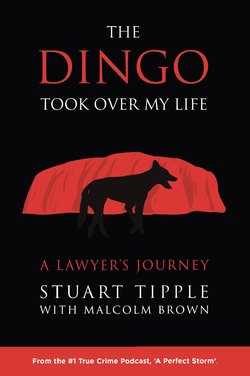

Читать книгу The Dingo Took Over My Life - Stuart Tipple - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two FROM PROVINCIAL NEW ZEALAND

ОглавлениеWhen we are children we seldom think of the future. This innocence leaves us free to enjoy ourselves as few adults can. The day we fret about the future is the day we leave our childhood behind.

― Patrick Rothfuss

Stuart Tipple and Michael and Lindy Chamberlain were all innocents: New Zealand-born, Seventh-day Adventists and churchgoers. They were to encounter each other, and that experience, which would take up the prime of life for all of them and leave them badly affected by a world that had taken away that innocence and left them wounded. Nothing that any of them had ever done had brought upon them what was going to happen. They might each have thought as the crisis deepened, how good it would have been to have returned to their lives in provincial New Zealand and start again. However, the harshness of life was set to descend on them before they ever left New Zealand.

It might be said, if we were to probe a little deeper, that there were other, more subtle, undercurrents in their lives that in some strange way brought them together. Both Stuart Tipple and Michael Chamberlain saw tragic, premature deaths in their families when they were very young, followed by grieving and a search for spiritual rejuvenation. Stuart lost his father through complications from an asthma attack when he was 13 years old, Michael his brother, Geoffrey, though illness when Michael was only seven. Even Lindy, though not having tragedy in her early life, had it in her family history. Her mother, Avis Murchison, was only four years old when her father died and in her early teens when she lost her mother. This obliged Avis to become housemother to two brothers and it might have left her with a strident, authoritarian streak, passed on to Lindy. Both Tipple’s parents belonged to the Seventh-day Adventist (SDA) Church. Michael’s mother, Greta, brought up a Baptist, converted to Seventh-day Adventism following family trauma. Michael turned to Adventism because of another traumatic experience.

Lindy’s father, Cliff Murchison, was an SDA pastor. The church was established in Australia in January 1886, when 29 members met in Melbourne. It was established in New Zealand in October 1887 at Ponsonby, an inner suburb of Auckland. That year, Ellen White, an SDA pioneer from America, co-founded Avondale College, Cooranbong, as the “Avondale School for Christian Workers”. Cooranbong, in the Lake Macquarie hinterland, was on flat, rather marshy countryside, idyllic in some ways but rather isolated, perhaps a good place for a spiritual retreat and contemplation but hardly outward-looking, though the trainees were to go out into the world. The college’s primary purpose was to train missionaries and school teachers to move out into other parts of Australia, New Zealand the South Pacific rim and sow the seeds of its education and health message in the context of “apocalypse now”.

The SDA church, a New World church coming so lately onto the scene in Australia and New Zealand, after Old World Christian churches had established themselves, made headway as a revivalist movement. The SDAs preached the imminent Second Coming and the need for Humanity to be prepared for it. They were to live good lives, abstain from alcohol, preferably practise vegetarianism, observe the moral principles of their Christian faith, keep physically fit and turn themselves out neatly. The SDA Church stuck to the letter of the biblical text by observing the Saturday Sabbath, a point where the mainstream churches differed, saying the SDAs were taking the Fourth Commandment about observing the Sabbath to an extreme and it did not matter when the Sabbath fell.

Stuart Graeme Holden Tipple was born at Blenheim, on New Zealand’s South Island, in 1952, a third-generation New Zealander. His grandfather, John Tipple, an Anglican, had fought with the British Army in the Battle of the Somme, showing great proficiency as a sniper. In 1924, John migrated from Suffolk to New Zealand and took up employment as a builder. John Tipple’s wife died when his son, Frank, was very small. John brought up his two children by himself. Hearing about a new principal, sporting a Master’s degree, coming to the local SDA school at Papanui in suburban Christchurch, he sent Frank there. Frank finished his schooling and then went to Longburn College, an SDA establishment at Palmerston North on New Zealand’s North Island. At this time, Frank decided to become a Seventh-day Adventist. He met his wife-to-be, Margaret Gardener, a Seventh-day Adventist and a direct descendant of the great Scottish Reformation theologian, John Knox. The couple fell in love and they were married in Wellington. A son, John, was born in 1948, followed by Stuart in 1952, David in 1955, Trudi in 1958 and Barbara in 1964.

