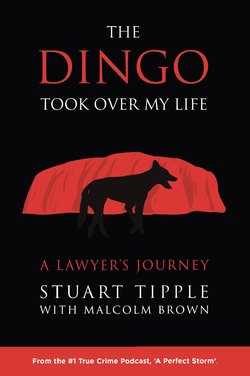

Читать книгу The Dingo Took Over My Life - Stuart Tipple - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One GUESS WHO I MET ON THE

WAY TO THE SHOPS!

ОглавлениеTo be, or not to be – that is the question Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune Or to take arms against a sea of troubles And by opposing end them.

– Hamlet

On a fine sunny morning in early September 1981, lawyer Stuart Tipple, was walking along the main street of Wyong on the central NSW coast. At 29 years of age, six years out from Law School, he had no particular worries. He had a fine, sun-drenched lifestyle, a beautiful wife, Cherie, and a good employer: Brennan and Blair, Solicitors, Gosford. A practising Seventh-day Adventist (SDA), Tipple had already established top-level contact with senior members of his church. Among other things he had sat on the board of the SDA Church’s hospital, “The San”, at Wahroonga, in Sydney’s Northern suburbs. Alongside him on the board was Dr Jim Cox, president of Avondale College, Cooranbong, the SDA tertiary education establishment in the Lake Macquarie hinterland on the Central Coast. Tipple in his professional life had taken on tough briefs, as a public solicitor, handling the affairs of hardened criminals. Having seen enough of how that world worked, he had then established himself in a good provincial practice, far enough from Sydney to escape the bustle but near enough not be left out in the sticks. He had fallen on his feet.

There was a cloud, fairly remote, on the horizon: the Azaria Chamberlain case. It interested but it did not affect him. Being a Seventh-day Adventist, his attention had naturally been attracted to it, and he had met SDA Pastor Michael Chamberlain as a boy in New Zealand. At that point he viewed it as someone who might see a storm in the distance. Little did he know that that storm would break over him, and that for decades to come he would be at the centre of a disaster.

At Ayers Rock in central Australia, on 17th August 1980, a nine-week old baby, Azaria Chantel Loren Chamberlain, had disappeared, reportedly taken away in the jaws of a dingo. It had been such an unusual event, seemingly unprecedented and not expected of coyote-type creatures whose normal response to human intrusion was to scuttle away. From the outset there had been doubt, which had quickly evolved into ugly rumours about the parents, SDA pastor Michael Leigh Chamberlain and his wife, Alice Lynne “Lindy” Chamberlain. It was suggested that one or both had murdered the baby and disposed of it. Why on earth she would have done that was a matter of intense speculation. Perhaps the baby had been deformed. Perhaps it had been a human sacrifice, something to do with their religion.

Intense publicity sharpened curiosity, along with the reactions of both parents who appeared on television struck the public as odd. They had not reacted in the way grief-stricken, traumatised parents were expected to react. Lindy’s seemingly clinical, dispassionate account of how the dingo might have eaten her baby – “peeling it as you would an orange” – did her and her husband no good at all. Denis Barritt, the coroner found that a dingo had taken the baby. The death certificate filed out soon afterwards said: “Inquest held 20 February 1981 D.J. Barritt Coroner. [Cause of death] severe crushing to the base of the skull and neck and lacerations to the throat and neck.”

Barritt had decided to deliver his verdict on national television, because he felt that the hysteria which had given rise to such ugly rumours should be put to rest for good. But he had not succeeded. Barritt’s finding, that a dingo was responsible for Azaria’s disappearance and death also included a finding that there had been “human intervention” in relation to disposal of the baby’s jumpsuit, booties and nappy, found at the base of Ayers Rock a week after Azaria disappeared. He had based that particular finding on evidence that the jumpsuit appeared to have been cut by a bladed instrument. That element of his finding guaranteed, quite rightly, that the inquiry was not over. If there had been human intervention, then who was it? And why?

Tipple, as he walked along the Wyong street that September morning, wasn’t thinking about those things. Then Michael Chamberlain turned up in person, in helmet and leathers and on a motorcycle. They greeted each other and chatted for a time. Inevitably they had talked about the events at Ayers Rock and the inquest. At the end of the conversation, Chamberlain said: “Well, if I ever need a lawyer ….”

Michael Chamberlain returned to Avondale College, where he and Lindy had taken up residence after the coroner’s inquest. Though they had been exonerated over the loss of the baby, that terrible event, the rumour and innuendo and the inquest already affected them. It was considered appropriate that Michael Chamberlain leave his posting as an SDA pastor at Mt Isa in western Queensland and return to Cooranbong where he and Lindy could do some more study. Michael intended to do a Master’s degree in physical education through Andrews University, an SDA establishment in Michigan, USA. With Michael and Lindy were their sons, Aidan, six, and Reagan, four, both of whom had been through the trauma at Ayers Rock.

