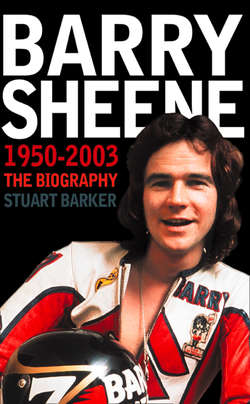

Читать книгу Barry Sheene 1950–2003: The Biography - Stuart Barker - Страница 6

INTRODUCTION

Оглавление‘I’m not going to let fucking cancer get in the way of me enjoying myself.’

It was like nothing had ever changed. The famous Donald Duck logo on the black and gold crash helmet could just be made out as the tall, gangly rider tucked in behind the bike’s screen, reducing wind drag to gain a fraction of a second over his pursuer. The equally famous number seven, crossed through European-style, was emblazoned on the bike’s bodywork as it had been almost 30 years before. It had always been lucky for him. Maybe it could be again.

His 51 years counted for nothing when he was on a motorcycle; it was as much a part of him as the plates, pins and 27 screws that held his legs together. The smooth but aggressive riding style, the determined and sustained attack, could all have belonged to a 20-year-old kid with a fire in his belly and a burning desire to win against the odds. Any odds.

Behind him, the 1987 500cc motorcycle Grand Prix world champion Wayne Gardner tried everything he knew to close the 1.3-second gap. But despite being 10 years younger and having a bike which was 20mph faster than the man out front, there was nothing he could do to get past. The distinctive riding style of the race leader hadn’t changed since he’d started racing bikes in 1968, and his desire to win appeared to be no less now than it was then. It was as if he still had something to prove.

The crowd, as ever, yelled their delight at the on-track bravado of the man in black, urging him on, willing him to make that decisive break, wanting him, needing him to dig deeper to secure a victory. Many of them had been teenagers when they first thrilled to their hero’s titanic battles with the best riders in the world, most of the races televised on ITV’s Saturday-afternoon World of Sport programme – warm, comforting memories of a childhood long gone. There were thousands in attendance who wouldn’t even have had an interest in motorcycles had it not been for the influence of the man who was out there throwing his bike hard over from side to side, skimming his knees off the Tarmac with a grace and style all of his own and gunning his steed down the straights as fast as the laws of physics would allow.

For the vast majority of the crowd, there was only one rider in the race; they would love him, applaud him and later mob him whether he came first or last. But Barry Sheene wasn’t accustomed to coming last. Even after 18 years of retirement from the sport that made him an international superstar, a multi-millionaire and one of the true icons of the seventies, he was out there proving he still had what it took to win races.

The more imaginative among the packed grandstands and trackside enclosures could have transported themselves, mentally if not physically, back to the halcyon days of the seventies when Sheene was on top of the world as the most famous motorcycle racer in history, a pin-up glamour boy for millions of teenage girls and a Boys’ Own hero for an entire generation of lads. Dads and mums alike now took great pleasure in pointing out to their own kids the very man who had quickened their young pulses nearly three decades earlier.

But even the most nostalgic of spectators were forced, however reluctantly, to admit that things were different this time round. For starters, it was 2002, not 1976. And this was not a 500cc Grand Prix World Championship race, it was a classic bike race being staged at the Goodwood Revival event organized by Sheene’s close friend, the Earl of March. Sheene’s bike, a classic sixties Manx Norton, was a far cry from the vicious 130bhp, 170mph monsters he used to tame on race tracks around the world for the pleasure of millions. But the fans didn’t care. It was still Barry Sheene out there, he was still racing a bike, he was still winning, and that was all that mattered.

The most significant change of all, the thing that really brought a lump to the throats of so many and which made Sheene’s eventual victory over Gardner even more remarkable and emotional, was the recently divulged fact that Barry had cancer. This was the first time he had appeared in public since being diagnosed. The poignancy of his win was not lost on the 80,000-strong crowd who realized they were probably witnessing Sheene’s last-ever race.

Barry had been diagnosed with cancer of the oesophagus and upper stomach just a few weeks earlier, and there were more than a few tears shed as he crossed the line, removed his helmet and waved to the masses on his victory lap. He had come a long way to get to Goodwood in the sleepy West Sussex countryside – from the other side of the world, in fact. An 18-hour direct flight from Australia is gruelling enough for most passengers, never mind one suffering from cancer. But to ride flat-out against some supremely talented opposition, including former world champions Gardner and Freddie Spencer, and to eventually take the race win gave all his fans reason to believe that this time cancer had picked the wrong body. Sheene was a fighter and a winner; he had proved it many times before. Surely, if anyone could beat the most dreaded of diseases, it was he.

