Bearer of Sins”, or the name of a demon in the wilderness to whom a goat was sent.

Barritt said the NT Parks and Wildlife Service had a responsibility to protect human life, particularly in circumstances where there had already been dingo attacks on children. The service had a responsibility to protect children coming into national parks and where there were dangerous animals, they should be eliminated from parks or at least those parts where there was a high frequency of visitors. He acknowledged that the service had a responsibility to preserve wildlife. If there were laws forbidding the destruction of particular wildlife, then the inherent danger of these creatures should be publicised. The death of a baby, he said, was a high price to pay for conservation. And that, it seemed, was that. The safeguard, of the balanced, objective look of an experienced coroner, had worked.

Michael and Lindy Chamberlain emerged from the courthouse and displayed an enlarged picture of Lindy holding Azaria, then returned, it was hoped, to resume their lives as an SDA pastor and wife. Azaria’s death certificate registered at Alice Springs on 6th March 1981 read: “Inquest held 20 February 1981 D.J. Barritt, Coroner. Severe crushing to the base of the skull and neck and lacerations to the throat and neck.”

In Gosford, Stuart Tipple had followed the case with intense interest. He was aware of the rumours that there had been foul play. He did not think Michael would have done anything like that, or been party to it in any way. It was with “a feeling of great relief”, he said later, that he heard Barritt’s finding which exonerated the parents.

Of course, the inquiry was not over. If, as Barritt said, there had been human intervention, then who was it? The person or persons responsible could face several charges: of interfering with a corpse, unauthorised burial and failure to report a death. It was a matter for the police to answer that unsolved question. The NT police held onto the jumpsuit and other exhibits from the inquest. A senior police officer at Alice Springs said, quite justifiably: “The hearing can be reopened in the future if fresh information comes to light.” There were other factors too. The NT Police had their noses totally out-of-joint. The NT Conservation Commission did not like his remarks either. The NT Government appeared anxious to demonstrate it could handle its affairs as well as anybody else. The case acquired a political significance which it would never have had the same event occurred in New South Wales, Victoria or any other states. Cases like the Ananda Marga prosecutions or the Blackburn case in New South Wales, or the Cessna-Milner case which involved allegations of improper conduct, had embarrassed the governments but had hardly threatened their hold on power.

In Darwin, Myra Fogarty resigned from the NT Police Force. In Adelaide, Kenneth Brown wanted to continue the inquiry. He later denied that he had felt humiliated and wanted to vindicate himself, and to be fair the criticism of him was not damning. It was just a point made from the bench about one corner of his professional expertise, but it was stated in front of an international audience. He did think more could be found out, and perhaps he should seek the advice of a world authority, Professor Cameron, who had invited Kenneth Brown to work in his laboratory in 1975. It would also be possible to consult Bernard Sims, who lectured in forensic odontology at the same college, and who had written book, Forensic Dentistry, which had been regarded for years as an authority on the subject and which Brown himself had referred to in his work in South Australia. Brown asked the NT Government for the baby’s clothes, and he received them on 27th May. He travelled to Britain with the clothing. He was going to what he might have thought was the forensic “Privy Council”, the London Hospital Medical College, to have matters reviewed. The safeguard of Barritt’s finding, the common-sense view of a genial worldly-wise former frontline detective, was now under threat.