On Saturday, 18th September 1981, about two weeks after the meeting between Tipple and Michael Chamberlain in Wyong, the storm clouds burst. It started at 8.10 am when police knocked on the Chamberlains’ door at Avondale College and Aidan opened it. At the same time, police swooped on the homes of people, in Victoria, Western Australia and Tasmania, who had been witnesses on the night of 17th August 1980 and whose testimony had supported the dingo story. Armed with new scientific evidence and an expert opinion that the baby had in fact been murdered, probably by having its throat cut, the police were on the hunt.

The evidence they were now looking for would come from the Chamberlain’ home, and their 1977-model yellow Torana Hatchback. They picked up the Torana at a Central Coast repair shop. What the primary witnesses had said of the events on the night was now to be reviewed. The police took more than 400 items from the Chamberlains’ home. They picked up a camera bag which they thought Michael had taken to Ayers Rock. Michael told them it was not the right one and gave them the bag he had taken. The seized items were packed up and sent to the NSW Health Department Division of Forensic Medicine for analysis. Working there was Joy Kuhl, a Master of Science, who was briefed to do the analysis.

News of the raids leaked out and media helicopters started buzzing over the Chamberlains’ home at Cooranbong. Michael and Lindy telephoned Jim Cox, who immediately thought of Stuart Tipple. He was unable to reach Tipple just then but he had an instinctive belief in him.

In Alice Springs, Denis Barritt received a telephone call from the NT Solicitor-General, Peter Tiffin, telling him that new evidence had come forward and that Barritt’s findings were to be quashed and they had briefed a barrister to represent him. Barritt immediately contacted the barrister, Michael Maurice. He told Maurice he had not been acquainted with the content of any new evidence that might have been available. Barritt said Michael and Lindy Chamberlain ought to have the opportunity to be represented. He had no objection to his findings being set aside if fresh evidence became available, provided it could not have been discovered by due diligence before his own inquiry. Maurice was informed he could not have access to the new information unless he would undertake not to disclose it to Barritt. Maurice felt duty-bound as counsel to discuss all material with his client. Being unable to do this, he withdrew from the case. Barritt’s court orderly, Bill Barnes, might have been a little disappointed by the turn of events. He had caught a bucketing from officialdom after Barritt’s inquest for presenting the departing Chamberlains with a bouquet of flowers. (Not done, old chap! Court officers must be seen to be detatched!)

In Tasmania, Sally Lowe, who had met Michael and Lindy Chamberlain at the barbecue area of Ayers Rock on the night Azaria disappeared – and had testified that she had heard the baby cry after Lindy took her away and had returned to the barbecue area – was now under intense pressure in the renewed investigation. Under special scrutiny was how long Lindy had been away from the barbecue area. That was now a critical question, because on a possible scenario now being taken seriously by police, Lindy had used her time away from the barbecue area to kill the baby, possibly by slashing its throat. She had then on that scenario secreted the body, washed her hands, changed her clothes and come back to act as though nothing had happened. Then, she had acted out a charade pretending she had seen a dingo take her baby.

Sally Lowe told Tipple later that when interviewed by the police, she had said Lindy had been away from the barbecue area for “a few minutes”. The police officer had said: “Surely it would have taken that long just to walk there and back.” The police officer had suggested Lindy might have been away “10 or even 15 minutes, or longer”. Sally had said Lindy might have taken a few minutes to get to the tent and to put the baby to bed. The police officer had said: “Was it 10 or 15 minutes?” Sally said: “Well, I knew it was not as long as 15 minutes, it was less than 10 minutes.” Sally told Tipple. “And so, it went on, until I finally agreed to six to 10 minutes.” The questioning had made Sally Lowe feel very uncomfortable. “Not wishing to go back on anything I had made in a statement, I felt it best to say – ‘a very short time’,” she said.

On Sunday 19th September 1981, the Northern Territory’s Chief Minister and Attorney-General, Paul Everingham, announced that a new investigation had begun into the disappearance of Azaria Chamberlain, based on a report by leading British pathologist, Professor James Malcolm Cameron, using technology not available in Australia. Cameron had concluded, from an examination of the baby’s jumpsuit, that the child had been murdered, possibly by someone slitting its throat, and possibly holding it upright while the deed was done. It was later to emerge that there had been an extraordinary effort to get evidence to support Cameron’s contention, all done in secret, with the Chamberlains blissfully unaware. Cameron had visited Australia and meeting, Paul Everingham and the NT Police Commissioner, Peter McAulay, in Brisbane. After Cameron had presented his findings, the inquiry was reopened. They had had little option. Police regrouped in a new investigation, code-named “Operation Ochre”.

