Читать книгу Barry Sheene 1950–2003: The Biography - Stuart Barker - Страница 8

CHAPTER 2 THE RACER: PART ONE

Оглавление‘He was it. He was the main man who everyone had to beat.’

RON HASLAM

After scoring such a resounding double victory in only his second-ever race meeting, in April 1968 Barry Sheene surprised many people by opting out of racing for a few months. Still unconvinced that racing was the proper career path to follow, he decided to take in a second tour of Europe, this time spannering for a rider called Lewis Young. Young was riding Bultacos, which by now Barry knew inside out, and he wisely came to the conclusion that a season following the Grand Prix circus around Europe would teach him more about the motorcycle racing business than a few weekends spent hurtling round British circuits. It might have seemed at the time an odd move to make, but it proved to be a well-judged one. This time, Barry really laid the foundations for his future career by getting to know all the circuits, the travelling routines and the way of life in the paddock, as well as gaining countless contacts all of whom would play a part in his future. The experience was heady and intoxicating, and by the time he returned to England that autumn not only was he 10kg lighter after eating so sparsely and irregularly, he had also decided to race again. Having seen some of the lesser lights who were competing in the Grands Prix, Barry had become convinced that he could beat most of them.

The year 1969 was Barry Sheene’s first full season of racing, and for the job in hand he had three Bultacos (125, 250 and 350cc), all immaculately prepared by himself and Frank. His Ford Thames van wasn’t quite so immaculate but it was good enough for the job. By the end of it he was being celebrated as the best newcomer of the season, having finished second to and 16 points behind established British rider Chas Mortimer in the 125cc British Championship. ‘I seem to remember that I won the 125 British Championship quite early on that year,’ Mortimer recalled, ‘then I went on to do some Grands Prix while Barry finished off the championship.’

That season very nearly became Sheene’s first and last when his hero and friend Bill Ivy was killed during practice for the East German Grand Prix in July. Sheene was devastated and suffered a massive asthma attack upon hearing the news. He hadn’t had a relapse since leaving school, and he never had another again. He seriously considered packing in the racing game after Bill’s death, but eventually managed to come to terms with the tragedy, as all motorcycle racers must do; it had to be chalked down as an accident and life had to go on. Sheene persisted, and went on to become Bill’s natural successor in the paddocks of the world, the cheeky cockney rebel with a playboy lifestyle and a gift for flamboyancy. Ivy would have been proud of him.

It was his natural flamboyancy that led Sheene to design the most famous crash helmet in motorcycle racing history, and it grabbed lots of attention during the 1969 season. While most other riders wore very basic designs on their helmets, if any at all, Barry had Donald Duck emblazoned on the front of his in a bid to attract attention to himself. It worked, and as the design developed over the years it became the most recognizable in the sport. The completed item featured a black background with gold trimmings, the famous number seven on the sides (more of which later) and, for the first time ever in the sport, the rider’s name on the back. ‘It wasn’t intentional,’ Sheene explained. ‘My helmet had gone away to a chap I knew to be painted and it came back with my name emblazoned on the rear. That’s neat, I thought, and I know I turned many heads when I unveiled it for the first time.’ Over the next few decades it became almost compulsory for riders to have their names on the backs of their helmets, and Barry claimed he was the originator of the fashion.

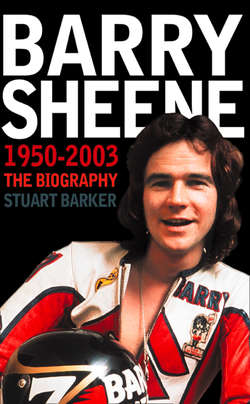

And his fashion sense didn’t stop at helmet designs; he also helped instigate the long-overdue decline in the use of all-black leathers which had so tarnished the image of motorcycle racing. In the twenty-first century motorcycle racing is one of the most colourful sports on the calendar, but it wasn’t always the case, far from it in fact, and Sheene played a large part in the technicolour transformation. In 1972 he ordered a set of white leathers, again largely as a gimmick to get noticed but also as a way of improving the sport’s then drab, greasy image of rough men in black leathers riding noisy, smelly motorbikes. He wasn’t the first rider to brighten up the sport, however, and not everyone was blown away by his garb, as Chas Mortimer testified. ‘I don’t particularly remember Barry’s Donald Duck helmet and white leathers standing out in those days. I mean, I had white leathers then too. Rod Scivyer was the first person to wear them in about 1967 or 1968.’ Sheene would later ditch the white colour scheme believing it was a step too far, but he would go on to wear other brightly coloured leathers such as the famous blue and white Suzuki garments and the even more famous red and black Texaco outfit.