The Tipple family moved to Christchurch where Frank, not confident that the building trade he was engaged in could give him a steady income, decided to study for a Master’s degree in Education. The years Frank spent studying were difficult for the family because everyone had to be quiet at night while Frank studied. Frank graduated in 1961, joined the Education Department and was posted to Fairlie in rural New Zealand, near Lake Tekapo, looking out on New Zealand’s Southern Alps. Being the only Seventh-day Adventist family in town, the Tipples were looked at a little askance, but the family came to love the Fairlie community and because the family lived on a rural property, Stuart took quickly to the outdoor life. He also took a fancy to table tennis. The family didn’t have a table tennis table so his father set Stuart up a small table the father had used to help with his wallpapering. Because the table was small, Stuart had to acquire faster reflexes, and that enabled him to win the Fairlie junior table tennis championship.

After two years, Frank Tipple was transferred back to Christchurch, where the family settled in the suburb of Papanui. The fifth child, Barbara, was born in 1964. Frank became Geography master at Avonside Girls’ High. Stuart went to the Papanui SDA Church where, at the age of 11, he met Peter Chamberlain, younger brother of Michael, who was about the same age, and they struck up a friendship. Stuart was invited to the Chamberlains’ farm where Stuart met 21-year-old Michael. Stuart saw that Michael, a very presentable young man, was doted on and pampered by his mother. Stuart and Peter began hunting ducks, rabbits, hares and deer.

Michael Leigh Chamberlain was born in Christchurch, on the South Island of New Zealand, on 27th February 1944. His great-grandfather, William Chamberlain, had built one of the local Methodist churches and had, reportedly, raised a militia in New Zealand to send people to fight in the Boer War. Michael’s father, Ivan Chamberlain, was a warrant officer at the time, serving as a pilot instructor in the Royal New Zealand Air Force. Ivan married Greta and after the war took to farming and served as a Methodist Church trustee. Michael, their first-born, was given the middle name “Leigh” probably in memory of Samuel Leigh, the great Methodist missionary.

Michael was brought up an 81-hectare farm on the Canterbury Plains outside Christchurch. He had ill health as a child, surviving a bout of tuberculosis. He had a younger brother, Geoffrey, born with spina bifida, who died in 1951. Michael was to write: “I was too young to understand. I just saw the tragic consequences of my mother Greta’s spiritual struggle to keep Geoffrey alive. She was searching for an answer: What’s wrong with us? Why is this happening? Why is an innocent struck down? (These were questions I too had cause to answer later in life). My mother was a very religious Baptist woman. In her quest for hope, mother attended all sorts of spiritual experiences, some weren’t Christian. My father didn’t want to know about my mother’s spiritual search. I don’t think he knew how to deal with it. It was too painful. My mother even went inadvertently to a spiritualist who used charms, pendants and pendulums, hoping they could somehow save Geoffrey.”

Peter Chamberlain was born in 1952, and life resumed. Even that – a child born replacing one who had died – was to be repeated in Michael’s life. In the meantime, Michael went to Lincoln High School in Christchurch, where he became a prefect and represented the school in athletics, Rugby Union, tennis and cricket and was the captain of the 1st X1. Michael finished his schooling at Christchurch Boys’ High School and in 1963, he enrolled at Canterbury University in a Science degree, thinking he might become an industrial chemist.

Greta Chamberlain in her quest for spiritual fulfilment settled on Seventh-day Adventism and took Michael and Peter with her to the SDA church. In 1963, Michael suffered a serious motorcycle accident. He was counselled by an SDA pastor. During his convalescence, he thought about the serious issues in life and as a result decided to convert from Methodism to Seventh-day Adventism. He completed a second year of his Science degree in 1964 and then in 1965, at the age of 21, elected to become an SDA pastor and to travel to Australia and study theology at Avondale College.