When news of his illness broke, Sheene shocked fans around the world by announcing he would not be undergoing invasive surgery or chemotherapy to treat his condition. Instead, he would rely on alternative cures and a special frugal diet. Sheene had already lost a stone off his slight frame by the time he appeared at Goodwood, and orthodox oncologists warned that he risked malnutrition by continuing with the diet. But Sheene has always done things his own way, and he was adamant when interviewed by Motor Cycle News: ‘I’m not going to be fighting this in the conventional way. I won’t subject my body to chemotherapy. I’m putting my faith in the natural way.’

Typically for a man who had made a living out of cheating death, Barry put a brave face on his illness and already had his quips and quotes worked out for the media. ‘I don’t like cancer, but it’s growing on me’; ‘If I don’t beat this my wife’s going to kill me.’ These were just two of the lines he bandied about like a stand-up comic living in denial of the very real risk to his life. Sheene also insisted that he wasn’t ‘going to let fucking cancer get in the way of me enjoying myself’ and admitted that his second thought upon hearing his diagnosis was that he might have to miss the Goodwood event. It hadn’t taken long for him to re-establish control, pack a suitcase and catch a flight; he wasn’t about to let down his fans. Anyway, it wasn’t as if fighting for survival was something new to Sheene. In the past he had astounded some of the most respected doctors and surgeons in the world with his ability to recover from serious injuries in unheard-of time spans.

Well-publicized X-rays of his shattered legs from two horrific high-speed crashes played as much a part in making him a household name as any of his victories on the race track. In 1975, his rear tyre blew out at 178mph on the notorious banked section of the Daytona Speedway in Florida. The crash, captured by a television documentary crew who were following Sheene at the time, was shown on TV news programmes around the world, and the incident made Barry famous overnight. His leg was broken so badly it was twisted up behind him, out of sight, making him think he had lost it. He also lost shocking amounts of skin and broke his forearm, wrist, six ribs and a collarbone, as well as suffering compression fractures to several vertebrae. On top of that, damage to his kidneys meant he urinated blood for several weeks. Despite the serious nature of his injuries, Sheene did not lose his 60-a-day passion for strong, unfiltered cigarettes – he preferred the French brand Gauloises, but would happily smoke any brand that was being offered around – and insisted on being wheeled out of the hospital on his bed from time to time so that he could smoke. The hole he drilled in the chin bar of his crash helmet so that he could have a puff on the starting grids at race meetings remains the stuff of legend in bike racing circles, but no one was laughing any more. Sheene’s heavy smoking habit, which had started when he was just nine years old, was one factor cited as a possible cause of his cancer.

The Daytona disaster was the kind of accident that would take ‘normal’ people months, if not years, to recover from. Many would never overcome the psychological scars of remembering every bone-crushing, skin-shredding second of their crash, and would certainly never contemplate getting back on a motorcycle again, but then most people aren’t Barry Sheene. He was racing again just seven weeks later with an 18-inch pin in his left thigh bone, and went on to win his first World Championship the following year.

Crashes are common in bike racing, but big ones like Sheene’s Daytona incident are rare – at least, it’s rare to survive them. Broken arms or legs are frequent injuries, as are abrasions, damaged tendons and general cuts and bruising, but few people live through, or are unfortunate enough to have in the first place, crashes at such extreme speeds. Sheene had not one but two. The second happened seven years and two World Championships later (Barry retained the title in 1977 and was awarded an MBE for doing so) at the Silverstone circuit in England, and it was every bit as bad, if not worse, than the first. Sheene struck a crashed bike which was lying on the circuit just above a blind rise and its fuel tank instantly ignited causing a massive explosion. He had been travelling at around 165mph at the moment of impact. Moments later, another bike hit the wreckage causing another explosion; the resulting carnage resembled the aftermath of a terrorist bombing. Sheene’s already fragile legs had been smashed again, this time more gravely than before, and he also suffered injuries to his head, chest and kidneys.