With the trauma of Bill Ivy’s death behind him, Sheene set about preparing for the 1970 season with a team set-up and determination as yet unseen. The icing on the cake was the purchase of an ex-factory 125cc Suzuki from retired rider Stuart Graham. It cost a whopping £2,000, which was an enormous sum at the time and certainly out of Barry’s reach without the help of his dad. Barry used every penny he had to secure the bike – he was still driving a lorry for up to 14 hours a day to raise funds – and borrowed the rest from Frank, though he insisted he paid every penny back.

He made a point of letting everyone know that he repaid his father because he had always been acutely aware of the perception that he was born with a silver spoon in his mouth when it came to racing. After all, he’d had two factory Bultacos for his first outing, a world-class tuner in his dad and, through his father’s connections, advice from some of the best riders in the world. Ron Haslam, who began to challenge Barry’s supremacy on the domestic scene in the mid-seventies, recalled Barry’s machinery advantage. ‘He was it. He was the main man who everyone had to beat. I was helping my brother [Terry Haslam, who was killed racing in 1974] who was beating him sometimes even though he didn’t have all the tackle Sheene had. Sheene had factory bikes from the start so it was such a big thing for my brother to beat him on lesser machinery.’ Ron himself struggled against Barry on ‘lesser machinery’ on many occasions; whenever he came out on top it was always sweetly satisfying. ‘Sheene was like any rider in that he thought he was the best, as I did. You have to think that. He had superior equipment but he was still beatable, and I always believed I could beat him.’

Barry knew that his little ten-speed Suzuki was fast enough to run at World Championship level, and that’s exactly where he intended to be for his third year of racing – a feat almost unheard of in the modern Grand Prix world. Having won his first race on the Suzuki at Mallory Park, Sheene became so dominant on it in Britain that year that he later left it at home and raced the Bultaco instead. It appeared to be an extremely sporting gesture but was, in essence, more of a shrewd financial move: the Suzuki was much too precious to risk in British rounds when it wasn’t needed, and Barry couldn’t afford to be faced with astronomical spares bills should he crash the bike or damage it in any way. The Suzuki was, however, the weapon of choice for the last Grand Prix of the season in Spain, which also happened to be Barry’s first. He had already wrapped up the 1970 125cc British Championship for his first-ever title and decided he needed to up the stakes as far as the competition went if he was to continue on his steep learning curve.

John Cooper remembered watching – sometimes from trackside, sometimes on the track – as the young Sheene progressed. ‘Initially Barry was like everyone else. He came up through the ranks in 125s and 250s, but he was always a good rider. At one point I had a 250cc Yamsel [a Yamaha engine in a Seeley frame] and he had a 250 and 350cc Yamaha so we often raced each other and he used to say to me, “I wish you’d bloody pack up and give me a chance.”’ Sheene didn’t get his chance until 1973 when Cooper retired after almost 20 years of racing. ‘Barry’s career just overlapped mine. When I finished racing he became really good. But he did ride my Yamsel a few times in the early seventies if I wasn’t using it just because it was a particularly good bike. He couldn’t beat me when I was on it really because his bikes were fairly standard at the time, but then he got the works Suzuki 500 and by then I had packed up and Barry just went from strength to strength.’

One week before that Spanish Grand Prix, Barry entered a big Spanish International event and actually managed to beat the current World Championship leader, the Spaniard Angel Nieto, to the great displeasure of the partisan crowd. It’s worth noting that big one-off international race meetings for bikes have now all but disappeared, but in the seventies there were many big-money meets which attracted all the best riders, and a win in one of those was equivalent to a Grand Prix win by virtue of the fact that all the GP competitors were entered in the race. They were also financially profitable, as Sheene explained in the 1975 Motor Cycle News annual. ‘At a Grand Prix, I could make between £200 and £500 for one start, but at a non-championship meeting in France, say, I could ask for over £2,000 – and get it.’ The risk of injury in non-world championship events eventually heralded their demise in the eighties; for sponsors, manufacturers, riders and teams, the World Championship had to come first and they actively discouraged their contracted riders from taking part in any other events.