At the time Michael Chamberlain embraced Adventism, the SDA church was changing. As author Lowell Tarling was to observe, the church was then seven or eight generations old and was “growing up”. It had dropped its sectarian characteristics and was becoming a proper denomination. Michael Chamberlain was to point out in his book, Beyond Azaria, Black Light/White Light, that in the mid-1950s two American protestant theologians had concluded that the SDA Church was not a cult at all. The problem was – and this was to come out later – the Seventh-day Adventists were still regarded as separate and to some extent exclusive; they were right, others were wrong, they would achieve salvation, others would not.

The problem facing Adventists was further compounded by the fact that they tended to stay with their own kind. Tipple said: “Most Adventists live their lives in a bubble. They are born SDAs, they go to SDA schools and many of them end up working for the SDA church. The thing about Catholics is they are encouraged to go down to the pub and have a few beers.” But that was the life Michael Chamberlain had decided for himself. He went into it with his eyes open.

Stuart Tipple and his brothers helped Frank in his building work which he undertook during school holidays. Frank converted a property into flats and had half-completed the renovations of the family home when in December 1965 he died suddenly. Margaret, with five children, including a baby, was hard-pressed. Stuart remembers how the local SDA community moved in and began a project to finish the renovations of the family home. With Frank’s life insurance payout and income from leasing of the flats, the family was able to get by. And in the long, hard road ahead of her, Margaret became more spiritual. “She told me that when Dad died, she made a covenant with God,” Stuart said. “She asked God to become father of her fatherless children.” Stuart for his own part made a decision that he would “never ask Mother for a dollar”. He earned his own pocket money by delivering groceries by bicycle.

Stuart Tipple and Peter Chamberlain continued to get on well. Peter said: “We could talk freely with each other and often with different points of view. Yes, we argued but never in anger. We soon became great mates. Stuart was an honest clean-mouthed friend, and was there to back you up when needed in argument or fight. We were baptized into the Adventist Church at the same ceremony.” Stuart was without a male mentor or role model, so he learned to be self-sufficient, though Margaret kept the family on an even keel. Peter said: “Margaret enjoyed finding out what you thought, or how you ticked. She never would harp on your bad points, but would soon give her shilling’s worth if you questioned her better judgement. I respected Margaret, a special person and having to bring those Tipple boys and girls up single-handedly and with a baby in arms still. I admired her guts.

“It wasn't easy for the family to lose a dad so young or suddenly. My mother Greta was more of a follower, while Margaret was her own person, and I feel this helped this family to seek out the vocation they preferred in life. One of Stuart’s better points in life, was he waited and listened before he spoke. I was the opposite. I knew I was no saint like Stuart. He was a great mate in my early youth and probably helped me stay on the straight-and-narrow more than I helped him. Yes, we enjoyed duck hunting on the farm, social rugby and a little deer recovery to make a bob or two. We met some outdoor hardships together but were able to laugh about them later.”

Stuart Tipple finished his schooling at Shirley Boys High School but felt no inclination to do Law. He believed that a prerequisite for Law was Latin and because he had not studied Latin, he did not consider it as a possibility. Awarded a bursary to do teacher-training, he decided to follow his father into Education. When he went to enrol at Canterbury University in Christchurch, he discovered that Latin was no longer a prerequisite. He enrolled in Law. It meant he lost his bursary and to get himself through, he realised he would have to work part-time. His first job was cleaning windows. He made extra money shooting with Peter and selling deer carcasses to butchers. Then he did a tradesman’s course and worked as a drain-layer’s labourer, installing stormwater and sewerage pipes. “He worked hard for his extra dosh,” Peter said. “Often, I'd see him come home covered in dirt from drain laying for Stan Brown, our social Rugby coach.”

At Avondale College, Michael Chamberlain, having a better time of it, living a clean, healthy life and studying theology, became friendly with another theology student, Phil Ward. “I quite respected Phil – he was a highly creative preacher,” Michael said in Beyond Azaria. His sermons were completely different, out of left field.”

On 4th March 1948, Alice Lynne “Lindy” Murchison was born in Whakatane, on the North Island of New Zealand, daughter of an SDA pastor, Cliff Murchison, and Avis. Lindy’s paternal origins were in the Isle of Skye off Scotland. Her great grandfather, Malcolm Murchison, arrived in Australia in 1852 with wife Flora and an infant son, Alister, and settled in Geelong, Victoria. Flora ran the toll booth gate in Geelong. Alister died very young but their next child, Alexander Murchison, took to the land and set up sawmills and creameries in Victoria. He married Isadora Kate Marr, of Irish convict stock who was the proprietor of the Post Office Tea Rooms and Accommodation in Hobart. The couple settled in the Otway Ranges where Alexander started pioneer farming. Alexander was heavily involved in the Victorian Conservation Commission.