Stuart Tipple received a telephone call from Lindy Chamberlain on the Sunday, 19th September. He had never met her but she had been told about him by Jim Cox and by Michael. Tipple drove the 30 minutes from Gosford to Avondale College to meet the Chamberlains in the couple’s small and very cluttered cottage. Peter Dean, who had represented the Chamberlains at the coroner’s inquest, had flown from Alice Springs and was already there. The Chamberlains were, naturally enough, stunned by what was happening. They were, Tipple said later, “in a state of disbelief”. “I suppose like anything you wonder what is going to happen next,” Tipple recalled years later. “You wonder what sort of people they really are, what the evidence is against them. I was sensitive to the fact that I did not want to tread on Peter Dean’s toes. I saw my role as advisory. I had no idea the case was going to take up the rest of my career.” Of Lindy, he said: “She was smaller than I imagined, quite petite. I think the other thing she had a harsh voice which surprised me. But I don’t think anyone realised the seriousness of the situation. Certainly, the Chamberlains did not. Why was the case reopened? Obviously, the Chamberlains were “in the gun” and we needed to get information before we could give them advice. Then you do what you always do. You say to your clients don’t volunteer anything, let us find out what the police want. We’ll ask for any questions they have to be in writing and sent to us.”

And what, pray tell, was the alleged crime? It was alleged that a mother, for whatever reason, perhaps in a sudden onset of depression, overstressed perhaps, had killed her baby. A case of infanticide – an event sadly not uncommon, for which in a civilised community mothers are called to account but usually treated with at least a degree of compassion. Surely a crime such as this did not justify going to the other end of the world for expert advice! Would the police and administrators have gone to this much trouble had this occurred in New South Wales or Victoria? Here, it was suspected, the Territory was out to show it could conduct its own affairs and handle even the most difficult criminal investigations. It had the resources of State at its disposal to investigate the case and prosecute. It had police, lawyers and forensic scientists. What did the Chamberlains have? Limited finances and a couple of solicitors. They were two people against an army, and the weight of that army’s offensive was likely to brush aside their defences and convict them.

For Tipple, who would for a time be working with Peter Dean, it was to be a massive leap. He would embark on a journey that would take him far and away beyond the comfort zone of provincial solicitor. Lawyers, of course, are required to gain rapid expertise in many subjects – whatever comes through their door. The characteristics of wild animals do not come often.

The dingo, an animal estimated to have come to Australia anything from 3,000 to 12,000 years ago, supposedly related to the Indian Pale-Footed Wolf, was the apex predator in Australia. From colonial times, dingoes attacked livestock and were hunted and killed. Attacks on humans were rare but not unknown. The Sydney Morning Herald carried a report in 1902 that an Aboriginal child had been attacked and killed by a dingo. In more recent times, information came to hand that a dingo had killed an Aboriginal baby at Alroy Downs station in the Northern Territory and run off with it but it had not been reported to the authorities because of the legal implications of not reporting a death. Wary by nature of humans, they could be domesticated to some extent, and certainly could become more relaxed in human company over a period of time. But in the context of what was about to happen, when the dingo – a theoretical one in the eyes of the sceptics – was to take centre stage, there was another factor that was far more important. Could they become so relaxed that they could kill a human child?

There was abundant evidence that dingoes had become bolder at Ayers Rock. A Sydneysider, piano teacher Anne Hall, of Beecroft, would say that when she and her husband had visited Ayers Rock in 1979, there were “dingoes everywhere”. Julian Carter, of Scottsdale, Tasmania, was to say that on two nights in June 1980 he had been camped there and had seen “a pair of dingoes moving through our tent area, but not both together”. He said: “I recall coming out of the shower block and seeing one dingo backing from a tent dragging a carry bag. When I got to the tent area (only a few metres from the showers), it scared before I yelled anything, and it ran in an arc and disappeared into the undergrowth in the opposite side of the shower lock. The second dingo ran from another tent, following the first in the same direction into light undergrowth. I yelled after them to hurry both along. All our 23 pyramid tents had door-flaps fixed back and open to permit airing. Apart from half a dozen of my group in the showers, the camp was deserted at that time. The dingoes don’t like the presence of people. We did notice these dingoes at a distance earlier and also at a distance on a couple of other occasions while we were at the rock camping ground. Some of the kids were tempted to throw stones at them, but were stopped from doing this. We didn’t have any more experience of the animals being in or near the tents. From, later that afternoon we kept all tents closed wherever the bulk of our party was away sightseeing and left one person on the tent site all the time, for reasons mentioned above.”