Sheene’s Spanish win was just what he needed before making his Grand Prix debut, and only a small misjudgement in the setting up of his bike robbed him of the chance of winning that race too. He had been only half a second slower than Nieto in practice despite never having ridden the Montjuich Park circuit before, but his bike was slightly undergeared and Nieto won by eight seconds, with Barry a huge 40 seconds ahead of the third-placed rider Bo Jansson. It was a sensational debut, and also the start of a great friendship between Sheene and Nieto, who would play a big part in helping Barry learn Spanish. He later learned to speak Italian and French as well, to varying levels of fluency, allowing him both to read what was written about him in the bike press of those countries and to conduct interviews with their media – always a popularity booster when very few Brits bothered to learn a second language. Sheene’s Japanese was not as good, but it too proved invaluable over the years when dealing with his Japanese employers Suzuki and Yamaha and their respective mechanics.

Sheene also had his first ride in the premier 500cc class at the Spanish Grand Prix that weekend, although his debut cannot be taken too seriously. Up against the mighty 500cc MV Agustas, Barry pitched his little (albeit overbored) 280cc Bultaco just for a bit of fun. Even so, he managed to work his way into second place in the race before the Bultaco seized, putting an end to his efforts. Barry’s first ride on a real 500cc bike came at Snetterton that same year when he raced a crash-damaged Suzuki 500 his father had pieced back together. For once, though, Barry didn’t have superior machinery, and it showed as he failed to set the world on fire and eventually retired from the race, but it was a start, and it marked the first time he’d ridden the kind of bike that would make him world famous.

With 1970 delivering the 125cc British Championship, a third place in the 250cc British series and a podium finish in his first Grand Prix, it was decided that nothing less than a full-on assault on the World Championship would suffice in 1971. The amount of travel and mechanical preparation required for such an effort necessitated Barry quitting all his little odd-jobs. From that point on, for better or worse, he would have to survive on whatever start money he could negotiate and whatever prize money he could win. He would be racing for survival.

Motorcycle Grand Prix racing today is a world of glamour and big money: multi-million-pound transporters and hospitality suites, worldwide television coverage, hosts of glamour girls pouting and posing their way through the paddock, luxury motorhomes for the riders to relax in and even more luxurious pay cheques with which to buy them. But in 1971 it couldn’t have been more different, especially for a newcomer like the 20-year-old Barry Sheene. Sheene himself would later play a leading role in adding such glamour to international paddocks, but his first full season was, as for most racers, a rough and ready, hand-to-mouth experience. There were no first-class flights to the far-off rounds; instead, Sheene and his mechanic Don Mackay took turns to drive Sheene’s newly acquired Ford Transit around Europe. Luxury hotels and restaurants were still some way off too, so the van doubled up as accommodation and kitchen – at least it did when there was something to cook, which for most of the time there wasn’t. Don was paid a wage as and when Sheene won any prize money, and a meal in a restaurant was a rare treat if the team had done particularly well. Sheene might have been the source of some envy in UK paddocks when he turned up with ultra-competitive bikes, but when it came to Grand Prix racing he was no more privileged than any other privateer.

Money was so tight at times that desperate and innovative measures were called for just to keep the show on the road. Sheene recalled a time when he had to ‘borrow’ some red diesel from a cement mixer in West Germany so that he could make it to Austria. When he got there, he asked the race organizer to up his starting fee from £30 a race because he needed money for food for the coming weeks. When the organizer refused on the grounds that no one knew who Barry Sheene was, Sheene offered a unique solution: if he could qualify in the top three in each of his three classes, he would be paid £50 each time; if he couldn’t, he would be paid only £20. The organizer, thinking he could save some cash, agreed, but he’d seriously underestimated Barry’s talents. Sheene got his £150.