The Murchisons had a son, Clifford, or Cliff. They lived next door to another Cliff, Cliff Young, who became his friend and would become known throughout Australia for his long distance running in gum boots. When Cliff Murchison was very young, he accepted Christianity and decided to become a Seventh-day Adventist, the first in his family to do so. He also decided, in his teens, to become an SDA pastor. He left home and worked in rural Victoria selling books door-to-door to raise the money to go to Avondale College. He worked in Melbourne for a short time. Cliff was at Avondale College from 1933 till 1938. He worked in the college dairy during the terms and eventually got permission to start a local milk round, on foot, with the excess milk that had formerly been thrown away. His enterprise was so successful that the college bought a horse and cart to expand the service.

In 1939, Cliff Murchison was posted as an SDA pastor to Christchurch in the South Island of New Zealand. He met Avis Hann, a New Zealand-born girl with English-German-Spanish heritage, who came from Stratford on New Zealand’s North Island. They married on 15th October 1941. A son, Alexander, was born on 20th August 1942 at Rotorua. Lindy arrived in 1948. She was 20 months old when the family settled in Victoria in 1949. Both Alexander and Lindy were brought up as Seventh-day Adventists. Alexander went to school in Melbourne. “Lindy started school when we were in South Gippsland,” Alex said. “She was a happy, cheerful creature but I found out that when I teased her even at an early age, she would stand up for herself.”

Cliff Murchison continued at various appointments around Victoria. At one of those postings, at Benalla, Lindy went to High school with and subsequently dated Alex Gazik, who went on to Avondale College to study theology. Cliff Murchison’s pastoral travels took him north of the border, to Broken Hill in New South Wales. At Avondale College, Michael shared a room with Alex Gazik, who still dating Lindy Murchison and had put up a large colour photo of her on the wall. Alex consistently “promoted” Lindy to Michael as someone he should meet. Michael said: “I gave in, accepting his word on a fateful hitch-hiking race to Broken Hill.” Soon afterwards Lindy and Alex broke up. Michael visited again the next year with Lindy’s cousin. Everything else followed. “Lindy and I fell in love, and I courted her by letter,” Michael said. “We spent 19 full days together before we got married, such was the insulation of college life.” Michael graduated in 1969 and married Lindy at the SDA church in Wahroonga on Sydney’s North Shore. Michael was posted to Tasmania, where he was very active in the community and wrote radio scripts. A son, Aidan, was born in 1973. Michael was ordained as a pastor just before they were transferred to North Queensland around Christmas 1974.

Phil Ward graduated in Theology and showed aptitude during his college years. He did not become a pastor but instead began work as a TV news camera man and started a publication, Small Business Letter, which was successful. He used his skill as a camera man by taking a film of Michael and Lindy’s wedding which he edited and gave to them as a wedding gift. It is necessary to mention Phil here because he was to loom much larger in the lives of Michael and Lindy at a later time.

Stuart Tipple graduated in Law in New Zealand in 1975. Setting out to work there presented difficulties. The country was, in Tipple’s words, “in a pretty bad way”. “I think about 40 of us graduated but there were only two positions available for articled clerks,” he said. “I managed to get one of them.” Tipple was accepted by the firm, Harper Pascoe and Company, in Christchurch, unusual in that he was “an Adventist boy when everyone else in the firm had been to Christ’s College”. Stuart pointed out to a senior partner that he was the only lawyer the firm had ever employed who had not been to Christ’s College. The partner thought long and hard before replying: “That is not right. In 1942, we employed someone who had been to St Andrew’s, the Presbyterian College.”

That same year, Michael, with Lindy and Aidan in tow, was posted to North Queensland as an SDA pastor. Reagan was born in Bowen on 16th April 1976. From 1977, Chamberlain ran a radio program, called The Good Life, on two radio stations in North Queensland. He also wrote columns for the Cairns Post, and he took no pay for his columns.