On 22nd June 1980, a Victorian family at Ayers Rock had the traumatic experience of seeing a dingo drag their six-year-old daughter, Amanda, from the family car. Amanda had cried out and the family, intervening, had chased the dingo away. The father, Max Cranwell, reported the matter to Ayers Rock ranger Ian Cawood, who said the dog was “Ding”, a semi-domesticated dingo that would have to be destroyed. Cranwell said later that Cawood had said words to the effect that he had shot Ding. Evidence of this particular animal came before coroner Denis Barritt, though not the attack on Amanda Cranwell, which was not on record at the time. Cawood told Barritt that there had been a troublesome dingo, called “Ding” born at Ayers Rock, that had been a nuisance all its life. It had had a habit of going into motel rooms and tearing the furniture, as well as taking possessions. He had shot Ding on 23rd June 1980 and this was confirmed by his wife and a contemporary diary note. A number of people who gave evidence said they had not seen Ding after 23rd June. But in that period, June, July and August, there were seven recorded incidents in which dingoes had harassed children. It was enough for rangers to put up notices in the toilet blocks at the campsite warning tourists not to feed dingoes and seeking permission and ammunition to cull them.

The injunction not to feed dingoes was an attempt to discourage them from coming near people, but there was a dangerous side-effect. Les Harris, president of the Australian Dingo Foundation, an organisation dedicated to upgrading the image of the dingo from that of pest and scavenger and seeking public understanding, was to say that this sudden reduction in a good source created hunger in the dingoes, even more critical at a time they were feeding their puppies. Harold Schultz, of Blenheim via Laidley in Queensland, was to tell Tipple years later that a few weeks before Azaria disappeared, he and his wife had visited Ayers Rock. “We were amazed to see how close the dingoes came to people trying to get food, they appeared to be very hungry,” Shultz said. “I warned a tourist who was trying to put her hand on one which made a rush on her trying to bite. I have been in the country all my life, born 67 years ago, and have had a lot to do with our wild life and their habits. The dingoes here would not come near people. You have a job to see them in the bush. That is why most people think a dingo would not take a baby. People who have not been there don’t know the situation at that time at Ayers Rock. The way those dingoes hang around the camping area, that dingo knew the baby was in the tent and took its chances when the tent flap was open to go in.”

On 16th August, the night before Azaria disappeared, Lorraine Beatrice Hunter, a tourist from New South Wales, at Ayers Rock with her family, saw a dingo attack her son, Jason. According to her later sworn evidence, she heard him screaming and saw a dingo standing over him. She charged at the dingo and the dingo had been slow getting away. That same night, Judith West, a tourist from Esperance in Western Australia, saw a dingo pull at the arm of her 12-year old daughter, Catherine, who had cried. Judith had intervened and the dingo had run away. She had also hunted a dingo away when it pulled at clothes on her clothes line. Greg Lowe, a Tasmanian tourist was at the campsite with his wife, Sally, just before Lindy raised the alarm, said he had seen a dingo at the outside of the barbecue area and had told his daughter, Chantelle, not to pat it because it might be dangerous.

Not all these accounts were known at the time Denis Barritt took evidence, but there was enough for him to form a view that the dingo was a prime suspect. He also had evidence from Judith West and her husband Bill that they had heard a dingo growl a few minutes before Lindy raised the alarm. He had evidence before him of dingo prints found outside the tent, and marks on a sand hill indicating that a dingo had been dragging something, which it had put down briefly, apparently to change its grip, and left an imprint on the sand consistent with the fabric of a baby’s jumpsuit. There was plenty of evidence to support a dingo attack, together with the total lack of evidence that anything else could have happened.

Some people were not satisfied and inquired further. There were serious questions as to whether there had been a dingo at all, and if something else had in fact happened. Now, in September 1981, that safeguard, being the finding of a competent coroner, was failing. The entire case that there had been a dingo attack which had cost baby Azaria her life was unravelling.

Stuart Tipple had a difficult path to negotiate. There were many obstacles in his way, the first being the Northern Territory. The Territory was very much the wild frontier of Australia, where everything was from time to time extreme and the resources for coping were limited. The Territory had an interior so dry that a stranded traveler might die of thirst. It had a “Top End” so wet that a stranded traveler might be drowned, or die of hunger. Even those in more temperate regions were affected by the changes of season. There were only two seasons in the Top End: Wet and Dry. In the change of seasons, when the air was pregnant with heat and moisture, there was a greater incidence of domestic violence. The Top End had had the devastating cyclone in 1974. The Territory was Australia’s front line in world conflict. Darwin had been heavily bombed by the Japanese and the area was still wide open to any invader from the north. And there were the crocodiles, box jellyfish and taipans.

The Aboriginal people were more concentrated in the Top End than anywhere else in Australia. Many were closer to the way they had always lived than Aboriginals elsewhere. There was an ugly history of racial confrontation and the deprivation of land and culture had reduced others to the status of demoralized fringe-dwellers. That was reflected in incarceration rates. Some of the more vulgar whites would joke that the best way to solve the Aboriginal problem was to put a whole lot of them into the back of a truck with a flagon of red wine and a dozen machetes, and leave them to it. On one occasion in Alice Springs, someone placed a bottle of alcohol in the grounds of the John Flynn Memorial Church where Aborigines congregated to drink. The alcohol was laced with arsenic and an Aboriginal woman died.