Financial hardship aside, the year went remarkably well, Barry scoring a third place on the 125cc Suzuki at the first Grand Prix in Austria. He was also on the pace in the 250 and 350cc classes, but mechanical gremlins robbed him of any more finishes, as they did in West Germany, too. A look at the results sheets of Sheene or any other rider from that era will show just how many mechanical breakdowns a rider typically suffered in a season. To a modern-day GP enthusiast this will seem inexcusable; after all, aren’t top Grand Prix mechanics paid handsomely to prevent just such occurrences? Breakdowns are now so rare as to be a real talking point among paddock pundits and the press, but in the seventies they were still commonplace. Reliability has improved massively in the three decades since Sheene first hit the Grand Prix trail, and the money now being thrown at teams allows them to replace parts much more regularly, further lessening the chances of any technological mishaps. While Sheene might have suffered an apparently high number of mechanical hiccups, other riders did so too, so it all balanced out over the course of a season. The old points system, where riders could drop an allocated number of their worst results, further helped to create an even playing field.

The potential dangers of mechanical problems increased considerably when the GP circus travelled to the unforgiving public-roads course that was the Isle of Man TT, Britain’s round of the World Championship at the time, and a place Sheene learned very quickly to hate. The TT had started in 1907, and Barry had enjoyed the meet as a young spectator and paddock helper. Riding it, though, was a different matter altogether. The course is unique in that it is 37.74 miles long and lined with walls, houses, lamp-posts and every other hazard you’d expect to find on normal rural and urban public roads. Grand Prix circuits in the seventies were still nowhere near as safe as they are now, but they were a lot safer than the TT course, if only because they were shorter and easier to learn. In 1971, Sheene decided to race on the Isle of Man to try to score some valuable points for his world title campaign. It was a move that would define Sheene’s views on the event and make him many enemies among traditionalists who continued to support the TT despite its perils.

Those traditionalists have always scoffed at the fact that Sheene crashed out of his first race there, but he’d actually been on the leaderboard before the incident. He posted the third fastest time in practice on his 125cc Suzuki and was leading the race at one point on the opening lap until he hit thick fog and eased off the throttle. When his overworked clutch bit too hard just after the start of the second lap, Sheene was tossed from his bike at the slow, first-gear Quarterbridge corner and his race was run – much to Barry’s relief, as he’d been hating every minute of it. But that wasn’t quite the end of Sheene’s TT career: he still had an outing in the production event on a 250cc Suzuki. Again, he posted respectable times in practice, but after suffering a massive tankslapper (or ‘speed wobble’, as it was more quaintly referred to at the time), during which the front end of the bike shakes viciously from side to side, parts of his machine started to work themselves loose and Barry pulled in after just one lap. He never raced on the Island again.

A rider’s decision not to race at the TT would never normally cause any kind of commotion; it is a free world after all, and no one forces racers to take part in the TT. But Sheene wasn’t content just to stay away from the island. Over the next few years he embarked upon a sustained one-man attack on the event and played a major role in the TT eventually being stripped of its World Championship status – a crime for which some have never forgiven him.

Racing fanatics fall into one of two camps over the whole Sheene/TT issue: if you love the TT, you hate Barry Sheene, and if you hate the TT, you tend to agree with Sheene’s actions. Barry’s major bone of contention was that riders shouldn’t be asked to race on such a dangerous track just to gain championship points. He never wanted the TT to be banned as such, he just wanted riders to have the choice of whether or not to race there, his thinking being that when valuable points are at stake riders may be tempted to push their luck to earn a few. TT supporters claimed that the throttle works both ways and riders can take things as easy as they want to, thereby reducing the dangers. Many supporters of the event have said that Barry was just too scared to race there, or that he couldn’t be bothered to spend the usual three years to learn the course well enough to win on it. The second argument falls down when you consider that Sheene was leading his first race there before he crashed, and Barry himself responded to the first accusation: ‘The Mountain [TT] circuit did not frighten me in any way. No circuit frightens me. I just couldn’t see the sense of riding around in the pissing rain completely on your own against a clock. It wasn’t racing to my mind.’