But while his body was in bad shape, his mental attitude remained as gritty as ever. He told gathered reporters from his hospital bed that ‘Broken bones are a mechanical problem. You can fix them.’ Sheene’s surgeon, Nigel Cobb, inserted plates, pins and a total of 27 screws into his famous patient’s legs and triggered a barrage of schoolboy gags about Barry Sheene and airport metal detectors. But his rate of recovery, once again, was phenomenal.

If Barry Sheene had been a star before his Silverstone crash, he was a superstar after it – and, it appeared, an invincible one. No bike racer before or since has commanded anywhere near the same amount of media coverage as Sheene. It is inconceivable in the current climate of the sport to imagine a national newspaper running a front page story on a bike racer just because he’d met a new blonde girlfriend, and how many other bikers could have starred alongside boxer Henry Cooper in a terrestrial TV advert for a body scent encouraging users to ‘Splash it on all over’? How many racers counted members of the Beatles as close personal friends and dined with Hollywood legends such as Cary Grant? None.

As well as being a world champion racer, Barry Sheene was a marketing phenomenon, gaining exposure for his growing attachment of sponsors in areas even they couldn’t have imagined. He co-hosted ITV’s Just Amazing! show in the eighties and was the star attraction at the 1982 BBC Sports Personality of the Year awards when he rode his new Suzuki onstage and announced he’d be leaving Yamaha to join Suzuki for the following season. He starred as himself in the (very bad) movie Space Riders, and appeared on every major television show of his time from Parkinson to Swap Shop and Jim’ll Fix It to Russell Harty. But perhaps the most enduring legacy of Barry’s fame is that he’s still the only biker the general public as a whole have heard of. Ask any one of them to name a motorcycle racer and they’ll invariably say Barry Sheene. The same thing happens whenever anyone, young or old, is attempting to go too fast or to do something stupid on a two wheeler, be it a motorcycle or a pushbike. The response from policemen and dads alike is always the same: ‘Who do you think you are, son, Barry Sheene?’

Everyone appreciated a British sportsman who was capable of beating the world in an era when such a thing wasn’t (and, sadly, still isn’t) commonplace. Sheene remains the last British rider to win a Grand Prix World Championship despite the fact that he last held the title 25 years ago. Even more than his ability to win, the public applauded his guts and bravery as he came back not once but twice from injuries that would have ended any other sportsman’s career. After his Silverstone crash, Sheene was extremely lucky to be able to walk again, let alone be fit enough to win motorcycle races.

It was this fighting spirit, this never-say-die attitude, which gave hope to millions when Barry announced he was ready to battle cancer and wouldn’t be beaten in the fight. With typical bravado, he commented shortly after being diagnosed that it was ‘a complete pain in the arse’, and vowed to deal with it.

It was a great irony that a man who had spent 16 years risking his life on a motorcycle should retire from the sport still in one piece only to face death from a creeping, silent and devastating opponent from within. The irony was not lost on those who remembered that Britain’s other great champion motorcyclist, Mike Hailwood, was killed in retirement by an errant lorry driver while returning in his car from his local fish and chip shop. Sheene’s former rivals, as well as his constant supporters, were without exception shocked by the news of his cancer, and all of them rallied round to offer words of support and encouragement. Old differences were forgotten. The only thing that mattered was for Sheene to concentrate on beating his disease.

Barry Sheene was the first, and arguably the last, truly mainstream motorcycle racer who could genuinely lay claim to being a household name. In truth, there was no need for him after 1982 to continue to risk life and limb on a 180mph motorcycle when he was already a multi-millionaire with a twelfth-century, 34-bedroom mansion in Surrey, his own helicopter and a guaranteed career outside racing whenever he decided to call it quits. But that’s what made him Barry Sheene: his determination to be the best, to be the fastest, never to give up, to push a 130bhp motorcycle past its limits and bring it back safely again. Sometimes he didn’t bring it back safely; sometimes the bike would savagely bite back and spit Sheene off like an angry rodeo steer ditching its rider. But Sheene always got back on. He always returned to show the bike, and his public, who was boss.

But at the age of just 51, Sheene had a new and even more deadly opponent than a badly behaved, viciously powerful motorcycle, a more lethal foe than speed itself, and a more cunning enemy than any he had faced off before. He had cancer. Without doubt, it would prove to be the toughest battle of his impressive but painful career, but on that day at Goodwood there seemed to be no one in the world with a mindset more suited to combating the biggest killer of modern times. He had cheated death many times before. All he had to do was cheat it one more time.