On 20th July 1980, at Ti Tree, 200 kilometres north of Alice Springs, two police officers forced a car containing eight Aborigines to stop, on suspicion that the driver was highly intoxicated. A scuffle developed. One police officer opened fire, killing one of the occupants and seriously wounding another. Five of the surviving Aborigines were then charged with serious offences and one of the police officers went on trial for murder and serious wounding. Media reporting of the incident so angered local police that an ABC reporter, Terry Price, complained that he was being tailed wherever he went. Price rang the inspector and said that if the tail on him was not removed, there would be a national story that he was being harassed. The inspector got the message. The police officer who fired the shots was acquitted but because of the emotion that had been aroused, the trial of the five Aborigines was transferred from Alice Springs to Darwin.

The Northern Territory had originally been administered from South Australia and the state continued a close association with the Territory. The Commonwealth assumed responsibility in 1910. The Commonwealth amended the legislation in 1947 to allow the Territory to have its first Legislative Council. The council was replaced in 1974 by an elected Legislative Assembly. Paul Everingham had been a solicitor in Alice Springs and had worked closely with Ian Barker, then practising in the Northern Territory, and Brian Martin, also a lawyer. The three knew each other, had mutual respect and were all to become involved in the Chamberlain case. Everingham had served on the Alice Springs Town Council, won a seat in the new assembly and in 1977 became leader of the National Liberal Party. In July 1978, when the Commonwealth granted the Territory self-government, Everingham became the Chief Minister. A passionate advocate for the Territory, Everingham pushed for many things, including a university. If the Territory were to be regarded as a side issue in national politics, it was not going to be for lack of effort on his part. The Territory was not going to be dictated to on how to run its affairs, conduct its police operations or run its judicial system.

The next obstacle Tipple confronted was what might be called anthropocentric arrogance, the feeling that we are masters of everything around us and that animals recognise that. The refusal of so many to accept the dingo story can be written down at least in part to this attitude. Far beyond the rest of the animal world in intellectual capacity, humans have always tended to regard themselves as not only above their fellow species, but in command of them. There is even a biblical injunction, in Genesis 1, verse 28: “And God said to them, ‘be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth’.” They were at his beck and call of Man, or otherwise allowed to follow their own lives, unless those lives and activities brought them into conflict with Man, who would then hunt them away or kill them. The Thylacine came into conflict in Van Diemen’s Land, so it was eliminated. Children were brought up to regard all animals and their interests as subordinate to the interests of Man. Who has not seen a tiny child presume to exert authority over a dog which outweighs it and could, if so inclined, kill the child?

There is sometimes a shock when the seemingly docile animal retaliates. Often it is because of a basic misunderstanding or disregard of the psychology of the animal. A good-hearted person thinks it inappropriate for the dog to eat something it has in its jaws and tries to remove the item, then gets bitten. A mother living in Mt Colah, north of Sydney, was to write to Tipple: “When ordinary domestic dogs, jealous household pets, savage or kill babies, as has happened often enough in Australia – why be so disbelieving when a wild dingo does the same?”

This anthropocentricity has extended to dealing with animals far bigger and more dangerous. We see in the film, Jurassic Park, how actor Wayne Knight’s character got lost on a rainy night, encountered a dinosaur and tried to sweet-talk it: “No food on me!” Of course, from the dinosaur’s point of view, he was food. A tourist in Yellowstone National Park in the United States fed a grizzly bear and, deciding the bear had had enough, withdrew the food and said: “Sorry, feller, that’s enough!” The bear thought otherwise and the man was seriously injured. At an Australian circus, a handler gave an elephant a treat and had more of it in her hand but decided to keep it till later. The elephant reached out with its trunk to get it and the handler moved it away. After a few unsuccessful attempts, the elephant drew its trunk back and with a mighty jerk of the head and trunk knocked over and killed the handler – “removing the obstacle”, an animal psychologist said – and thereby solving the problem. When it came to the case of a dingo allegedly snatching a tiny baby from its crib in the central Australian desert, hearing and smelling a tiny mammal in a vulnerable position, the reaction of so many Australians was: “Oh no, a dingo would not do that!”

This disinclination to accept the dingo story was the background upon which the reinvestigation was mounted. Initially it was led by the evidence of a forensic odontologist, Dr Kenneth Ayelsbury Brown. He told Denis Barritt that he did not think the damage to the baby’s clothing was caused by canine dentition and was more likely caused by deliberate cutting. Brown’s evidence had been rejected by Barritt on the grounds that Brown did not have experience of bite marks through clothing. Brown denied that he felt humiliated by Barritt’s finding and wanted to pursue the investigation because of that. However, he did take the jumpsuit, with the permission of the Northern Territory police, to the eminent British forensic pathologist Professor James Malcolm Cameron, of the London Hospital Medical College. To be fair to Brown, there might have been some disdain at the coroner’s remarks but he was a professional dissatisfied that a problem had not been solved and he resolved to pursue it. Cameron, after an examination of the jumpsuit and examining the patterns of bleeding, ruled out a dingo attack, opting instead to advance a theory of murder. So in through that portal marched a legion of forensic scientists.