Don Morley, a professional photographer and journalist since 1955 and one of the most respected photographers in the business, has a different take on Sheene’s aversion to the TT. Morley has probably taken more pictures of Sheene than anyone else and was always privy to the gossip and chatter in the paddocks of the racing world. ‘Barry made a bit of a name for himself slagging off the TT, but it was more to do with money than the dangers of the place,’ he said. ‘A normal Grand Prix lasted three days whereas the TT was a two-week event and it cost the riders an awful lot of money to compete there. There was very little prize money and it was awkward for the GP riders to get to the Isle of Man from the Continent. They had to drive to a port, get a ferry to England, drive again and then get another ferry to the Isle of Man which was a lot more difficult than just driving from the Spanish GP to the French GP, for example. Then they had to pay for a hotel for two weeks instead of just three days as well as all the other expenses. It was good for the organizers, but not the riders. This was in the days before lots of long-haul Grands Prix, and it just didn’t make financial sense.’

In 1972 Giacomo Agostini, who won 10 TTs and 15 World Championship titles, joined Barry’s protest after his close friend Gilberto Parlotti was killed on his TT debut. Ago said he would never race there again, and he kept his word. He was joined by Phil Read, though five years later he changed his mind and did race there again. The event was finally struck from the Grand Prix calendar after 1976, much to Sheene’s approval.

Sheene’s name was dragged up in the press for more than a decade whenever there were calls for the TT to be banned outright, and to this day there is still a lot of resentment among TT fans towards him. But it’s worth remembering that while Sheene hated riding at the TT (‘Why bother when it’s so much easier just to shoot yourself and get it all over with?’), it didn’t stop him racing on other pure road cricuits, most notably Oliver’s Mount in Scarborough, a treacherous, narrow and bumpy parkland circuit. And many Grand Prix circuits such as Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium and Imatra in Finland were armco-lined pure road circuits too.

Certainly Sheene’s criticism of the TT circuit ran somewhat in contradiction to his view on these other dangerous circuits, a fact he attempted to explain in Leader of the Pack. In justifying his decision to continue racing at the Oliver’s Mount track, he said, ‘As with any other circuit, if there are sections which you can’t tackle with confidence, it’s up to you to ride through those sections at the pace best suited to you. You can make up for lost time in other stretches, where there is less likelihood of hurting yourself.’ Surely that same theory could apply to the TT circuit as well as any other?

Mick Grant, himself a seven-times TT winner and a staunch supporter of the event, was one of Barry’s fiercest rivals in the seventies. He testified to Sheene’s abilities on road circuits despite his aversion to the TT. ‘Although Barry knocked the TT, we never actually spoke about it together. My regret with Barry was that he didn’t continue with the TT. Certainly the way he rode on pure road circuits like Scarborough and Imatra, there was no way that he couldn’t have done the TT. I mean, bloomin’ hell, Scarborough requires all the road racing skills you’d ever need, and he could do it. He certainly wasn’t slow round there.’

Still, from 1971 the Isle of Man was out of his hair for good and Barry was free to concentrate on the next round of the World Championship, to which he travelled in a bit more style – in his newly purchased caravan. To the modern GP follower this will sound more like a club racer’s accommodation, but in 1971 it was the last word in luxury. For some, this was the start of Sheene the poser. Upstart relative newcomers to the GP scene were expected to sleep on the floors of their oily vans rather than tow a caravan around like a wealthy American tourist, but to Sheene it just made practical sense. With a more comfortable bed and an area for cooking some decent food, he would be in better shape for the racing. And if it added to his glamour-boy image and helped to improve standards in the paddock, then so much the better. One thing Sheene certainly wasn’t slow to notice was that having a caravan greatly increased his pulling power with the ladies, and for Barry that fact alone was worth the extra expenditure.

Motorcycle racing on the Continent was huge in the seventies despite the utter dearth of professionalism involved in its organization and the lack of money available to its star performers. More than 150,000 people turned up to watch Sheene being narrowly beaten by Angel Nieto at the Dutch TT in Assen, one of the best-attended rounds on the GP calendar. The next meeting in Belgium got off to a bad start when Sheene was fined for spilling fuel on the track. He had been returning from a night out and was driving down the circuit to get to the paddock when his van ran out of diesel. He managed to bleed the fuel system and top the van back up, but not before sloshing some diesel onto the course. A vigilant Belgian policeman witnessed the incident and Barry was fined the now comedic-sounding sum of £6.60. He also incurred the wrath of his fellow riders who had to negotiate the slippery section of the track. But if the weekend got off to a bad start, it ended in the best possible way with Sheene taking his first-ever Grand Prix victory in the 125cc race. It was made a little hollow by the fact that Nieto had retired on the third lap, but Barry didn’t care; a first win is always a watershed, and he couldn’t have been more delighted. As he recalled, ‘Once I had crossed the finishing line, I could hardly contain myself. I wanted to get drunk, kiss as many girls as I could lay my hands on and just dance with joy. That was the proudest moment of my life up to then.’