Tipple was admitted as a solicitor of the Supreme Court of New Zealand in 1976. But by then he was looking further afield. He decided to go to Australia because his girlfriend had gone there. He arrived in Sydney in February 1976 and found employment as an administrative assistant at the Sydney University Law School. He also lectured part-time in Law at an institute for the Commonwealth Department of Foreign Affairs. From there, he joined the NSW Public Solicitors’ Office, in Bent Street, Sydney, and was assigned to the Indictable Section, dealing with serious crime, such as murder, manslaughter, robbery, rapes and serious assault.

Tipple was learning the criminal law from the bottom up. Being a Public Solicitor made him a “poor relation” in the legal establishment, but the work was far from boring. He went to Katingal, the maximum-security prison at Long Bay Gaol, to consult with Russell “Mad Dog” Cox. A week after Tipple took instructions from him, Cox thought a more expedient way than waiting for a court appearance was to escape. His escape from Katingal was one of the more famous of the state’s gaol breaks. “In Katingal, they would let you out for exercise so many hours a day,” Tipple said. “The only area not under surveillance was behind the door that opened out into the exercise yard. It was a cage. He had obtained a hacksaw blade and every time he went through the door, he jumped up and sawed at a bar. On the day he escaped, he cut right through the bar, got up and out. They shot at him.” The matter was mentioned in court the following week and Tipple remembers telling the judge, Justice Yeldham: “I was having difficulty getting instructions.”

Tipple also took instructions from James Edward “Jockey” Smith, who was a notorious bank robber and prison escapee, who was alleged to have shot at and tried to murder police officers. Smith had complained loud and hard about what he claimed was police corruption. “This case of Jockey Smith was a watershed moment for me,” Tipple said. “He was not a violent criminal, before he was labelled Public Enemy No 1. When I went to see him in Parramatta Gaol, I thought I was about to see this big, tough criminal. Instead I met this small man who sobbed about police corruption and how he had been fitted up.” According to Tipple, Smith claimed the police had said, ‘We will get you, you little bastard’.” When Tipple got into Smith’s case, he realised that the case against him was “full of holes”. “Smith had been identified by a police officer in court but he had failed to identify him from wanted posters in his police station,” Tipple said. “I saw this was dodgy. This identification evidence should not have been admitted.” When Tipple tried to speak to the Senior Public Defender, Howard Purnell, about it, Purnell was still inclined to write him off as Public Enemy No 1. This was a significant moment in Tipple’s development as a lawyer. Sure, the criminals are cunning and deceptive, and to meet that the police have to develop cunning themselves. There is a tendency for them, and the prosecutors, to stray beyond the bounds of professional objectivity.

There comes a point where the prospect of conviction/acquittal becomes a contest between individuals. Years later, Lindy Chamberlain would tell Tipple a police officer had told her: “We’ll get you, if not this time, we’ll get you next time.”

Tipple persisted in his advocacy for Smith. Whatever Tipple might have thought of him privately, Smith had rights. “You have to look at this case!” Tipple told him. Tipple persuaded Purnell there was merit in what he had to say. Purnell took up the case and Smith was acquitted, and it was another lesson for Tipple. “We had a wonderful win,” Tipple said. “Smith’s convictions for the shooting of a police officer, Jeremiah Ambrose, and the murder of bookmaker Lloyd Tidmarsh, were overturned. I realised then that no matter how skilled and experienced your barrister is, even a junior solicitor can have influence.”

In his work with Purnell, Tipple was appearing in the High Court and the Court of Criminal Appeal two days a week. In one case, he worked with the then Public Defender, Michael Adams, with whom he was to have later acquaintance. Tipple became involved in a case where an osteopath, Petronius-Kuff, had gone with a friend to Ron Hodgson Motors and produced a cheque as payment for a Jaguar car they drove off in. Kuff asked the dealer to hold the cheque because the money was still coming through. They later gave the dealer another cheque, which bounced. Kuff was charged with obtaining property through false pretences. Adams and Tipple argued that under the terms of the contract, Kuff never would never have gained legal ownership of the car until he had paid for it, and because Kuff didn’t pay for it, he was not guilty. The court decided obtaining possession of the car was enough and Kuff was convicted. “If they are against you, they are against you,” Tipple said later. “If a court decides your client is the bad guy and undeserving, it’s very difficult to win, no matter how good your legal arguments are.”