Forensic science was the third great obstacle in Tipple’s way, though it should not have been. At least from the days of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s fictional detective, it had become the essential tool of criminal investigation. People could lie and dissemble but traces left behind at the scene of the crime, or carried from that scene, could not be denied. So many crimes had been solved using that science. A tiny spot of blood the killer had not cleaned from the murder scene, a hair follicle that should not have been there, a footprint, a trace of paint, all could point to the offender. The Locard Principle had it that when any two objects collided, microscopic particles would be transferred from one to the other. It became much harder for a criminal, even if he or she ensured there were no witnesses, to be confident that no physical traces remained that could link that person to the crime.

Forensic science could also be used to prove the negative. It was not the suspect’s blood at the scene. It was not the suspect’s fingerprints. The footprints did not match the suspect’s shoe size. If an innocent person is accused, then forensic science should be relied on to prove that innocence. That, accordingly, was the third safeguard. The problem was that this safeguard could fail under the impact of flawed science or incompetent or biased practitioners. Forensic science was not infallible, and when scientific evidence was the mainstay of a prosecution, in the absence of convincing primary evidence, there was danger.

In practice, in almost all successful prosecutions, the scientific evidence backed up primary evidence. When heart transplant pioneer Victor Chang, was shot dead in 1991 during an abduction attempt, one of the would-be abductors had helped police considerably by dropping his wallet at the scene. Other inquiries pieced together the story, but what sealed it was the transfer of paint between Chang’s Mercedes and the offenders’ vehicle, which the offenders had used to stage a minor accident to get Chang to stop. When Sef Gonzales, a student, murdered his family in Sydney in 2001 and painted “Fuck Off Asians KKK” in blue paint on a wall of the house, to turn suspicion elsewhere, a faint smear of blue paint was deposited on his jumper. There was other evidence to convict him. The blue paint was just another piece, to wit strong evidence. Scientific evidence can play a vital role when police have a great deal of evidence but just cannot get the piece that seals it. In Crows Nest on Sydney’s north shore in 1983, John Robert Adams gave a lift to an intoxicated Mary Louise Wallace. His story was that they had had sex in the car, he had then gone to sleep and when he woke, she was gone. She was never seen again. Adams maintained his innocence for decades, but in 2013, police founds strands of hair in the boot of his car which could be linked to Mary Wallace. That confirmed what police had always thought, that he had killed her and put her body in the boot of his car. The hairs had remained even though it was on record that Adams had been seen carefully cleaning his car soon after Wallace disappeared. Adams was charged with murder and in 2017 he was convicted.

Popular television series, such as Crime Scene Investigation focus on the seeming infallibility of forensic science. Television’s Detective Columbo burrowing away at what has been left behind seems to always get his man. Such has been the enthusiasm for forensic science that juries have sometimes been inclined to overlook deficiencies in primary evidence, questions of motive and whatever else, and rely on the what they see as cold, hard facts, or supposed facts, coming from scientific observation. In the London Hospital Medical College, Professor James Cameron told his students the forensic laboratory was the “Temple of Truth”. Tipple said later: “The way I see it is that people are quite willing to accept that other people make mistakes. However, they see every bit of scientific evidenced as infallible. It is a big problem. What people don’t realise is that even fingerprint evidence is subjective.”

Occasions when convictions obtained largely on scientific evidence had left people unsettled and there were convictions that had been, or were to be, overturned because of changing views on the scientific evidence. On 15th September 1964, a hotel waiter, Alexander McLeod-Lindsay, returned home in Sylvania, in southern Sydney, in the early hours to find his wife, Pamela, and son, Bruce, had been savagely assaulted by someone wielding a jack pick. McLeod was charged with attempted murder because the pattern of blood spatter on the wall of his bedroom apparently matched blood spatter on his jacket. McLeod-Lindsay said the blood had got there when he picked his wife up. He was convicted, though there was no evidence of motive, and the sighting of him that night by work colleagues, together with his seemingly untroubled demeanor at work, suggested he was totally innocent. McLeod-Lindsay was sentenced to 18 years gaol for attempted murder. There were protests about the conviction but McLeod-Lindsay failed in his appeals. He was released on parole in 1973 and set out to rebuild his life as best he could.