A second in the 125 and a sixth place in the 250 race on his Yamaha in the East German Grand Prix were followed by a second GP win, this time in the 50cc class in Czechoslovakia. Kreidler had approached Sheene at the Belgian GP about riding one of their factory bikes to help out their full-time rider, Jan de Vries. For Sheene it was a chance to add to his start and prize money with minimum hassle as the factory team would take care of the bike. Race day didn’t start too well: Barry overslept and was ‘peacefully dreaming about two blondes’ when he was rudely awakened by members of the Kreidler team hammering on his caravan door. Pulling on his leathers and wandering bleary-eyed to the starting grid, Sheene was in no mood to go racing. He’d much rather have been left with his imaginary girlfriends. ‘When [I] set off,’ he recalled, ‘I think I gave a huge yawn; I was still half asleep. But I buzzed round as quick as I could in the wet with my head thumping and my teeth chattering with cold.’ In fact he buzzed round quickly enough to win the race from Nieto, who was by now firmly established as his arch rival no matter what class he seemed to race in.

He was certainly the man Sheene needed to beat in the 125cc class if he was to become the youngest ever Grand Prix world champion, and when Nieto’s bike expired during the Swedish round it began to look likely that Barry might just pull off a shock title win from the Spaniard. When Nieto also retired from the Finnish Grand Prix, Sheene held a 19-point lead with just two rounds to go and was being touted as the champion elect. Unfortunately for Sheene, a non-championship event in Hengello, Holland, then all but ruined his chances: he crashed, breaking his wrist and chipping an ankle. It was Barry’s first bad accident, the first time he had broken a bone while racing, and it’s easy to see now why top Grand Prix riders no longer take part in non-championship events, with the exception of the Suzuka 8-Hour race in Japan which remains massively important to the Japanese manufacturers who call all the shots.

Strapped up and in considerable discomfort, Sheene rode to a highly creditable third place in Italy behind Gilberto Parlotti and Angel Nieto and refused to blame his injuries for his failure to win, saying instead that his bike was simply not fast enough on the day. He remained in the hunt for the title, but it was to be yet another non-title event, the prestigious Mallory Park Race of the Year, that really did put an end to his hopes. It seems incredible that Sheene, having had a warning with his crash in Holland, would contest another race and risk further injury so near to the final round of the World Championship, but it was the norm for the time as well as being the only way riders could make enough money to survive a season. This time Sheene was thrown into a banking when his rear tyre lost traction. He was taken to Leicester Royal Infirmary for a check-up but, despite being in great pain, was discharged after being told he hadn’t broken anything. It was an extremely poor diagnosis: Sheene had in fact broken five ribs and suffered compression fractures to three vertebrae.

Oblivious to the fact, he travelled to Spain to take on Nieto for the final showdown in the world title chase. After again racing the 50cc Kreidler, which broke down on the last lap, Barry stooped over a fountain in the paddock to have a drink of water. That’s when he heard the disconcerting and agonizing ‘ping’ as one of his broken ribs popped out of place and threatened to burst through his skin. Never one to shirk from pain, Barry forced the rib back into place and taped up his torso to hold the offending bone in place long enough to last the race. Just making it to the Jarama start grid was the first of many superhuman efforts shown by Barry Sheene in his pursuit of racing glory. He and Nieto had a fantastic scrap all race long and were heading into the final stages when Barry hit some oil and slid off the Suzuki, his race and World Championship hopes over. After all his painful efforts, he had lost his grip on a title which had been so close because of a patch of oil that should have been cleaned up anyway. The only consolation for Sheene was that he didn’t further aggravate his injuries in the crash.