During his two years with the Public Solicitor’s Office, Tipple visited his sister, Trudi, who was working at the Sydney Adventist Hospital, “The San”, in Wahroonga. During one of those visits, he chanced upon another nurse “a beautiful girl”, Cherie Kersting, whom he asked out. One night, about to go to a law lecture, Tipple suggested Cherie should look for an engagement ring. “She had found one by the time I got out of my law lecture,” he said. After they were engaged Cherie graduated from her nursing course and moved to Melbourne to live with her parents. She began modelling and her agency urged her to enter the Miss World competition. Cherie decided not to because it would have delayed their wedding plans. The agency persuaded another model in their agency to enter and that girl went on to become the Miss World runner up. Stuart and Cherie married at the St John’s Uniting Church at Wahroonga on 5th December 1978.

As a married man, Tipple found the demands on his time exacting. He was constantly in court or going to prisons. His clients were for the main part, as legendary Sydney solicitor Bruce Miles put it, “the hopeless and the helpless”, and the nastiness of what he had to deal with started to wear. “What finished me was having to take instructions from a man who had killed a woman and had not told anyone about it so he could keep getting Social Security benefits,” Tipple said. “I saw these awful crime scene photographs and then had to interview this man, who happened to be suffering from tertiary syphilis. That was not the romantic criminal law that as a young lawyer you like to imagine. I thought there had to be better ways.” When he was on his honeymoon, Tipple saw a position advertised for a solicitor with Hickson Lakeman & Holcombe, a Sydney law firm, and applied for it.

Accepted by the firm, Tipple did general litigation work, acting most of the time for insurance companies. By now he was conscious of financial pressures. House prices in Sydney were rapidly rising and he feared, though he was now getting a professional salary, that he and Cherie might not be able to afford a home. So, where else could he go? Way out in the backblocks of the state? Or somewhere near to Sydney where the prices were lower. He looked to Gosford, where he had recently appreared in court. The Central Coast, which was a developing area and had good prospects, suited him and he bought a home in 1979. A friend sent him an ad by the Gosford law firm, Brennan and Blair, which was seeking a solicitor. He got the job and, as he realised, started at the bottom, “doing all the work nobody else wanted to do”.

The Chamberlains in north Queensland were living a full pastoral life. Michael went jogging every morning, it being the ethos of Seventh-day Adventists to be physically fit. Michael’s other great interest was photography. He carried a camera in a bag beneath his legs as he was driving, so he could whip the camera out at any moment. He was broadcasting and writing a column on health and fitness in the Cairns Post. On 17th June 1979, 15 kilometres south of Port Douglas on the North Queensland coast, Michael and Lindy Chamberlain picked up an accident victim, Keyth Lenehan, bleeding from lacerations to the skull. They put him into the car through the back. According to Lindy, he was lying with his feet in the hatch area of the car, with his shoulders on Lindy’s lap, and his head between the two front passengers’ seats. The blood might have flowed down between the two seats. Michael drove to Cairns Hospital where Lenehan was taken in as a patient. It was obviously a Christian thing to do, and which anyone with a sense of humanity would have done. Lenehan’s blood might well have run down the side of the passenger’s seat and onto the floor, where it would remain as dried flakes.

In January 1980 Michael Chamberlain was posted to Mt Isa in western Queensland to be the SDA pastor. Michael continued his writing on health, religion and community for the Mt Isa Star. Azaria was born on 11th June 1980, the family decided on a holiday to the Northern Territory, including a stopover at Ayers Rock. They took their holiday in August 1980, when temperatures in the Australia inland were cooler, and tragedy struck at Ayers Rock, when Azaria, nine weeks and four days old, was reportedly snatched for the family tent by a dingo. A police investigation followed, then the first coroner’s inquest, which confirmed a dingo had taken the baby. After Stuart Tipple and Michael Chamberlain met on the Wyong street in September 1981, the three individuals – Michael, Lindy and Stuart – all fine, upstanding individuals who had nothing to answer for, came together and would, in essence, be locked together for forever after. Total innocents who had all the vitality and health of a New Zealand upbringing, nurtured in Christian households, they were to spend a major portion of their remaining lives unscrambling a mess they were not responsible for, but which had been created by the muddle, incompetence, bigotry and inflexibility of others.