In Adelaide, a spray-painter, Edward Charles Splatt, was convicted of the murder of Rosa Amelia Simper, 77, killed violently in her home in the early hours of 3rd December 1977, because trace elements such as paint, metal and timber fragments found at the home matched trace elements found at Splatt’s home and on his clothes. The case had some worrying problems. There was no primary evidence, no apparent motive, no evidence that Splatt even knew Rosa Simper, and no evidence that he had tendency towards violent homicide. The police, at the start of their investigation, had only the trace elements to work on. They decided that the obvious source of the paint and metal fragments was a structural steel manufacturing factory, W.E. Wilson and Sons, Pty Ltd, diagonally opposite Simper’s house. In their investigation of W.E. Wilson employees, police singled out men who worked at the factory, did a forensic search of their homes and settled on Splatt, where it was alleged there were so many trace elements matching those in Simper home it had to be Splatt. On 24th September 1978, Splatt was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. His appeals failed and police said proudly that it was “all done on forensics”. One of the forensic investigators, was Sergeant 1st Class Barry Cocks, of the South Australian Police Technical Services Division, was to become involved in the Chamberlain case. But as at September 1981, there was a challenge to Splatt’s conviction, led by an Adelaide Advertiser journalist, Stewart Cockburn, whose articles the previous May had annoyed officialdom and prompted a review of the case, led by the very man who had been the prosecutor, and together with a colleague from the SA Law Society, had rejected the need for a review. However, that was not going to be the end of the matter.

James Malcolm Cameron, on whose opinion the entire Chamberlain inquiry would reopen, was a graduate of Glasgow University. He had joined the London Hospital Medical College in 1963. Cameron was described as having an “extraordinary insight into casework” and a “low threshold of suspicion when confronted with sudden death”. He was unafraid to speak his mind. In the 1960s and 1970s he took those qualities into what had been regarded as “taboo” areas of forensic medicine, child abuse. He was co-author of a paper on battered children in 1975, Guide to Baby Battering, which had been circulated to hospital staff, instructing them how to recognise signs of baby battering. It became a standard text. When it came to offences against children, naturally the community was outraged, even the prison community who would usually exact their own revenge, and the forensic scientist who exposed the perpetrator tended to be a hero.

Cameron had developed forensic techniques which had brought him fame because of his ability to crack cases that might have escaped traditional investigative work. In 1977, he had worked on the case of a murder victim whose head and hands had been removed. Working on what was left, he identified the victim through the curvature of the spine, and as a result, two men were convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. In the late 1970s, according to author Colin Evans in his book, A Question of Evidence, the British Society for the Turin Shroud invited Cameron to examine the shroud. In his report, Cameron said: “The image of the face is of one who has suffered death by crucifixion.” He found “deep bruising of the shoulder blades, indicating the angle at which the beam of the Cross might have been carried” and the scourge marks on the body would be “consistent with the flagrum, a short-handed Roman whip with pellets of lead or bone attached to its thongs …The image indicates to me that its owner – whoever it might have been – died on the cross, and was in a state of rigor when placed in it”. Cameron did pull back from saying that this was definitely evidence that it had been the shroud of Christ. How was it possible that so much could be read into stains on a piece of cloth which was at least centuries old, if not millennia? One theory was that the Turin Shroud was a medieval forgery, in which the vague Christ-like image had been painted. But he was proud of his interpretation of the Shroud. Was Cameron even then showing a tendency to go well beyond the bounds of what he could reasonably deduce?

Serious problems relating to forensic science had arisen in Britain when forensic science gurus were shown to be all too fallible. Sir Bernard Spilsbury (1877 – 1947) had been a profoundly influential British forensic scientist. His authority filled the courtroom. Regarded as a virtuoso in the witness box, he was skilled in persuading juries of his viewpoint. Knighted in early 1923, he had been approved by the Home Office and had lectured in pathology at the London Hospital Medical College, which was to become the base for James Cameron. However, he became dogmatic and inflexible, conveying the impression that he was infallible, and causing concern within the judiciary. Doubts were being expressed publicly by 1925, and later these doubts were emphasized and the opinion was expressed in some of the major cases in which he was involved that his unwillingness to engage in academic research or peer review, might mean there was sufficient doubt as to produce an acquittal. His domination of the courtroom threw doubts on the jury system.

Further material was to come to light that Cameron himself had had a significant failure. In October 1975, the Appeal Court in Britain quashed the convictions of a youth and two boys for the murder of a homosexual prostitute, Maxwell Confait. Confait’s body had been found after a fire in a house in Catford, in south-east London, in April 1972. The three were gaoled, the youth for life, one of the boys for four years and the other detained under the Mental Health Act. But it became clear in later inquiries there were large discrepancies in the evidence that convicted them. The three had allegedly confessed to the crime, never a good look for someone claiming to have been wrongly convicted. In the light of the facts that became known, it did not appear possible for them to have carried out the killings at the time alleged. Cameron, it turned out, had not taken a rectal temperature which would have put Confait’s death two days earlier than stated. It also transpired that Cameron had failed to notice discolouration of the abdomen, which should have indicated to him that the victim had been dead for some days. There was a degree of rigor mortis at the time Cameron examined the body. He had said the fire had sped up the onset of rigor mortis. But in fact, there had been rigor mortis for some time, and it was just starting to wear off.