It might have been a disappointing way to end what had been a great year, one that had delivered 38 race wins, but Sheene didn’t dwell on it for long. Having so nearly taken a world crown at his first attempt, he was confident he could definitely lift one the following year. For the 1972 season, he signed for Yamaha to ride its 250cc and 350cc machines in what was his first season with a factory team. At last he was being paid to go racing. The year started off well, and Sheene picked up his first-ever 500cc class win at the King of Brands meeting over Easter. But that only fuelled his confidence and added to the complacency with which he faced the Grands Prix. Things went wrong from the very first round when both Yamahas suffered mechanical breakdowns. The bikes were both slow and unreliable, and Barry didn’t help matters when he badly broke a collarbone during the Italian Grand Prix. The only highlights of the GP season were a third place in Spain and a fourth place in Austria, both in the 250cc class, and that was hardly a step up from the year before when he’d won four Grand Prix races. Sheene was acutely aware of the fact, too.

Such a disastrous season led to bad feelings between Sheene and his Yamaha team and he was desperate to leave by the end of the year to prove that it had been the bikes and not his riding at fault. These bad feelings would come back to haunt Barry years later when he once again rode a Yamaha. Those same lowly mechanics from the 1972 season had risen up the ranks to become senior personnel by 1980, and whenever he asked for a favour Sheene discovered that they had long memories. Had he kept his views on the 250 Yamaha to himself, or at least confined his criticism of the bike to behind closed doors, there would have been no problem. As it was, he made no secret of what he thought of the bike, and there is no surer way to offend the Japanese corporate psyche. Still, Sheene was prepared to shoulder some of the blame for his worst year to date: ‘That poor year in 1972 taught me a salutary lesson about the dangers of becoming big-headed. Over-confidence was the root of my problems.’

With Sheene’s reputation having taken a bit of a battering, he was really out to prove himself in 1973. He had a new contract with Suzuki and a new championship challenge beckoned: the FIM Formula 750 European Championship, in many ways the predecessor of the current World Superbike Championship. The Formula 750 Championship was, to all intents and purposes, a world championship even though it didn’t enjoy the prestige of being conferred with official world-class status. The calendar of dates was just as gruelling as the Grands Prix, and the calibre of riders almost as impressive.

The new breed of 750cc superbike racing had taken off in America in the early seventies and reports had reached Sheene that Suzuki’s new three-cylinder 750 had been clocked at 183mph in testing – allegedly the fastest speed ever attained by a race bike at that time. Sheene couldn’t wait to get his hands on one. Despite the fact that he had cut his teeth in 125 and 50cc racing, he now referred to the smaller-capacity bikes as being very ‘Mickey Mouse’ and was determined to prove he could win in the world’s largest-capacity racing class on what he considered ‘real men’s bikes’. Sheene duly got a Suzuki triple from the US where his brother-in-law, Paul Smart, would be racing one. Smart had been an arch rival of Sheene’s over the past few years but the pair had continued to have a friendly relationship. Barry had been as pleased as anyone when Paul tied the knot with his sister Maggie at the end of 1971, a marriage that still stands today and which produced current racer Scott Smart, Sheene’s nephew.

When Barry eventually took delivery of his new Suzuki it was immediately apparent to him that it was not the exotic piece of machinery he had been expecting. Much midnight oil was burned as he slotted the engine into a Seeley chassis and rebuilt the bike to a more competitive spec. In the end, his hard work paid off. Despite winning only one round of the eight-round championship, Sheene’s two second places, a third and a fourth meant he accumulated enough points to win the title ahead of Australian Jack Findlay, John Dodds and his own team-mate Stan Woods. Of the remaining rounds, he had two non-finishes and was disqualified from the British round at Silverstone for switching bikes between the two race legs. It was Sheene’s most prestigious championship win to date, and he proved that he really had mastered larger-capacity machines by adding the Motor Cycle News Superbike title, Shellsport 500 title and King of Brands crown to his collection.