At the very time of the renewed investigation into the disappearance of Azaria, attention had been focused in Britain on the case of one John Preece, convicted in 1973 of rape and murder of an Aberdeen housewife, Helen Will. Evidence against Preece had been given by a forensic pathologist, Dr Alan Clift. Preece had examined blood and semen, hair and fibres. There was no evidence that Preece had ever met the victim. But science, it was thought, had the answer. Clift had analysed a semen stain on Helen Will’s underwear and concluded that the killer had been a blood group A secretor. A secretor was someone who secretes detectable levels of their blood in their bodily fluids such as saliva and semen, which allows their blood group to be analysed from such stains. But what Dr Clift did not mention was that the victim had the same blood group, and with that to work on – DNA technology then being in the future – it was not possible to say that the blood, and for that matter the semen, came from Preece. When this came out at Preece’s appeal in March 1981, Preece, who had spent eight years in gaol, was exonerated and Clift condemned. Three hundred and thirty cases where his evidence had sent people to gaol were then reviewed and Clift hustled off into early retirement.

Cameron’s report, in which he advanced a theory that Azaria had been murdered, would turn out to be another in this stream of disastrous forensic investigations. It destroyed the safeguard of the coroner’s finding and had it held would have stopped the looming disaster in its tracks. For the Chamberlains, some of the pieces that would condemn them were locking into place. But there were still safeguards to go.

The announcement of the reinvestigation of the baby’s death unlocked the feelings of the mob. When the reinvestigation of Azaria’s death was announced, many Australians were already skeptical about the dingo story. Some were not ready to give them any benefit of the doubt. There was belligerence provoked to a large extent by perceptions of the Chamberlains and their religious faith. There were those who, seeing a couple at a disadvantage, were ready to leap upon them. This might be called the “yobbo mentality”, which is a worldwide phenomenon, the outlook of loutish, uncultivated people, who sneer at and ridicule things beyond their comprehension. They join in a mob mentality and seek out a publicly available target. This is present in varying degrees in many people. It can be seen in any school yard in the country, where a pupil who is a little “different”, and uncompetitive, is singled out for abuse and bullying. It can be seen in attitudes towards migrants. The Seventh-day Adventist Church was not widely understood. There was a widespread feeling that it was just a cult and it was often confused with Jehovah‘s Witnesses. “There was survey done about attitudes towards religion,” Tipple said. “I was shocked to find that some people thought Adventists wore special underpants.” More ominous suggestions had it that the SDAs practised black magic, even child sacrifice. None of that was true, but it was difficult to dispel.

When Lindy Chamberlain cried out in the central Australian desert on 17th December 1980, that “a dingo’s got my baby”, then appeared on television with Michael seeming strange and distant, even cold, that was enough to set tongues wagging. Their faith was not readily understood, nothing about them, not even the name they had chosen for their daughter, added up. Denis Barritt was aware of that, and took pains to telecast his finding, itself unprecedented, in order to quell such rumour and innuendo forever. The televised finding had the opposite effect. It appears to have humiliated the NT Police, the NT Government, individuals such as Kenneth Brown, and the Northern Territory as a whole. It appears to have filled the NT Government and police, northern Territory Government and police with a determination to continue the investigation. When the renewed inquiry was publicly announced, the mob applauded.

When Stuart Tipple, a New Zealand boy who had settled to life as a provincial Australian solicitor, took this case on, he looked immediately, as any lawyer would, to the safeguards still in place. The police reinvestigating the case might have found the original explanation was correct after all. Or they could have found insufficient evidence of foul play. The forensic scientists engaged by the Crown similarly might not have come up with seemingly incriminating evidence. If there were to be another inquest, the view the new coroner might take was potentially another safeguard. There were many safeguards still ahead, including a possible jury and appeals courts. If the Chamberlains were innocent – and Tipple was sure they were – then that had to come out somewhere along the line. Tipple was entitled to have some confidence and optimism.

Tipple’s experience was relatively limited as might be expected of any young professional only six years out from training. Although hardly a babe in the wilderness, he had no idea that all the safeguards in place ahead of him were going to fail, one by one, and that Lindy was going to be rushed headlong into a life sentence for murder and Michael convicted of a related crime. To unravel this mess was going to take much of his remaining professional life. Where, in the normal course of things, he would have led a successful practice in Gosford New South Wales and enjoyed a peaceful life, he was to be plunged into the national, even international battleground and be forced onto the ropes where he would have to contend, not only with flawed operations which put his clients at such disadvantage but also with sustained attacks on himself from his clients’ supporters for supposedly failing them. Many tears were to be shed, including some of his own.