Sheene was now really starting to make a name for himself, not only as a racer but as a great PR man and a bit of a grafter, as John Cooper explained: ‘Barry was always a very determined chap. He worked on his bikes a lot and they were always nicely prepared and presented. He used to try hard and he was very professional. Preparation is the thing with bikes, and he was always keen, fiddling about, changing the sprockets, altering the forks and the springs – not like today when riders just come in the paddock and dump their bikes on their mechanics. He wasn’t shy of grafting. Years later I used to go down to his house when he lived at Charlwood and all his spanners were laid out neatly in his workshop and his helicopter sat there all nice and clean. He was very organized.’ Cooper, like Chas Mortimer, had known Sheene long before he started racing and was happy to help Frank’s boy in any way he could. ‘We used to help each other out, lending each other bikes and stuff; you know, we were just friends really. But he didn’t need much steering because he always had the makings of being the right man for the job, and that was apparent even in the early days.’

After such a disappointing year in 1972, Sheene was most definitely back. Readers of MCN recognized his achievements by voting him their Man of the Year for the first of five times in his career – a record that stood for almost two decades until Carl Fogarty accepted the award for a sixth time in 1999. Moreover, Sheene’s F750 victory was enough to convince Suzuki that he deserved a ride on their all-new RG500. The four-cylinder, 500cc Grand Prix weapon was to become a racing legend in its own right, winning four world titles between 1976 and 1982, but in those early days it was an absolute beast to ride, all power and no handling. When Sheene first tested the bike in Japan at the end of 1973, he found, like everyone else who had ridden it, that the bike had a nasty habit of weaving viciously at speed and pulling wheelies under power, but it was still the fastest bike he’d ever ridden and he proved it by knocking one and a half seconds off the Ryuyo track record in tests.

The plan for 1974 was not only to defend his Formula 750 title but, more importantly, to contest every round of the ultimate motorcycle series – the 500cc Grand Prix World Championship. It would be Sheene’s first ever year in the premier class and he knew the RG500 was up to winning races once the handling was sorted out. But that was easier said than done, and 1974 was to prove a tough baptism for Sheene. The gremlins in the RG’s handling were never truly rooted out that season, and the bike was further plagued by mechanical faults, as most new machines are. Gearboxes and drive shafts were particularly prone to breaking, and Barry had his fair share of crashes, which only added to his problems.

The first outing for the bike was in March at the Daytona 200 race in Florida. It was Barry’s first time there as well as the Suzuki’s, and that meeting inadvertently led to Sheene adopting the now famous number seven. As he told me during an interview for Two Wheels Only magazine, ‘Seven was always my favourite number even as a kid. I’d want seven this or seven that. Then, when I went to Daytona in 1974, I asked what numbers were available. The Americans usually give new riders really high numbers, but Mert Lawill had retired so seven was available. I was well chuffed.’ The lucky number seven wasn’t the only thing Sheene took away from the States. He also latched on to the American habit of displaying the number for all to see while brightening up his racing attire, too. ‘The Americans made you wear your number on your helmet and leathers too, which was even better, and I kept the look when I got back to Europe afterwards.’

It was just as well that Barry brought something away from Daytona because ignition trouble ruined his chances of getting a result in the race. After that, a fine second place in the first Grand Prix of the year proved to be a false indicator of what to expect. Along with most of the other riders, Sheene sat out the German race in protest at the lack of straw bales surrounding the course, then finished third in Austria after suffering the humiliation of being lapped by Giacomo Agostini and Gianfranco Bonera. Four consecutive non-finishes followed for the fast but fickle Suzuki, and a fourth place in the final Czech round was little consolation for a bitterly disappointing 500cc GP debut season in which Sheene had managed to finish only sixth overall. The defence of his Formula 750 title had been a bit of a wash-out too; Barry hadn’t really had time to concentrate on that series as well as the Grands Prix and had had to give second best to the new, super-fast Yamahas. There were brighter moments, though, like scoring the RG500’s debut win at the British Grand Prix, even though it was a non-championship event and as such shouldn’t really have been called a Grand Prix at all. Barry also won the Mallory Park Race of the Year as well as the Motor Cycle News Superbike Championship and the Shell Oils 500 title, salvaging some home pride after a difficult year.

Suzuki were extremely disheartened, though, and ready to throw in the towel with the RG500 project until Sheene insisted on spending five gruelling weeks in Japan working on the bike to turn it into a winner. By the time he was through, Sheene was convinced he could challenge for the 1975 World Championship. But first there was the Daytona 200 to think about, and this time it would make him an international superstar – for all the wrong reasons.